The Politics of Life and Death: Working-Class Greek Immigrant Women and the Castle Gate Mine Disaster—A Tribute

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

The women of Carbon County mining towns deserve more than this brief sketch. […] Their descendants are scattered worldwide; they hold high positions in the armed forces, in the professions, in business, and in government. Some remain in Carbon County, close to their heritage. One hopes that memories of family matriarchs are still unfaded, that they are more than old photographs in picture albums.1

Abstract

The Castle Gate Μine no. 2 disaster (March 8, 1924) killed 171 coalminers, 114 of whom were married, leaving “417 dependents, including 341 children and 25 expectant mothers. … The families of 143 men were left without income or assets.”2 Fifty (in some accounts, 49) were Greek, leaving 19 widows and 41 orphans. How did this latter demographic cope with the destruction of their families? What were their available options, the social conditions, and the criteria for the strategies and tactics the bereaved women pursued to manage the crisis?

This writing, the second installment of my tribute to the Castle Gate centenary, draws from the available literature to explore how the mining industry and the state were implicated in the disaster—and the deaths it caused, and how industry and government were involved with the lives of the widows and orphans. Reading the published archive from a cultural studies perspective, the analysis focuses on the power relations entangling these entities in connection to what I call the “politics of life and death.” The concluding remarks reflect upon the implications of this knowledge about reigning power and ruined lives toward a critical historiography of Greek America.

Classified Photograph Collection, Courtesy of the Utah State Historical

Society.

Used by permission.

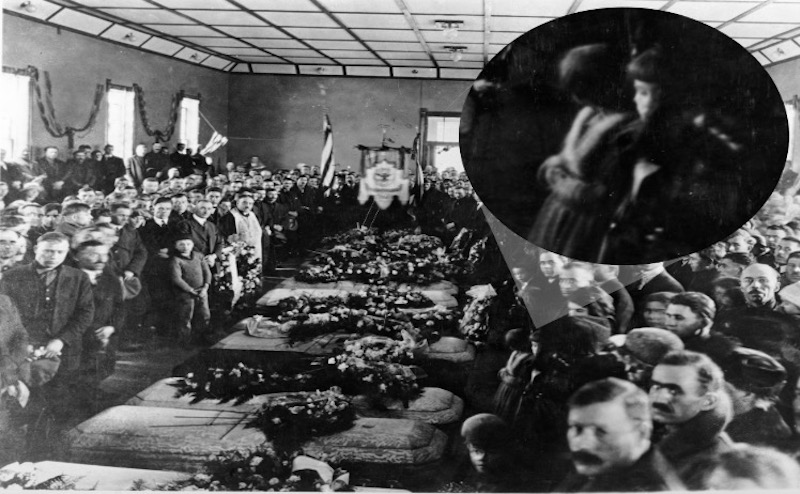

A photograph taken in the immediate aftermath of the Castle Gate Mine Disaster offers a macabre visual fragment of the dramas confronting the families of those killed. Preserved at the Classified Photograph Collection of the Utah State Historical Society, the image captures the mass burial services for some of the Greek immigrants killed in the explosion. The setting is one of the public halls in the town converted to makeshift morgues before the bodies were carried to Price, the seat of Carbon County, located about three miles south of Castle Gate. They were buried in a plot purchased by the local Assumption Hellenic Orthodox Church for this purpose at the town’s cemetery.

The photograph captures a historical moment of a coalmining immigrant

community in sorrow. The living gathers in mourning, their bodies circling

densely around the deceased in sealed coffins, entombing their horrific

disfiguration. The faces of the participants, mostly male, appear stunned.

With a few notable exceptions, the majority turns to face the camera,

responding to the photographer. The overwhelming presence of death in the

temporary morgue must have heightened the intensity of the proximity the

miners must have felt to the grave dangers of an occupation infamous for

sudden and untimely deaths. A historical moment of the working class in

mourning is caught visually in its immediacy, now a powerful archival

document available for reflection.

