Cavafy in Detroit: Dan Georgakas Cuts and Pastes

By Gregory Jusdanis

Sitting in a café in Nicosia this spring, I was engaged in a conversation about Cavafy with two colleagues from the University of Cyprus. One of them complained about the market saturation with Cavafy, arguing that the Alexandrian poet was overrated and did not deserve the fifteen or so English translations of his work. What is reputation, I asked? How can we measure poetic quality and all agree? Isn’t fame the product of what people say about a particular artist?

My mind went to this conversation a month later, when I picked up Dan Georgakas’s My Detroit. Growing Up Greek and American in Motor City, because Georgakas, a labor historian and film critic, had discovered Cavafy in his youth. Trying to figure out what it means to be Greek in America, the young Georgakas read books that offered “romanticized but joyous evocations of Greece,” texts like The Colossus of Maroussi by Henry Miller and The Alexandrian Quartet by Lawrence Durrell. But it was Cavafy who furnished Georgakas with maps for his life. “Far more powerful,” he says, “were the words and images I found in the poetry of C. P. Cavafy.”

In a sense Georgakas’s remarks provide a possible answer to my colleague’s protests about Cavafy’s reputation. Cavafy is what people say about him. What is interesting about Georgakas’s experience is how far the poet’s reputation had traveled among some Greek Americans in the 1960s. What I did not know when I first read My Detroit, however, is the extent of the influence that the Alexandrian poet had exerted over a budding writer from a distant end of the Hellenic diaspora. Some Greek Americans were reading Cavafy in the United States decades before Cavafy had become a global poet, before his reputation had become inflated.

“I was astounded by reading Cavafy,” Georgakas wrote to me. “He had more impact on me than any other poet I had every read. Sure, it was the Greek context but what he was saying seemed to apply directly to my Detroit of the 1960s.” This astonishing sentence shows not only Cavafy’s influence on the Greek American author and activist but also the convergence of two diasporic ways of life. What Georgakas had found particularly insightful was Cavafy’s idea of the city, namely that you take it wherever you go. He took the general symbolism of Cavafy’s poem and applied it to his own town and a center of Greek life in the United States. Detroit pursued Georgakas wherever he went in the way that Alexandria had followed Cavafy.

In other words, in Cavafy’s famous poem, “The City,” Georgakas saw a metaphor for his own birthplace. “This was a time many of us were thinking of leaving [Detroit] and becoming expatriates,” he said in the letter. “Others accepted their civic baggage, but believed they had found a location better suited to their talents and temperaments. But what was the city they carried with them? That I carried?”

Countless readers have attempted to answer this question for themselves. But unlike many of these readers, Georgakas followed a most unorthodox path in his attempt to grasp Cavafy’s import. Rather than simply “reading” Cavafy he acted physically upon his prized translation of the Alexandrian poet. Like a person creating a scrapbook, Georgakas, for his own personal consumption, wrote commentary and pasted pictures and cuttings directly on his Cavafy, endowing the poems with paratextual meaning. He was engaged in what theorists of translation call “intersemiotic” interpretation, a form of reading that goes from a set of verbal signs to a set of nonverbal signs, rather than from one language to another. “I identified so closely with him [Cavafy] that I pasted photographs and newspaper account of myself, my friends, and my city on various pages of my copy of The Complete Poems.”

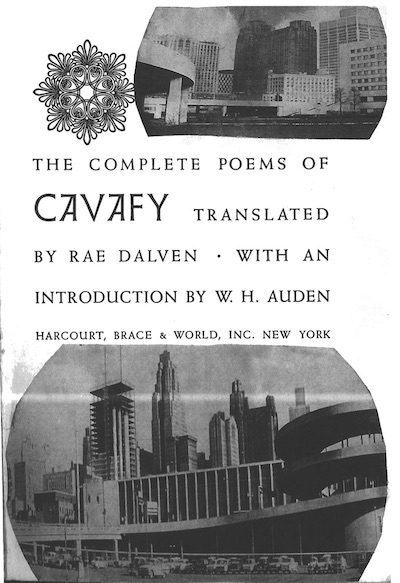

The book—his Cavafy—in which Georgakas glued pictures, advertisements, and press accounts was the 1961 translation of Cavafy’s oeuvre by Rae Dalven, which included the famous introduction by W. H. Auden. Before the appearance of the popular translation by Edmund Keeley and Phillip Sherrard in 1975, this text served as the most easily accessible rendition of Cavafy in English.

