Do the Right Thing: Identities as Citizenship in U.S. Orthodox Christianity and Greek America

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

Abstract

In this work, I bring attention to recent initiatives that call upon U.S. Christian Orthodox and Greek Americans to express citizenship as anti-racist practice. I historicize these initiatives tracing their links with the legacy of mid-twentieth-century Civil Rights, and I discuss how the civic activism of these groups draws upon their specific religious principles and cultural ideals, respectively. These narratives of citizenship obviously differ on the grounds they rationalize their call for political activism, the Orthodox centering their commitment to civil rights on the theological principle of deification, the Greek Americans on secular Greek cultural values. Both the religious and the ethnic narrative share the recognition of the United States as non–color blind. And both posit the practice of citizenship, understood as interracial advocacy for civil rights, as an integral component of their respective Orthodox Christian and Greek American identities. In other words, they approach identity as a civic obligation. They see cultural and religious identities as a position that is achieved via practices of citizenship. But how effective is it to place premium significance on values as an engine for social change? I reflect on the political efficacy of these narratives, identifying how and why they might be challenged by their own constituencies, Orthodox and Greek American, that they seek to reach.

What is the relationship today between European Americans and citizenship? To what extent do ethnic groups such as Irish Americans, Polish Americans, or Italian Americans each mobilize collectively, for instance, to advocate civil rights and oppose racial discrimination or xenophobia? One might raise the same set of questions in relation to members of religious groups associated with European Americans–such as U.S. Catholicism and Orthodox Christianity. Do they engage with issues of social injustice, and if so in what manner? These questions are particularly apt to ask in the era of Black Lives Matter, immigration “zero tolerance” policies mandating the separation of children from their parent(s), and emboldened white nationalism. Since the American government officially sanctioned the ideology of multiculturalism in American society, in the 1960s, European Americans have largely privileged depoliticized aspects of their expressive culture such as cuisine and dance in public displays of their identities. Parallel to their festivals and parades, however, they also became active in diaspora politics, seeking to shape American foreign policy on behalf of their historical homelands. And to some extent many became active, as American ethnics or members of particular religious groups, in openly confronting civic and political issues in American society. This latter activism has been lately intensifying, and is particularly visible. A significant demographic among Irish Americans for instance, publicly mobilized as Irish Americans to oppose the current administration’s immigration policies, with sectors of Italian Americans supporting the Irish initiative. The questions I raise therefore speak to a wider phenomenon of European American politicization: how is the connection between ethnicity and citizenship expressed? Under what circumstances do, and can, European Americans politicize their ethnic identities? In what ways is religion linked with citizenship today?

I take up these questions in reference to U.S. Orthodox Christians and Greek Americans in particular. I identify religious and national initiatives in which these demographics express solidarity, in words and social practice, with African Americans, joining forces in the interest of combating racial discrimination and overall safeguarding equal civil rights for all. I historicize these initiatives tracing their links with the legacy of mid-twentieth-century Civil Rights, and I discuss how the civic activism of these groups draws upon their specific religious principles and cultural ideals, respectively. Of significance is that intellectuals representing Orthodox thought and Greek American cultural leaders advocate secular education about the experience of African Americans as pivotal in the forging of interracial bonding. The understanding of the African American predicament is seen as a civic responsibility for Orthodox Christians and Greek Americans, and consequently, education is proposed as a route to motivate and materialize engaged citizenship.

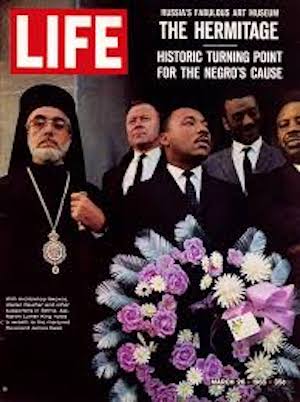

My departure point is the value these initiatives assign to an emblematic religious leader who was directly connected with Civil Rights era activism, namely the late Archbishop Iakovos (1911-2005), Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America (1959–1996). The relevance of this figure rests in his vocal advocacy for the rights of disenfranchised African Americans, and his public participation, bold at the time, in their struggle for equal civil rights. This political involvement commanded major national attention at the time, when Life Magazine published, in March 26, 1965, the now iconic image of Iakovos marching alongside Reverend Martin Luther King in Selma, Alabama. The photograph of the two leaders joining in defiant unison captured a historical moment of multilayered solidarity, an intersection of interests that coalesced across denominational, cultural, and racial differences. This was all the more significant at a time when interracial alliances were met with deadly force, particularly in the American South.

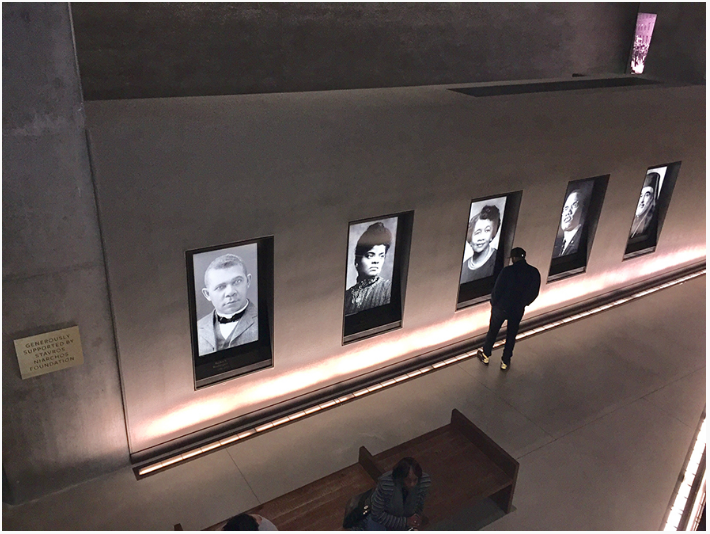

Iakovos has been celebrated as a religious and civic leader who was vested in turning U.S. political ideals into reality at a time of acute conflict over the direction of the nation. He was committed in turning principles, expressed in words, into actual deeds performed in public. This activism has earned him ample national recognition. President Jimmy Carter bestowed upon him The Presidential Medal of Freedom. In his honor, the city council of Astoria, New York, gave the neighborhood’s 33rd Street the honorific co-name of “Archbishop Iakovos of America Way.” The African American community holds him in high esteem too, as testified by Iakovos’s eminent place in the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a major institution inaugurated in 2016. The dedication of a special reflection area named after him brings distinction to this pioneer, as it encourages visitors to contemplate the meaning of civic involvement. Iakovos, the symbol of a most important interracial coalition, is institutionalized and, once again, brought to the center of attention for contemporary contemplation about the moral and political fabric of the nation.

At stake in this commemoration is citizenship as an activity that aims to

shape the ideas, values, rules, and policies through which a polity governs

itself. This notion of citizenship extends beyond conventional

understandings of citizenship as legal status and its associated duties

such as voting. It includes responsible understanding of social issues, the

willingness to engage in informed dialogue across cultural differences, as

well as civic participation to condemn and correct practices that harm

specific populations. In this respect, Iakovos exemplifies the ideal of

citizen as activist—marching to protest injustices, writing letters to high

ranking U.S. politicians to influence policy, issuing encyclicals to his

congregation—in support of a movement that sought to transform both laws

and social views that devalued an oppressed demographic, African Americans.

The example of Iakovos’s practices of citizenship in the past circulates

across the public sphere with increasing frequency, in fact urgency, as I

will show, in the present.

