The Hyphenated Hyphen: Turkish-in-the-Greek-Script American Literature

By Will Stroebel

Abstract

This essay is a call to action. It addresses the experience of (and is addressed to the descendants of) Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans. As I write in the final section, its ultimate purpose is to function as the starting point for a larger public dialogue over the role of the Turkish language in Greek America and to connect with as many descendants of Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox migrants and refugees as possible. Together, I invite them to collectively digitize and curate the textual artifacts of their grandparents and great-grandparents. Buttressing this call to action is a historical argument about the media exclusion and cultural barriers faced in early-twentieth-century America by those Greek-Orthodox Christians whose primary language was neither Greek nor English—and, in the face of such barriers, what kinds of media and literature these communities generated. I spend the first section of the essay briefly tracing out the larger media landscape in the early twentieth-century United States, placing my study in dialogue with Randolph Bourne. I examine the transnational print networks tying immigrant groups together both within and beyond North America and, subsequently, the ideological pressures of the Anglophone “echo chamber” and media consolidation that began to reach full force during World War I; these pressures were felt and replicated by the Greek American population itself, with sometimes detrimental repercussions for some segments of the population. Following this overview, I introduce the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox community and attempt to paint an initial picture of their cultural experience in the United States. I conclude, as noted above, with a call to gather up and preserve the precious cultural heritage of this community.

Do you identify yourself or your ancestors as part of the Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox community? Please share this essay with your parents, grandparents, cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends and contact the author of this essay (stroebel@gmail.com).

What was the experience of Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans in early twentieth-century America? What did it mean to be a “double” minority—a minority within a minority—during this period? What kinds of stories did they tell one another, how did they share these stories, and what kinds of discrimination did they face in doing so?

Over the past two years, I have been working to piece one of these stories together, chasing after a handful of Turkish-language poems, ballads, and novels written in the Greek script. They were put to paper in the United States between the 1920s and 1940s, the literary products of a refugee from Asia Minor, yet they continued to be used and circulated by other Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox readers for decades afterward—up to and beyond the 1970s—in a wide geographic swath that reached from the Midwestern United States to the Eastern Mediterranean.

It is the voices of these particular books—Turkish inscribed in Greek letters—that first brought me to the topic. Nevertheless, they are neither the subject nor the focus of the current essay. My primary aim in writing these words is to reach out to you, the readers of the Greek diaspora, and to hear your own voices. Generating an open discussion on the importance of the Turkish language within certain pasts and parts of Greek America, I hope to hear your own perspectives and to invite your collaboration. In my conclusion, I offer concrete and explicit suggestions as to how readers like you, your family, friends, and I might collectively work together to assemble a stronger, more diverse picture of the Turkish-speaking Greek American past: a collective digital library. If you’re curious (or impatient), I encourage you to jump ahead now and read the final section or two, beginning with “Turkish-in-the-Greek-Script American Literature” and “A Call to Action for my Readers.”

Before I myself get to those sections, however, I want first to paint a larger, darker picture of the media and political landscape in which Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans lived, wrote, and read. As a “hyphenated-hyphen,” the Turkish language of Greek-Orthodox Americans was faced with the assimilationist pressures of both Greek- and English-language media during the first half of the twentieth century. In other words, not only was their Turkish foreign to the English language of the majority but, perhaps even more importantly, to the Greek language of their fellow Greek Orthodox Christians. Discrimination, exclusion, and the power struggles of elites are an important part of the history I examine here. Indeed, these struggles continue to shape our communal discourse even today. Therefore, as I’ll reiterate in my concluding section, the stories of Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans have an important role to play in the current moment. They don’t simply reshape our understanding of the past but, in doing so, inform our engagement with the present. [i] As a double minority or a “hyphenated hyphen,” Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans offer an important object lesson in belonging and connectivity. Simultaneously, their experience might warn us against the dangers of consolidation (i.e., the concentration and unification of plural entities into a solid, single body) on at least three fronts:

1. Consolidation of state power

2. Consolidation of media

3. Consolidation of community identity.

All three of these forms of consolidation are interrelated, as I’ll try to describe in what follows. All three have likewise wrought deleterious effects on both cultural and political discourse in the United States over the past century. In seeking out the stories of those like the early Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Americans, therefore, we are simultaneously seeking out a means to “decluster” our society: the means by which we might achieve a more decentralized and democratic method of governance, media production, and community building.

I begin this process of declustering not with the Turcophone Greek-Orthodox themselves but with a young, Anglo-Saxon writer named Randolph Bourne. Following his trajectory, we can better understand the America that awaited our own immigrants.

America: A Transnational Confederation?

Just over a century ago, in the spring of 1916, Randolph Bourne was laboring over the draft of a new essay: “Trans-national America.” Published later that summer in The Atlantic Monthly, Bourne’s essay invited readers to survey a startling new vision of the United States, one whose foundational metaphor was no longer the melting pot, with its implicit work of liquefaction and homogenization, but instead a vast loom. America was becoming, he wrote, “a weaving back and forth, with the other lands, of many threads of all sizes and colors” (96). [ii] Rather than submitting themselves to dissolution within a melting pot (only to be poured into a prefabricated mold), Bourne recognized that immigrants insisted instead on maintaining their connections abroad, weaving them together with those of other communities within the United States to generate a collective Americanism.

True, the essay was not without its blind spots: Bourne’s transnational vision was limited, for example, to immigrants from Europe; even more important, no mention was made of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, nor of American settler colonialism and the vast network of ethnic cleansings and genocides [iii] that had made Bourne’s transnational tapestry possible in the first place. Having filled in these gaps, however, one can only admire the overall picture: a daringly prescient analysis and the critiques that it leveled against the militant assimilationism of the dominant Anglo-Saxon class of the time.

The power of Bourne’s vision derived primarily from an apparent contradiction. Surveying immigrant communities, he was among the first to note their tendency, “as they became more and more firmly established and more and more prosperous, to cultivate more and more assiduously the literatures and cultural traditions of their homelands. Assimilation, in other words, instead of washing out the memories of Europe [sic], made them more and more intensely real” (86). In a seeming paradox, Bourne emphasized that it was through the process of assimilation that migrants maintained—indeed, heightened—their dissimilarities, developing their own distinct cultural “nuclei” (this is Bourne’s word). Having integrated themselves into local economies, they founded non-English-language schools and printing presses. Doing so, these immigrants were stringing together a “cosmopolitan confederation of national colonies, of foreign cultures.”

This confederation, “inextricably mingled, yet not homogeneous,” was to live or die by the single most precious lifeblood circulating through its veins: print media. It was through the newspapers, journals, chapbooks, and books of these non-English American printing presses that immigrant communities could maintain their connections both across cities within the United States and abroad, weaving together a transnational network. Patricia Okker notes: “That these periodicals were minority publications actually increases the importance of circulation. Unlike, say, a local newspaper that is sustainable within a very localized community, many of these periodicals were required to circulate beyond local borders if they were to survive” (2012, 7).