Georgakas’s “pasteups” represent his own personal, idiosyncratic reflection on his city via Cavafy’s verses. Georgakas’s Cavafy then is a palimpsest–pictures of cityscapes, advertisements, sketches of city views, various markings and comments—pasted or written on Dalven’s translation of the original, which in itself contains various layers of Greek history. Interpretations upon interpretations upon interpretations. In its archaeology this project is very Cavafian, though a project he could never have imagined. Rather than digging into the past, however, Georgakas pointed to the future by adding further deposits of graphic meaning.

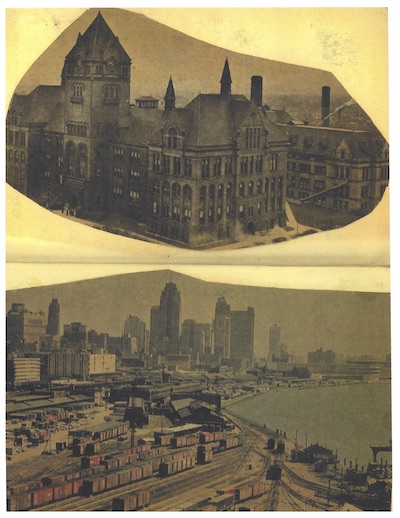

As you open Georgakas’s Cavafy, you see a double photo pasted on the reverse side of the cover, showing the building “Old Main, the old centerpiece of Wayne State University which I attended. Had so many classes there.” The other picture is of Detroit’s skyline seen from the harbor, with views of shipping containers, railway cars, and tracks. Both shots invoke departures, so to speak—the education that took Georgakas away from his working-class beginnings into assimilation and globalization and the trains and ships that physically carried him away from Detroit to Greece and elsewhere.

Georgakas left Detroit because his dreams outgrew the city. “My artistic ambitions,” he says in My Detroit, “baffled my family.” His grandfather feared that Georgakas “would get involved in an eccentric lifestyle and meet unscrupulous people” while his mother accepted his intellectual pursuits only because they were valued by Americans. By becoming a public intellectual and social activist, did Georgakas lose Detroit or did he, as he implied in his note to me, carry it with him all his life?

Unlike Georgakas, who traveled widely, after 1905 Cavafy never left Alexandria until 1932 when he went to Athens for surgery. But he had lost everything else dear to him—his social status, his family wealth, his closest friends, and every family member except for his brother John. The only thing left was his Alexandria: not Alexandria as a real city–Joyce’s Dublin–but an imaginative recreation. There are few references to actual streets, shops, or squares of Alexandria in his poetry, his beloved city having been converted into a metaphor.