Looking closely, you can see two children at the right front as we face the image, which caught my attention. The enhanced closeup, shown above, brings their body language into focus. The children’s position in the front row close to a casket indicates they must have been two of the 41 orphans, yet an additional ordeal of the calamity. The woman standing behind them, most certainly their mother, her gaze downcast, is absorbed in grief. This centering enables the viewer to discern one of the children embracing a sibling of whom we see the back of the head. A family in distress entangles together for the final farewell to a husband and father, a brutal introduction to the precarious life of coal mining families.

The burials materialized the wives’ worst fears. Being aware of the ubiquity of deadly or incapacitating industrial incidents, their everydayness was haunted by the specter of an “accident.” Regional statistics illustrate the material basis of this apprehension. “From 1914 to 1929, Utah’s number of fatalities in relation to hours worked and tons mined was almost twice the national average.” The horror of husbands “being killed from a fall of coal or in explosions” motivated many women in the County to take boarders, wash the clothes of bachelor immigrants, and cook for them as a “means of accumulating money to help their husbands enter business or become sheepmen.”3

The dramatic, eerie outpouring of grief in their lamentations was amplified by the fact that some were newly married, even pregnant at the time. The strain was compounded by the additional loss of a brother or other relatives, including those of the deceased husbands. Chain migration—family and regional—resulted in a high concentration of related individuals in coalmining towns and, consequently, multiple losses in the event of a disaster, augmenting the scale of the death toll on a family.

The question “What’s next?” was likely lurking in the minds of the widowed amidst this shocking devastation. In the working-class experience of death, the emotional toll of the loss, material worries, and shared concerns about the future may coexist within a complex structure of feeling. When the gendered division of labor assigns the role of the sole breadwinner to males, it exacerbates the financial worries of the bereaved women.4 The coal mining experiences of death among Greek widows in the region made them cognizant, as I noted, of the ever-present danger and encircling hardships.

Helen Papanikolas, an authoritative historian of the Greeks in Carbon County, brings home the anxieties of poverty, social isolation, and dependence confronting a widow:

The death of a father was a horrendous tragedy that left his wife and children without any means of support. In industrial accidents, death benefits from management and from Greek lodges were small and quickly dissipated. A mother was helpless to provide for her children. She dyed the window curtains, her clothing, and the children’s clothing black, turned mirrors and photographs—objects of vanity and pleasure—toward the wall. She could not leave her house to work for others and flout custom; she could wash and iron for other women in her home for a pittance. If her husband had a male relative, he would occasionally give her a ten-dollar bill and bring a bag of flour. Often, churches provided some help. Greeks, at times, took up a collection to send a widow and her children back to her native topos.5

Source: “Greeks in Utah,” Utah Historical Society, People of Utah

Photograph Collection, 1919, 2008. Used by permission.

At the time of the Castle Gate mine disaster, some of the Greek widows must have been married for more than a decade. Beginning in the 1910s, women started arriving in the region as brides, their weddings offering passage to the culturally desired marital status, hopes for escaping poverty, and, in turn, occasions for pleasurable sociability. The challenges were daunting: women “lived with unrelenting toil and with fears of being forced out of company houses during labor wars, [and] of dying in childbirth … Over all hovered the anxious perplexity of being unwanted aliens.”6

Women’s degree of acculturation was significantly less than their husbands’ as some were relatively new arrivals, and the lives and labor of most, if not all, must have revolved around the home and immigrant social circles. Being dependent on their husbands for a living and having inadequate English, they faced limitations in negotiating with the outside world. The prospect of remarrying for many was dubious, subject to traditional expectations, including regionalism. A widow who “lost both her husband and a brother in the mine explosion” faced the following issues:

For the next six years, she continued to live in Utah with her unmarried brother and a daughter born to her a few months after the disaster. In 1930, the social worker suggested “that she should seek employment among her countrymen. . . . She said there is no work that a Greek woman can do in Salt Lake. . . . [The social worker] suggested a remarriage. She said she had opportunities to remarry, but not of the men of her own section of Greece [Crete].”7

An eye-witness account portrays a domestic reality of mourning, saturating a family’s everydayness. Steve Sargetakis, an orphan of the disaster, remembers his mother spending the rest of her life in mourning—wrapped up in the power of traditional gender dictates: “My mother wore black for the rest of her life,” he recalls. “We had black curtains at our windows, and we had no parties or celebrations.”8

The options for mobility were primarily limited: return to their villages or turn toward family networks in the new land for support, safety, and solace. Few commenced a new beginning connected with changes in their identities and roles. One widow, a mother of three, moved to California in 1926, where she joined her cousin and explored work opportunities where, she “could get work at much better wages.” She remarried.9 For others, though, widowhood coupled with destitute meant a new phase of acute precarity.

