The Diaspora Research and Immigration Initiative (DRIMMI): Archival Research on Greek Immigration and Diaspora in Thessaloniki, Greece

In 2017, the Diaspora Research and Immigration Initiative (DRIMMI)1 conducted a preliminary study on Thessaloniki’s state and private archives and museums with the aim of identifying tangible and intangible material regarding twentieth century Greek immigration and diaspora. Our research was only preliminary at the time, with the goal of examining the availability of relevant resources in the city’s archives. We also wanted to reflect on the prospect of using such material in a future museum of Greek immigration and diaspora given that such museum does not currently exist in Greece. Our team’s broader scope was to foster the public understanding of twentieth century Greek migrations, but also to generate possibilities for the creation of a Greek immigration and diaspora museum in the country.

The motivation for our work emanates from a gap in both the academic and the public sphere in Greece regarding the mass emigrations that shaped Greek society during the twentieth century. This phenomenon remains significantly understudied and underrepresented. Unlike many countries in Europe and north America, Greece lacks an academic institution devoted to researching, documenting, and disseminating knowledge about twentieth century Greek migration and diasporas.2 Greece does not have a museum dedicated to the topic either, an absence which prevents us from placing the diaspora as an integral component of Greek history. Because of this significant gap, knowledge about the topic is largely based on stereotypical representations of Greek immigrants and diasporic subjects. This situation makes the work of our team extremely important and timely.

Considering that similar research endeavors had never been launched in Thessaloniki’s archives before, our work was the first step to fill a vital void which exists at the intersection of immigration, modern Greek diaspora, and material culture studies. The study of immigration and diaspora through the lens of material culture was an issue of paramount importance for our project. Βy adopting concepts originating in material culture, such as Arjun Appadurai’s social life of things,3 we wanted to illustrate the shifting meanings of objects depending on their interactions with individuals—the owners of artifacts, their families, and their communities—as well as the context of their use, in household environments, or as keepsakes from the mother country. Approaching artifacts as objects intimately connected with people’s lived experiences and identities, our overall goal was to illustrate the complex trajectories and identities of people who migrate and settle in new lands. At the same time, by borrowing the concept of transnationalism from immigration and diaspora studies, we wanted to introduce a framework of analysis that links the originating and the receiving societies of immigrants and diaspora populations as well as to conceptualize heritage, and history beyond national borders.

In general terms, the categories of material we located in Thessaloniki’s archives and museums vary. We found documents, manuscripts, objects, works of art, photographs, audiovisual material, periodical publications, and newspapers. We also collected a few oral histories from individuals connected with the immigration experience. Though the number of archives we visited and the testimonies we documented is extensive,4 for the purposes of this report we will only focus on some of our most representative findings.

