Mapping Greek Businesses in Toronto, 1910s to 1960s:

A Digital Humanities Project

by Alexandros Balasis

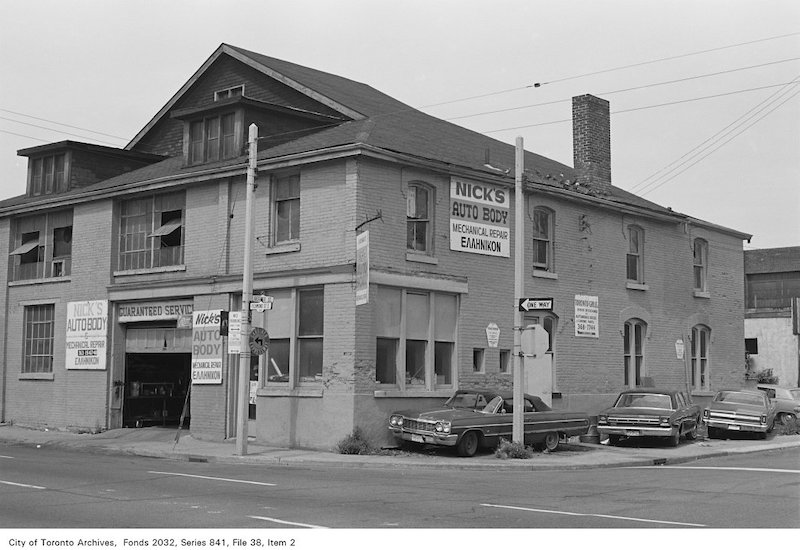

(City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 2032, Series 841, File 38, Item 2).

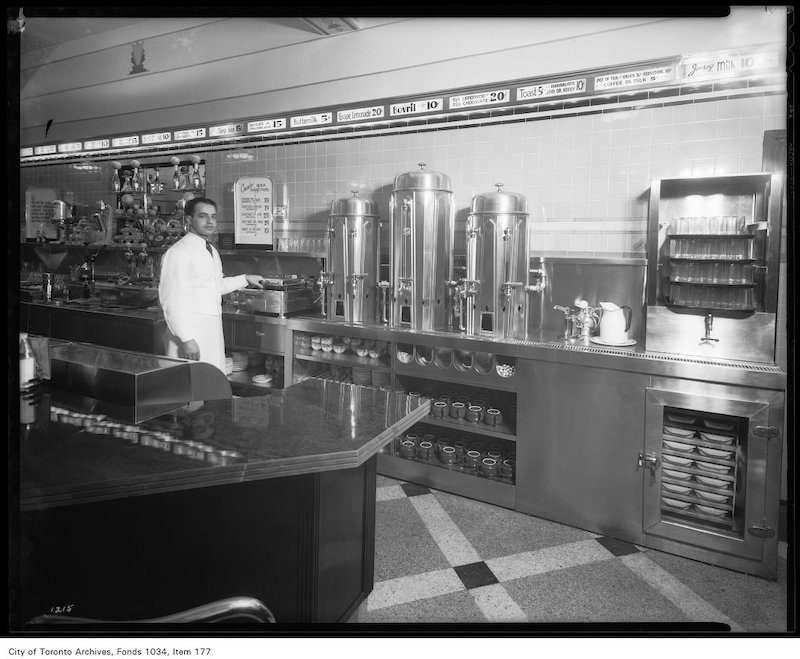

In his 1922 Greek Canadian Guide, Hercules Papamanolis, editor of the first Greek newspaper published in Canada, described the country to prospective Greek immigrants, noting that “the Greeks in Canada are mostly engaged in confectioneries, restaurants, cinemas, billiard halls, small restaurants, and hat cleaning businesses.” [1] Indeed, in the early twentieth century, Greek immigrants established themselves in a range of small businesses, with restaurants playing a particularly central role. From this period, marked by the violent attacks on Greek-owned restaurants during the 1918 anti-Greek riots in Toronto—fueled by hostility over Greece’s perceived pro-German stance—to the shared experience of post-Second World War immigrants working as dishwashers in Greek restaurants to earn their first dollars in Canada, food services emerged as one of the most visible and prominent sectors of Greek business in the city. However, emphasizing restaurant ownership as the defining feature of Greek entrepreneurial history in Toronto overlooks the broader landscape of Greek-owned enterprises beyond food services, and their role in sectors such as retail, personal services, and entertainment. It also draws attention away from the socioeconomic mobility of Greek entrepreneurs, their evolving geographic distribution, and their contributions to Toronto’s economic landscape.