What motivates this development? The changing contours of the political landscape in the United States offers an answer to this multifaceted issue. First, the rise of white nationalism renders racism hypervisible in the public sphere, and in turn emboldens racist behavior both in institutional fora and everyday life. Everyday microaggressions and deadly violence are captured on camera, making the nation witnesses to the everyday behavior of individuals hurling racial insults to nonwhite people; unwarranted police killings of black people shock a sector of the nation. I write at a time when misinformation and disinformation obstruct informed understanding of fundamental issues of civil rights in the country. Despite well-reasoned arguments that establish racial discrimination in the country as pervasive and operating in institutions as well, a significant sector in the society subscribes to the notion of racial discrimination as an exception, performed by deviant individuals. It is not seen as a social problem but an individual’s problem. In fact, the power of opposition to well-reasoned scholarship illustrating African American grievances is such that it may dishearten and even paralyze well-meaning academics who might find combatting racism to be an insurmountable task. Hence educators mobilize for empowerment, animating the model of the educator-citizen who insists on speaking about the value of engaged citizenship. “Don’t Retreat,” they write, “Teach Citizenship.”1

I place my work within this political and pedagogical landscape. Fostering the conversation about citizenship in an era where racial tensions, even animosities, intensify is not a choice but a necessary practice of scholarship as citizenship. Equally urgent is the question of readership. Writing about citizenship cannot be divorced from the aspiration to reach the widest possible audience, including undergraduate college students, for the classroom is a vital place to cultivate the consciousness and skills that responsible civic participation requires. I make it my task, then, to identify an unfolding discourse among U.S. Orthodox Christians, and Greek Americans entering into an alliance with African Americans around shared practices of citizenship. This is to initiate a discussion. I am new to citizenship studies, and my analysis is not as theoretically multifaceted as I would have liked it to be. My foray into this field is mostly guided by the urgency for the field of Greek American studies to start engaging with important developments regarding identity and citizenship. I make a conscious effort to communicate my work in a manner that is readable to nonacademics within the overall aim to advance civic education via public scholarship.

I identify two narratives advocating solidarity with African Americans, one religious, that of U.S. Orthodox Christians, and one secular, that of Greek Americans. These narratives obviously differ on the grounds they rationalize this aim, the Orthodox centering their commitment to civil rights on the theological principle of deification, the Greek Americans on secular Greek cultural values. Both narratives share the recognition of the United States as non–color blind. And both posit the practice of citizenship, understood as interracial advocacy for civil rights, as an integral component of their respective Orthodox Christian and Greek American identities. In other words, they approach identity as a civic obligation. They see cultural and religious identities as a position that is achieved via practices of citizenship. But how effective is it to place premium significance on values as an engine for social change? I reflect on the political efficacy of these narratives, identifying how and why they might be challenged by their own constituencies, Orthodox and Greek American, that they seek to reach.

Theosis and the Politics of Empathy

Orthodox theology opposes racial discrimination on the principle of theosis, or deification. Theosis calls upon humans to strive to become Godlike, the aspiration, that is, to achieve the ability “to love as God loves.” Universal love for humanity is fundamentally antithetical to hatred of any kind. But learning how to attain genuine love for Others, including enemies and strangers, is not an easy task. “On the surface,” Aristotle Papanikolaou, the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture, writes, “it would seem that, of course, Christians are against racism—we should never think someone is inferior because of race.” But achieving theosis is not merely a personal issue, but a political matter too:

[T]heosis calls us to a deeper level. The struggle to learn how to love is one that includes rooting out racism in our own hearts and in the very structures that constitute the political, cultural, and economic matrix within which we locate ourselves. The first requires incessant self-reflection; the second requires action.2

This position interweaves a secular dimension in the spiritual quest for theosis: it acknowledges the power of society to shape the individual Self. In turn, it unequivocally recognizes the existence of structures of racial discrimination, which, further, may infiltrate the psyche of Orthodox Christians. A genuine Orthodox life, therefore, requires both self-reflection and political action. It places the responsibility upon the individual to remake the Self and simultaneously battle those structures of racial discrimination that may percolate the Self. The U.S. Orthodox narrative, then, incorporates a commitment to civil rights, the rights of African American and other people of color in the United States, to its ecumenical tradition of protecting human rights everywhere. In this interconnection of universal inclusion and respect for all human beings with civic activism for social transformation, it follows the example of Iakovos.3

The ecumenicity of Orthodoxy, the centrality of Christian love, the necessity of interfaith dialogue across racial lines, and the imperative of a Church active in advocating human and civil rights were the key principles guiding the policies and politics of Iakovos’s engagement with the question of race in the United States during the civil rights movement. The Archbishop primarily legitimized his actions on the basis of Christian universal values, as it was expected by a religious leader. Citing his faith’s ideals of human equality, love, and empathy for the disenfranchised, he duly noted that injustices such as legal barriers to voter registration, racial segregation, and pervasive racism not only deprived African Americans of their fundamental political rights, but dehumanized this population as well, thus linking civil and human rights as inseparable. Iakovos informed the nation and reminded his flock of the inclusive ecumenicity of Greek Orthodoxy to consequently legitimize desegregation on theological grounds and the international realities of an inclusive church. The church leadership promoted a staunch antisegregationist stance in public as early as the 1950s, and Iakovos unequivocally and consistently adhered to it throughout the turbulent 1960s. As Athanassios Grammenos notes:

From a philosophical standpoint, the Greek Orthodox tradition is ecumenical in the sense that it supports the unity of Christians throughout the world (oikouménē). … [A]ll people are considered equal, regardless of ethnicity or differences in religion and cultural background. Consequently, racial segregation is unthinkable for communities not only in the United States but also in any other place of the world. The spirit of this attitude was clearly stated by Arthur Dore, Director of Public Relations of the Archdiocese, [who asserted in 1958] that his Church “has always been democratic without prejudice in reference to race or color, adding that it would be a paradox to discriminate communicants of color in the U.S. while in other countries, such as Liberia and Abyssinia, a majority of the members are dark skinned.”4

It was a moral imperative for Greek Orthodoxy not merely to express its rhetorical condemnation of racial inequality in words, but also to act out and practice its interracial solidarity. The church, Iakovos stressed, “could no longer remain a ‘spectator and listener,’ and it must labor and struggle to develop its spiritual life.”5 Seeking to align the ideal with the real, the Archbishop turned spiritual obligation into a programmatic civic engagement for transforming the political and cultural life of the nation. Iakovos animated the power of Orthodox religious and moral principles in positioning his church at the forefront of civil rights struggles during a turbulent era.

All these elements are present in contemporary Greek Orthodox conversations about civil rights, a testament of Iakovos’s enduring legacy. PRAXIS, a publication of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese, dedicated an issue to Iakovos’s memory in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of his activism in Selma. Tellingly, the issue prominently features the Archbishop’s farewell remarks upon his retirement at the Grand Banquet, Clergy–Laity Congress, July 3, 1996, a leader’s statement offering a moral and political compass for the Church:

We, in the Americas, … will continue to grow in the truth and beauty of the Christian spirit, as truly ecumenically minded, being concerned and committed to peace with all religions and to the eradication of bigotry, discrimination, injustice, violence and racial hatred.