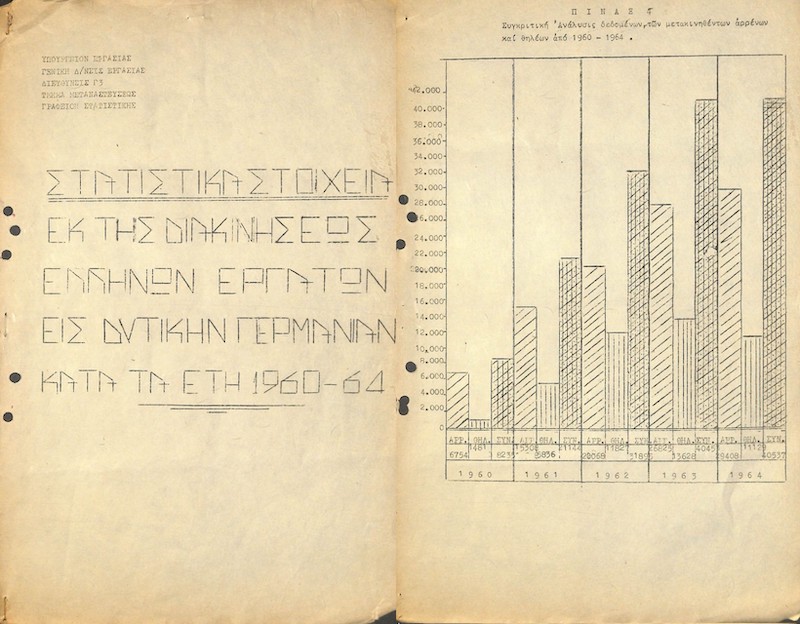

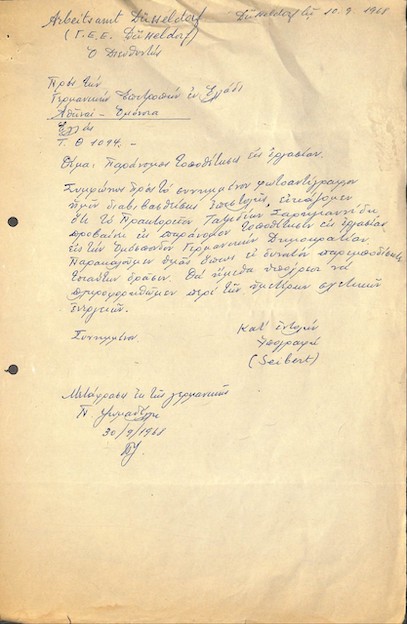

In the General State Archives – Historical Archives of Macedonia (GAK-IAM) we discovered documents which outline the sociopolitical framework of post-WWII emigration of Greek workers to Germany. Some examples include bilateral contracts between Greece and Germany that describe the working conditions of immigrants in the receiving country, statistical data related to the mobility of Greek workers—women and men—and documents of Greek official authorities about undocumented migration to Germany.

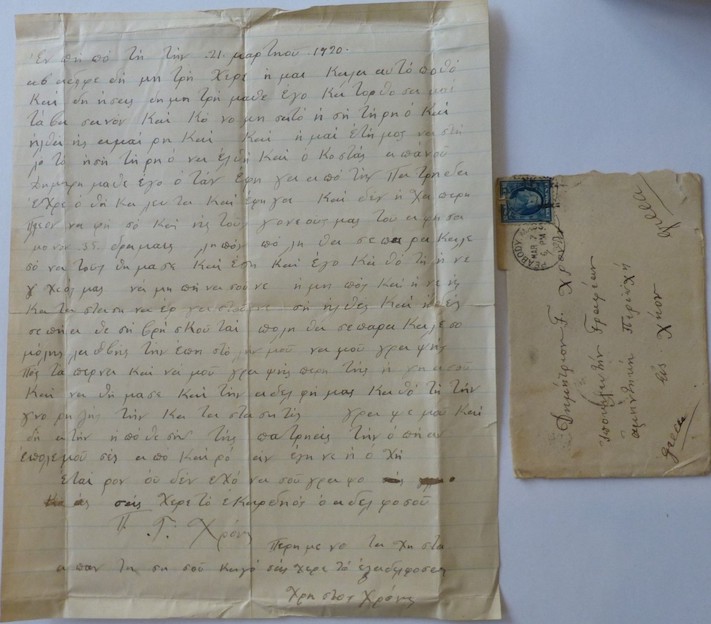

In Thessaloniki’s Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive – National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA-ΜΙΕΤ) we found an important corpus of personal archives with correspondence between U.S. Greek immigrants and their families in Greece. Such testimonies demonstrate, among other issues, the financially difficult living conditions both in the origin and the host countries, as well as the ways in which the immigrants placed themselves in-between the United States and Greece. There are also examples of early twentieth century letters, in which immigrants express their desire to return home after they earn money in the United States, a desire which counters the dominant story of immigration as assimilation into the United States and the fulfillment of the American Dream. The letter of Panagiotis Hronis, a resident of Peabody, Massachusetts, to his brother in Chios, Greece illustrates this orientation.

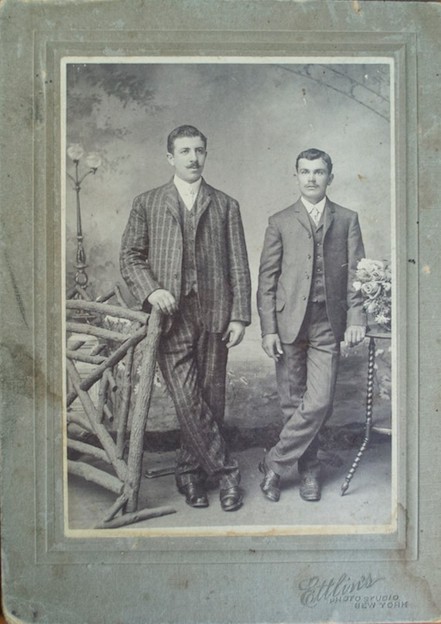

In the archives of Aristotle University,5 we found twentieth century periodical publications (newspapers and magazines) associated with a broad range of Greek communities in Europe, the United States, Australia, and Egypt, among others. In the Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace we found family heirlooms of Greek immigrants in the United States, some of which were sent to their relatives in Greece as gifts. Last but not least, in the Kalemkeris Museum of Photography we found portraits of Greek American families taken in photography studios of Boston and New York, amongst others, probably in the first half of the twentieth century.