Adaptation strategies varied depending on circumstances, the key variables involving the availability of kin in the United States, the age of sons, or the marital prospects of a daughter. One widow, “so distraught with the loss of her husband that insanity was feared, took her three young children and left for New Jersey where a cousin lived.” Another, “pregnant and with a child fifteen months of age, went to Connecticut to be with her immigrant brother and sister.” Yet another, “who at first wanted to return to Greece with her five children … was persuaded by her oldest son, who feared induction into the Greek army, to remain in America. He was old enough to support the family through his work and to perform the social linking tasks Greek custom dictated should fall to the males of the family.”10

To counter these challenges was the all-important issue of legally mandated financial compensation. The situation for the widows in 1924 was improved compared to seven years prior when the lack of a worker’s compensation law in Utah freed employees “from responsibility in industrial accidents.”11 The passing of the 1917 law in the state offered a measure of relief, requiring the Castle Gate owing company to pay benefits, which in 1924 amounted to 60% of the weekly wages of the husbands over six years. Still, the funds were deemed insufficient by the Committee set by the Governor to investigate the situation of the dependents, calling for additional relief, as I will explain.

Company relief might have been “barely adequate for life in America,” but “would seem a lavish amount” upon return to Greece.12 Six women and their families received additional funds from the Castle Gate Relief Fund Committee for the cost of transportation, including a mother with five children. Others returned, but only after trying alternative routes first.

Many opted to remain in the United States, citing material and cultural considerations as well as their children’s prospects in the country. One deterrent for returning was facing dependency on family or in-laws.

Three Cretan widows returned to Crete with their children. The rest of the women remained, knowing that life in the homeland for widows and orphans would be almost intolerable. At least in America, they said, their children would get an education.13

Mining Disasters and the Politics of Death

It is impossible to disentangle the understanding of the Castle Gate bereaved families from the cause of the mine explosion—the source of their torment.

A close look at the economic calculus connected with the disaster illustrates the interests of industrial capitalism in putting profits first over the miners’ lives. Overall, the mining industry was aware of the inadequacy of its safety measures yet largely unresponsive at the time to implement the proven effective alternative technologies recommended by the U.S. Bureau of Mines. Enabled by lax state laws, this neglect allowed for a “politics of death” in which the economic calculus of profit deemed the large-scale loss of laboring bodies an acceptable risk.14

The death of the miners and the anguish of their families is best understood then as the result of social violence, the way disasters were seen generally as “clear markers of the violence of capitalism.”15 The immediate aftermath of disasters provided a platform for the bereaved communities, unions, and the socialist press for the political expression of working-class grief and grievances.

How did the Greek widows feel about the role of the coal industry at Castle Gate? Did they express anger? Did their laments—an acceptable cultural outlet for women in rural Greece to blame the agents of death—voice critique of institutions or express subversive calls for revenge?16 Published accounts incorporating the women’s perspectives offer only a fleeting glimpse of their wants, requests, and perhaps resistance tactics.

Governmental Benevolence and the Politics of Life

The Castle Gate Disaster triggered a major financial, economic, and emotional crisis in the coal mining community in Utah and nationally. Seen in the context of a series of deadly disasters fresh in the community’s memory, this new devastation required management, indeed mobilizing a regional government-led initiative seeking to control the crisis through humanitarian discourse, demonstrating in this manner its benevolence. If the state had its share of the blame to bear for the death politics of the corporations,17 it now sought to restore its image via a politics of life to sustain those subjected to the violence of capitalism.

Given the inadequacy of the legal compensation to the victims’ families, as I have indicated, the Governor launched a public donation campaign, signing “a proclamation appealing to the people of Utah and surrounding states to come to the aid of the distressed widows and children.”18 A network of civic and economic organizations, including the Red Cross, churches, banks, the Boys Scouts, professional men and women as well as city and county officials, responded, contributing a total of $132,445.13. The Castle Gate Relief Fund Committee, a social welfare organization, was formed to oversee the disbursement of the funds.