The march in Selma, Alabama, will continue to pave the way from which we shall never deviate along with the frontiers of unity and social justice. Ours is a commitment to true Christianity, to true justice, to the liberation of people still oppressed, and to true peace, the one founded upon respect of life and of each other, as we declare in our Pledge of Allegiance.6

According to †Metropolitan Nicholas of Detroit, Iakovos “became the standard against which we [the Church] would even measure our own actions.”7

The same set of principles also reanimate broader Orthodoxy, guiding its activism in a historical moment when hard-won civil battles are under threat. For organic intellectuals committed to turn Orthodox Christian ideals into practice, the aim to maintain, even restore, an Orthodox ethos of citizenship on the issue of race among the faithful, and the plea for political engagement toward this goal, is central. Finding a hospitable forum in Public Orthodoxy, an online publication that fosters critical conversation about Orthodox issues, scholars advocate deification, as I have mentioned, as the moral route to combat beliefs and ideas that unjustly work against African American interests. The question of race in the United States is of course fundamentally different than it was fifty years ago, when legal barriers assigned African Americans to second-class citizens. The challenge today is not merely to fight openly racist positions, increasingly visible in the public sphere, but to name how certain laudable, highly valued national ideas and beliefs obscure the actual realities of people of color in the country.

To correct this misrecognition, Orthodox scholars assert that both the operation of institutional racism and the existence of widespread racial discrimination in the past as well as in the present justify African American economic and social grievances. Orthodox thinkers appear aware that their key claim, the operation of institutional racism, is controversial, often denied by those who adhere to the notion of the United States as a fundamentally color blind society. The basic premise of the necessity of rooting out racism as a route to genuine Orthodoxy requires therefore to identify both specifically where and how racism operates, as well as its consequences. Editorials in Public Orthodoxy indeed regularly cite academic research and case studies that are widely discussed in the public sphere to demonstrate how racism inflicts multiple facets of Black America. Commentators do not shy away from explicit political references, linking institutional racism with white nationalism and mainstream political rhetoric. For these thinkers, the current political landscape is a cause for alarm:

This illusion of progress has unraveled at the seams in the past year and a half. The Black Lives Matter movement shed light on police brutality against the African-American community, Michelle Alexander’s brilliant book, The New Jim Crow Law, revealed disturbing racial trends regarding who gets incarcerated and for how long, and Donald Trump won the American presidential election with a campaign that attracted the support of the KKK. All the while, race-based hate crimes have risen in the past year.8

The Orthodox project of theosis links its spiritual aspiration with secular knowledge. It assigns Christians the civic obligation of understanding the contemporary and historical predicament of African Americans. Orthodox-affiliated scholars ask that the public critically examine its assumptions about African American lives and political movements, inviting in turn, informed dialogue across difference. They draw upon contemporary conversations regarding white privilege in order to render visible the ways in which discrimination is performed in everyday life and to raise consciousness about poverty and marginalization as a result of a discrimination, not cultural predispositions:

What our struggle for theosis most demands is a politics of empathy. What can this look like? … In imagining what it is like to be in the body of a Black person in the USA, perhaps we can see more clearly the structures in place that facilitate the inequality among persons. Those Orthodox Christians who say that Blacks should just “improve their culture” (yes—I’ve heard this), do not have a sufficiently theological understanding of sin and its insidious and lingering social effects. Is it really that easy, as an example, to will a better life for those who find themselves judged unemployable for a job or unworthy of a promotion because of their skin color–much as some Orthodox Christians in a not so distant past?9

The route to theosis passes through the road to citizenship. The latter is seen as more than adhering to legal rights associated with citizenship such as voting. Citizenship entails the ability of a person to engage in meaningful dialogue with others, as well as to exhibit empathy, the capacity to identify compassionately with the experience of others. Both these abilities are acquired personal skills that may be “less overtly political,” yet “more than a soft-hearted view of citizenship as mere affect.” The making of citizens through education interweaves the personal and the political. Active involvement on behalf of a collective hinges upon a person’s capacity to experience a sense of empathy, develop “ethical consciousness, and capacity to engage in dialogue with others.”10 Papanikolaou questions erroneous assumptions about the Other, namely the widespread misconception linking poverty among African Americans with their culture. In this respect, he points to the foremost mission of educating American citizens. As James Banks, one of the founders of multicultural education, writes, “[t]o become effective citizens in the twentieth-first century students must be knowledgeable about the conceptions of various ethnic and racial groups within society, how these conceptions were constructed, and their basic assumptions and purposes.”11

Orthodox scholars embrace the common definition of empathy as “identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings, [and] motives” coupled with the capacity for compassion toward that person’s position.12 Specifically, Orthodox people and Greek Americans are called to put themselves in the place of an African American person; to move beyond comfortable whiteness, that is, and imagine “what it is like to be in the body of a Black person in the USA.” They are invited to imagine how it feel to embody “blackness” in a society where black bodies are often seen as dangerous, unworthy, or unemployable.13 There is a twofold interest here. Education, in this narrative, offers the means for understanding the predicament of African Americans, of learning something one lacks from direct experience. And there is the call to set in motion one’s imagination to feel how it would feel if we were in the position of the Other, an imaginative bridging across difference that is necessary to generate compassionate identification.

The Orthodox call for action links empathy for the Other with education about the Other. In fact, it relies on those possessing the above skills to mobilize others: “educating parishioners, mobilizing a parish, political involvement, participating in and facilitating racism training, to name simply a few.” Knowledge empowers Orthodox persons “ultimately to non-demonizing action [black lives matter] that attempts to transform the structural matrix that facilitates treating all persons as being made in God’s image.”14

Not mincing their words, Orthodox scholars build on their church’s history of solidarity activism to critique the government and disrupt the community’s complacency on the issue of race: “Overcompensation, especially during Trump’s presidency, may mean getting out of our comfort zones and opening up dialogues with ourselves and others.” Drawing from the example of Iakovos, they call for institutional action: “The Orthodox Church should not shy away from the task ahead: embracing and representing more of those who are not of the typical Orthodox demographic, as well as marching, like Archbishop Iakovos, in solidarity.”15 U.S. Orthodoxy embraces the twofold legacy of the Orthodox citizen who speaks up and acts up. Scholars boldly practice the former, and high-ranking clergy acknowledge, as I will point out, the issue. Will the institution and the faithful follow suit regarding activism?

Hellenism and Citizenship: Secular Solidarities

Secular activism seeks to mobilize civic activism among Greek Americans. On March 27, 2013, at an event celebrating Black History month, an assembly of more than 60 individuals came together at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History, in Baltimore, Maryland. The purpose was to affirm and formalize a civic bond between Greek Americans and African Americans. Organized by the Johns Hopkins Hellenic Student Association in collaboration with the Black Student Union, the event carried major import, given the ample attendance of political and cultural leaders both at a national and regional level. Speakers included Baltimore’s Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, Deputy Mayor Kaliope Parthemos, Congressman Elijah Cummings (D–MD), Congressman John Sarbanes (D-MD), Senator Paul Sarbanes (D-MD) as well as University presidents and deans, among others. Business executives, attorneys, policy makers and students were in attendance too. Befitting its purpose, the event commenced with a short film paying tribute to Archbishop Iakovos and was interspersed with speeches by the dignitaries who posited the respect of the dignity of every individual and the responsibility toward the common good as the shared values connecting Greek Americans and African Americans.16 It concluded with a proclamation by Anthony Brown, Maryland’s Lieutenant Governor at the time, “whereas the American Hellenic Progressive Association (AHEPA) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) have partnered to combat modern day bigotry,” designating March 27, 2013 “as a day of celebration in honor of the unity of the Greek American and African American communities.”17

This alliance represents one response to the call of a wider civic project, namely the Sarbanes–Hellenism in the Public Service initiative. Established in 2010 by Congressman John Sarbanes, this represents an initiative, which, as its title indicates, brings together two key terms, Hellenism and public service. It invites Greek Americans to start or to continue contributing to society as leaders or volunteers—fundraising for a school, serving in the board of a hospital or a museum—to enhance public life. “Giving back to the broader community” is seen as an integral part of Greek American heritage that must be cultivated.18

In this respect, Hellenism, a concept variously defined,19 is identified in this narrative in relation to civic engagement. The Sarbanes version proposes that Greek identity finds expression through active participation in matters of the polity, including advocacy for civil rights. The initiative interfaces Hellenism with public involvement, an American cultural and political ideal, fostering in this manner an alignment between the cultural heritage of an ethnic group and the civic ideals associated with belonging to a national community.