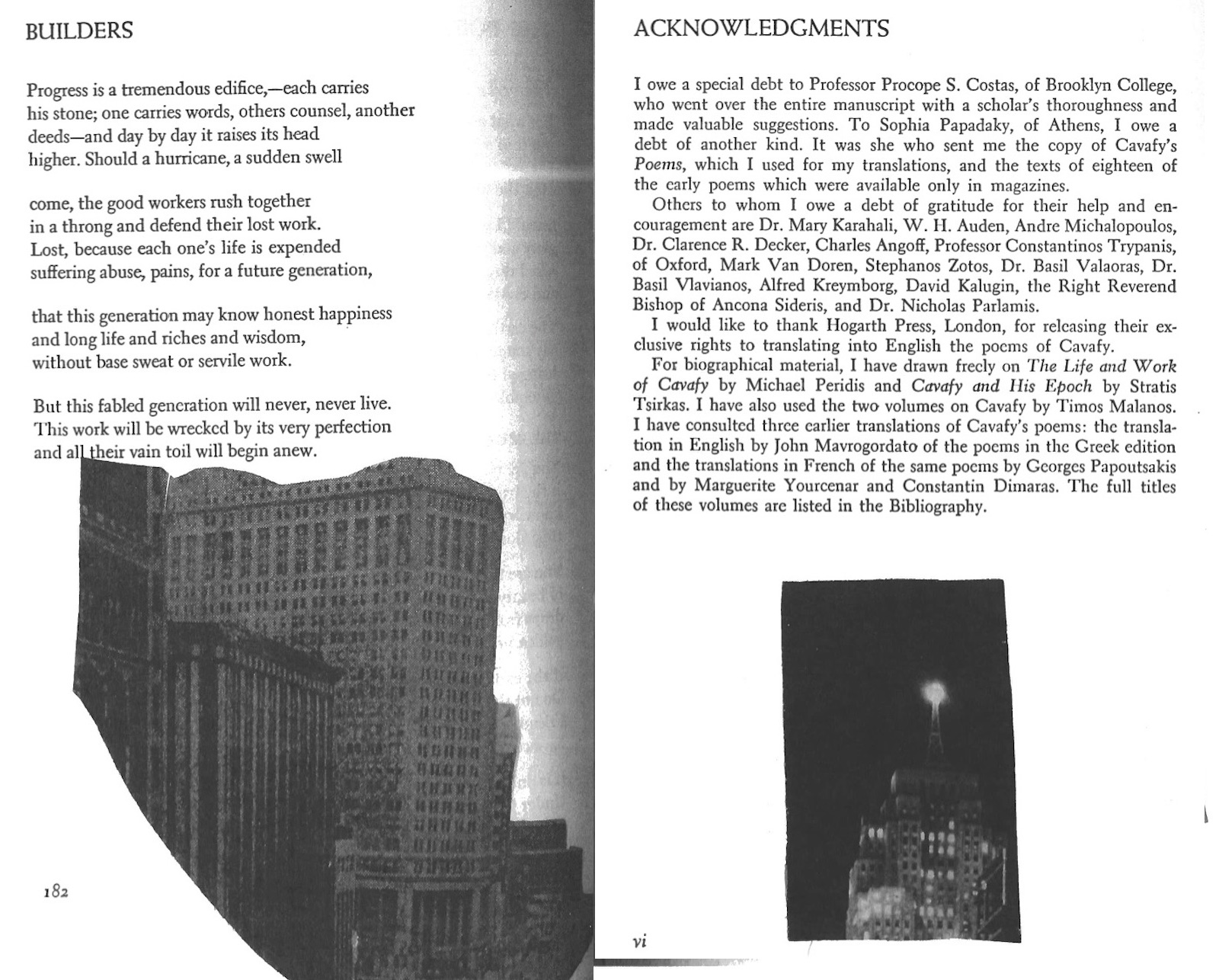

But Georgakas made his own city real. On the front page above and below the title of the Dalven translation, Georgakas placed two pictures of the Detroit skyline, giving a sense of vibrancy and optimism, of modernist structures reaching up to the sky in triumph. And below the Acknowledgments we have a picture of the Penobscot Building, “the tallest in Detroit,” with a red beacon “flashing on and off, esp. striking at night.”

To Cavafy Alexandria signified both people and places:

I came out to the balcony –

came out to change my thoughts at least by looking at

a little of the city I loved,

a little movement on the street, and in the shops.

(“In the Evening”)