Certainly, one of the critical functions of non-English-language print media was to bind together a given local community within a given U.S. city. Yet if these publishing ventures were to avoid folding within a matter of months, they also needed to weave their local base into other homoglot readerships across territories and oceans. It was because of the startlingly decentered nature of these publications, for example, that the first issue of the Greek-language journal Ἡ Σύγχρονη Σκέψη: Πανελλήνια Ἐπιθεώρηση (Modern Thought: Panhellenic Review), published in Chicago, could carry an advertisement for Ἄγων, a Greek-language publishing house across the ocean—not in Athens but in Paris—praising its books as “rivaling the best European editions” («ἀμιλλώμεν[α] μὲ τὰς καλλιτέρας εὐρωπαϊκὰς ἐκδόσεις») and noting that “all books are shipped upon reception of a wire transfer equivalent to their sales price plus postage” («Ὅλα τὰ βιβλία ἀποστέλλονται ἔναντι ἐμβάσματος τοῦ ἀντιτίμου των καὶ ἐπὶ πλέον τὰ ταχυδρομικά»). There was, in other words, a kind of redoubled amplification of transnational media, in which one node (Chicago) gestured toward another node (Paris), making explicit to its readers (who were located in any number of nodes across the earth) the means by which they could be brought together: nothing more than a wire transfer and postage. In the second issue, the editors noted with a mixture of surprise and pride that their subscription base lay not only within the United States nor even in Greece but was spread across the strongest pockets of the Greek world. Σύγχρονη Σκέψη, they wrote, “was received with greater enthusiasm in those places where we were expecting it less, ... particularly in Egypt, in Istanbul, in Greece” («ἔγινε δεχτὴ μὲ μεγαλείτερο ἐνθουσιασμὸ στὰ μέρη ἐκεῖνα ποὺ δὲν περιμέναμε καὶ τόσο..., ἰδίως στὴν Αἴγυπτο, Πόλη, Ἑλλάδα»). This is but one example of the hundreds of integrated yet distinct threads within Bourne’s loom, running across the warp and woof of the country and beyond. Surveying the larger picture, Bourne saw a media network in which no single ethnic thread could claim hierarchical predominance or shape the larger narrative. America, he wrote, “shall be what the immigrant will have a hand in making it, and not what a ruling class, descendant of those British stocks which were the first permanent immigrants, decide that America shall be made” (87).

The closer one inspected Bourne’s American tapestry, the more profoundly one’s sense of center and periphery was unsettled. Indeed, his insistence on decentralization is perhaps the most fundamental challenge to the American status quo today, a challenge whose repercussions are not just cultural but, as I’ll discuss below, political as well. The notion that a handful of Anglo-Saxon newspapers, journals and books constituted the center of American culture, entertainment, and political debate seemed somehow misguided when observed from the perspective of Bourne’s myriad “threads” and the hands that shuttled them back and forth across this landscape. Indeed, as Bourne wrote, it was mainstream American popular culture that constituted a dangerous “fringe”—one that threatened the soundness of these “decentered centers” and their larger American loom:

The influences at the center of the nuclei are centripetal. They make for the intelligence and the social values which mean an enhancement of life. And just because the foreign-born retains this expressiveness is he likely to be a better citizen of the American community. The influences at the fringe, however, are centrifugal, anarchical. They make for detached fragments of peoples. Those who came to find liberty achieve only license. They become the flotsam and jetsam of American life, the downward undertow of our civilization with its leering cheapness and falseness of taste and spiritual outlook, the absence of mind and sincere feeling which we see in our slovenly towns, our vapid moving pictures [and] our popular novels. (91)

Today, for most readers, the spatial metaphor here is counterintuitive: what Bourne calls the “fringe” is actually what we would today identify as mainstream popular culture: the “vapid moving pictures” and “popular novels” that few in the twenty-first century would place at the fringe of American cultural production. Granted, the fact that this industry was yet in its earliest nascence circa 1916 may help in part to explain Bourne’s vision, but it doesn’t excuse his shortsightedness. Indeed, while Bourne attributes the “vice” of cheap pulp fiction exclusively to English-language print, even a cursory glance at the larger American tapestry reveals that non-English-language counterparts boasted their own cheap serials and popular titles as well. Nor was this cheap literature necessarily a problem in and of itself, as later cultural theorists (beginning with Richard Hogartt [iv]) would argue. The real problem was one that Bourne would only come to identify later, in hindsight: media consolidation and the narrowing of public discourse that accompanies it. In other words, the evil with Bourne’s “fringe” was not so much its aesthetic crudeness but its swift consolidation into a new and unprecedented center of gravity. Indeed, among this group we must count not only popular entertainment but many of the intellectual journals for which Bourne and his own acquaintances wrote. These journals were no less invested in consolidating the public discourse during those early summer days of 1916.

Bourne could hardly have been oblivious to the media hierarchies at play. In 1916, an idea like “Trans-national America” could get a person into trouble. However many threads Bourne may have identified crisscrossing America and the two oceans bordering it, it was a plain and simple fact that, within the publishing world, not all these threads were created equal. Bourne’s own editor at Atlantic Monthly, Ellery Sedgwick, was aghast at the essay’s message. After reading the draft, he replied to Bourne in the following terms:

[Y]ou speak ... as though the last immigrant should have as great an effect upon the determination of our history as the first band of Englishmen who ever stepped on our coast.... What have we to learn of the institution of democracy from the Huns, the Poles, the Slavs?... For you to speak as though the New Englander of so-called pure descent and the Czech were equally characteristic of America seems to me utterly mistaken.

Despite his unapologetic waspishness, Sedgwick nonetheless went on to publish the essay—“to his everlasting credit,” as Jeremy McCarter writes. [v] It was a demonstration that, at least in certain editorial circles of what Bourne called the “significant class,” dissenting voices were still valued. But the approaching thunderclouds of militarism were about to upend everything. Within a year, the United States entered the First World War. Doing so, the state definitively put the country on a trajectory of imperialist interventionism, media censorship, and political witch hunt from which it has never fully escaped. Needless to say, those invested in mobilization and consolidation for the war effort began a campaign to sever as many transnational “threads” as they deemed necessary.

True, the witch hunt reserved its greatest wrath for industrial unionists, socialists, communists, and anarchists, those whose activities threatened most directly the moneyed class and the federal war effort to which it had attached itself. [vi] Yet the persecution also fell full bore upon the backs of “hyphenated Americans,” those who tied their identity not only to America but to some nation abroad. These so-called hyphenated Americans, whom Bourne had celebrated in his essay less than a year earlier (when such ideas could at least be uttered without the threat of tar and feathers), were now the target of, among other things: jingoist hate speech, mob violence, federal surveillance and incarceration, and deportation. A century later, these same problems are urgently familiar to us, as even a cursory glance at the news indicates. Indeed, many of the same titles that we recognize today as part of the mainstream media discourse were blithely engaging in this brutal witch hunt a century ago. The Wall Street Journal, for example, was relentless in its militant support of jingoism and war. While it threatened antiwar activists with outright mob violence, to foreign-born Americans and immigrants it offered the more comforting promise of an internment camp: “Every enemy alien at large offsets a soldier at the front. Put them behind barbed wire—every last one of them,” the editor sanguinely wrote in a column whose apparently unironic title was “The Road To Peace” (Nov. 23 1917).

Mainstream press was not the only force driving this assault. Eventually, President Wilson himself adopted the same language. In his last speech before the fateful congressional vote on the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson railed against Bourne’s Transnational Americans in terms no less violent (though more eloquent and thus more dangerous) than those of a common mob: “And I want to say—I cannot say it too often—any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this republic whenever he gets ready.” Such words, Wilson continued, were not idle observations; they reflected policy on the ground: “If I can catch any man with a hyphen in this great contest, I will know that I have caught an enemy of the republic.” Boasting the presidential seal of approval, this racist nativism went on to metastasize in the following decades, casting its cancerous spores into fields ranging from university knowledge production (e.g., eugenics [vii]) to congressional policy (e.g., The Immigration Act of 1924).

How had it come to this? Just a year after Bourne’s “Trans-national America,” how had the United States entered the most destructive and pointless war in history—despite “the manifest indifference or reluctance of the majority of its population,” as one pro-war editorial [viii] bragged? How had it begun attacking and silencing its “hyphens” with such rancor? How had public discourse been transformed so quickly and so radically?