It is of interest to reflect on the ways in which political and cultural elites craft the narrative of Greek American/African American solidarity. A common denominator is the recognition, both in the event itself as well as in commentary about it in the Greek American media, of a host of preexisting formal and informal African American and Greek American mutualities in the near and distant past. The narrative foregrounds these linkages to produce a history where Greek Americans and African Americans (but also Greeks and Africans) joined together to promote common causes and interests.

Speakers at the reception, for instance, acknowledged the multiple ways through which they have been personally involved in “Greek/African” American interconnections: they have participated in political alliances, collaborated in civic projects, and experienced mutual support and enduring friendships. The long-lasting friendship between the Baltimore mayor and deputy mayor, since high school, was featured prominently as yet another layer to their collaboration in local government. Undoubtedly, regional and national politics are at play here. References to the Greek American community’s support for the city’s African American mayor illustrates a wider political dynamic where the Greek/African bond could potentially work in the favor of the participating politicians.

A political elite then acts upon a multifaceted network of interests to forge a coalition across racial and cultural differences. Joining together is seen as a mechanism for greater political efficacy. Consequently, speeches at the March 27 assembly addressed ways to cultivate this bond and reach the goals that such a convergence aspires to achieve.

There was a tentativeness, admittedly, among the various speakers in identifying the specific aims of the alliance. The conversation is indeed in its infancy, noted the Greek American deputy mayor, who passionately advocated the necessity of mutual understanding as a tool to curb anti-immigrant and racist views among Greek American youth. The praise that senior politicians accorded to the civic-minded and perhaps politically aspiring young organizers of the event speaks to the significance of the event, and by extension of the Sarbanes–Hellenism in the Public Service initiative, as the means to nurture a new generation of Greek American leaders committed to civic inclusion. Hellenism in this rendering entails practices of citizenship that promote interracial solidarities to oppose racism and xenophobia.

The initiative for an African American/Greek American alliance rests on shared civic values. It certainly acknowledges cultural differences, but instead of seeing these differences as absolute boundaries, it approaches them as resources that facilitate the crossing of racial and cultural boundaries, clearing in this manner a common ground for mutual understanding and action. A Greek American speaker at the reception, Andreas Akaras, recognizes and endorses the value of a cross-cultural political collective:

There will always be calls to action voiced by great men like Dr. King, and it is hoped that there will always be men like Archbishop Iakovos willing to respond, for without reciprocity, one man’s greatness can only do so much. Perhaps it is said best by an African proverb Congressman Cummings had the insight to quote: “If you want to go fast, go by yourself. If you want to go far, go together” [emphasis mine].20

The call for solidarity finds positive reception in a sector of the Greek American public sphere, including the media and eminent organizations like AHEPA. Thus, a secular narrative is surfacing, calling for a rewriting of Greek American, but also global Greek, history, that centers on Greek/African convergences. This reframing clearly refrains from idealizing Greek/African relations; it explicitly refuses a celebratory rhetoric. But it finds value in the explicitly selective foregrounding of those linkages that illustrate commitment to common causes. It proposes, in other words, a telling of history based on Greek American/African American mutually beneficial intersections. Looming large are examples of visionary leaders—such as that of Iakovos, who stands as an emblematic figure—but also lesser known activists, professionals, and ordinary individuals who have practiced citizenship based on interracial solidarity:

Less known are the contributions of everyday Greek-Americans to the civil rights struggle. People like Anthony J. Konstant, a Baltimore civil rights advocate and restaurateur who led the way in desegregating restaurants in Maryland. Pota Vallas, of Raleigh, NC, who now at the age of 104, still praises the African-Americans who worked with her in her design and decoration firm, in her own words: “they were more family than employees, I couldn’t have made it without them.” … When a young man named Barack Obama sought to enter the political arena in Chicago, his Greek-American friend Alexi Giannoulias convinced his family and friends to offer invaluable support to the fledgling politician.

When Greeks began their war of independence against the Ottoman Empire, James Williams, a former slave and sailor from my hometown of Baltimore, joined Greek Naval forces and fought gallantly at the battle of the Gulf of Lepanto. Williams died in Greece. When Martin Luther King, Jr., marched on Selma, striding along with him in his black Kalimafki (itself a sign of subjugation originally imposed by Ottoman rulers) was Archbishop Iakovos, leader of the Greek Orthodox Church of America. … When the apartheid regime in South Africa put Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki, and Walter Sisulu on trial in 1963, for their defense Mandela called on his trusted law school classmate and friend, Greek born attorney George Bizos.21

Greek American civic leaders call for re/collecting the global historical archive22 to excavate stories of sacrifice and daring in the name of interracial bonding. In this respect, they call for the making of new knowledge and consequently a transnational and global understanding of Greek history. The practice of positing positive examples as the building block for crafting such history appears to represent a popular version of what Vassilis Lambropoulos coins as “constructive history.” He proposes it as a necessary turn in the humanities and social sciences:

Such a reorientation would shift attention … to structures, orders, and arrangements that have worked well because they were creative, fair, egalitarian, harmonious, self-critical, and open to negotiation, adjudication, and revision. We do not need a history of victors (the triumphalist and nationalist glorification of the past) or their victims (the counter-political record of their discrimination). What we need right now is a history of heroes, of achievements, of virtues, of important works, of effective innovations, of beautiful structures—a history of freedoms, equalities, values, and distinction.23

The narration of global Greek/African pasts in this manner aims to produce useful knowledge for the present, a usable past. It is meant to foster a kind of Greek American citizenship that works toward the becoming of the United States to a polity aligned with its political ideals. Not unlike Iakovos’s vision of the Greek Orthodox Church functioning as an active guardian of American ideals, this secular narrative also invests in the making of a usable past that, according to Demetrios Rhombotis:

inspire[s] us to become more sensitive and equally active when it comes to modern day challenges. A society is always a work in progress and nothing can be taken for granted, we must be vigilant of our freedoms and of our dignity as human beings. The best way to accomplish that is by making sure that all our fellow citizens enjoy the same rights and quality of citizenship as we do. Unfortunately, in the U.S. this isn’t the case yet …24

This passage deserves our attention for additional reasons. It is significant, for instance, that it casts Greek identity as an obligation; a civic duty of advocating values of inclusion and dignity for all. This formulation departs from definitions of ethnic identity as given, based on descent or mere self-ascription; or as mere aesthetic cultural expressions, in food and dance for example, divorced from civic considerations. Instead, identity is achieved via practices of citizenship. It entails a specific set of actions and behaviors: to claim the identity is not enough. It must be proven on the basis of civic criteria. Rhombotis continues:

There were other Greeks—some of them still live in our midst—that proved themselves as Hellenes and courageous human beings during one of the toughest periods in the American History. Aleck Gulas, father of the former AHEPA Supreme President Ike Gulas, was the first, in Birmingham, Alabama, of all places, to open his jazz supper club (Key Club) to African-American musicians!25

