The Bicentenary of the Greek Revolution as Diplomacy: Philhellenism and the Question of Liberty in Greek/America

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

What would liberty mean, and for whom,

in a continental empire?

—Jeffrey Ostler

… we can mark Greece’s Bicentennial here in the U.S. by using our immigrant experience and Hellenic values to not only battle “hate,” but the bias and xenophobia that leads to this hate.

—Endy Zemenides,

Executive Director of the Hellenic American Leadership Council

Since the Carter administration (1977–1981) issued the Presidential Proclamation commemorating Greek Independence Day on March 25th—a date officially designated as the call for arms against the Ottoman empire in 1821—this anniversary has turned into an annual ritual of diplomacy. Greek American politicians and public figures, along with the U.S. and Greek government officials, utilize the ceremony to affirm and strengthen the bonds linking the two countries. The making of bilateral mutuality builds on an array of historical affinities: the foundational importance of the classical Greek past for early American republican thought; the support of the U.S. civil society toward the Greek revolution; the abolitionist and suffragist activism of U.S. Greeks in the nineteenth century; the advocacy of the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA) in 1922, for the inclusion of Americanized immigrants in the polity; and the 1965 march of Archbishop Iakovos on the side of Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Alabama, in support of the Civil Rights Movement.[1] Diplomacy animates a politics of mutuality along a Greek/American tripartite axis—the United States, Greek America, and Greece—around the ideology of liberty as the foundation for self-government and civic equality.

Greek/American diplomacy grants all three political actors—the two nations and the diaspora—with historical agency in the pursuit of freedom in a series of mutually beneficial actions but centers its interests in philhellenism—the American people’s mobilization on behalf of the Greek national cause. Indeed, if the “commitment to the political and religious freedom” was what “made the Greek Revolution important” to Americans, diplomacy elevates philhellenism and liberty as its organizing principle in contemporary commemorations of Greece’s independence.

Given this institutionalized discourse, it was only to be expected that diplomacy would magnify the theme of liberty during the 2021 Bicentenary of the Greek Revolution. At the highest level of government, President Biden’s Proclamation “A National Day of Celebration of Greek and American Democracy, 2021” tellingly captures this diplomatic angle:

Exactly 200 years ago, inspired by the same ideals of liberty, self-governance, and passionate belief in democracy that sparked the American Revolution, the people of Greece declared their independence. Today, the people of the United States join the Greek people … celebrating two centuries of enduring friendship between our nations.

On Greek Independence Day, we celebrate the history and values that unite the United States of America and the Hellenic Republic. … Philhellenes championed Greece’s quest for independence, forging a close connection between our peoples that has flourished over the ensuing years.

The organization of Greek/American bicentenary commemorations involved collaborations among various state and local governments, Greek American organizations, and the Greek government. In the most iconic mode of commemoration, grand public spectacles in U.S. cities enhanced the bicentenary’s public visibility by illuminating landmark buildings, bridges, and landscapes with the colors of Greece. In Los Angeles, for example, the American Hellenic Council of California and the local Greek American community were instrumental in the decision by the city government to light the City Hall and the Santa Monica Pier Ferris Wheel in blue and white in honor of the commemoration.

Honorary events stressed a repertoire of repeatedly evoked themes such as the debt the world owns to classical Greece, the contributions of Greek Americans to their home society, and the mobilization of American philhellenism in support of the Greek revolution. Diplomacy turned American national spaces into hyper-visible Greek/American ones.

The value of the bicentenary as a venue for diplomacy offers insights on the role of the diaspora to mediate bilateral relations between its home and historical homeland. Given this function, it is important to identify the diaspora’s modes of participation in the bicentenary’s politics of mutuality and specifically explore how it utilized the political value of liberty and the movement of philhellenism for its purposes. A preliminary survey of the vast Greek American involvement in the honoring of the bicentenary points to the spectacle, the monument, and the celebratory performative narrative as the prevailing venues for building mutuality.[2] Diaspora diplomacy employed images, words, special effects, monuments, and landscapes to valorize liberty and philhellenism.

It is significant to note that in its foregrounding of liberty and philhellenism, the bicentenary sidestepped their historical complexities, as often is the case with celebratory commemorations. This simplified idealization drives this writing. Is simplification and idealization the only option to honor a major occasion, even such as the bicentenary? Or, is there a space in this celebratory narrative to critically nuance liberty and philhellenism in a manner that simultaneously historicizes them and serves the goals of diplomacy?

In this blog, I would like to probe the question of the political and policy implications of idealizing liberty and propose that public scholarship can productively nuance the narrative of liberty by acknowledging its contradictions in the practice of this ideal without compromising the honorary tenor of the commemoration. In fact, I suggest that critical reflection expands the scope of Greek/American diplomacy to include various historically oppressed groups in the United States, such as Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Chican@s. The task on hand is to design strategies and develop the rhetoric to recognize historical truths in a manner that expands the purposes of Greek/American multilateral diplomacy and advances it productively.

Diplomacy in Spectacle, Performance, and Monuments

The Sail to Freedom is a significant bicentenary event spectacularizing liberty. Organized in New York City under the auspices of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the General Secretariat of Greeks Abroad and Public Diplomacy, it brought together members of the Greek parliament, American and Greek American government officials, philhellenes, as well as diaspora civic and religious figures, including business people, professionals, and philanthropists. The introductory speeches underlined the long-lasting linkages between the two countries around the mutual love of liberty. They utilized the occasion to express interest in furthering bilateral relations, including future economic and geostrategic cooperation.