Bourne quickly developed his own answer, placing the blame on his erstwhile colleagues and companions: intellectuals. They were, after all, the backbone of America’s newsprint and periodical production and the ringmasters of public discourse. “The War and the Intellectuals,” printed in the influential The Seven Arts in the summer of 1917, constituted an open attack on America’s liberal intelligentsia: “The war sentiment, begun so gradually but so perseveringly by the preparedness advocates who came from the ranks of big business, caught hold of one after another of the intellectual groups.... The intellectuals, in other words, have identified themselves with the least democratic forces in American life.” If the vast majority of the Anglophone American intelligentsia had looked upon the outbreak of war with abject horror and rejected it, over the course of only two years an equally vast majority reversed course and began dancing to a new tune. They were, in effect, using their platforms in the media to provide the sparkling intellectual justifications for what was really, in John Reed’s words, little more than a “traders’ war.” [ix]

Writing a decade before Antonio Gramsci, Bourne had placed his finger on the problematic allegiances of “professional” (or “traditional”) intellectuals: “One of the most important characteristics of any group that is developing towards dominance,” Gramsci later wrote, “is its struggle to assimilate and to conquer ‘ideologically’ the traditional intellectuals” (2007, 10). Coupled with moneyed interests and increasingly powerful publishing titles, these intellectuals were assembling the so-called echo chamber of the corporate media landscape that we know too well today. [x]

The consolidated collusion between media intellectuals and the state was often explicit, and they worked together to utterly destroy the metaphor of the loom, returning with violent force to the melting pot. This was nowhere clearer than in the words of George Creel, an erstwhile journalist whom Wilson appointed to head the federal government’s first modern propaganda agency, the Committee on Public Information (CPI). In a now-famous metaphor, he signaled something close to a militarized melting pot, stating that the agency’s goal was to “weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct.” Consolidation, in other words, in its most violent form. This white-hot mass instinct would soon scald Bourne’s hand, who continued throughout that summer to send off his antiwar missives to The Seven Arts, which faithfully published them. Yet before year’s end, the journal’s patron revoked her support. Stung by its antiwar agitation, she shuttered The Seven Arts before it had finished its second year of life. Bourne had already foreseen it all: “Be with us, they call, or be negligible, irrelevant. Dissenters are already excommunicated. Irreconcilable radicals, wringing their hands among the debris, become the most despicable and impotent of men.” Bourne was not the only victim. Anyone who dared to write against the war and the targeting of “hyphenated” America as internal enemies soon found themselves without a byline; if they dared to continue their speeches on a soapbox, they risked a lynching. [xi] Writing to a friend, Bourne bitterly complained, “I seem to disagree on the war with every rational and benevolent person I meet.... I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times, except perhaps with the Bolsheviki. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts seem unprintable” (Clayton 1984:230).

Within this emerging landscape, it was not unlikely that many non-English or “hyphenated” media platforms chose silence or, indeed, explicitly adopted the message and tone of the majority. Yiorgos Anagnostou observes that, “[o]ften mediated by native elites, the politics of immigrant belonging resemble an anthropological hall of mirrors..., from which point it is possible [for immigrants] to reflect and deliberate on strategic positioning. Subjected to the gaze of the dominant, immigrants set up a system of counter-surveillance” (2003, 297). The goal of such surveillance, then, is expressly the ability to mimic and assimilate the dominant narratives of the center and to silence or eliminate any voices within the community that might diverge from them. This was a lesson hammered home violently among foreign-born American communities in the years immediately before and following the end of the First World War—and a lesson that has lasted till today. [xii]

Above, I noted that the strength of Bourne’s transnational America lay in its decentralization. By now, it should be clear that the stakes of this decentralization were not only cultural but political in nature. A healthy political discourse was impossible in a United States in which policy discussions were monopolized by a centralized conglomeration of Anglo-Saxon media—a conglomeration from which, as if by smelting, the dominant classes melted away and discarded anything deemed base. This pattern of conglomeration was not unique to media, of course; it was all intricately connected, extending to every aspect of the social order, from the economy to statecraft. Indeed, Bourne now argued that such consolidation was synonymous with the state itself.

He had been developing this argument in what became his final, unfinished essay, “The State,” cut short by his untimely death at the outbreak of the Spanish Influenza. The essay began by marking a differentiation between the “nation” and the “State” of nation-state. While he understood the former as a “loose population spreading over a certain geographic portion of the earth’s surface,” the latter was essentially not an object but a process—a work of alchemy or a sleight of hand by which an initially “arbitrary usurpation, a perfectly apparent use of unjustified force,” might be converted into the status quo, “the taken for granted.” For Bourne, the State was a massive parlor trick, played upon the nation. “[W]e have the misfortune of being born not only into a country but into a State, and as we grow up we learn to mingle the two feelings into a hopeless confusion.” The confusion lay primarily in our inability to comprehend the State as an object and thus our constant recourse to metonymy: State as nation, State as country, State as government. In contradistinction to governance, however, which presents itself in concrete forms, such as that of a school board or a city council—i.e., in narrow constellations that can be surveyed and grasped in total—the State was, for Bourne, difficult to conceive as a whole; it remained a “mystical conception” whose primary function was the consolidation of power, a “repository of force” at the service of the “significant classes.” The question was how to draw the masses of the nation into mental and physical alignment with that force.

For Bourne, writing in 1918, the answer had been deafening: war. “War,” he famously wrote, “is the health of the State.” It was through war that dissenting or minority opinions, which had previously been tolerated as a minor though lawful “irritant,” became a cardinal sin within the cultural field and a felony within the legal field. “Public opinion, as expressed in the newspapers, the pulpits and the schools, becomes one solid block.... The leaders of the significant classes, who feel most intensely this State-compulsion, demand a one hundred per cent Americanism, among one hundred per cent of the population. The State is a jealous God and will brook no rivals.” In other words, war was the method by which a constellation of otherwise indifferent or recalcitrant communities could be herded into physical if not mental alignment with the state (or, if they refused, they could be removed from the picture). Under perfect conditions, the nation would go so far as to imagine itself to have declared war—when in fact, Bourne averred, nations do not—cannot—make wars. War demands consolidation and centralization:

Nations organized for internal administration, nations organized as a federation of free communities, nations organized in any way except that of a political centralization ... could not possibly make war upon each other. They would not only have no motive for conflict, but they would be unable to muster the concentrated force to make war effective.

Looking back from the precipice of 1918, Bourne’s Transnational America of 1916 now took on a new light: his celebration of a “cosmopolitan confederation” of foreign communities was not limited to the cultural plane, nor was it mere identity politics for the sake of identity politics: it was a real political vision built upon a radical concept of decentralization, a loosely strung-together federation of transnational communities and cities. A vision that was strangled in its cradle. [xiii]

While Bourne’s Transnational America may have survived the First World War, the illusion that it existed in a power vacuum—or, indeed, in a democratic confederation—had been shattered.

Pluralizing the Greek American Experience

Bourne’s vision was not the only thing shattered by the war. Half a world away, the Ottoman Empire was about to be smashed to pieces. Here, World War I had given way not to a weary peace but to occupation and a second round of conflict. The Armistice of Mudros in October 1918 marked an end to official hostilities between the Entente and the Ottoman Empire, yet it contained a vague and broad provision that, in case of unrest within Ottoman territories, the Entente maintained a right to intervene with military occupation. Without this provision, the history of the region would likely have been markedly different.

A few months later the British PM Lloyd George cited a report of Turkish guerillas in the region of Izmir, using it to open the doors for the Kingdom of Greece to occupy the city and its surrounding hinterland. [xiv] The results of this occupation were a long and bloody conflict known today as the Greco-Turkish War—one that saw multiple atrocities and acts of ethnic cleansing on both sides. It devolved into something close to a brutal civil war, often aided by local guerilla units of various communities who had old accounts to settle. At the end of the war in 1923, the two states agreed to a “Population Exchange,” a petty euphemism for another round of ethnic cleansing. Diplomacy finished up what guns and swords had failed to achieve alone, on a scale that had rarely been seen in human history: Turkey was to deport over one million Greek-Orthodox Christians from its territories, while Greece was to deport nearly half a million Sunni Muslims from its own, shuffling tens of thousands of families across the Aegean like a deck of cards—fall where they may. A number of the Greek-Orthodox refugees uprooted from Anatolia continued their journeys westward, to the United States, where a sizable portion of Orthodox Anatolians had already settled over the previous two decades of transatlantic labor migration. [xv]

Notice my deliberate use of the term “Orthodox Anatolian.” It’s a historical fact that, just as many of the supposed Turks uprooted from Greece spoke no Turkish, many of the supposed Greeks uprooted from Turkey spoke no Greek. True, there were many Anatolian Greeks with a degree of proficiency in both languages, but there were also hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Christians who spoke only or primarily Turkish. They wrote it with the alphabet of their holy book, i.e., Greek. They were what most now call the “Karamanli” community, and they stumbled sharply over the two axes of national identity—language and religion—in a region where such contradictions were becoming inexcusable. For while their religion and alphabet drew them into the orbit of Greek sentiment, their language was that of the (since 1917 official) “enemy” of the Greek state. On the other hand, despite the language and customs that they shared with Sunni Turks, their religious differences constituted an increasingly insurmountable institutional barrier as ethnic tensions rose in the final decades of the Ottoman Empire.