One demonstrates cultural identity then through the practice of inclusive citizenship. Notably, the narrative makes a causative link between the particular (Greek cultural identity) and the universal (inclusive citizenship based on civil liberties and equality). It posits a particular value, philotimo, as a constitutive cultural force that has been propelling Greek Americans to act in solidarity with African Americans, and beyond, in encounters between Greek and African people in various contexts. In an essay entitled, “When Philotimo Stood with African-Americans,” published in the Greek American newspaper The National Herald, Andreas Akaras, a political advisor and attorney based in Washington, D.C., draws this connection:

It is also a wonderful opportunity for our community to extend an old hand in friendship to the African-American community. Black History Month is an occasion to examine Hellenism in both its conceptual and practical forms. What role did the high ideals and values of Hellenism play in the legal and social considerations that moved our government in the direction of freedom and liberty? What motivated Hellenes from Baltimore to Johannesburg to stand on the side of liberty, justice, and freedom for all? No matter what we deduce from studied introspection, each of these outstanding Hellenes deserves our recognition, and we must honor their courage and conviction by embracing our Philotimo.26

In expressing civic care for Others this narrative also contributes to the making of the Self. It reflects on what constitutes Greek identity and articulates whom the Greeks should aspire to become in the future.

Akaras promotes a normative definition of Greek identity. He states what defines a Greek, what Greeks ought to do, and how they are expected to behave if they are to remain worthy of their identity. In the context of his writings, Hellenism interweaves cultural elements–specifically philotimo (love of honor)27–with political considerations and is expressed as an identity which acquires substance and meaning via citizenship. Identity must translate into concrete civic practice. Moreover, this culturally driven Greek citizenship extends to global expressions of Hellenism. Its practice in the United States is seen as applicable, for instance, in guiding antiracist practices in Greece. It is transnational in scope.28

Reflecting on Culture as Agency for Social Change

Orthodox clergy and scholars, along with Greek American leaders, connect their respective identities with the practice of citizenship as interracial solidarity. They envision members of their religion and ethnicity internalizing the principle of deification and the value of philotimo, and consequently call upon these members to advocate civil rights. In this aim they see empathy, defined as compassionate understanding of the Other—in this case the African American predicament—as a structure of feeling leading to interracial solidarity. Overall, they assign culture (values, knowledge, and feelings) a constitutive role in the making of a citizen. The belief is that narratives prescribing identity as expressing philotimo or as striving for deification will persuade and in turn shape their intended audiences toward the citizenship model these narratives advocate. What is the potential of these narratives to resonate with their target demographics? They are certainly noble in their stated purposes. But how persuasive will they be? Are ideals alone (philotimo and deification) sufficient as agents for social change?

The idea of identity as moral and civic obligation certainly carries the potential to function as a source of identification. But there are limitations. Orthodox spokespersons for instance acknowledge the sociological reality of the Orthodox collective as an impediment to the narrative of deification as a moral imperative. This is because the authority of the Church to constitute the true meaning of Orthodoxy is diffused, given that interpretations of what constitutes a proper Orthodox life multiply. “We are not as homogeneous as once we might have been,” Anton C. Vrame, Director of Religious Education of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, notes. “Everyone has a blog and a Facebook page or a publishing company, claiming to pronounce what Orthodox Christianity teaches about an issue. For every pronouncement, even from a Church body, there are dozens of responses criticizing it from every angle possible.” Consequently, open public debate on the issue of race in Clergy–Laity Congresses is not what it used to be. According to Dr. Anthon Vrame, Director of the PRAXIS magazine, “Today the Archdiocese has retreated from this level of activity. [Though,] [f]ortunately, the Assembly of Bishops is now taking a more active role.”29 The risk of open conflict and rift within the community may result in institutional reticence and indecisiveness in promoting civic activism as religious necessity. And even if the Greek Orthodox Church issued an official pronouncement in support of “America’s tradition of welcoming ‘people of every nation, tribe, and tongue’ and ‘humans from all walks of life,’” indirectly alluding to President Trump’s executive order on immigration, nothing can guarantee its uniform acceptance by its flock.30 The media, particularly Facebook, are teeming with anti-immigrant narratives by users professing U.S. Greek Orthodox identities.

This brings me to the question of a politics of solidarity based on empathy. Empathy as compassion is an honorable position, an admirable aspect of humanity that counters callousness or indifference against vulnerable populations such as the homeless, the poor, the outcasts, the stigmatized Others. And it certainly may drive human action on behalf of the disenfranchised. It is not certain at all, however, whether experiencing empathy may lead to political action. It may be directed to philanthropy, for instance, and alleviate suffering temporarily, without subverting the conditions that produce poverty. What is more, it may psychologically benefit the empathizer solely, by creating “a false sense of involvement.”31 Congressman Cummings addressed precisely this problem when his speech at the Alliance Reception stressed the absolute necessity of translating empathy into action. Adding to the limits of the empathy discourse, empathy may inspire the empathizer, to generate within this person feelings of internal morality, but “it rarely changes the circumstances of those who suffer.”32 Empathy opens up the Self to the compassionate understanding of Others, a lofty way of being-in-the world. Even if it is not embraced by everyone, it “does not mean we should forsake it.”33 But viewing it as the force for change is erroneously auspicious.34

The secular narrative of philotimo presents its own difficulties too. Theorists of culture acknowledge the power of values in shaping the ways in which human beings act upon the world. But at the same time, they caution that it will be erroneous to “elevate culture as superior to economics or the state” in modifying the world.35 Proposing philotimo, therefore, as an overarching force leading to social change is problematic. The material interests or political ideology of a sector of Greek America may work against accepting philotimo as an obligation for citizenship. Let us recall that some Greek Americans have historically taken positions against Civil Rights activism openly, and vocally, on the basis of material considerations such protecting their property and businesses. In their letters to Archbishop Iakovos, Greek American businessmen in the American South, for example, opposed his civil rights activism on the premise that it jeopardized their business interests and their safety.36 Consideration of protecting home values, but not necessarily racism, have led Americans with roots in southeastern Europe, including Greek Americans, to join the white flight to the suburbs and bypass the potential of interracial solidarities in the 1960s and 1970s. What is more, national ideologies denying racism as an institutional reality in the United States and adhering to the position of the country as a color-blind society may also trump the Greek American sense of philotimo, which may be interpreted in ways other than those subscribed by the narrative I examine here.

Let us also not forget that in the past, in rural Greece, the effectiveness of the practice of philotimo as an obligation to conform to highly valued cultural values relied on two interrelated variables: a relatively homogeneous, face-to-face community that consented to a host of shared moral values and which it actively enforced through mechanisms, which publically shamed the nonconforming person, with grave social and economic implications for this person and his or her family. None of these conditions are in operation in heterogeneous, suburbanized Greek America. Making philotimo the constitutive core of a cultural and civic Greek American identity works rhetorically, as the means to motivate the Greek American public what Greek identity ought to be in the United States, and globally. But the mechanisms for enforcing it are lacking. The central proposition of the narrative that privileges philotimo as the force for social transformation is limited and limiting.37

Conclusion

Greek American and Orthodox people engage in civic activism to safeguard civil rights in American society. The religious and the secular narrative display significant commonalities and, as one would expect, considerable differences in the purpose and means of their activism. They both see themselves as guardians of their respective religious and cultural values, and simultaneously as protectors of national ideals. They approach American identity as a process in the making, and, like Iakovos, they assign themselves the role to shaping the direction of the nation in alignment with its ideals.