To foreground the history and diversity of Greek entrepreneurship, the Greek Businesses in Toronto Mapping Project documents the geographic distribution and sectoral diversity of Greek-owned businesses in the city between the 1910s and the 1960s. The project’s primary objective is to pinpoint the locations of these businesses, record the names of their owners, and, whenever possible, provide pictures of the businesses as well as related oral histories utilizing materials collected by the Hellenic Heritage Foundation Greek Canadian Archives (HHF GCA). By doing so, the project challenges the prevailing association of Greek immigrants with restaurant ownership and explores the full extent of their occupations and economic contributions. Also, rather than adopting a celebratory view that frames Greek immigrants as inherently entrepreneurial, [2] the project offers a more nuanced account of Greek economic life in Toronto, one that acknowledges both success and failure, mobility and marginalization.

This digital humanities project builds upon rich knowledge of spatial analysis in migration studies. As early as 2002, researchers used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze immigrant settlement patterns in New York City. [3] Regarding Greek immigration, historians Kostis Kourelis and David Pettegrew mapped immigrants’ distribution in Philadelphia’s Greek neighbourhoods, using census data between 1900 and 1930 as well as historical maps, revealing diverse patterns of settlement, employment, and assimilation. [4] Similarly, the Immigrec: Stories of Greek Immigration to Canada project created a group of maps related to Greek immigrants to Canada from the 1950s to the 1970s, featuring Greek shops in Montreal, Greek households with telephone lines, and locations referenced by their interviewees. [5] In Toronto, other notable digital history projects have focused on the vital role of immigrant construction workers in shaping the postwar city and the role of food in Italian-Canadian cultural identity through the establishment of key food businesses. [6] This project is the first to create an extensive and detailed dataset, complemented by an interactive map, that illustrates the presence and activity of Greek businesses in Toronto for seven decades.

Gathering the Data: Sources and Methodology

To compile the dataset of Greek-owned businesses in Toronto I employed rare archival material from the HHF GCA. I drew from Hercules Papamanolis’s 1922 guide, which highlights Greek businesses in major Canadian urban centers. [7] The 1930 and the 1937 Yearbooks of the Greek Community of Toronto features a directory of its members many of whom owned businesses. [8] The 1942 George Vlassis’s book on the history of Greeks in Canada lists operating businesses in Canadian cities with its second edition updating the catalogue. [9]

The second set of our major sources were local city and Greek Canadian newspapers. For the 1910s businesses, the Toronto Daily Star and The Evening Telegram provide valuable information in their extensive coverage of the anti-Greek riot of 1918, identifying the names of damaged businesses and their owners. [10] For later entries, I researched the Toronto-based Greek-language press, which hosted advertisements stating the names of the businesses and their owners as well as their addresses. Among the newspapers used were the Hellenic Tribune (Ελληνικόν Βήμα), first published in 1958, [11] Hellenic Hestia (Ελληνική Εστία), a monthly publication from 1967 to 1969, [12] New Times (Νέοι Καιροί) and New World(Νέος Κόσμος) both starting publication in 1967. [13]

Finally, city directories and supporting media also played a vital role in this project. To verify business ownership, the above sources were cross-referenced with Might’s Greater Toronto City Directory. [14] Oral interviews with proprietors, employees, or clients were retrieved from the HHF GCA Digital Portal and referenced businesses were linked to those in the dataset. Photographs were sourced from the City of Toronto Archives, the Toronto Public Library Digital Archive, the Archives of Ontario, and the HHF GCA collections.

