Greek/American Belonging in the Poetry of George Kalogeris

by Ilana Freedman

A critical introduction to George Kalogeris. Reflections on a trilogy in the making: Guide to Greece (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2018); Winthropos (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2021); and the poems “Frigidaire,” “Memorial Day,” “Grape Leaves at Chloe’s,” “Umbrella,” “Roget’s Thesaurus,” “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” and “Tiléfonos” (published in Erγon)

When, in George Kalogeris’s poem “Winthropos,” the father asks his son “ And if you get lost, Yorgáki, what will you do?” the son answers “‘I’ll find some older people and tell them my name.’” “Anything else?” the father prompts, but the boy’s promise that he will tell them where he lives still does not suffice:

And where is that? “Forty-five Locust Ave.”

And where is that? “Winthrop.” Then comes his vague,

Winthrop, Yorgáki? Or is it Winthropos ...

The puzzle of “Winthropos” continues to perplex this boy long after he becomes one of those “older people.” The poem invites us to read its speaker as the retrospective voice of Kalogeris himself, who concludes that “Winthropos” is

Obvious, unavoidable.

It tells me the answer to the Sphinx’s riddle

is Anthropos. My father pulling my leg.

Where exactly “home” is in the poetry of Winthropos (2021), Kalogeris’s most recent collection, and Guide to Greece (2018), his collection before it, remains enigmatically beyond reach. One specular example is “Define Hellas,” the final line of Guide to Greece (130). The imperative is not Kalogeris’s own but that of the second-century AD Macedonian king Philip V, responding to the Roman decree to withdraw his troops beyond Greek borders. Its challenge timelessly predicates the puzzle of Kalogeris’s collection writ large: the impossibility of defining “Greece” itself.[1]

Kalogeris’s poetry most often envisions what is and is not “Greece” by reimagining what is and is not “home.” Born to immigrant parents from the rural Peloponnese and raised within the diasporic Greek community of Winthrop, Massachusetts, Kalogeris’s layered definition of “home” retraces the sliding solidus of Greek/American. Yet the homes in his poems are not merely his own. Traces of his families’ villages, ancient Hellenic sites, and remote landscapes of Asia Minor and Magna Graecia populate his verse. He associates his own childhood and his ancestral lineage with contemporary histories and archaic pasts alike. Kalogeris is by no means the first poet to write about what it means to be between and betwixt Greece and America in recent decades. His collections should be considered alongside those such as Yiorgos Chouliaras’s Δρόμοι της μελάνης (Roads of Ink) (2005), Stephanos Papadopoulos’sThe Black Sea (2012), and Adrianne Kalfopoulou’s A History of Too Much (2018), books which also offer glimpses into the intimacies of Greek/America and work to reconcile the pride of transcultural heritage with the burden of familial trauma. Yet Kalogeris is uniquely at home in liminality itself. As these new poems published in Ergon so poignantly affirm, belonging can be found in the search for the past and even in the impossibility of its recovery.

*

When I sound out Kalogeris father’s paronomasia in my head, I cannot help but recall a very different Greek pun about the “humanity” of home from a poet whom Greece offered a refuge from his New England upbringing. Written before the start of the military dictatorship (1967-1974), James Merrill’s “Neo-Classic” (from his unpublished poem “Two Double Dactyls”) dates to when he still lived in his house in Athens. Amidst growing public demonstrations and increased censorship, the poem hints at Merrill’s own concession that “he was a rich American [in Greece] at a moment when it was unpopular and possibly even dangerous to be one”:

“Neon lights, discotheques ...

“Landlord, what’s happening?”

“Άνθρωπηστήκαμε,

Go home, U.S.”

(Hammer 2015, 388; Merrill 2001, 814)

Merrill’s editors translate the Greek word as “we have become human beings” (814). The lines sardonically suggest that not all people are treated the same when Americans are free to enjoy themselves in Greece while their Greek “landlords” suffer under the inhuman oppressions of the Colonels. Merrill’s self-deprecating Athenian eviction notice seems a far cry from Kalogeris’s celebratory “Winthropos”—a New England city more alive because Greek immigrants are there “becom[ing] human beings.” Yet, despite their antithetical takes on Greek/American (dis-)belonging, the anthropic puns of Kalogeris and Merrill share an awareness that defining “humanity” itself entails categories of exclusion.