One might claim that the construction of identities seen as authentic, measured on their adherence to a particular civic performance, is an answer to the unfolding heterogeneity of U.S. Orthodoxy and Greek America. If identities and their meaning multiply within these religious and cultural fields, the civic-oriented initiatives resort to the authority of theology and cultural values to establish what the aforementioned civic and religious spokesmen see as true identity in a landscape of competing claims. To the question “what does it means to be Orthodox or Greek American,” they offer an encompassing answer, which aims to center these identities around a common civic purpose. They seek a unifying thread in the midst of fragmentation and plurality. In this respect, one might claim that narratives calling for interracial solidarity operate within the modernist view of identity as stable and singular, as identification associated with duties and obligations, therefore counteracting postmodernist views of European American identities as symbolic, that is, as fleeting, situational, and superficial.38

The spokespeople for religious and ethnic groups mobilize religious principles and cultural values respectively to foster citizenship, understood as solidarity with African Americans. This agency emanates partly as urgency to counter heightened racism and ongoing racial discrimination in the society. U.S. Orthodox Christians and Greek Americans draw upon historical examples of their participation in interracial alliances to generate identity narratives that call for advocacy, both in word and action, for inclusive civil rights. In fact, they see such advocacy as an obligation emanating from their respective traditions. Identity in these narratives is seen not as a matter of choice or mere self-ascription, but as a position that requires civic responsibility. One demonstrates identity through specific social practices. Identity is achieved, not given.

Significantly, both narratives make the understanding of how race is lived in this country essential. This call for responsible knowledge of Others as a venue to promote interracial understanding and ultimately engaged citizenship also engages Greek American education, squarely probing scholars to reorient our thinking of Greek America: Greek America not as a singular ethnic group, or as a mere transnational field (in relation to Greece or other diasporas), but as a terrain shaped transculturally, in interaction with other cultures, and interracially, in relation to people of color. The identity narratives call upon Orthodox people and Greek Americans to understand the race and immigration question in the United States. Greek American studies is positioned to contribute to the educational mission of this project, in fact empower it, by producing knowledge that addresses the questions the narratives raise.

What direction will these initiatives take? Will they succeed in entrenching themselves in institutions and in being translated into enduring action? Will there be a public dialogue about the possibilities and limitations of understanding Others across difference? The least Greek American education could do is to produce scholarship mapping these developments, narrating Greek American/African American interfaces, explaining differences and similarities in Greek American and African American experiences, identifying the specific impact of whiteness on members of these two collectives. Or, even more, it could engage in a public dialogue and contribute to the circulation and understanding of these projects.

Acknowledgments

I thank Gregory Jusdanis for his keen insights. An earlier version of this work was presented at the “Homeland-Diaspora Relations in Flux: Greece and Greeks abroad at Times of Crisis,” organized by The Greek Diaspora Project at SEESOX, St Antony's College, University of Oxford, June 22-23, 2018. I thank the organizers and participants for their input.

Yiorgos Anagnostou is Professor in the Modern Greek Program at The Ohio State University. He is the author of Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America (2009, Ohio University Press). He has published extensively on Greek America (https://www.mgsa.org/faculty/anagnost.html).

Notes

1. Michael B. Smith, Rebecca S. Nowacek, and Jeffrey L. Bernstein, “Don’t Retreat. Teach Citizenship,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 19, 2017, accessed February 1, 2018, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Don-t-Retreat-Teach/238923.

2. Aristotle Papanikolaou, “Racism: An Orthodox Perspective,” Public Orthodoxy, January 18, 2018, accessed March 5, 2018, https://publicorthodoxy.org/2018/01/18/racism-orthodox-perspective/.

3. Rev. Fr. Michael Varlamos, “Selma, 1965: When Racism Gazed Upon the Face of Orthodoxy,” PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 6–8.

4. Athanasios Grammenos, “The African American Civil Rights Movement and Archbishop Iakovos of North and South America,” Journal of Religion and Society 18 (2016): 1–19.

5. Ibid., 5.

6. Iakovos, cited in PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 1.

7. † Metropolitan Nicholas of Detroit, PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 3.

8. Georgia Kasamias, “Orthodoxy and Race in Light of Trump’s Inauguration,” Public Orthodoxy, January 19, 2017, accessed March 5, 2018, https://publicorthodoxy.org/2017/01/19/orthodoxy-and-race-after-trump/.

9. Papanikolaou, “Racism: An Orthodox Perspective.”

10. Michael B. Smith, Rebecca S. Nowacek, and Jeffrey L. Bernstein. “Introduction: Ending the Solitude of Citizenship Education,” in Citizenship Across the Curriculum, edited by Michael B. Smith, Rebecca S. Nowacek, Jeffrey L. Bernstein, Pat Hutchings, Mary Taylor Huber, 1–12 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 5.

11. James A. Banks, Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society (Teachers College Press, 1997), 14.

12. Pearl Rosenberg M., “Underground Discourses: Exploring Whiteness in Teacher Education,” in Off White: Readings on Race, Power, and Society, edited by Michelle Fine, Lois Weis, Linda C, Powell, and L. Mun Wong (New York and London: Routledge, 1997), 79–89. A thread in critiques of empathy stems from alternative definition of empathy. While the conventional view of empathy entails “having an appropriate emotion triggered by another person’s emotion,” some critics see empathy as only “occur[ing] when you have the identical or mirror emotion to another person” (Simon Baron-Cohen, “Empathy Is Good, Right? A New Book Says We’re Better Off Without It,” The New York Times, December 30, 2016, accessed August 26, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/30/books/review/against-empathy-paul-bloom.html).

13. For the centrality of empathy in Greek Orthodoxy and Greek America as the means to interracial solidarity see Yiorgos Anagnostou, Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009).

14. Papanikolaou, “Racism: An Orthodox Perspective.”

15. Georgia Kasamias, “Orthodoxy and Race in Light of Trump’s Inauguration.”

16. The expression of Greek affinities with African Americans may blur the boundaries between the secular and the religious. The secular collaboration between a Greek American educational leader and an African American one, for instance, to “support immigrants and refugees and the African-American community,” in Allegheny County, was expressed in the interfaith event: “Cursed We Bless; Persecuted We Endure” (See Dan Gigler, “Greek Orthodox Support of King at Selma March Recalled,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 12, 2018, accessed March 18, 2018, http://www.post-gazette.com/local/city/2018/03/12/Faiths-join-forces-to-honor-MLK-and-Selma-marchers/stories/201803120069). Similarly, in reflecting on personal and collective solidarities between Greek Americans and African Americans, writer Apollo Papafrangou found inspiration in Martin Luther King Jr.’s linking the ancient Greek concept of agape with theological notions on the “love of God.” See Apollo Papafrangou, “May We Get There with You: On Oakland, MLK, and Greek Allies,” January 19, 2016, accessed January 25, 2016, https://apollopapafrangou.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/may-we-get-there-with-you-on-oakland-mlk-and-greek-allies/. For an example of a local initiative of joint activism between Greek Americans and African Americans in Pennsylvania, see Dan Gigler, “Greek Orthodox Support of King at Selma March Recalled.” In the words of one of the organizers, Greek American Nick Giannoukakis, “I felt that an outreach, sensitizing sister communities about our contribution and positive actions to their own progress and place in America, was part of this admittedly lofty endeavor” (unpublished interview with Yiorgos Anagnostou, May 2018).

17. “African and Greek American Alliance Reception,” March 27, 2013, accessed May 1, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bqhwprFl3c&t=1182s.