A key challenge in identifying Greek-owned businesses was the reliability of sources, given that they often listed businesses that were not necessarily Greek-owned. To address this, the project prioritized collecting business addresses and cross-referencing them with multiple sources. This process helped to correct errors and inconsistencies. Moreover, the question emerges about how Greek businesses were defined for this project. A business was considered Greek if it appeared in Greek directories or advertised in Greek-language newspapers. This meant that it demonstrably catered to a Greek clientele. While ownership was an important criterion, the project acknowledges that some businesses played a significant role in the Greek community even if they were not exclusively Greek-owned. At the same time, determining the operational time frame of each business relates to the limitations of historical sources. Rather than providing a continuous record of business operations, the dataset represents a snapshot in time. Businesses were categorized by decade based on their appearance in at least one source from that period. If a business was found in records from multiple decades, it was categorized accordingly in each relevant time frame.

The Interactive Map

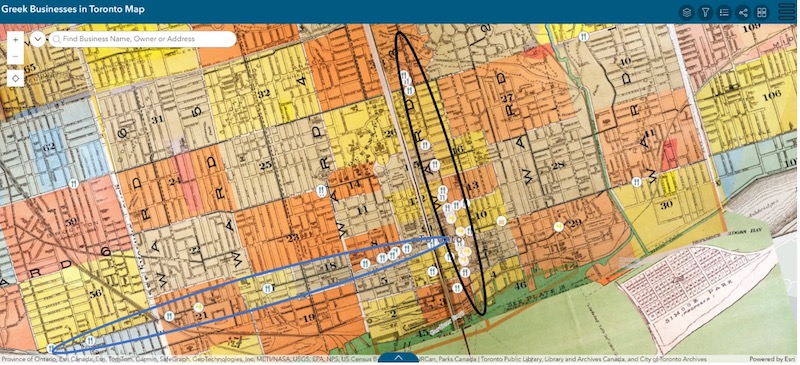

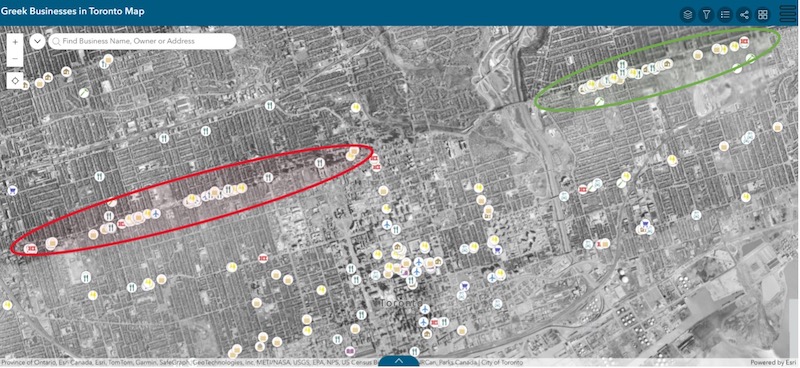

To visualize the data gathered, this project utilized ArcGIS Online to create an interactive map. The map allows users to explore businesses by decade, displayed on historical base maps—fire insurance maps for the 1910s and 1920s, and aerial photographs from the 1930s onward. More than 900 locations were created across seven decades. Clicking on a business point opens a pop-up with details such as business name, address, owner, industry, decade in operation, source, notes, and media like photographs or oral interviews.

Users can filter by industry, decade, and media availability. A search function enables searches by business name, owner, or address. A data table allows access to the raw data available for the selected decade. Additional tools include a legend highlighting the top 10 industries per layer and a function that allows users to see Greek businesses that were historically located near their current location.

The Evolution of Greek Entrepreneurship

Greek immigration to Canada in the early twentieth century was an offshoot of immigration to the United States. During those “boom years of immigration” and between 1900 and 1907, not more than 2,500 Greeks reached Canada. [15] Most originated from the Peloponnese, and having initially migrated to the United States, headed to Canada after already achieving a level of acculturation. [16] The community started growing after 1905, as more women and children arrived, reaching around 3,500 people by 1911 and nearly 6,000 by 1912. Despite disruptions caused by the Balkan Wars and World War I, the Greek population in Canada continued to rise, surpassing 9,000 by 1931. [17] Most immigrants settled in Toronto and Montreal. They found employment in labour-intensive sectors, working in businesses such as shoeshine parlours and restaurants. By the 1910s, Greek entrepreneurship was emerging in Toronto, with the establishment of a substantial body of businesses, 58 enterprises recorded in the database.