Who were these Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Christians? With whom did they identify? Were they for us or against us? In those final Ottoman years, Greek and Turkish nationalists scrambled to answer these questions each in their own way, yet both did so through the same logic: Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians were to be defined not by their present condition but through their historical origin. Greek and Turkish nationalists were driven by what Jacques Derrida has famously called a “fever”: a burning passion for an authentic, singular origin. Turcophone Orthodox Christians were Byzantine Greeks—so argued Greek nationalists—and they had spoken Greek for centuries; it was only the long and dark isolation of Ottoman rule that had driven them to adopt the language of their Turkish neighbors. No—Turkish nationalists countered—the Karamanlides had always been Turkish; they were among the first waves of Turkish migrants into the territory of Byzantium, well before the rise of the Ottoman state, and had adopted the religion of their Greek neighbors. Ultimately, both Greek and Turkish nationalists were hoping to reach what Derrida calls the “moment of ecstasy,” when their argument became so transparently obvious that the origin might “speak by itself” (58). They rarely thought, however, to let the Turcophone Christians speak by themselves. It’s only through the work of more recent scholars, none more tireless than Evangelia Balta, that they have been allowed to speak for themselves at last.

The truth of the matter was that, over the course of the nineteenth century, Turcophone Greek-Orthodox Christians had been assiduously developing their own print media. While they were understandably dwarfed in size by Greek and Ottoman-Turkish publishing networks, a number of Karamanli newspapers, journals, and book-length translations and adaptations of modern fiction had been circulating in the Eastern Mediterranean for decades. In a careful survey of these media, Balta concludes, “The overwhelming majority of the authors and translators of Karamanli works call their reading public ... ‘Christians,’ ‘Orthodox Christians,’ ‘Christians of Anatolia,’ ‘Orthodox Christians of Anatolia,’” explicitly avoiding the term Greek (2010:63). These Turcophone Rum offered their definitive allegiance neither to Greece nor Turkish nationalism but drew substantially from the cultural traditions claimed by both. As just one example, while their novels were primarily translations and adaptations from Greek and French sources, their poetry moved in the traditional Turkic forms known best to the ozan and aşık minstrels of Anatolia. In a way that perhaps only Randolph Bourne might have recognized and applauded at the time, the Karamanlides were creating their own cultural tapestry: “a weaving back and forth” across Anatolia and the Aegean, creating a stateless network “of many threads of all sizes and colors.”

The Population Exchange placed this “transnational weaving” in grave danger. When, in 1925, the Karamanlides were forcibly uprooted from their homes and marched westward to Greece, it was only a matter of time before their print media collapsed. While they had managed to begin circulating a newspaper in Athens—Προσφυγική Φωνή / Μουχατζήρ Σέδαση (The Voice of the Refugee)—it was soon attacked by the mainstream Greek-language press and folded the next year. [xvi] Why? What was the problem with speaking or printing Turkish in the streets of Greece? Randolph Bourne had already answered these questions less than a decade earlier, in words that I cannot help but place in bold: “Anything pertaining to the enemy becomes taboo. His books are suppressed wherever possible, his language is forbidden. His artistic products are considered to convey in the subtlest spiritual way taints of vast poison to the soul that permits itself to enjoy them.” To the bourgeois elite of Greek society, the Karamanlides were an uncanny specter of the national “enemy,” haunting the streets of Greece and the pages of its print with a language and culture whose poisons it was imperative that they staunch. In Greece, state and nation seemed to have fused together into a “white-hot mass instinct,” tearing out the Turkish threads from of its cultural tapestry. The Karamanlides’ newspaper folded within two years, never to be replaced. Within a decade, Karamanli print had died and its multi-colored weaving had begun to unravel in Greece, where the Karamanlides themselves existed in limbo as second-class Greeks.

What happened, however, when this Turcophone Greek Orthodox “weaving” was transplanted to the United States? To my knowledge, no research has yet been carried out specifically on the Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox immigrants to the United States and, as a result, I don’t yet feel comfortable speaking with any certainty of their collective experience. To provide a backdrop, however, one might begin by looking at the larger picture of Greek-Orthodox migration during the period. Crucially, local and regional networks were far more important for early, working-class immigrants than national identities or the organizations that represented them. In other words, building connections with others from your village or your prefecture were far more important than any solidarity that you supposedly owed to the Greek State or the Panhellenic Unity (Πανελλήνιος Ένωσις) that represented it. Yannis Papadopoulos writes that migrants, “at least during their first years in the United States, functioned within a frame that was more trans-local than trans-national,” such that “it was by no means a given that immigrants from different regions of the Greek state or the Ottoman Empire would feel solidarity to one another” (2013, 221-22). As the labor historian Dan Georgakas has noted, working-class immigrants “would often go hundreds of miles to support strikers from the same villages or region” (1996, 212). The same could hardly be said for their support of the Greek state, which most of them viewed with deep suspicion if not hostility (Papadopoulos 2013, 221). In the years leading up to the First World War, the Greek state certainly hadn’t helped matters, clumsily attempting to implement an immigrant residence tax (διαμονητήριο τέλος) and chasing after draft-age male immigrants in an attempt to force them to return to Greece and serve in the military—with threats of confiscation of family property in Greece or deportation of relatives (228). Such strategies deeply alienated early working-class immigrants and only further entrenched their connections to immediate community—which may not necessarily have coincided with any notion of “Greekness.” Indeed, one scholar researching the early migration networks of Sunni Turks has concluded that it was Greek-Orthodox neighbors and friends who served as their primary sponsors and companions. [xvii] The solidarities that these peasants and laborers built with fellow villagers—both within and across religious and linguistic boundaries—deserves a larger place in the narratives of Greek American identity today.

As Anagnostou has demonstrated, the generic, one-size-fits-all “Hellenic-American” identity that has come to dominate mainstream media representations today was built not by the early majority of immigrants themselves but by later organizations like AHEPA: The American Hellenic Progressive Association, which had succeeded the earlier Πανελλήνιος Ένωσις as the primary organ of Greek Americanism. It was an identity, we should recall, that was forged during a tense political period of growing anticommunist hysteria and a racism that targeted most forms of hyphenation—save for those that began with “Anglo.” Within this space, which Anagnostou described above as a “hall of mirrors,” well-to-do Greek Americans and many small business owners tacitly accepted or adopted behaviors similar to those of the Anglo-elite in order to lay claim to whiteness. Anagnostou suggests that when observed under the historian’s microscope, whiteness thus becomes “a process of contextual negotiation and oppression, in which certain ethnic ‘options’ become available or privileged (or, more precisely, are produced as options) while others are displaced, stigmatized, or even eliminated” (2009, 28). If particular hyphenated identities beyond northern Europe, like Greek American, have today attained the category of whiteness, they have done so only through a mobility that was gained through the express exclusion of certain members whose speech or politics did not align with the desired image. For example, writing just a year before the deeply racist Immigration Act of 1924 (which targeted Greeks, among others), Serapheim Canoutas bemoaned:

Ἂς μὴ λησμονῶμεν, ὅτι, ἂν ὑπάρχουν μερικαὶ χιλιάδες πράγματι φιλοπρόοδοι καὶ καλῶς ἀποκατεστημένοι Ἕλληνες ἐν Ἀμερικῇ, οἱ ὁποῖοι πράγματι τιμοῦν τὸ ἑλληνικὸν ὄνομα, ὑπάρχουν πολὺ περισσότεροι φυτοζωοῦντες, καὶ οὺκ ὀλίγοι οἱ ὁποῖοι προσβάλλουν τὸ καλὸν ὄνομα τῶν φιλησύχων καὶ προοδευτικῶν. Ὅτι ἡ χαρτοπαιξία καὶ ἡ ἐγκληματικότης ὁλονὲν αὐξάνει, ἀντὶ νὰ περιορισθῇ, ὁ ἀμφιβάλλων δὲν ἔχει παρὰ νὰ ρίψῃ ἑνα βλέμμα εἰς τὰς Ἑλληνικὰς ἐφημερίδας τῶν τελευταίων μηνῶν. Κατὰ πληροφορίας ἐκ διαφόρων Πολιτειῶν, καὶ ἰδίως ἐκ τῶν Νοτίων, Ἕλληνες διατάσσονται ὑπὸ τῶν Κοὺ-Κλοὺξ-Κλὰν νὰ ἐγκαταλείψουν διαφόρους πόλεις. Μερικοὶ ἐκακοποιήθησαν, ἄλλων τὰ μαγαζιὰ ἐμποϋκοταρίσθησαν.

Let’s not forget that if there are a few thousand progress-loving and well-to-do Greeks [φιλοπρόοδοι και καλώς αποκατεστημένοι Έλληνες] in America, who indeed honor the Greek name, there are many more dirt-poor lowlifes [φυτοζωούντες], not a few of whom tarnish the good name of those of us who are peaceable and progressive. Anyone who doubts that card-playing and criminality are on the rise, rather than falling, has only to glance at the Greek press over the past months. According to information from various states, particularly those in the south, Greeks have been ordered by the KKK to abandon various cities. Some are assaulted, while the shops of others are boycotted. [xviii]

Differentiating two classes—the progressive, “well-to-do” Greeks and the working-poor Greeks—Canoutas implicitly blamed the latter for the fact that the former (along with their businesses) were the targets of the KKK and white nationalists. While 1923 was an early phase in this process, eventually it came to pass that qualities such as poverty or political radicalism, as Anagnostou writes, “meant exile from whiteness” (2009, 206). Class and race were inextricably bound together for immigrant communities, a phenomenon that was institutionalized in the ensuing decades by Hoover’s FBI, which infused racial politics into its files on leftists. While some Greek Americans, like Johnny Otis, openly chose to identify as black, others, such as Alexander Karanikas’s family, were cast out of whiteness for their progressive political convictions. [xix] The stories of these “banished” Greek Americans were silenced and buried—but not erased. Scholars such as Dan Georgakas, Yiorgos Anagnostou, or Kostis Karpozilos, among others, [xx] have begun to excavate these stories and their intersections, yet one dynamic remains in need of attention: language.

When Anagnostou writes that “bilingualism was seen as anathema and a menace to the nation” (2009, 10), the nation to which he refers is the Anglo-Saxon-dominated United States and the bilingualism is that which holds between two national languages (Greek and English). But what happens when we turn this observation on its head and examine the inner workings of the Greek American community itself, through the lens of the Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians? In such a case, the dominant nation becomes “Greek” and the language that menaces it is the Turkish of Anatolian Orthodox migrants and refugees, a minority language cast adrift by the violence of the State, with no official organs to sponsor or protect it. It was a minority within a minority. And it was subjected to a similar stigma at the hands of that minority’s ruling majority. Yannis Papadopoulos writes that the Greek American ruling class “played a role in the expurgation of non-Greek-speaking Orthodox Greeks and, later, working-class Greek Americans from the Greek communities” (2008, 197). The categories of language, ethnicity, and class were deeply intertwined: “Members of the working class were characterized as Albanian, Bulgarian, or Turks” (ibid., 197). Indeed, Papadopoulos writes that it was not uncommon for Orthodox immigrants from Anatolia to “clash” with those from Greece (2013, 222). In the early months of 1916, for example, just as Bourne was drafting his visionary “Trans-National America,” Anatolian immigrants in Springfield Massachusetts were snubbed during the appointment of their church’s new priest, having been ostracized as “Turks” (2008, 286-87).

Given this picture, we can now point to a second blind spot in Bourne’s Transnational America: built upon the problematic category of “nations,” it largely depended upon the relatively clean and homogenous nature of any given immigrant community’s linguistic and ethnic unity. Up to the end of his life, Bourne still maintained this unhelpful oversimplification regarding “national” communities. While he clearly understood the dangers of a homogenized and consolidated state (e.g., the United States), his writing demonstrated little awareness that a given community within that state (e.g., Greek Americans) might mirror the same dangerous tendencies toward homogenization and consolidation—indeed, in “The State” he took such homogenization as a given, defining a nation as “a loose population spreading over a certain geographical portion of the earth’s surface, speaking a common language, and living in a homogeneous civilization.” Bourne was unable to see the ways that the homogeneity of such communities was in fact true only to the extent that they mimicked the same consolidating tendencies of the state and mainstream media. Transnational communities and their media were fraught with their own tensions and hierarchies, seen nowhere more clearly than in the question of language among the Greek-Orthodox immigrants of early-twentieth-century America.

If the Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians in Greece—where they were simply a “minority”—had been denied a voice in print media, then what chance did they stand in the United States, where they were the minority of a minority? They were, as this essay’s title suggests, the hyphens of hyphens.

Turkish-in-the-Greek-Script American Literature

Yet for all that, the Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Christians of America did not march silently into linguistic and ethnic oblivion. While much work remains to be done on this community, I have uncovered at least one writer, translator, and book-maker who produced his own Turkish-language poems, songs, and novels into the 1930s and 40s—a handful of which continued to circulate among his broader community decades after his death, still read by second-generation refugees (and interlopers like me!) today. I treat this case study in my larger monograph project, yet I’d like to sketch a quick outline here. In doing so, my aim is to generate a sense of the many similar stories still waiting to be recovered—the potential network of “Turkish-in-the-Greek-script American” texts that we might find once we start to scratch the surface.

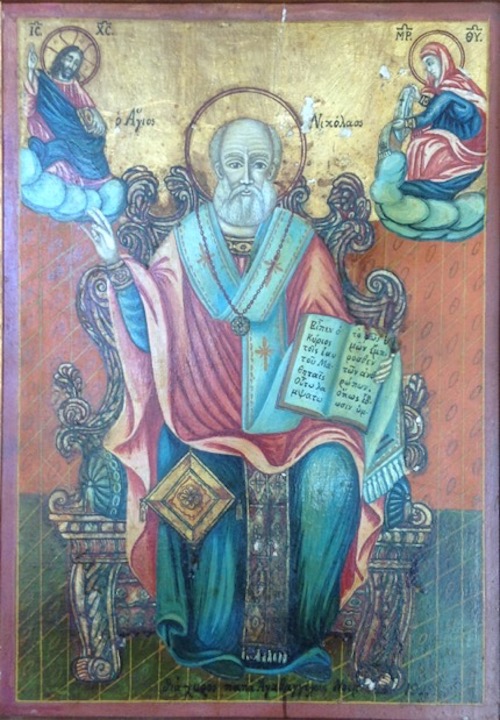

The man who made the books of my case study was named Agathangelos. While he’d spent the majority of his life in the Cappadocian village of Andaval (today’s Aktaş), at some point in the immediate aftermath of the Population Exchange he emigrated from Greece to Michigan, where his two sons had already settled. In Anatolia, he’d studied theology (during which time he’d also learned to read Greek) and had served as the village priest, a function that he continued in the city of Ann Arbor, performing the church rites and the weekly liturgy for the local Orthodox community from his son’s garage. In his spare time, Agathangelos drew pictures, painted icons, and wrote poems and long ballads.