Kalogeris does not shy away from the enforced exclusions that displaced his own family across generations nor does he acquiesce to “το μηχανισμό της καταστροφής” (“the mechanism of catastrophe”)[2] that precipitated them. His parents, his grandparents, and his other relatives suffered through the atrocities of the Asia Minor Disaster (1922), the devastations and massacres of the German Occupation (1941-1944), the internal traumas of the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), and the economic and social austerities of a post-war Greek state. But Kalogeris recognizes that the realities of others are not necessarily his own. This approach to the layered subjectivities of diasporic experience—from the personal to the familial to the more broadly historical—posits a shifting definition of “Greekness,” echoes of which can be found within Kalogeris’ own Greek/American past. His cross-cultural topographies encourage readers to recognize not only a heterogeneous Greek diaspora but also, within this diaspora, a “Greece” that exists beyond the Greek state itself, the geopolitical borders of which been continuously remapped throughout the past century. To this end, Theodoros Rakopoulos argues that a growing current of Greek diasporic poetry resists “the idea of απόδημος Ελληνισμός (apódimos Εllinismós, outward migrating Hellenism)” given that

the apódimos notion to conceptualize Greeks abroad is limited and limiting: it frames Greeks or Greekness as nationhood or as a linguistic community that derives from or refers to a certain, very specific homeland, the South Balkan country known as Greece (2016, 161).

Kalogeris belongs to this aforementioned category of Greek/American poets who—to borrow the poet George Economou’s word—“transcomposite”[3] the cultural topologies of “Greekness” in order to subvert the ideal of the “homeland” as a homogenous national center.[4] And Kalogeris remains, without doubt, a poet preoccupied with that which lies beyond fixed determinations of autochthony.

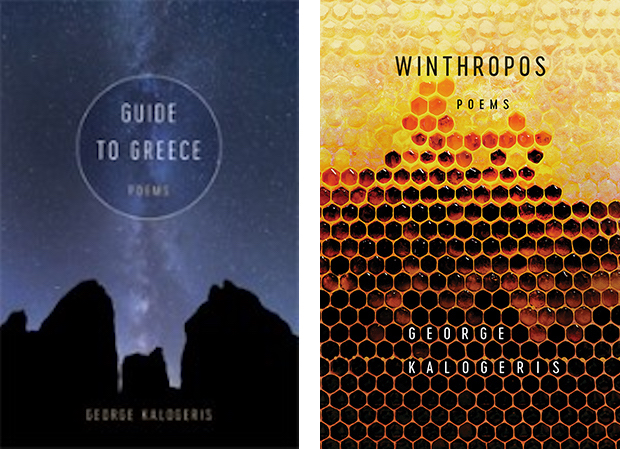

While Guide to Greece and Winthropos are relatively new arrivals on the Greek/American scene, Kalogeris’s previous publications establish him as a longstanding poet and scholar within its literary traditions and cultural criticisms. Also a highly respected translator, his versions of Cavafy, Baudelaire, Mandelstam, Pindar, and Sappho, among others, appear in his collection Dialogos: Paired Poems in Translation (2012). Moreover, his translations have set the stage for recent English language remakings of (ancient) Greek lyric. In his somewhat critical review of Evan Jones’ recent translations of Cavafy, for instance, David Ricks pairs Kalogeris’s English translations of Cavafy with those of Merrill, admiring both as “crafty but not licentious re-imaginings by poets fluent in modern Greek” (2021, 391). “Crafty but not licentious” are two adjectives that could be easily applied to Kalogeris’s own verse. He was the 2018 recipient of the James Dickey Prize for Poetry, and his poems have featured in Christopher Ricks’s anthology Joining Music with Reason (2010) as well as an array of acclaimed literary magazines in the past decades. These two latest collections mark, in many ways, the culmination of a poet of Greek/American letters whose contributions have shaped the contours of its transnational, intellectual community. But Kalogeris is far from finished. Guide to Greece and Winthropos are part of a trilogy of collections, and its final volume, Magna Graecia, is forthcoming. Thus, it is in this Janus-faced moment of the trilogy in the making—wherein Winthropos looks back at Guide to Greece while gazing forward toward Magna Graecia—that these seven poems featured here in Ergon (eventually to appear in Magna Graecia) come to rest.[5]