Early Greek settlers in Canada often helped their compatriots find work in their businesses, but there have been reports since as early as 1909 that Greeks have been exploited by their co-villagers in the context of the padrone system. [18] Food services dominated, which constituted nearly 80% of all Greek businesses, [19] followed by shoeshine parlours and hat cleaners. The latter occupied the public’s attention, because of the instances of exploitation of Greek shoeshine boys under a system of peonage. [20] Geographically, the businesses concentrated heavily along Yonge Street and Queen Street (central venues in downtown Toronto), providing services in high-traffic areas of the city and primarily catering to a broader Canadian clientele.

The 1920s and 1930s saw the consolidation of Greek entrepreneurship in the city, with food services still predominant, while retail [21] and personal and customer services (small businesses) [22] became more prominent. Yonge Street remained the primary commercial hub, but new clusters emerged along Danforth Avenue. The 1930s witnessed continued growth in Greek businesses with food services still prevalent, but entertainment and recreation businesses were emerging as a significant sector, suggesting cultural adaptation of the entrepreneurs and possibly their Greek clientele to the Canadian way of entertainment. While Yonge Street remained important, Bloor Street also gained prominence. The dataset suggests that, up to this point, a few individuals or families were significantly overrepresented, with multiple branches of their stores and venues spanning various sectors. One such individual was Vasileios Karapanagiotis (Bill Karrys), who initially owned shoeshine parlours and later billiards and bowling alleys. The rise of this micro-elite is further evident in the Greek Community leadership before the 1940s, which included, among other businessmen, restaurant owners Nick Speal (Spiliotis) and Peter Bassel, confectionary shop owners Bill Merzanis and Constantinos Voukidis, billiards and bowling alleys owners George Bulucon and Louis Yeotis. [23]

In the 1940s and 1950s, food services remained the backbone of Greek entrepreneurship in Toronto. During the 1940s, Bloor Street’s importance grew. Greek businesses, also, played an active role in supporting the Greek War Relief Fund, [24] which provided aid to Greece during World War II and the Toronto Red Cross campaign, which supported Canadian soldiers. [25] This reflected the immigrants’ continuing connection to their homeland and their efforts to showcase Canadianness. After 1945, Canada was booming at an unprecedented rate and by the end of the 1950s, the economy was well into a new industrial revolution. Immigration provided the much-needed labour, with more than 4 million people arriving until the 1970s. According to the Greek National Centre for Social Research, by 1955, more than 2,000 persons were emigrating to Canada annually. [26] The 1950s marked renewed growth in Greek businesses, coinciding with increased post-war immigration. Food services continued to dominate, but retail trade and personal services displayed a steady presence.

The number of Greek arrivals kept increasing throughout the next decade, reaching 10,000 in 1968 alone. [27] The 1960s represented a transformative period when Greek businesses started reflecting major immigration waves from Greece. Notably, this decade saw a significant shift in industry type according to the collected data: personal and customer services became the leading sectors with food services and retail trade following. Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue surpassed Yonge Street as primary business locations, solidifying Danforth as the cultural heart of the Greek community. Unique to this decade was the greater occupational diversity and socioeconomic advancement within the community, with the emergence of professional and educational services. These businesses not only provided vital employment opportunities but also served as important gathering spots for newcomers. Notably, social mobility became evident as employees like managers, or even dishwashers and cooks, eventually became proprietors of their own establishments.

Based on the available records, if we assume that each business was linked to a family unit of four to five individuals, approximately 10-20% of the Greek population in Toronto was directly connected to the businesses recorded at various points. This suggests that while business ownership was a defining feature of Greek economic activity, a majority of the community earned their living from different types of labour. [28] However, this estimate is not exact, as our data is drawn from limited sources. The actual number of businesses may have been higher, and the total Greek population in Toronto, as recorded by Canadian censuses, is still being processed as part of this project.