One of these ballads, Ανδαβάλ Καριεσί ιτζούν διουζιουλεν δεσδαν (The Ballad of Andaval Village) was a heartbreaking narrative of his final days before the Population Exchange and his forced expulsion from Cappadocia, documenting the buildings and objects of his home and recounting their histories even as they were being seized and auctioned off by the Kemalist state. The poem, written in the traditional “destan” form of Anatolian oral poetry, was clearly meant to be recited aloud before an audience, as the first stanza immediately indicated:

Κέλιν ἐβλατλαρὶμ πενὶ τιγλεγί

σιζὲ

![]() βατανὴγ βασφὴν[η] ἐϊλεγίμ

βατανὴγ βασφὴν[η] ἐϊλεγίμ

![]() μδεν σόγρα χίτζ δουρμακσὴζ ἀγλεγίμ

μδεν σόγρα χίτζ δουρμακσὴζ ἀγλεγίμ

κέδιοροὺζ πουρδὰν γαϊρη νεϊλέγιμ

Gather round, my children, listen to me now;

let me sing this homeland’s story to you all,

let me weep black tears with every word I tell,

for we’re leaving this place, what else can be done?

The final stanzas of the poem, ten pages later, only reinforced the poet’s sense of tragedy—yet also his clarity of purpose in narrating it:

Κιορμεδὶμ δουνιαδὰ πὶρ καρὰρ ίομιούρ

ἐρίδιρ ἰνσανὴ ὀλσάδα δεμίρ

ραχὰτ ὀλμαδήκδζα καλπδεκὶ ζαμίρ

σιογλε

ἰομριού νεϊγελίμ

ἰομριού νεϊγελίμ

ὴμ δουνιάδα ἰομιοὺρ κορεγὶμ

ὴμ δουνιάδα ἰομιοὺρ κορεγὶμ

ἀλτηγὴμ ἀμανέτι κερὶ βερέγιμ

πίρδε ποῦ δεστάνα καλὲμ βουράγιμ

περκουζάρ ὀλσούν σίζε εϊβάχ νεϊλέγιμ

The world’s never seen the likes of this ordeal:

it breaks you down, even if you’re made of steel,

so long as you can’t bring your heart to heel,

tell me, with this ruined life what can be done?

I’ve lived in this world and may I see more yet,

may the charge that’s been entrusted me be kept,

may this, my ballad, to paper now be set

as a remembrance to you, what can be done?

As these brief excerpts make clear, the poem was bearing witness to a world that was vanishing, and it was doing so in an aesthetic form that made its function explicit: joining together a community through both (1) live oral performance (“listen to me now”) but also (2) a written form (“set to paper”). While their Turkish had been excluded from both English- and Greek-language print materials in the United States, poems and stories like these were “gathering together” their own community.

In the meantime, the Greek-speaking residents of Ann Arbor had begun to murmur at the indignity of taking communion from a Turcophone. [xxi] Unable or unwilling to read Agathangelos’s poems, incapable of imagining themselves among the community that he addressed repeatedly in his “σιζ” (you all), they moved to replace him. By the early 1930s, the church council had met with the Archbishop and agreed to procure a replacement—“to bring an appropriate priest” («θὰ φέρη εἰς τὴν Κοινότητα τὸν κατάλληλον Ἱερέα»), as the minutes of their special meeting read.

On a certain level, of course, this was only logical: those who spoke Greek must have felt the need for a priest who could fluently converse with them. Yet these changes came at the cost of marginalizing other, non-Greek voices. By 1935, with the construction of the new church (if not sooner), Agathangelos found himself again displaced. First, the Kemalists had forced him out of Cappadocia. Now, the Greek-speakers were forcing him out of his position in Ann Arbor. In his archive, I found a letter that he’d penned to the church committee shortly following his dismissal. Written in Agathangelos’s ungrammatical Greek, the letter is touching in its subtle anger and its restrained yet desperate grasping at some kind of parting dignity. He points out, without demanding anything, that they’d neglected to pay him the wages of his final month of work.

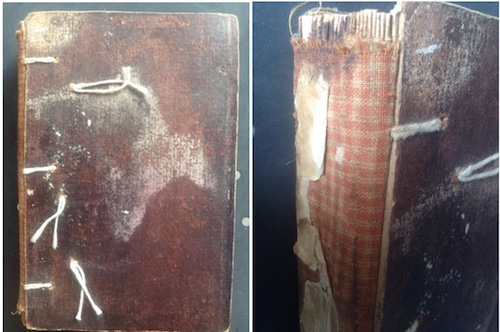

Cut off from his parish, Agathangelos nonetheless remained in contact with the larger though scattered community of Turkish-speaking Orthodox-Greek Americans across Michigan and beyond. It was also during this period, in the later half of the 1930s, that he began to write his own Turkish-language novels, which he adapted from Greek sources. He wrote these novels out by hand—over hundreds of pages—using whatever paper was available to him and binding them together into codices of his own making:

In some respects, these works appear to be what Bourne had denigrated as cultural “flotsam and jetsam”: the popular literature of adventure stories, romances, and ballads. Yet they were in reality so much more than this; they were a valuable communal tool for “gathering” up the Turcophone Greek-Orthodox Christians. Look, for example, to the location of the books today, ranging from the United States to Greece. While these books were initially the work of a single hand, laboring away in a quiet college town, their afterlives reached far beyond Agathangelos to the hands of others. For a community of “double hyphens” like the Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox Christians, those whose language and cultural memory had been brutally ostracized from print in Greece (and, to my knowledge, had never even gained a foothold in American print), Turkish-in-the-Greek-script books like these carved out a communal space within the larger cultural landscape of the United States, where the double forces of both Anglophone and Greek assimilation were pressing up against Turkish-speaking Greek Americans full bore.

Turkish-in-the-Greek-script American literature, I argue, was among the richest and most faithful representatives of Bourne’s “Trans-national America”: it productively wove together elements not simply from two “national” centers of gravity but from multiple linguistic and cultural nodes, ranging from adaptations of European novels to Anatolian ballads and folk songs—all of them inscribed in what was simultaneously the Turkish language and the Greek alphabet. It was a shining example of just how diverse the rich web-work of Greek America could be—so long as we preserve its threads.

A Call to Action for My Readers

Artemis Leontis has written that “there is too much of Greek America left over after one has rounded up the usual suspects”; to expand our field of vision, she offers us the notion of the net-work, drawn from lace-making: “The net-work presents a pattern of looped and knotted threads of connection, which form segments of closed and open spaces. No one segment is connected to all the rest and none stands alone, even if it has been created piecemeal” (1997:102). Turkish-language Greek American texts—and there are more of them, I’m sure—offer unexplored yet rich knotted threads of connection, segments of closed and open spaces. They stand as a fresh and exhilarating alternative to homogenization and consolidation. An alternative that we must take up today.

In today’s climate, the stories of Turkish-speaking Greek Americans demand an audience not simply for their own sake but for ours. At a time when attacks against so-called hyphenated Americans have again gained a terrifying momentum, the Greek American experience has an important role to play today. If it is to seize that role and play it to its fullest, however, it must do so, as Anagnostou writes, by foregrounding its “dazzling proliferation of identities”—including that of the Turcophone. Yes, parts of Greek America spoke, wrote, and sang [xxii] not only Greek but Turkish. And yes, we have indications that, at times, those who spoke primarily Turkish were the target of discrimination and exclusion, not only from the larger, mainstream WASP elite but from the elite within the Greek-Orthodox community itself. As the hyphens of hyphens, they offered up what was at once both the richest and most endangered example of a transnational Americanism. By taking up again and adding the “Turkish” threads to the tapestry of Greek America, we have the chance, one hundred years later, to begin to do justice to Bourne’s vision: a truly decentered loom, open to the hands and tongues of all.

How to make the most of this opportunity? With Agathangelos’s books, my hope is that I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of the Turkish-language literature of Greek America, but from this point onward the digging must be collective. While a few university libraries maintain small Karamanli collections, I remain hopeful that there is far more out there among the population at large. To recover and “weave together” these materials, our aim must be ambitious: the foundation of a comprehensive digital library of Turkish-in-the-Greek-script American texts.