What distinguishes Kalogeris’s poetry is its interweaving of classical intertexts (Homer, Pindar, Euripides, Horace) and lyric traditions of the modern Greek and other European poets whom he translates (Cavafy, Seferis, Rilke) with the poetic influences of the mentors who taught him while he was a graduate student at Boston University (especially Derek Walcott and Seamus Heaney). Yet, his poems’ self-referential choreographies and metrical schemes—for instance, expressing demotic Greek phrases in classical Greek hexameter—are very much his own. Kalogeris invites his readers to share in what “Greek/Americaness” has come to mean to him—the palimpsestic memories of a young child at home and in school, a graduate student of poetry, a scholar of ancient Greek and Latin, and a member of an immigrant community. In this regard, his collections reanimate ancient archives and scenes with the same dedication with which they commemorate relatives, family friends, schoolteachers, and literary guides from his past.

Given the richness of these intertextual debts, Kalogeris could easily leave readers feeling lost within a labyrinth of references and allusions. But I find the opposite to be true. His poems often recall intimate moments and formative relationships, both literal and literary, which he grounds within a symbology of objects. Kalogeris himself speculates that Heaney’s poems about the well, water pump, and pitchfork—“obdurate” symbols of the family farm where the poet spent his childhood—may have helped him to conceive his own reimaginings.[6] Heaney’s speaker in “Terminus” (1987) famously celebrates the liminality of his Northern Irish roots, claiming that “Two buckets were easier carried than one. / I grew up in between” (4). Kalogeris’s chosen symbols, by comparison, tend toward things that stretch, decay, interweave, or disperse akin to diaspora itself, as we see in each of the poems appearing now in Ergon. Consider the “Frigidaire” aging in the family kitchen; the smoke of the vigil lamp wafting beyond the cemetery on “Memorial Day”; the “tendrils” of vines intwining myth and history in “Grape Leaves at Chloe’s”; the superstitious omen of the black “Umbrella” expanding indoors; the entry for “labyrinth” in “Roget’s Thesaurus” entangling with the calamitous fate of the godparents who gifted it; the ancient footnote anxiously appending Thucydides’ “The History of the Peloponnesian War”; and the cord of the “Tiléfonos” coiling in knots: all reperform the inherited (im)materialities of Kalogeris’s Greek/American past.

Yet the symbolic referents of these titular objects prove Heraclitean here—they never “step in the same river twice.” Kalogeris breaks the mold once he is finished, giving us a fresh casting for each poem, and sometimes more than one within a poem itself. Take “Tiléfonos,” for example, which already, in the Greek etymology of its title, anticipates the “τῆλε” (“far”) “φωνή” (“voice”) that follows:

No wireless cell or instant message. But current

Enough to recall those ancient long-distance calls

That always seemed to ring around suppertime,

Once every few weeks. The calls from overseas.

And always in that other, more difficult language.

And somehow via that rubber spiral cord

Just stretchy enough to reach across our kitchen,

To where she stood, wiping her hands on her apron,

And turning knobs of the stove, her head to one side,

Receiver cradled between her shoulder and ear.

Tiléfonos.

Cooking at her stove top in Winthrop, the mother periodically receives distressing news from her relatives in Greece. Should “her stricken face grow pale in the rising steam,” then the children listen helplessly below, where “that long beige cord was on our level, / And kept us kids in the conversional loop.” This winding “looped” cord mimics the oceanic boustrophedons[7] of these transatlantic conversations. But its tangible filament also connects maternal despair and childhood apprehension within the immediacy of the kitchen scene (“We felt it in our guts—that sinewy coil / That somehow stretched across the Atlantic Ocean / And tied itself in knots when she hung up”). Its tangled expanse symbolizes the one-sidedness of talking on the phone, and the young children sat beneath such conversations, who grasp something of the “puzzle” received, but fear that it is has no answer.