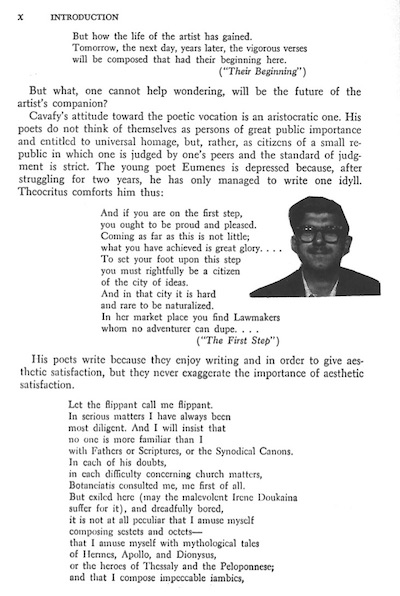

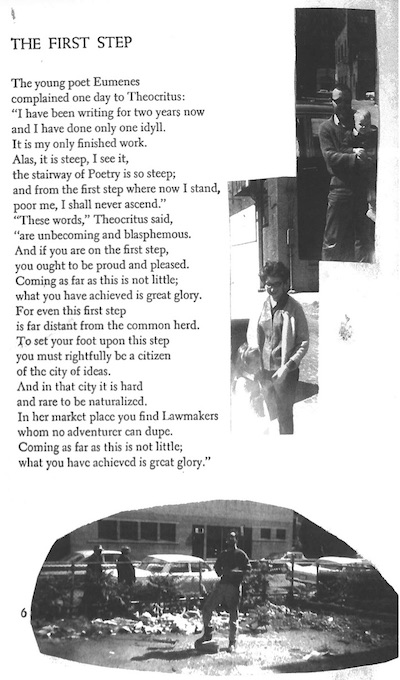

In Georgakas’s Detroit, too, people endow the actual buildings, streets, and shops with meaning. So early in Auden’s Introduction, Georgakas pasted a picture of himself, as a student perhaps, right next to Auden’s comments on Cavafy’s “The First Step.” You should be proud, Cavafy says, with the first steps you have taken, for now “you must rightfully be a citizen / of the city of ideas.” A shoulder shot of a Georgakas, with short dark hair, a mustache, wide-brimmed glasses and a callow smile. Is this a passport photo? Is he grinning because he is hopeful about his first trip to Greece? His ambition to become a public intellectual, to enter the “city of ideas?”

Two pages later and still within the Introduction, next to Auden’s discussion of “Philhellene,” we see a shot of Georgakas’s friend Carl Schurer, an artist, who left Detroit to live in Rhodes for several years. Schurer sits in a car with dark glasses, looking out to the left, with his arm folded on the rolled-down window. Another figure turns toward us as well, to his right, but we can’t make out the face. Schurer must have been an important friend to deserve such space in this special book; we see three more pictures of him with his wife and children later on.

This intimacy would not have been possible for Cavafy because after middle age he gave up on love in his pursuit of greatness as a world poet. Did Georgakas know this about Cavafy? Would he have cared that his illustrious poet had no close friends in his adulthood? Did this matter that Cavafy was self-centered and callously self-promoting, that he used others in order to publicize his name?

For Georgakas, Schurer could have represented the philhellene of Cavafy’s poem who asserts “So, we are not un-Greek,” Cavafy. Who is a Greek and who is an American? After all, up Dan Georgakas’s My Detroit is Growing Up Greek and American in Motor City. And the final lines of his memoir are: “Such was my Detroit. My American horio.” It takes a village, I suppose, to tell you about the world. But you have to leave the village because you feel its asphyxiating hold on you even though you fear you can’t breathe without it.

On the page facing Schurer is another photo of Georgakas standing against a wall plastered with posters; he is in an alley across from the Unstabled, the famed coffeehouse and theater and jazz venue that played such an important part in his life and that marked his entry into American intellectual life and his exit from his immigrant past. In his memoir, Georgakas recounts his involvement in this “joint,” the plays he helped stage, the jazz concerts, the presentations of leading authors. He is proud that it was a “racially integrated theater company” and produced such leading entertainers as the comedian Lily Tomlin. So perhaps although he believed he left Detroit, he had actually brought it with him, as Cavafy had done in “The City.”

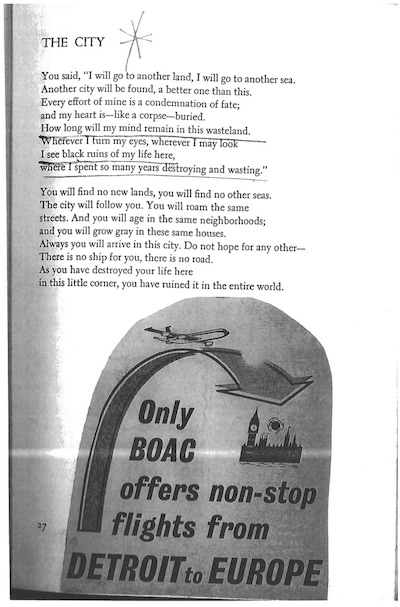

Unlike all the other poems in the translation, Georgakas identified “The City” prominently with an asterisk in pencil over the tile; he also underlined some verses: “How long will my mind remain in this wasteland. / Wherever I turn my eyes, wherever I may look / I see black ruins of my life here, / where I spent so many years destroying and wasting.” Is this the way Georgakas felt during his youth? Did he want to leave Detroit because he feared himself wasting away? Below the text, he pasted an old advertisement from the British Overseas Airlines Corporation (BOAC), the previous name of British Airways. “Only BOAC offers non-stop flights from DETROIT to EUROPE,” the ad declares with a bold arrow taking you from Detroit to the Tower of London. This was a sign, not only of Georgakas’s thirst for travel, but also of his need to escape his Alexandria.