To those of you reading this article, I extend an invitation: please pass this essay along to your family, friends, neighbors, and students within the Greek American community, with the hope that we will soon reach members or descendants of the Turkish-speaking Greek-Orthodox community. If indeed you identify yourself or your ancestors as part of the Turkish-speaking community, dig into your closets, shelves, and libraries; share this essay with your parents, grandparents, cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends and ask them to do the same. Gather up the loose-leaf sheets of writing, the notebooks, manuscript codices, and printed books of Turkish and let’s begin the process of networking them together in the form of a digital library. It makes no essential difference whether the first generation of your family spoke only Turkish or both Greek and Turkish. These kinds of distinctions might do more harm than help to the larger spirit of coalition building that drives us. And, just as important, I cannot emphasize enough the collaborative nature of this call to action. Make no mistake: if we’re to succeed in recovering and reintegrating these poems, stories, and memoirs into our lives, we must adopt the same communal network that has kept Agathangelos’s books alive.

It’s a model in which every handler becomes an equal curator.

And what precisely are we curating? Not simply a handful of old books and papers but a shared resource, like drinking water, whose destruction or survival depends upon the attention that we its caretakers devote to it—and to one another.

Maria Cotera, a scholar of Latina and Chicana feminists during the civil rights era, offers a way forward here. The digital collection that she cosupervises, Chicana Por Mi Raza, is not an “archive” but rather, in her terms, a “digital memory collective.” The difference is crucial. It is not Cotera’s collection; she merely helps coordinate it. It belongs to all its members, and anyone from the community can participate with full membership. It is collectively owned and maintained: contributors preserve the copyright to their contributions and can determine how they’re used; material archives are digitized in situ and rarely removed from their homes.

This is the future I foresee for Turkish-speaking Greek America: a collective digital library, assembled by and open to everyone who identifies as a member or ally of the community.

It is a future in the making. And it is up to you and me to make it.

Please reach out to me: stroebel@gmail.com

Will Stroebel teaches at the Modern Greek Program and the Comparative Literature Department at the University of Michigan. Before this, he was a Hannah Seeger Davis Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton University.

Cover Image credits: A manuscript replica of a page from Feth-i Konstantiniye (The Conquest of Constantinople), translated into Turkish (in the Greek script) by Evangelinos Misailidis, who was working from the Greek translation Poliorkia kai Alosis Konstantinopoleos (1859) of the German Belagerung und Eroberung Constantinopels durch die Türken im Jahre 1453: Nach den Original-Quellen bearbeitet (1858) by the Orientalist A.D. Mordtmann. The paper seen here has been taken directly from the advertising flyer (or letterhead?) of a Chicago-based lumber company. Image courtesy of Yorgos Kallinikidis.

Notes

I am very grateful to the time and labor that the blind readers, editor, copy-editor and webmaster gave this article.

[i] “The construction of usable pasts today,” Yiorgos Anagnostou writes, “guides how ethnicity is imagined tomorrow” (2009, 3).

[ii] Artemis Leontis (1997) also uses the physical process of weaving to define Greek America as a “net-work”: “Net-work suggests that we not look for a continuous, well-circumscribed plane in America densely occupied by Greeks and their offspring. Instead we should think of the different locations where Greek interests coincide or collide. We should consider nodes of activity—some interconnected, some isolated, some few and far between” (93).

[iii] Even today, the genocide of indigenous Americans remains just beyond the threshold of mainstream cognizance. In 1991, for example, several U.S. senators “threatened to cut funds to the Smithsonian Institution if a film that it was partially funding used [the] word [genocide], even in passing, to describe the destruction of the Western Hemisphere’s indigenous peoples” (Stannard 2000 [1995], 247).

[iv] Writing a generation after Bourne, Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy (1991 [1957]) studied the evolution of mass publishing in Britain, contextualizing it through the reading practices and creative culture of the working class. The control of media production, he wrote, was drifting further away from the communities themselves into the hands of an increasingly consolidated commercial class, such that “the appeals made by mass publicists are for a number of reasons made more insistently, effectively, and in a more comprehensive and centralised form than they were earlier; that we are moving towards the creation of a mass culture; that the remnants of what was at least in parts an urban culture ‘of the people’ are being destroyed; and that the new mass culture is in some important ways less healthy than the often crude culture it is replacing” (9-10).

[v] See McCarter’s recent Young Radicals (2017), from which I’ve drawn Sedgwick’s letter as well (123).

[vi] Within five months of the Espionage Act of 1917, the Postmaster General had banned every major socialist publication from circulation at least once (McCarter, 179); over a hundred Wobbly union organizers were arrested and put on a mass show trial for encouraging draft evasion (despite the IWW’s official silence on the war); and the following year a young J. Edgar Hoover launched what have become known as the Palmer Raids, blacklisting and arresting 10,000 foreign-born leftists in the first Red Scare. Five hundred of these “hyphenated” Americans were eventually deported.

[vii] See Yiorgos Anagnostou (2004), p. 62, note 18.

[viii] The editorial in question comes from The New Republic. As McCarter writes, “Instead of regarding this anti-majoritarian act as a failure of democracy, the editors s[aw] it as a cause for champagne” (168).

[x] “The dominant media firms,” Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky write, “are quite large businesses; they are controlled by very wealthy people or by managers who are subject to sharp constraints by owners and other market-profit-oriented forces; and they are closely interlocked, and have important common interests, with other major corporations, banks, and government” (1988, 14).

[xi] See, for example, New York Times, “Pacifist Orator Vanquished” (Aug. 15, 1917).

[xii] Anagnostou further notes, for example, that “a significant number of Greek Americans were particularly vocal, in their ethnic media, in expressing their discontent about the vociferous opposition of homeland Greeks to the 2003 US war in Iraq. In the political culture at the initial stages of the war, when criticism of US military action was stigmatized as unpatriotic, Greek Americans went to great lengths to differentiate themselves from the ideology of the Greek public” (2003, 285).

[xiii] Looking back over the early history of the United States, Bourne saw a precedent for this strangling: “Modern historians reveal the avowedly undemocratic personnel and opinions of the [Constitutional] Convention. They show that the members not only had an unconscious economic interest but a frank political interest in founding a State which should protect the propertied classes against the hostility of the people. They show how, from one point of view, the new government became almost a mechanism for overcoming the repudiation of debts, for putting back into their place a farmer and small trader class whom the unsettled times of reconstruction had threatened to liberate, for reestablishing on the securest basis of the sanctity of property and the State, their class-supremacy menaced by a democracy that had drunk too deeply at the fount of Revolution.... Every little school boy is trained to recite the weaknesses and inefficiencies of the Articles of Confederation. It is taken as axiomatic that under them the new nation was falling into anarchy and was only saved by the wisdom and energy of the Convention.... Under the Articles the new States were obviously trying to reconstruct themselves in an alarming tenderness for the common man impoverished by the war. No one suggests that the anxiety of the leaders of the heretofore unquestioned ruling classes desired the revision of the Articles and labored so weightily over a new instrument not because the nation was failing under the Articles, but because it was succeeding only too well. Without intervention from the leaders, reconstruction threatened in time to turn the new nation into an agrarian and proletarian democracy. It is impossible to predict what would have materialized.”

[xiv] In 1915 a secret treaty among Britain, France, and Italy had foreseen the partition of the Ottoman Empire into “spheres of influence”— stepping stones to their colonial interests. Izmir had been apportioned to Italy but, with the later entrance of Greece into the war (on the promise of territorial compensations in Asia Minor), Britain eventually decided to grant Izmir to Greece. This decision produced no small friction with Italy, demonstrating both the fragile alliances between the occupying powers and the Realpolitik driving them.