“Frigidaire” is also set in Kalogeris’s childhood kitchen. Here, the distant Greek voice makes itself known through the paradoxical silence of his paternal grandfather, who lived through the war austerities and massacres of his village during the German Occupation. The poem’s title refers to the family’s newly purchased refrigerator—a “frozen” home for their American products:

It stood in our kitchen, as stolid as it was solid:

That new refrigerator, pristine as a block

Of Parian marble, freshly cut from the quarries.

Each time you opened the door of our Frigidaire

You were face to face with a breath of colder air,

And that much more aware of the silent elder

With snow-white hair, and his blank unreadable stare.

He too was new to us. We called him Papou.

He came from Greece. His village was very poor.

Whatever happened there, it was also here—

But frozen in the unspoken. My father’s father

Sat by our kitchen window. And all afternoon

For one whole summer watched over us kids without

A single word of English. And right up until

Our parents got home from work, politely refusing

An Eskimo Pie or a glass of lemonade.

As if he’d steeled himself against the Promised

Land of milk and honey, aglow with one

Sweet pull of the shiny handle.

Despite the young boy’s initial association of these two “new” additions to the home—that chilly Frigidaire and the frigid grandfather sitting beside it—it soon becomes clear that the grandfather wants little to do with that which the ice box luxuriously contains. Like the “Long distance sorrow” of the relative caller in “Tiléfonos,” the grandfather’s past is unreachable to his grandchildren. He remains a “frozen” vestige of the traumas that they are too young to understand.[8] Intriguingly, in a poem about people aging, it is the Frigidaire itself that does not stand the test of time. At first, its new age industry is likened to something timeless, “a block of Parian marble.” But it deteriorates much more quickly than Greek stone; soon the letters of the brand name on the door crumble, leaving “a row of blackened holes across the glazed enamel.” Suddenly, the poem’s Heraclitean “river,” with its rinsing currents of time, reconfigures, and the speaker steps next into unknown waters. The worn and torn refrigerator no longer recalls the grandfather but instead the Greek village that he left behind. There, much older, the speaker transverses “an open field,” where, “not far from the sheep folds,” lies

That upright oblong slab of whitewashed stucco ...

It’s still the summer when a door of moonlight

Opens wide in the dark of our ancient kitchen,

And just as a chilly fluorescence floods my face

And I’m caught red-handed on a midnight raid,

My cousin shows me where the shooters stood.

What the young boy could not imagine illuminates his face all these years later with a “chilly fluorescence,” like that of the Frigidaire, only now its light shines on the place where villagers were once executed. The immediate traumas of the site and the distant presence of the grandfather who witnessed them now intertwine in the speaker’s consciousness. A history this unfamiliar requires the familiar chill of the family refrigerator to register its disturbances.[9]