18. “A Discussion on ‘Hellenism in the Public Service’ Featuring Congressman John Sarbanes,” Hellenic News of America, November 7, 2102, accessed May 1, 2018, https://hellenicnews.com/a-discussion-on-hellenism-in-the-public-service-featuring-congressman-john-sarbanes/. Congressman John Sarbanes (D–MD), AHEPA, and a host of political, cultural, and religious Greek American leaders condemned President Donald Trump’s Executive Order, “which bans refugees from Syria indefinitely and places strict control on people from Muslim-majority countries” ( Gregory Pappas, “High Profile Greek American Individuals, Groups Speak Out Against Trump Immigration Executive Order,” The Pappas Post, February 5, 2017, accessed June 25, 2018, http://www.pappaspost.com/high-profile-greek-american-individuals-groups-speak-trump-immigration-executive-order ).

19. On the various definitions of Hellenism, see Gregory Jusdanis, “Hellenisms,” Modern Greek Studies (Australia and New Zealand) 3 (1995): 97–115.

20. “Connected through Time: Greek- and African-Americans Unite in Baltimore,” The National Herald , April 18, 2013, accessed April 20, 2018, https://www.thenationalherald.com/2512/connected-through-time-greek-and-african-americans-unite-in-baltimore/.

21. Andreas Akaras, “When Philotimo Stood with African-Americans,” The National Herald, February 14, 2013, accessed March 25, 2018, https://www.thenationalherald.com/3251/when-philotimo-stood-with-african-americans/.

22. On the practice of re/collecting the archive to rewrite Greek American history, see Yiorgos Anagnostou, “Re/collecting Greek America: Reflections on Ethnic Struggle, Success and Survival,” Journal of Modern Hellenism 31 (Fall 2015): 148-175, http://journals.sfu.ca/jmh/index.php/jmh/article/view/26.

23. Vassilis Lambropoulos, “Modern Greek Studies in the Age of Ethnography,” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 15., no. 2 (October 1997): 197–208.

24. Demetrios Rhombotis, “Black History Month and the Greeks,” Greek Reporter USA, February 18, 2014, accessed March 15, 2018, http://usa.greekreporter.com/2013/02/18/black-history-month-and-the-greeks/.

25. Ibid.

26. Akaras, “When Philotimo Stood With African-Americans.”

27. In rural modern Greece, philotimo (love of honor) functioned as a social mechanism to reproduce the dominant moral ideals–about sexuality, familial obligations, parental authority–of the relatively homogeneous community. The community enforced these ideals by rewarding those who conformed while shaming in public those who dishonored them. “The traditional philotimo has been transfigured but is still recognizable” in contemporary Greek America, “in the appreciation of the grand gesture as well as displays of personal generosity”; see Charles Moskos, Greek Americans: Struggle and Success (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1980), 93. Most recently, there has been a concerted institutional effort to present philotimo as the single, foremost value that has been defining Greek and Greek American cultures through time. It is seen as an invaluable national asset that must be passed on to the next generation. The “Oxi Day Foundation” (https://www.oxidayfoundation.org/philotimo/the-greek-secret/) has produced a video featuring prominent Greek Americans defining it. It is seen as a constellation of values including compassion for others, “doing what is right,” advocating the “greater good,” courage and personal sacrifice, “a binding undercurrent” that permeates Greek America. It is understood as something “uniquely Greek,” and inherent to the biology of the Greek people, “in our DNA.” It is posited as “the Greek secret,” which explains the political, cultural and social behavior of the Greeks, doing the “right thing,” in key moments of Greece’s history during the WWI, WWII (resisting surrender to Mussolini’s ultimatum and protecting Greek Jews during the Nazi occupation) and the Cold War. It is also the underlying cause propelling Greeks abroad to socioeconomic success. According to Bob Costas, it represents “the Greek spirit what’s right and what’s honorable even when one’s interests and may be even one’s life are placed on peril” (“Philotimo: The Greek Secret,” Oxi Day Foundation, 2014, accessed January 1, 2015, https://www.oxidayfoundation.org/philotimo/the-greek-secret/ . It is now widely proposed as the defining feature of the Greek diaspora (see Georgia Logothetis, “What does it Mean to be part of the Hellenic Diaspora?” accessed May 5, 2018, https://medium.com/@HellenicLeaders/what-does-it-mean-to-be-part-of-the-hellenic-diaspora-5dfa442853d7 ). It is circulating transnationally as it was embraced by Antonis Samaras, Greece’s Prime Minister at the time, who “made this subject a prominent part of his major speech to the nation.”

28. Andreas Dracopoulos, copresident of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, which donated two million dollars toward the Iakovos Reflection Area at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, also sees civil rights activism transnationally, applicable to Greek America and Greece (“Archdiocese Spotlight Stavros Niarchos Foundation’s Iakovos Donation,” The National Herald, December 12, 2015, accessed March 25, 2018, https://www.thenationalherald.com/109527/archdiocese-spotlights-snf-donation-iakovos-honor/ ). This is also the position of Demetrios Rhombotis, “Black History Month and the Greeks.” For an analysis of the discourse on Greek transnational citizenship see, Yiorgos Anagnostou, “Greek Diaspora Citizenship,” unpublished presentation at the conference “Homeland-Diaspora Relations in Flux: Greece and Greeks Abroad at Times of Crisis,” organized by The Greek Diaspora Project at SEESOX, June 22-23, 2018, St Antony's College, University of Oxford, http://seesoxdiaspora.org/.

29. Anton C. Vrame, “Standing Up, Speaking Out,” PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 24.

30. See Gregory Pappas, “Greek Orthodox Archbishop of America Issues Statement on Treatment of Strangers; Alludes to Trump Immigration Executive Order But Doesn’t Mention It,” The Pappas Post, February 4, 2017, accessed August 1, 2018, http://www.pappaspost.com/greek-orthodox-archbishop-america-issues-statement-treatment-strangers-alludes-trump-immigration-executive-order-doesnt-mention/ . Most recently, the Metropolitan of Chicago explicitly castigated the administration’s “zero tolerance” policy. See Darden Livesay, “Metropolitan Nathanael of Chicago: Trump Administration’s Immigration Policy ‘Barbaric,’” The Pappas Post, June 19, 2018, accessed June 25, 2018, http://www.pappaspost.com/metropolitan-nathanael-of-chicago-trump-administrations-immigration-policy-barbaric/.

31. Pearl M. Rosenberg M., “Underground Discourses: Exploring Whiteness in Teacher Education,” 83. In addition, empathy may generate narratives of self-victimization among those privileged by race and class, creating a false sense that all hardships “are the same” and “obscuring the ways that racist domination impacts on the lives of marginalized groups in our society” (83).

32. Amy Shuman, Other People’s Stories: Entitlement Claims and the Critique of Empathy (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005): 5.

33. Gregory Jusdanis, A Tremendous Thing: Friendship from the ‘Iliad’ to the Internet (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014), 12.

34. For an attempt to reconcile the “love ethnic” of Christianity with institutional politics that aim to redress class and racial injustices, see Rosemary Cowan, Cornel West: The Politics of Redemption (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press, 2003).

35. See Gregory Jusdanis, “Beyond National Culture?” boundary 2 22, no.1 (Spring 1995): 27.

36. Athanasios Grammenos, “The African American Civil Rights Movement and Archbishop Iakovos of North and South America.”