[xv] Between 1900 and 1924, 20 percent of the total number of Greek immigrants to the United States (roughly 100,000 of the 500,000) had come not as Greek but as Ottoman subjects. Paschalis Kitromilides and Alexis Alexandris (1984–1985, 34) estimate that around 60,000 refugees from Asia Minor went on to emigrate beyond Greece.

[xvi] See Evangelia Balta and Aytek Soner Alpan (2016, 163).

[xvii] In her unpublished dissertation (2014), Bilal Sert notes that at the start of the century, many Greek-Orthodox immigrants from Rumelia and Anatolia sampled in her case study provided Greek passports to Sunni Turkish friends, migrating together and helping them find housing and employment in the United States. In at least one instance, a Greek laborer and union organizer was also recorded in 1912 addressing (in Turkish) a group of Sunni Turkish workers, informing them of their rights. From Sert’s oral histories, we also learn that, in New York, Greek Americans participated in yearly Turkish Independence Balls!

[xviii] Ἐθνικὸς Κῆρυξ (Aug. 23, 1923). I’m grateful to Papadopoulos (2013, 238) for leading me to this article.

[xix] For all of these examples, see chapter 6 of Anagnostou 2009.

[xx] It is also worth mentioning the path-breaking work of an earlier generation, such as Helen Papanikolas.

[xxi] From an interview with Agathangelos’s great-granddaughter, who, drawing from the research of a relative, noted that “half the parishioners in Ann Arbor liked him and half did not, basically because he didn't speak Greek. How sad” (Aug. 1, 2017).

[xxii] The song in the link belongs to Achilleas Poulos, “Neden Geldim Amerika’ya” (Why did I come to America?), a bitter song of gurbet (i.e., estrangement in foreign lands, akin to ξενιτιά). Sung in Turkish, it is addressed to a broader Ottoman-American audience spanning Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Sunni Turks and Sephardim, among others. Interestingly, this song was so popular among Turkish-speakers that decades later it was adapted in Turkey as “Nedem geldim İstanbul’a” (Why did I come to Istanbul?), capturing the period of industrialization and internal migration that drew large portions of Turkey’s agrarian population into its urban center. For further examples of Greek American Turkish song, see Panayotis League’s dissertation, “Echoes of the Great Catastrophe: Re-Sounding Anatolian Greekness in Diaspora” (2017), or Ian Nagoski’s popular compilation, To What Strange Place?

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “Model Americans, Quintessential Greeks: Ethnic Success and Assimilation in Diaspora.” Diaspora 12 no. 3 (Winter 2003): 279–327.

——— . “Forget the Past, Remember the Ancestors! Modernity, Whiteness, American Hellenism, and the Politics of Memory in Early Greek America.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 22, no. 1 (2004): 25-71.

——— . Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America . Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009.

Anonymous. “Pacifist Orator Vanquished.” New York Times, Aug. 15, 1917, p. 4.

Balta, Evangelia. Beyond the Language Frontier: Studies on the Karamanlis and the Karamanlidika Publishing . Istanbul: İsis, 2010.

Balta, Evangelia, and Aytek Soner Alpan, eds.. Μουχατζηρναμέ —Muhacirnâme: Poetry’s Voice for the Karamanlidhes Refugees . İstanbul: Istos, 2016.

Barron, Clarence W. “The Road to Peace.” The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 23, 1917 (morning edition).

Bourne, Randolph. “Trans-national America.” Atlantic Monthly, v. 118 (Jan–June 1916): 86–97, <babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.73001806;view=1up;seq=98>.

———. “War and the Intellectuals.” Seven Arts vol. 2 (June 1917): 133–146, <fair-use.org/seven-arts/1917/06/the-war-and-the-intellectuals>.

——— . “The State.” Untimely Papers. Edited by James Oppenheim. New York: B.W. Heubsch, 1919, 140-230, <fair-use.org/randolph-bourne/the-state/>.

Canoutas, Serapheim. «Ἡ ἑλληνική πολιτικομανία» [Greek Obsession with Politics]. Ἐθνικὸς Κῆρυξ, Aug. 23, 1923, p. 4.

Clayton, Bruce. Forgotten Prophet: The Life of Randolph Bourne. Baton Rouge: University of Missouri Press, 1984.

Cotera, Maria, et al. Chicana por Mi Raza. <chicanapormiraza.org/>.

Derrida, Jacques. “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression.” Translated by Eric Prenowitz. Diacritics 25/2 (1995): 9-63, <newsgrist.typepad.com/files/derrida-archive_fever_a_freudian_impression.pdf>.

Georgakas, Dan. “Greek American Radicalism: The Twentieth Century.” The Immigrant Left in the United States, edited by Paul Buhle and Dan Georgakas, 207–32. Albany: SUNY Press, 1996.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited and translated by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. London: International Publishers, 2007 [first Italian edition 1947–1951].

Herman, Edward, and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing Consent. New York: Pantheon Books, 1988.

Hoggart, Richard. The Uses of Literacy. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1991 [first edition 1957].

Kitromilides, Paschalis, and Alexis Alexandris. “Ethnic survival, nationalism and forced migration: the historical demography of the Greek community of Asia Minor at the close of the Ottoman era.” Bulletin of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies 5 (1984–1985): 9–44.

League, Panayotis. “Echoes of the Great Catastrophe: Re-Sounding Anatolian Greekness in Diaspora.” PhD diss., Harvard University, 2017.

Leontis, Artemis. “The Intellectual in Greek America.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 23, no. 2 (1997): 85–109.

McCarter, Jeremy. Young Radicals: In the War for American Ideals. New York: Random House, 2017.

Nagoski, Ian. To What Strange Place: The Music of the Ottoman-American Diaspora, 1916-1929 . 2012. <ww.tompkinssquare.com/archives/159>.

Okker, Patricia (ed.). Transnationalism and American Serial Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2012.

“Our Saint Nicholas Parish.” <www.stnickaa.org/about-us/history/our-saint-nicholas-parish>.

Pappadopoulos, Yannis. «Η μετανάστευση από την Οθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία στην Αμερική (19ος αιώνας-1923): Οι ελληνικές κοινότητες της Αμερικής και η αλυτρωτική πολιτική της Ελλάδας» [Migration from the Ottoman Empire to America (19th century-1923): The Greek communities of America and Greece’s irreidentist policy]. PhD diss., Panteion University, 2008.

———. «Κράτος, Σύλλογοι, Εκκλησία: Απόπειρες ελέγχου των Ελλήνων μεταναστών στις ΗΠΑ στις αρχές του 20ου αιώνα» [State, Associations, Church: Attempts to control Greek immigrants in the US in the early 20th century]. Το έθνος πέραν των συνόρων: «Ομογενειακές» πολιτικές του ελληνικού κράτους [The nation beyond borders: “Diaspora” policies of the Greek state], edited by Lina Ventura and Lambros Baltsiotis, 219–52. Athens: Vivliorama, 2013.

Poulos, Achilleas. “Neden Geldim Amerika’ya” [Why did I come to America?]. <www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLoekQOQ5RM>.

Sert, Bilal. “The Missing Link: Early Turkish Immigration to the United States in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries.” PhD diss., Texas Women’s University, 2014.

Shupak, Gregory. “US Isn’t Leaving Syria—but Media Lost It When Possibility Was Raised.” Fair. April 6. 2018. <https://fair.org/home/us-isnt-leaving-syria-but-media-lost-it-when-possibility-was-raised/>.

Stannard, David. “Uniqueness as Denial: The Politics of Genocide Scholarship.” In Is the Holocaust Unique? Perspectives on Comparative Genocide , edited by Alan Rosenbaum, 245–90. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2000 [first edition 1995].

Vouvakis, Yannis, and M. Visanthis (directors). Η Σύγχρονη Σκέψη: Πανελλήνια Επιθεώρηση [Modern Thought: Panhellenic Review]. Chicago, 1928.

Wilson, Woodrow. “Final Address in Support of the League of Nations.” American Rhetoric, <www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/wilsonleagueofnations.htm>.

Young, Art. “Having Their Fling.” Masses 9, no. 11 (Sept. 1917): 7.