Intertwined memories of a Greek/American “home” far removed also occupy the remaining poems. In “Grape Leaves at Chloe’s,” ostensibly delicious grape leaves served at an upscale restaurant pale beside the memory of the dolmáthes of the speaker’s maternal grandmother. The second are νόστιμες by definition, given that the Greek word for “delicious” is an adjectival derivation of “νόστος” meaning “homecoming.” The recollection of these grape leaves—and the grandmother “mutter[ing]” and “stirring the ladle” above them—makes the speaker also think of the father’s mother, “As if one grandmother conjured the other’s ghost.” This second matriarch remains a mystery. Kalogeris revealed to me that his uncle swore that German soldiers threw her onto a fire after she attempted to stop them from taking her family’s gramophone. Her “obdurate ghost” already appears in the poem “RCA Victor,” from Winthropos, clutching at that “brazen O of the [gramophone’s] horn” (78). Remembering Euripides’ Bacchus, who grieves at the vine covered grave of his mother Semele, the speaker of “Grape Leaves at Chloe’s” goes on to wonder if this grandmother too, like Semele, “turned to ash in the flash and scorch / of inconceivable thunder.” Consider that “inconceivable” cleverly plays on the myth itself. Semele conceived Bacchus in her womb but then died because of her final wish to conceive of his father’s divinity, incinerated by the lightning and thunder of his true form, while Zeus saved the fetus by sewing him into his thigh from which he was later born. Only, the lyrics interweaving of ancient myth and familial history does not end there. In the opening lines of Euripides’ Bacchae, Bacchus praises his grandfather Cadmus for constructing his mother’s grave—“θυγατρὸς σηκόν: ἀμπέλου δέ νιν / πέριξ ἐγὼ 'κάλυψα βοτρυώδει χλόῃ” (“the shrine of his daughter, which now I have covered all around with the cluster-bearing grapevine”) (11–12). Her protected, sacred “home” after death prefigures the speaker’s own nostos to the house of this “other” grandmother—a home never spoken of by the parents—at which “tendrils climb[ed] all over the porch” and where, only from other villagers, he at last learns of the German Occupation. The twisting and sometimes obscuring vines in the poem recall the difficulty of returning “home.” And its own lines grow in reverse, recounting a genealogy of loss that begins with the disappointing grape leaves of a fancy American restaurant, returns to the longed for dolmáthes of one grandmother’s immigrant kitchen, and ends with the barely visible devastations of the other grandmother’s Greek village.

The speakers of Kalogeris’s poems often question what it means to belong to more than one place at once, challenging accepted ideas about who belongs and does not belong to the Greek “homeland” throughout the past century. Cavafy, who wrote so often about times when “Greekness” transcended the boundaries of language, culture, and religion, has undeniably influenced Kalogeris’s approach. To my mind, Kalogeris’s poem “The History of the Peloponnesian War” especially bears a trace of Cavafy’s “Καισαρίων” (“Kaisarion”) (1918). Cavafy’s twentieth-century Alexandrian speaker consults a volume of inscriptions about the Ptolemies to check a date, claiming that he would have put the book down “ἄν μιά μνεία μικρή, / κι ἀσήμαντη, τοῦ βασιλέως Καισαρίωνος / δέν εἵλκυε τήν προσοχή μου ἀμέσως…” (“had not a brief / insignificant mention of King Kairsarion / suddenly caught my eye…”) (154–155). Cavafy refashions this “ἀσήμαντη” (“insignificant”) reference to an ancient Roman-Egyptian royal ephebe and his untimely murder as an erotic enigma. Kalogeris, by comparison, dwells on the marginalia transcribed by an ancient figure from the reign of Augustus Caesar. After discovering the historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ footnote to Thucydides’History of the Peloponnesian War,[10] his speaker is surprised by the lasting relevance of its confession:

It’s in an anxious footnote to his Commentary

That one can hear Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Worrying aloud about his fellow Hellenes,

And how those readers might react to Thucydides’ text:

“Although by now it’s almost four-hundred years in the past,

I know that there are those who still might find the subject

Matter too personal—and so much so that some

Might not be able to get beyond the Introduction.”

O studious Dionysius of Halicarnassus:

The great Thucydides wrote the book on Greeks killing Greeks

But it’s your footnote that brings my relatives to life.

And so much so, that even now I can hear the ancient,

Anxious, broken English of my immigrant uncles—

The ones who came from Sparta and Arcadia,

And never managed to get beyond a sentence or two

Whenever they tried to tell us about the Civil War.

In “bringing to life” the speaker’s relatives, the footnote resurrects their corresponding grief toward internal Greek strife.