37. The narrative of philotimo requires critical reflection. I am sketching a critique here on a topic that requires a wider conversation. First, it is absolutely necessary to do away with the idea of philotimo as a biological trait. The historical fact of some Greeks behaving dishonorably, collaborating with the Nazis, for instance, discredits the idea of philotimo as a Greek biological attribute. (And if this is indeed a biological trait why there should be an effort to pass it on to the next generation as the narrative aims?) Second, the understanding of philotimo as the causative force of governmental positions and behavior neglects to take into account those material and political considerations that enter into a government’s and a people’s decisions to act in one way and not another. Ironically, to elevate it as the cause of Greek diaspora socioeconomic mobility, as this narrative does, works against the understanding of how the social structures of the home countries favored immigrants from European Americans over African Americans, as scholarship has convincingly shown. This neglect underlines a contradiction in the philotimo narrative: on the one hand the narrative values education, but on the other hand it neglects to take into account scholarship that illuminates the complexities of European American socioeconomic ascent.

38. For a critique of symbolic ethnicity, see Yiorgos Anagnostou, “A Critique of Symbolic Ethnicity: The Ideology of Choice?” Ethnicities 9, no. 1 (2009): 94–122.

Works Cited

“A Discussion on ‘Hellenism in the Public Service’ Featuring Congressman John Sarbanes.” Hellenic News of America, November 7, 2102. Accessed May 1, 2018. https://hellenicnews.com/a-discussion-on-hellenism-in-the-public-service-featuring-congressman-john-sarbanes/.

“African and Greek American Alliance Reception.” March 27, 2013. Accessed May 1, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bqhwprFl3c&t=1182s.

Akaras, Andreas. “When Philotimo Stood With African-Americans.” The National Herald, February 14, 2013. Accessed March 25, 2018. https://www.thenationalherald.com/3251/when-philotimo-stood-with-african-americans/.

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “A Critique of Symbolic Ethnicity: The Ideology of Choice?” Ethnicities 9 no. 1 (2009): 94–122.

– – –. “Re/collecting Greek America: Reflections on Ethnic Struggle, Success and Survival.” Journal of Modern Hellenism 31 (Fall 2015): 148–175. http://journals.sfu.ca/jmh/index.php/jmh/article/view/26 .

– – –. “Greek Transnational Citizenship.” Paper presented at the “Homeland-Diaspora Relations in Flux: Greece and Greeks abroad at Times of Crisis,” organized by The Greek Diaspora Project at SEESOX, St Antony's College, University of Oxford, June 22-23, 2018. http://seesoxdiaspora.org/.

Banks, A. James. Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1997.

Cowan, Rosemary. Cornel West: The Politics of Redemption. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Press (2003).

“Connected through Time: Greek- and African-Americans Unite in-Baltimore.”

The National Herald , April 18, 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018. https://www.thenationalherald.com/2512/connected-through-time-greek-and-african-americans-unite-in-baltimore/.

Dracopoulos, Andreas. Cited in “Archdiocese Spotlight Stavros Niarchos Foundation’s Iakovos Donation.” The National Herald, December 12, 2015. Accessed March 25, 2018). https://www.thenationalherald.com/109527/archdiocese-spotlights-snf-donation-iakovos-honor/.

Gigler, Dan. “Greek Orthodox Support of King at Selma March Recalled.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 12, 2018. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://www.post-gazette.com/local/city/2018/03/12/Faiths-join-forces-to-honor-MLK-and-Selma-marchers/stories/201803120069.

Grammenos, Athanasios. “The African American Civil Rights Movement and Archbishop Iakovos of North and South America.” Journal of Religion and Society 18 (2016): 1–19.

Jusdanis, Gregory. “Hellenisms.” Modern Greek Studies (Australia and New Zealand) 3 (1995): 97–115.

– – –. “Beyond National Culture?” boundary 2 22 no.1 (Spring 1995): 23–60.

– – –. A Tremendous Thing: Friendship from the ‘Iliad’ to the Internet. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2014.

Kasamias, Georgia. “Orthodoxy and Race in Light of Trump’s Inauguration.” Public Orthodoxy, January 19, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2018. https://publicorthodoxy.org/2017/01/19/orthodoxy-and-race-after-trump/.

Lambropoulos, Vassilis. “Modern Greek Studies in the Age of Ethnography.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 15, no. 2 (October, 1997): 197–208.

Livesay, Darden. “Metropolitan Nathanael of Chicago: Trump Administration’s Immigration Policy ‘Barbaric.’” The Pappas Post, June 19, 2018. Accessed June 25, 2018. http://www.pappaspost.com/metropolitan-nathanael-of-chicago-trump-administrations-immigration-policy-barbaric/.

Logothetis, Georgia. “What Does it Mean to Be Part of the Hellenic Diaspora?” Accessed May 5, 2018. https://medium.com/@HellenicLeaders/what-does-it-mean-to-be-part-of-the-hellenic-diaspora-5dfa442853d7.

Moskos, Charles. Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

† Metropolitan Nicholas of Detroit, PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 3.

Papafrangou, Apollo. “May We Get There With You: On Oakland, MLK, and Greek Allies.” January 19, 2016. Accessed January 25, 2016. https://apollopapafrangou.wordpress.com/2016/01/19/may-we-get-there-with-you-on-oakland-mlk-and-greek-allies/.

Papanikolaou, Aristotle. “Racism: An Orthodox Perspective.” Public Orthodoxy, January 18, 2018. Accessed March 5, 2018. https://publicorthodoxy.org/2018/01/18/racism-orthodox-perspective/.

Pappas, Gregory. “Greek Orthodox Archbishop of America Issues Statement on Treatment of Strangers; Alludes to Trump Immigration Executive Order But Doesn’t Mention It.” The Pappas Post, February 4, 2017. Accessed August 1, 2018. http://www.pappaspost.com/greek-orthodox-archbishop-america-issues-statement-treatment-strangers-alludes-trump-immigration-executive-order-doesnt-mention/.

Pappas, Gregory. “High Profile Greek American Individuals, Groups Speak Out Against Trump Immigration Executive Order.” The Pappas Post, February 5, 2017. Accessed June 25, 2018. http://www.pappaspost.com/high-profile-greek-american-individuals-groups-speak-trump-immigration-executive-order.

“Philotimo: The Greek Secret,” Oxi Day Foundation, 2014. Accessed January 1, 2015.

https://www.oxidayfoundation.org/philotimo/the-greek-secret/ .

Rhombotis, Demetrios. “Black History Month and the Greeks.” Greek Reporter USA, February 18, 2014. Accessed March 15, 2018. http://usa.greekreporter.com/2013/02/18/black-history-month-and-the-greeks/.

Rosenberg, Pearl M. “Underground Discourses: Exploring Whiteness in Teacher Education.” In Off White: Readings on Race, Power, and Society, edited by Michelle Fine, Lois Weis, Linda C. Powell, and L. Mun Wong, 79–89 (New York and London: Routledge, 1997).

Shuman, Amy. Other People’s Stories: Entitlement Claims and the Critique of Empathy . (Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

Smith, Michael B., Rebecca S. Nowacek, and Jeffrey L. Bernstein. “Don’t Retreat. Teach Citizenship.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 19, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2018. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Don-t-Retreat-Teach/238923 .

Smith, Michael B., Rebecca S. Nowacek, and Jeffrey L. Bernstein. “Introduction: Ending the Solitude of Citizenship Education.” In Citizenship Across the Curriculum, edited by Michael B. Smith, Rebecca S. Nowacek, Jeffrey L. Bernstein, Pat Hutchings, Mary Taylor Huber, 1–12 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Varlamos, Rev. Fr. Michael. “Selma, 1965: When Racism Gazed Upon the Face of Orthodoxy.” PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 6–8.

Vrame, Anton C. “Standing Up, Speaking Out.” PRAXIS 14, no. 2 (Winter 2015): 24.