The Committee’s criteria in the allocation of the monies extended beyond strict economic considerations. It paid close attention to the human aspects of the ordeal, classifying the applicants into three “classes,” prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable members—mentally distraught widows, families in dire poverty, and children confronting life-threatening conditions. These “more helpless families” “had four or more minor children and no insurance or other income except that provided by workmen’s compensation.” They were in poor health and emotionally shattered.19 It was estimated that each would need as much as $500.00 per month for a long time, perhaps fifteen years.

Led by a salaried social welfare director, the Committee’s practices extended beyond strict economic aid. It regulated the social conduct of a population under duress based on close surveillance. The work ethic of the applicants was monitored, and if they were found “lazy” in performing domestic tasks, they were deemed unworthy of aid. Special care was attributed to under-nourished children. Women were instructed to remarry or encouraged to join the Mormon Church as a means of receiving aid; girls were guided to attend school—instead of marrying early. The work of the Committee practiced a life politics of disciplining this demographic, investing in the restoration of its emotional health, productivity, and reproductive potential—its operation that is as functioning normative citizenry.20

In this context, the published archival fragments associated with the work of the Committee offer documents—oral testimonies, reports, relief applications—in which we hear the voices, or perhaps more precisely “whispers” given their small scale, of the Greek widows expressing wants, wishes, and dreams for the future. Across the interstices of their statements, one could trace registers of discontent, micro-practices of resistance against the control of their lives, implicit resentment, and perhaps even acts of symbolic revenge.

A Greek widow, for example, voiced the request for a “big house from company, so she can take boarders,” underlying her desire for greater compensation for the scale of her loss. Another, who lost her husband and three of his relatives in the disaster, seemed to long for a domestic tranquil spaciousness for her children; she wanted “a little place where she can have chickens and where there is room for the children to play. … She could not get enough money ahead to get a coat for herself; she seems to put all of it on the children.”21

In another instance, a widow who applied for transportation funds had no intention of returning to Greece. When the monitoring Committee discovered that she would instead use the money “to invest in some business and remain in Helper [a nearby town],” its members expressed annoyance. Yet her act of “deception” might have constituted a form of retribution for the wrong she was (unjustly) inflicted. And when another requested “a thousand dollars and would go [return] when she got ready,” she was not only expressing the expectation for greater compensation but also a measure of agency outside the regulatory dictates of the Committee.22

We could plausibly understand these archival traces of women’s requests as resistance, as “weapons of the weak.”23 The women may have exercised the limited power they possessed to manipulate a politics of life whose very public gesture of dispensing care hid the structures of death politics, resulting in the wreckage of their lives.

The intersectional status of the widows as poor, women, and immigrants added to their powerlessness. The traditional gendered division of labor compromised their linguistic acculturation, which, coupled with their poverty, was neglected in a key procedure for considering the granting of relief. The required application, including the questionnaire, made the hiring of interpreters necessary “to translate, write, and speak” for the women. Lack of resources or perhaps unwillingness to engage in this bureaucratic process, which must have felt onerous, might have been the reason that many widows “decided to return to former homes elsewhere in the United States or to their native countries.”24 The women’s limited skills in English being common knowledge, the process discriminated against destitute immigrant women lacking resources to negotiate it.

The loss of life of a husband at work in coalmining immigrant families was inextricably linked to a host of anxieties—emotional torment, economic hardships, social isolation, sexual loneliness, and fears of exploitation. The status of the widows and the orphans as a powerless immigrant demographic presented an additional threat of violence being inflicted on their bodies. The molestation of an orphan girl, coupled with the near acquittal of the perpetrator,25 revealed a lurking problem indicating their vulnerability as targets to predatory abuses. How did the abused girl and her family cope with the trauma? How did this experience shape their lives as immigrant persons at risk of exploitation? How did they further feel when, “soon after” the disaster, the Ku Klux Klan escalated “the threat of violence toward Catholics and immigrants”? By summer, Papanikolas reports, “it was burning crosses” in the locality.26

One of the most dramatic cases connected with the long-term impact of the disaster involved a returnee to her village in Crete who “bowed to despair and insanity and died in 1927,” one more side victim of the disaster.27 As a returnee, she did not qualify for relief from the Committee beyond her transportation cost. The Committee’s life politics—repatriation—to address her predicament proved inadequate to avert her tragic end.