This revitalization brings me back to the scene in Homer’s Iliad, when Zeus “ἐνέπνευσεν μένος ἠΰ” (“breathes great force”) into the horses of Achilles to cease their grieving for Patroclus (Iliad, 17: 456). Intriguingly, Cavafy alters this divine intervention in his own “Τα Άλογα του Αχιλλέως” (“The Horses of Achilles”) (1987); according to his speaker, the horses never stop weeping.[11] In my mind, these revised immortal horses eternally mourn on the battlefield very much like Dionysius worriedly exhales in his footnote. In Kalogeris’s poem, then, it is this subsisting worry that ultimately revitalizes the uncles’ “Long distance sorrow” (that phrase from “Tiléfonos” seems pertinent here too). After all, Dionysus still fears the rawness of Thucydides’ one-sided account of “Greeks killing Greeks” nearly half a millennium after the Peloponnesian War ends (431–404 BC). This ancient agitation still registers in the Peloponnese today; the speaker hears the same anxiety in the “ancient, / anxious, broken English” of the “immigrant uncles,” who survived the Civil War but cannot express how the trauma of that experience has marked them.

These new poems continue to depict diasporic time and place in ways markedly similar to Kalogeris’s previous collections. Familial pasts, historical periods, and ancient eras disperse and fragment within lyric presents, the symbolic liminality of which is captured in the telephone cord that tangles, the refrigerator that ages, the vines that interweave, and the anxious speech that deteriorates. Guide to Greece also begins with mixed up lineages and anachronistic origins. Returning to Περιήγησις τῆς Ἑλλάδος (literally, Descriptions of Greece )—the second-century AD tour guide of the Asia Minor travel writer Pausanias—Kalogeris’s (2018) eponymous collection plays upon Pausanias’ ambiguous topographies of mainland “Hellas” in order to affirm that twentieth century “Greece” cannot be mapped according to fixed determinations (as the Population Exchange of 1923 attempted to do when it “repatriated” the two nations of Greece and Turkey):[12]

Endless genealogies, as densely entangled

As a grove of olive trees, his grasp of their roots

Extending all the way back to Epaminondas,

Who sprang from the earth of Thebes, before it was Thebes (5).

The poem’s speaker intentionally ascribes an impossible origin story to both general and city and ends with an impossible question, asking Pausanias himself “if perhaps you might have seen them, / My elderly parents somewhere in your travels” (6).

Kalogeris pays homage to those figures, real or imaginary, who have guided his poetic hand and shaped his discursive understanding of “home.” In this spirit, “Memorial Day” begins with a Greek Orthodox ceremony in a New England cemetery. Its list of remembered names drifts back into the Greek diasporas from which they came, like the ephemeral smoke of the vigil lamp. The poem roots itself in its familiar “Winthropic” scene, while reminding its reader that this home is built upon the remainders of many past homes, continuously scattered, lost, and remade throughout transnational Greek history:

Our people

Have lived in many places, our poets intone:

Egypt, Syria, Turkey… Even Kommagene,

That little kingdom snuffed out like a lamp.

There’s hardly a breath of air as the wisps of smoke

Unfurl on the listless breeze, and the names disperse.

Under the shade of the cypress trees, in Magna Graecia.

During a conversation with Kalogeris, I had the pleasure of hearing him read these final stanzas aloud. Afterwards, he explained to me that he wrote the third and second to last lines in pentameter but extended the last line to contain six metrical feet, evoking the Homeric hexameter. Expanding versification was his subtle way of transitioning from the living relatives commemorating their dead beneath the cypress trees to these departed souls traveling to the otherworldly “shade” of ancient myth. There, in what is now the coastal regions of Southern Italy, the cypress trees of Magna Graecia recall their namesake, Kyparissos, the young boy who grieved the stag that he did not mean to kill, until he was transformed into this tree symbolic of mourning. Topographical layers accumulate astounding resonance throughout Kalogeris’s trilogy. Readers will discover familiarity in estrangement when accompanying its speakers through the reimagined scenes of Guide to Greece, Winthropos, and Magna Graecia still to come.

Ilana Freedman

is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at Harvard

University. Her research explores comparative poetics, interdisciplinary

approaches to diaspora and transnationalism, and the study of classical

reception. Her publications include comparative readings of Nikos Gatsos,

Seamus Heaney, C. P. Cavafy, and James Merrill. She is currently the

graduate coordinator for the Modern Greek Studies Seminar and the Ludics

Seminar at the Mahindra Humanities Center, as well as the Graduate

Assistant for the Seminar on Cultural Politics: Interdisciplinary

Perspectives at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard

University.