Conclusion

The pattern is clear, over seven decades food services remained the dominant sector, making up more than half of all Greek businesses. This concentration was driven by chain migration and strong kinship networks, with many restaurant owners relying on family labour. With Greeks operating a significant number of restaurants, confectioneries, tea rooms, and grills, one could confidently say that Greeks fed Toronto. While Greek men typically lacked cooking skills upon arrival, especially for American-style food—which was the only type of food served in Greek-owned restaurants until the late 1960s—these skills were often acquired through informal networks due to the presence of already established Greek businesses. [29] As one can, also, see by their names, these businesses did not focus on showcasing Greek identity. [30] However, while food services were the majority, the dataset reveals a broader range of economic activities previously overlooked, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, challenging the stereotype of Greeks solely as restaurant owners and highlighting their entrepreneurial ventures across various sectors.

Geographically, they were mainly concentrated along key streets, with Yonge Street serving as the primary commercial hub from the 1910s through the 1950s. By the 1960s, however, Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue emerged as new centers for Greek-owned businesses, contributing to the creation of Greek neighbourhoods.

Furthermore, there was a growing spread of Greek businesses beyond the city center, particularly along the emerging subway lines, reflecting efforts to tap into new customer bases, while succeeding in deeper integration into Toronto’s economy. This further indicates that many businesses were not solely serving a Greek clientele but a broader customer base. The project also underlines the emergence of professionals like lawyers, accountants and doctors in the 1960s, reflecting increased social mobility and signifying a shift from low-wage, service-oriented jobs to more established and socially respected occupations.

Historical research is always a negotiation between what is recorded and what remains elusive. While many businesses were documented in directories and advertisements, others—such as mobile vendors or street food sellers—operated informally, leaving little archival trace. Moreover, some businesses were overrepresented in the record because they were carefully promoted or linked to prominent community figures, such as doctors and lawyers, who often served on the boards of Greek community organizations.

Ultimately, the project contributes to broader discussions in urban studies, immigration studies, and the understanding of the immigrant experience in Toronto, while emphasizing the significance of a digital humanities project for the Greek community in the city. This is why seeks to engage in ongoing conversations with the Greek community of Toronto, acting as a tool for producing and strengthening occupational memory not just as a means of preserving its cultural heritage, but also as an opportunity to critically examine how this heritage has been constructed, remembered, and sometimes silenced. Significantly, the project enables the community’s active participation in its enhancement. By providing a form for users to share their stories, it is counting on the contribution of local knowledge to enrich the dataset both with new business entries and pictures. The collaboration between archival research and community involvement can breathe new life into the history of Greek businesses, through the lens of GIS mapping.

***

The Greek Businesses in Toronto Mapping Project was completed by Alexandros Balasis, a PhD candidate in History at York University. The research was supported by a Partnership Development Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada titled Greeks in Canada; a Digital Public History Project (890-2021-0087; Principal Investigator Sakis Gekas).

March 16, 2025

Notes

[1] Hercules Papamanolis, Περιληπτική Ιστορία του Καναδά και Ελληνο-Καναδικός Οδηγός [Concise History of Canada and Greek Canadian Guide] (Montreal: Canadian Greek Publishing Ltd., 1922), p 109.

[2] Konstantinos Diogos, “Ingenious Emigrants,” inDemon Entrepreneurs: Refashioning the “Greek Genius” in Modern Times, eds. Ioannis Stefanidis, and Basil Gounaris, 139–54 (London: Routledge, 2023).

[3] Andrew W. Beveridge, “Immigration, Ethnicity, and Race in Metropolitan New York, 1900–2000,” in Past Time, Past Place: GIS for History, ed. Anne Kelly Knowles (Redlands, CA: ESRI Press, 2002), 67–77.

[4] Kourelis, Kostis, and David Pettegrew. “The Greek Communities of Harrisburg and Lancaster: A Study of Immigration, Residence, and Mobility in the City Beautiful Era.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 87, no. 1 (2020): 66–91.

[5] Greek Shopping Map: https://mcgillmoderngreek.github.io/mcgillmoderngreek/; Greek households with a telephone landline (1950-1975): https://gadolou.github.io/greeks/; Map of Greek informants of Immigrec with places of origin and arrival: https://virtual.immigrec.com/rooms/immigrec-map/index.html?&l=en&1584993794.