These oversights illuminate a broader ideology in the Committee’s biopolitics—its privileging the national context in the restoration of productive and reproductive bodies. One of its early stipulations was to exclude from aid those widows who lived overseas. Though the state and mining industry’s economic gains depended on the toil of transnational migrant labor, they failed to press for compensating the impoverished families of the victims living outside the nation.

“When do the losses from injury end?” “Do they ever?” Work-related injuries “haunt the living.”28 They severely compromise the quality of their lives, even extracting the ultimate price, death due to the weight of grief. How does one measure the extent of these losses and, ultimately, the value of the lives of those intimately involved? The life politics of the Castle Gate Relief Fund may have provided temporary aid to avoid social collapse. Still, ultimately, it depoliticized the issue, failing to address the ethical and political issues raised by institutionalized violence wrecking human lives.

In Lieu of Conclusion

I ponder the closing angle for this writing about a topic that resists closure. Much archival work waits to be done on death, grief, and loss among working-class industrial workers. The specter of preventable human suffering, the needless social violence29 to which they were subjected, is haunting, demanding that we do something as this painful past entangles with the present.

Little is known about the lives of the Castle Gate widows and orphans, but also the families of thousands of immigrants killed in industrial accidents. Calling for research on this subject presents an obvious need for historical remembering, of recognizing the significance of these figures as “more than old photographs in picture albums.”

This subject raises a host of questions: How did the “survivors” cope with the trauma? How did they express their grief as a working class? Whom did they blame? And, for my purposes, how does their experience inform the practice of Greek American history? Given the meager archive, a project aiming at this recovery will be confronted with gaps and silences, diminishing primary resources and dimming social memory.

The framework of inquiry is evidently broader than immediate death in the industrial workplace. It also involves injuries and hastily performed amputations, often ruining the occupational, social, and personal lives of the victims. Third-generation families still hold memories of irresponsibly conducted dental surgeries resulting in death.30 Many widows never received worker’s compensation. Black lung decimated coalminers long after they left their occupation. Many workers, including labor organizers, were killed unjustly by authorities. Trauma, and even insanity, devastated families. Major institutions failed immigrants, leaving piles of lives destroyed, the intangible ruins of that era.

To orient our critical task in view of the wreckage, I turn to the insights of Walter Benjamin. Benjamin writes about the ethical and political responsibility of historians to keep producing work “brushing history against the grain,” illuminating, that is, marginalized demographics marked by limited archival traces.31 His work directs attention to the ruins of the past—in our case, lives torn down under industrial capitalism and state complicity. It advocates historical writings against official or prevailing narratives that fail to acknowledge those ruins. This countering of dominant truths inevitably animates a politics of remembering.

In fact, it extends the prospect for Greek American historiography driven by this dual, interlaced commitment: historical remembering of those killed, persecuted, devalued, maligned, or marginalized who left scant archival traces and illuminating those individuals, institutions, intellectuals, grassroots initiatives, authors, who have been working and writing against the grain—resisting normative social structures and their supporting cultural representations.

This historiographical mode would contribute toward the project of countering the growing danger of ahistorical heritage narratives, which increasingly blanket the public sphere. Devoid of ethnographic and historical texturing, “ethnic heritage,” as it is practiced in the context of liberal multiculturalism, produces narratives of cultural and economic triumphs, pride, and cultural distinction via sanitized, self-congratulatory narratives. When early immigrant poverty and hardships are often recognized, they are cast as evidence of resilience leading to immigrant mobilities. Read against the tragedies of the industrial working class, these narratives are an insult to lives disrupted by institutional social violence and the responsibility of remembering historically.

Contextualizing this work’s trails of evidence in this manner highlights a moment when the danger of prevailing narratives writing off the abuses of industrial capitalism and its agents is despairingly real. Their act of covering up human ruins animates a politics of diasporic writing against the grain, committed to the responsibility of recovering their presence and its implications for an ethical telling of history today.