Works Cited

Boynton, Owen. “(George Kalogeris) review of Guide to Greece.” Blogpost (09/01/19).

Cavafy, C. P., Edmund Keeley, Philip Sherrard, and George P. Savidis. Collected Poems: Bilingual Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Chouliaras, Yiorgos. Δρόμοι της μελάνης. Athens: Νεφέλη, 2005.

Euripides. The Bacchae. Translated by T. A. Buckley. Revised by Alex Sens. Further Revised by Gregory Nagy. Center for Hellenic Studies, 2020.

Hammer, Langdon. James Merrill Life and Art. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2015.

Heaney, Seamus. Death of a Naturalist. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Heaney, Seamus. North. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975.

Heaney, Seamus. The Haw Lantern: Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984.

Homer. Iliad. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Center for Hellenic Studies, 2020.

Hutton, William. Describing Greece: Landscape and Literature in the Periegesis of Pausanias. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Kalfopoulou, Adrianne. Passion Maps. Pasadena: Red Hen Press, 2009.

Kalfopoulou, Adrianne. A History of Too Much. Pasadena: Red Hen Press, 2018.

Kalogeris, George. Dialogos: Paired Poems in Translation. Los Angeles: Antilever Press, 2012.

Kalogeris, George. Guide to Greece. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2018.

Kalogeris, George. Winthropos. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2021.

Lambropoulos, Vassilis. “What is Transnational about Greek American Culture?” Erγon: Greek/American Arts and Letters , 17 February 2020.

Merrill, James. Collected Poems. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2001.

O’Connor, C. Hiatt. “A Word Slips Like a Drowning Hand: On the Poetry of N.C. Germanacos.” Erγ on: Greek/American Arts and Letters, 2 January 2021.

Papadopoulos, Stephanos. The Black Sea. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2012.

Papadopoulos, Stephanos and Peter Papathanasiou. “A conversation with Stephanos Papadopoulos & Peter Papathanasiou.” Poetry Interview in Tuck Magazine, 2017.

Rakopoulos, Theodoros. “Essay Review: The Poetics of Diaspora: Greek US Voices.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies, vol. 34 (2016): 159–65.

Ricks, Christopher (ed.). Joining Music with Reason: 34 Poets, British and American, Oxford 2004-2009 . United Kingdom: Waywiser, 2010.

Ricks, David. “ C. P. Cavafy: The Barbarians Arrive Today: Poems and Prose. Translated by Evan Jones (Review).” Translations and Literature, vol. 30 (2021): 390–96.

Seferis, George. Μέρες. Athens: Ίκαρος, 1975.

Stewart, Charles. “Forget Homi! Creolization, Omogéneia, and the Greek Diaspora.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, vol. 15, no. 1 (2006): 61–88.

Editor’s Note: On February 3, 2022, George Kalogeris gave an interview about “words and

places.” You can listen it here, or

read the transcript.

Notes

[1] In his review of the collection, Owen Boynton (2019) parses its enigma as “Hellas, that which is and is not Greece.”

[2] George Seferis’s (1975) phrase from his Μέρες ( Days) journals, which references the systematic traumas of the Asia Minor Disaster.

[3] In his essay “What is Transnational about Greek American Culture?” Vassilis Lambropoulos (2020) borrows Economou’s neologism to characterize “the creation and reconfiguration of Greek transnational identity,” which C. Hiatt O’Connor (2021) subsequently references in his review “A Word Slips Like a Drowning Hand: On the Poetry of N.C. Germanacos.”

[4] In “Forget Homi! Creolization, Omogéneia, and the Greek Diaspora,” Charles Stewart (2006) references this idealism surrounding the Greek state as an original “homeland” and the perceived “degradation” of Greek America (77).

[5] A play on the title of Cavafy’s poem “Να μείνει” (“Comes to rest”) (1919), in which an erotic encounter materializes in verse years after it occurs.