According to our preliminary analysis, the collections we identified consist of personal narratives, and illustrate the historical, socioeconomic, and political events which shape the experiences of immigrants and diaspora people. This is important, as any future conceptual and spatial exhibition design project must generate concepts that consider the personal experiences of immigration in the macro-historical context, i.e., the immigration of post-WWII foreign migrant workers (“Gastarbeiter”) in Germany in the context of the country’s industrialization, class hierarchies and labor struggles as well as poverty in Greece. Regarding the documented artifacts, our observations point to the transnationalism of migrant subjects, that is their connection with both the originating and the receiving countries, as well as their bicultural identities. In our view, concepts such as transnationalism and cultural mixing are aspects of the experience that should be highlighted in a museum of immigration and diaspora, or even be placed at the center of its conception.

Although Thessaloniki was our initial case study, we understand that our work needs to expand into other cities and regions of Greece, but also archives hosting Greek diaspora material outside the country. Such collaborations with archives abroad can prove crucial on expanding the scope of DRIMMI. At the same time, attracting individuals who would be interested in contributing by donating materials would also be helpful. In this manner we want to follow the paradigm of migration museums in Europe and the United States, the establishment of which involved a transnational circulation of testimonies, but also a cross-border collaboration between archives, museum professionals, and academics. Although the continuation of our research is contingent upon the availability of funds, we hope to build a set of networks within and outside Greece that will enable us to reach our goals soon. The importance of understanding Greek migration and diaspora in both their historical and contemporary frameworks in Greece, make the continuation of our project all the more urgent.

We would like to take the opportunity in this essay to directly address the Greek people in the diaspora and invite them to embrace and support our initiative. The benefits of such a project to Greek communities abroad are multiple. Their endorsement of an immigration and diaspora museum in Greece would recognize their historical and contemporary contributions to their historical homeland. Their support would also contribute to the mutual understanding between the Greeks of the diaspora and the Greeks in Greece. In this manner, Greek communities abroad will be entering a mutually beneficial dialogue with their counterparts in Greece, being in a position to share their experiences and express their perspectives, while strengthening their links with Greek society. Considering that museums should be founded and informed by systematic feedback from their source communities, establishing connections between Greece and its diasporas is pivotal in the planning stages of an immigration and diaspora museum.

Matoula Scaltsa

is an Emeritus Professor of Art History & Museology, Academic Head of

the MA Program in Museology-Cultural Management, School of Architecture,

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and University of Western Macedonia.

Angeliki Tsiotinou is a PhD candidate in Museology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Her work explores the museum representations of migration, focusing on Greek America as a case study. She recently organized a seminar for the students of the “Museology-Cultural Management” MA Program, in which she spoke about museum representations and (Greek) immigration to the United States.

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank the General State Archives – Historical Archives of

Macedonia (GAK-IAM), the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive –

National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA-ΜΙΕΤ), Department of

Thessaloniki, and the Kalemkeris Museum of Photography for granting us

permission to publish the archival material.

Notes

1. DRIMMI is an interdisciplinary body of individuals, a critical nexus for research on Greek Immigration, Diaspora and the Refuge. For more information visit

2. Some exceptions are the Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) which has a cluster on Migration, the Center of Intercultural & Migration Studies at the University of Crete, and the Institute for the Study of Migration and Diaspora in the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (EMMEDIA). These institutes, however, do not emphasize the study of migration via tangible and intangible evidence such as keepsakes that people may take with them when immigrating, or everyday life objects associated with their settlement in the new country.

3. Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

4. The archives we visited include the General State Archives-Historical Archives of Macedonia (GAK-IAM), the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive-National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA-MIET), the archives of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh), the Historical Archive of YMCA, Thessaloniki History Center, the Municipal Library of Thessaloniki, the ‘Manos Malamidis’ Historical Archive of Thessaloniki. The list of museums includes the Folklife and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace, the Kalemkeris Museum of Photography, the War Museum of Thessaloniki, MOMus Art museums, Thessaloniki Cinema Museum and Cinematheque, and the Teloglion Fine Arts Foundation AUTh.

5. Including the Historical Archive of the History Department of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh) , and the Archives of AUTh’s Central Library.

Cover Image Credits: DRIMMI's logo was designed by Post-Spectacular Office, a narrative-driven design office based in Thessaloniki, Greece.