May 18, 2024

Yiorgos Anagnostou is a Modern Greek studies Faculty at the Ohio State University.

Notes

1. Helen Papanikolas, “Women in the Mining Communities of Carbon County.” In Carbon County: Eastern Utah’s Industrialized Island, edited by Philip F. Notarianni, 81–102 (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1981), 101.

2. Michael Katsanevas Jr., “The Emerging Social Worker and the Distribution of the Castle Gate Relief Fund.” Utah Historical Quarterly 50.3 (1982), 245. The Castle Gate Relief Fund Committee later revised the original statistics.

3. Helen Papanikolas, “Women in the Mining Communities of Carbon County,” 86, 82, 89.

4. Julie-Marie Strange, “‘She Cried a Very Little’: Death, Grief and Mourning in Working-Class Culture, c. 1880-1914.” Social History 27.2 (May 2002).

5. Helen Papanikolas, An Amulet of Greek Earth: Generations of Immigrant Folk Culture. (Athens, OH: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press, 2002), 169–70.

6. Helen Papanikolas, “Women in the Mining Communities of Carbon County,” 82.

7. Janeen Arnold Costa, “A Struggle for Survival and Identity: Families in the Aftermath of the Castle Gate Mine Disaster.” Utah Historical Quarterly 56 (1988), 285.

8. Arva Smith, “Castle Gate Mine Explosion,” reprinted from Sun Advocate (1985). For the obituary of Steve Sargetakis (1922-2005), see here.

9. Janeen Arnold Costa, “A Struggle for Survival and Identity,” 285.

10. Ibid., 284.

11. Michael Katsanevas Jr., “The Emerging Social Worker and the Distribution of the Castle Gate Relief Fund,” 242.

12. Janeen Arnold Costa, “A Struggle for Survival and Identity,” 283.

13. Helen Papanikolas, An Amulet of Greek Earth,169.

14. Yiorgos Anagnostou, “On the Causes of the Castle Gate Mine Disaster (1924): Science, Industrial Capitalism, and the Law.” Immigrations–Ethnicities–Racial Situations. May 9, 2024.

15. Samira Saramo, “Capitalism as Death: Loss of Life and the Finnish Migrant Left in the Early Twentieth Century.” Journal of Social History 55.3 (2022), 670.

16. See Gail Holst-Warhaft, Dangerous Voices: Women’s Laments and Greek Literature. (New York: Routledge, 1992). Research on how the Greek immigrant press and organizations covered the disaster could provide insights into this question.

17. Yiorgos Anagnostou, “On the Causes of the Castle Gate Mine Disaster (1924).”

18. Michael Katsanevas Jr., “The Emerging Social Worker and the Distribution of the Castle Gate Relief Fund,” 245.

19. Ibid., 248.

20. I draw here from Michel Foucault’s notion of biopolitics.

21. Michael Katsanevas Jr., “The Emerging Social Worker and the Distribution of the Castle Gate Relief Fund,” 252.

22. Ibid., 249

23. James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. (New Haven: CT, Yale University Press, 1985)

24. Michael Katsanevas Jr., “The Emerging Social Worker and the Distribution of the Castle Gate Relief Fund,” 248.

25. Ibid.

26. Helen Papanikolas, “Women in the Mining Communities of Carbon County,” 96.

27. Janeen Arnold Costa, “A Struggle for Survival and Identity,” 291.

28. Nate Holdren, Injury Impoverished: Workplace Accidents, Capitalism, and Law in the Progressive Era. (Cambridge University Press 2020), 254.

29. See, Mark Aldrich, “Preventing ‘The Needless Peril of the Coal Mine’: The Bureau of Mines and the Campaign against Coal Mine Explosions, 1910-1940.” Technology and Culture 36.3 (1995), 483–518.

30. Leonidas Vardaros (writer and director), Ludlow: Greek Americans in the Colorado Coal War. Produced by Apostolis Berdebes, Non-Profit Company, 2016.

31. Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” In Illuminations , edited by Hannah Arendt, 253–64. Trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 257.