[6] Based upon a conversation with Kalogeris, who likely has in mind, among others, Heaney’s poems “Personal Helicon” fromDeath of a Naturalist (1966) and “Mossbawn” from North (1975).

[7] The bidirectional writing of ancient scripts, the etymology of which—“βοῦς” (“ox”) and “στροφή” (“turn”)—is prefigured in the practice of ancient ploughers, such as those depicted in the Iliad within the ekphrasis of the Shield of Achilles who “ἀροτῆρες ἐν αὐτῇ / ζεύγεα δινεύοντες ἐλάστρεον ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα” (“were working at the plough within [the field], / turning their oxen to and fro, furrow after furrow”) (Iliad 18: 543-549).

[8] Kalogeris’σ depiction of his grandfather moving to live with his son’s family in Winthrop after surviving the German Occupation relates to the second-generation diasporic Greek poet Adrianne Kalfopoulou’s poem “Neos Kosmos,” from her collection Passion Maps (2009). Its autobiographical speaker comparably “transcomposites” the impoverished scene of the contemporary neighborhood of Neos Kosmos in Athens with the devastations of the German Occupation through which her father lived before immigrating to America:

Discarded furniture’s piled high next to trash,

shattered bricks of a building going up in a too-narrow lot where

some young

family will move in with savings and a down payment on

possibilities.

Debris crunches under the wheels. I park and think of my father,

his home

in Athens taken by Nazi officers, then America’s plush interiors

that never managed to keep out what stayed in—I am most proud of that time

in the mountains. I was 16. There was no food in Athens. The

German officers

kept whatever there was for themselves

he repeated in rooms where he promised

books, a chance to eat at the table of plenty though I could not

eat what

he insisted I eat, as he tried to forget the dead by keeping us overfed (44).

Her father recalls the famine he experienced as a partisan fighter in the mountains, later overcompensating through his excess materialism in America. Through the association of the Athenian neighborhood during the Economic Crisis, Kalfopoulou emphasizes these manifestations of trauma and food insecurity as she remembers them growing up in her own household, where her father could never forget what had been taken from him and the ones whom he had lost decades before in Greece.

[9] “Frigidaire” approaches inherited trauma in a similar way to Stephanos Papadopoulos’s poem “Epilogue,” from his collection The Black Sea (2012).

I’m a name they never spoke, I stepped from the ashes

Blind, deaf and dumb to what they saw, still a witness

by some force that drags me toward these hills with nothing

but the shards of words passed on, the crumbling photographs,

the tears that slid from my father and grandfather

through the huge black eyes of paintings and into mine;

that weep when the light breaks on these imaginary cliffs (53).

The speaker is semi-autobiographical—Papadopoulos, a Greek American poet born in North Carolina in 1976 and then raised between Paris and Athens. The Black Sea (2012), his collection based upon his family’s ancestral connection to Asia Minor, is the product of his motorbike tour from Athens to the southern coast of the Black Sea nearly a century after the Asia Minor Disaster. Papadopoulos undertook the journey because he realized that the actual landscape of this “inherited memory of war” was not known to him as its descendent (Papadopoulos and Rossoglou). “Still a witness” by birthright, the speaker of “Epilogue” feels drawn to the sites of material devastation and the traces of ghosts that linger in the Pontus. Familial tears trickle from relatives’ portraiture-eyes to those of the speaker, intertwining the “progressive scene” of an American university town with those Black Sea ridges of the speaker’s heritage (53).

[10] The History of the Peloponnesian War is the English language title of Thucydides’ histories, which are referred to by their opening words in ancient Greek.

[11] Kalogeris translates Cavafy’s poem in Winthropos, rendering as its final lines “But those two gallant horses kept right on weeping, / Weeping for Patroclus, as if there was no end to what they felt” (2021, 54).

[12] Pausanias claims to cover “πάντα τὰ Ἑλληνικά” (“all things Greek”), an exhaustive morphology that proves tricky since he himself holds “no fixed idea at all as to what constitutes Hellas” under the ancient period of the Pax Romana (Roman Peace) (Hutton 2005, 61).