He felt this desire to depart upon his return from his first trip to Greece. Taking a taxi from the airport down the Ford Expressway, he saw the Penobscot Building: its “red globe throbbing amid the downtown skyscrapers; rather than pounding out a welcome, its message seemed more a coded warning that all was not well.” For years he and his friends spoke about leaving Detroit, and Georgakas wondered if Greece was not a better choice for him. “Didn’t Cavafy inspire me more than any other poet?” As he continued down the highway, “Detroit had never seemed quite so dismal.” It appears that Detroit began to signify for him “The Walls” of Cavafy’s poem, of being closed in, dying of limited choices:

And now I sit here despairing,

I think of nothing else: this fate gnaws at my mind;

for I had many things to do outside.

Yet, even if he abandoned Detroit, the city did not abandon him. Most of the pictures in his Cavafy book are cityscapes, from crowds on the street to shots of the “Olympia indoor stadium, the home of the Detroit Red Wings and operated by Greeks.”

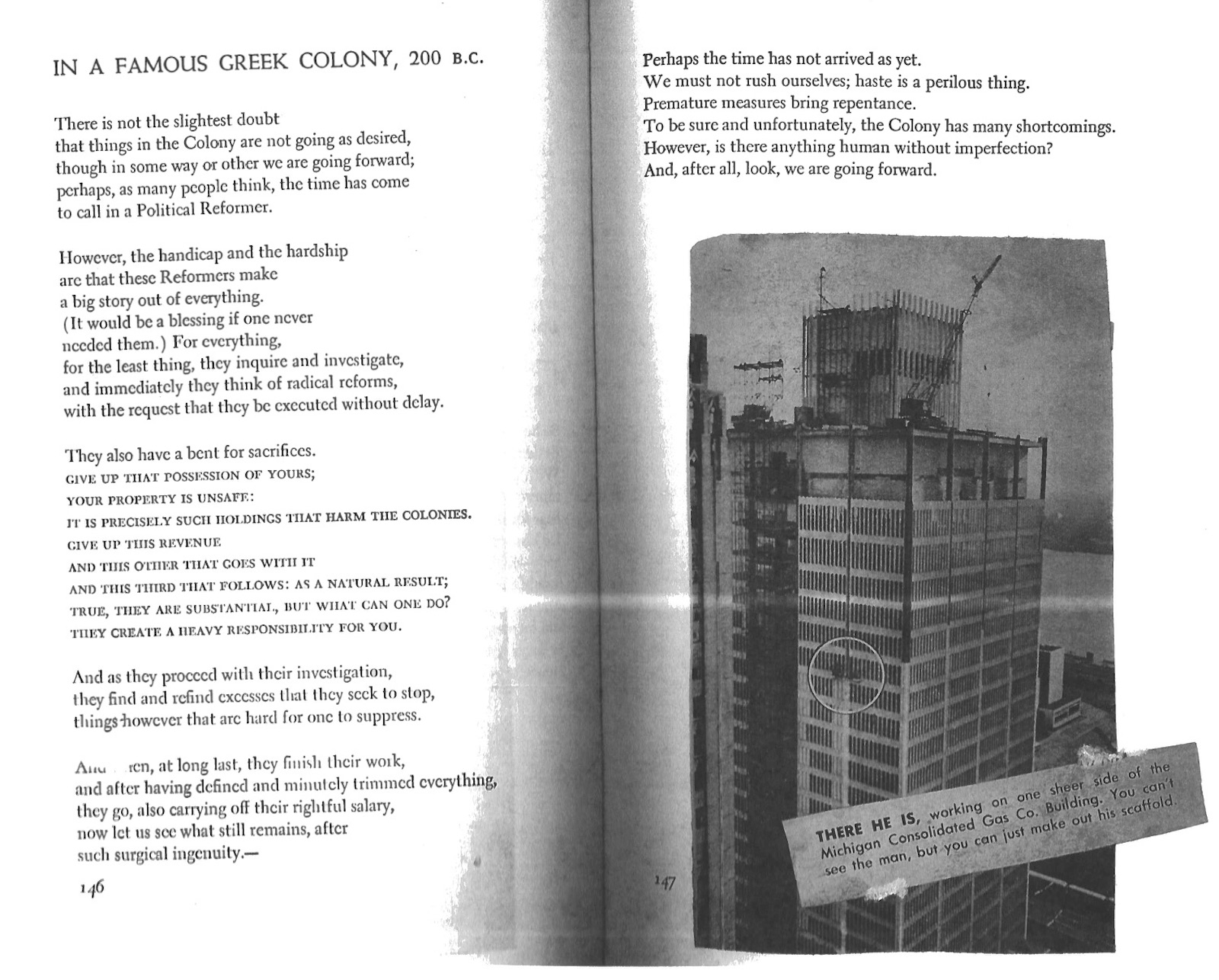

Equally important, it was Detroit that taught him of the importance of the fight for social justice, a passion that comes out strongly in the picture Georgakas paired with the poem “In a Famous Greek Colony, 200 B.C.,” which deals with corruption, cynicism, and self-deception amongst the elites of a city. While its citizens acknowledge that “things in the Colony are not going as desired,” they satisfy themselves with clichés about the status quo. “And after all, look, we are going forward.”

Immediately below the text Georgakas pasted a shot of a skyscraper and drew a circle around a scaffold high up on the building. Across the building he pasted the following caption that must have appeared with the picture in a newspaper: “THERE HE IS, WORKING on one sheer side of the Michigan Consolidated Gas. Co Building. You can’t see the man but you can just make out his scaffold.” The lonely individual works away, doing his job while the city languishes. In a personal note Georgakas characterized this picture as “Homage to the working class.” Though the photo appears with “In a Famous Greek Colony, 200 B.C., the worker also evokes the uncelebrated hero from Cavafy’s “Thermopylae,” who does his duty even if he knows no one will remember him:

Honor to those who in their lives

are committed and guard their Thermopylae.

Never stirring from duty;

just and upright in all their deeds.

Just as Cavafy celebrated the nameless heroes in his poem, Georgakas brought attention to the faceless worker.

The social activism Georgakas was engaged in also differentiated him from Cavafy, who, people complained, was not interested in political affairs. Timos Malanos, a former friend of Cavafy’s, says that the poet often said that “contemporary affairs did not inspire him.” Although Cavafy wrote movingly about the fall of civilizations, palace intrigues, and political assassinations in antiquity, the politics of his day, World War I, or the Asia Minor catastrophe do not appear as subjects in his poems.

Georgakas’s discovery of Cavafy early in his career and his multidimensional engagement with the poet’s work perhaps provide another answer to my Cypriot colleague’s objections about the undeserved expansion of Cavafy’s reputation. That Cavafy could stir the imagination of a Greek American intellectual and provide him with the metaphors to understand his life shows the extent of his reach. By the same token, Georgakas’s palimpsest is an homage to the Alexandrian poet. Although by now many painters and sculptors have interpreted Cavafy, it seems that Georgakas may have been one of the first to approach the poet with pictures rather than with words.

Gregory Jusdanis teaches Modern Greek and comparative literature at The Ohio State University and is author of The Poetics of Cavafy: Eroticism, Textuality, History (1987); Belated Modernity and Aesthetic Culture: Inventing National Literature (1991); The Necessary Nation (2001); Fiction Agonistes: In Defense of Literature (2010); and A Tremendous Thing: Friendship from the Iliad to the Internet (2014).

Author’s note : The existence of Georgakas’s personal and idiosyncratic project on Cavafy was told to me by Yiorgos Anagnostou who then invited me to write about it.

Works Cited

C. P. Cavafy. 1968. The Complete Poems of Cavafy. Translated by Rae Dalven. Introduction by W. H. Auden. New York: HBJ.

Georgakas, Dan. 2006. My Detroit. Growing Up Greek and American in Motor City. New York: Pella.

Editor’s note: Image gallery of Georgakas’s additional pasteups