[6] The “City Builders” examines through oral histories, interactive maps, and timelines, the challenges immigrant workers faced, including labour conditions, union efforts, and the influence of organized crime: https://toronto-city-builders.org/; DH Italian-Canadian Foodways: https://italiancanadianfoodways-utoronto.hub.arcgis.com/.

[7] Papamanolis, Περιληπτική Ιστορία του Καναδά και Ελληνο-Καναδικός Οδηγός.

[8] First Annual Year Book of the Greek Community of Toronto and Ontario (Toronto: sn, 1930); George Vlassis (ed.), Hellenic Year Book Coronation Issue (Toronto: The Hellenic Church of St. George and Federated Greek Charitable Societies of Ontario, 1937).

[9] George Demetrios Vlassis, The Greeks in Canada (Ottawa: sn, 1942, p. 98–100); George Vlassis. The Greeks in Canada, 2nd ed (Ottawa: sn, 1953), p. 241–45.

[10] The Toronto Daily Star, 3 August 1918, p. 10; The Evening Telegram, 3 August 1918, p. 20.

[11] Ελληνικόν Βήμα, 14 November 1958.

[12] Eλληνική Εστία 1, June 1966; Ελληνική Εστία 4, 7, December 1969.

[13] Νέοι Καιροί, 25 March, 1967; Νέος Κόσμος, 11 August 1967.

[14] The directory is available and text searchable online through the Internet Archive website: https://archive.org/search?query=subject%3A%22Toronto+%28Ont.%29+--+Directories%22.

[15] Alexandros Kitroeff, «Υπερατλαντική μετανάστευση» [Transatlantic Migration], in Ιστορία της Ελλάδας του 20ου αιώνα [History of Greece of the 20th century], ed. Christos Hatziiosif, vol. A1 (Athens: Bibliorama, 1999), 129.

[16] George Vlassis, The Greeks in Canada (Ottawa: sn, 1953), 92.

[17] Peter Chimbos, The Canadian Odyssey: The Greek Experience in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewar, 1980), 25–26.

[18] James Woodsworth, Strangers within Our Gates, or, Coming Canadians (Toronto: F.C. Stephenson, 1909), 167.

[19] This category includes restaurants, cafés, tea rooms, grills, and confectioneries.

[20] “Peonage is alleged,” The Globe, 20 August 1909, p. 12.

[21] This catefory includes flower shops, clothing stores, jewellery stores, furniture shops, tobacco shops, and grocery stores.

[22] This category includes shoeshine parlours, tailors, dry cleaning, barber shops, hairdressers and photographers.

[23] Vlassis, 186–87.

[24] For more: Florence Macdonald, For Greece a Tear: The Story of the Greek War Relief Fund of Canada (Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1954).

[25] “Red Cross is aided by grateful Greeks,” Toronto Daily Star, 16 May 1942, 2; “All Greek stores helping Red Cross,” Toronto Daily Star, 18 May 1942, 13.

[26] Απόδημοι Έλληνες [Greeks Abroad] (Αθήνα: Εθνικόν Κέντρον Κοινωνικών Ερευνών, 1972), 14.

[27] Alexandros Kitroeff, «Η Μεταπολεμική Μετανάστευση» [Postwar Migration], in Οι Έλληνες στη διασπορά: 15ος-21ος αιώνας [Greeks in the Diaspora: 15th-21st Century], eds. Ioannis K. Hasiotis, Olga Katsiardi-Hering, and Eurydice Ampatzi (Athens: Hellenic Parliament, 2006), 76.

[28] This is a rough estimation based on the number of business I recorded by decade and the distribution of Greek population in Canada by province as provided by Peter Chimbos in The Canadian Odyssey: The Greek Experience in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1980), 30–31.

[29] Roger Waldinger and Howard Aldrich, “Trends in Ethnic Businesses in the United States,” in Ethnic Entrepreneurs: Immigrant Business in Industrial Societies, eds. Waldinger Roger David, Howard Aldrich, and Robin Ward (Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 2006), 41–42.

[30] The names included street names (e.g., Dupont Coffee Shop, Danforth Sweets, Harbord Lunch) or anglicized versions of the proprietors’ names (e.g., Letros Restaurant, Bassel’s, Steele’s Restaurant), with more “Greek” names like Plaka, Olympia, and Zorbas emerging in the 1960s.