The speech by U.S. Representative Carolyn Maloney—a politician exalted for her philhellenism and whose district includes areas of a high density of Greek American residents—echoes the diplomatic language organizing the commemoration narrative:

If you love freedom, you have to love Greece, because the initial ideas and the philosophy and the [democratic] form of government came from Greece. So if you love freedom, you have to honor and love Greece. And it was Greece that inspired the American Revolution. It was the ideals from Greece that told us what to do, what we should strive for, and when Greece fought for their independence, it was American presidents Jefferson, Madison, who strongly supported Greece and encouraged Americans to go over and fight and be part of that effort, some died, but many who went to Greece came back and became the leaders of the Abolitionist Movement and the Suffrage Movement for more ideals here in America, so we all owe so much to Greece. I’m very honored to represent the largest and most dynamic community in America, we call it Little Athens in Astoria, Queens, and on the feast days, you can close your eyes and think you’re almost in Greece.

The ensuing spectacle involved a flotilla of ships in a phantasmagoric procession toward the Statue of Liberty, selected as a destination for its symbolic value of universal freedom. With the annual parade commonly commemorating Greek Independence Day on New York City’s Fifth Avenue canceled because of COVID-19, the Hudson River offered the setting for the making of a new Greek/American transnational space. The sea-centered spectacle meant to communicate “the vital contribution of Greek mariners to the success of the Revolution and the deep relation of the Greek people with the sea that goes back to antiquity” at a particular geographic point—Ellis Island—“that unites Europe with America.”

The rituals of mutuality in the event included Greek American soprano Sofia Diana Antonakos singing the American and Greek national anthems from the headship facing the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor and the Greek and U.S. flags being raised in the masts. Two historical Greek/American interconnections add historical significance to the Greek/Americanization of this national space: (a) the U.S. Government briefly relaxing its official neutrality “that led to the addition of an American-built warship, the Hope— renamed Hellas—being added to the Greek Revolutionary Navy (Hatzidimitriou 2015, 6); and (b) the AHEPA contributing significant funds between 1986 to 1991 toward the restoration of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, New York, for which the organization received special recognition in 2007 by the Department of the Interior. Contemporary politics of mutuality are built on layers of the politics of mutuality in the past.

American philhellenism, a nineteenth-century discourse positing ancient Greece as the political and cultural exemplar of western civilization and in turn fueling U.S. material and humanitarian aid to the Greek revolution, was featured centrally in bicentenary public diplomacy. It was cast as the embodiment of love for liberty, interconnecting the American with the Greek revolutions, ancient Greek democracy with U.S. constitutional thought, and U.S. philhellenism with modern Greeks and the “rebirth” of Hellas in their liberated soil. As a rhetorical trope, the ideology of love for liberty linked the Greek and the American past and present, pervading formal proclamations, library exhibits, documentaries, public spectacles, academic webinars, and theatrical reenactments. The ideology of liberty saturated the bicentenary’s official and public diplomacy.

The American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA) featured American philhellenism centrally, as expected, given the organization’s historical deployment of philhellenism for the purposes of public diplomacy. As early as 1939, the Sons of Pericles—AHEPA’s male junior auxiliary—dedicated a monument honoring the memory of the fallen U.S. philhellenes in the battlefield of Missolonghi, a commemorative action which the joint Resolution in Congress rendered as one “cementing and binding the good will that exists between the two countries of America and Greece.” This monument marks the beginning of AHEPA’s “instrumentalization” of U.S. philhellenism for diplomacy, an entanglement that endures to this day (Kitroeff 2021).

In the bicentenary, AHEPA foregrounded its appreciation for the American people’s solidarity with the Greek revolutionaries in a theatrical re-enactment honoring New York City’s American Greek Committee, one of the leading philhellenic organizations which were mobilized in U.S. cities to collect humanitarian aid for Greece. References to liberty permeated the performative reconstruction of the Committee’s staging of its 1827 Greek Ball—the year when the fundraising was particularly substantial. The spectacle included a panel with the Greek motto “Liberty or Death,” a war cry in the Greek Revolution, which the AHEPA host juxtaposed with “Give me liberty, or give me death!”, a statement attributed to Patrick Henry for a resolution to dispatch Virginian troops for the American Revolutionary War. Greek/American mutuality—a consistent ideology running throughout AHEPA’s history—also centered on this event.

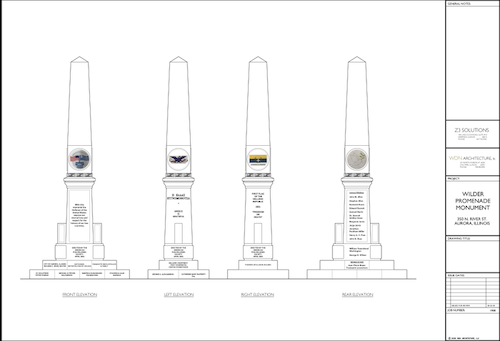

Philhellenism supplied a major trope for bicentenary-driven diplomacy to yet another organization during the bicentenary, the American Philhellenes Society (APS). It involved the dedication of the American Philhellenes Monument in Aurora, Illinois, in the presence of Greek American and American dignitaries. The event was greeted by U.S. Senator Richard J. Durbin and the president of the “Greece 2021” Committee Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, who cast the inaugurated monument as a reflection of “the friendly relations of the two peoples,” to which APS “contributes to maintaining” (The National Herald Staff, 2021, 5). Here too, the diaspora is positioned as a mediating agency in regional and international diplomacy.

Greek/America—Black/America: Expanding the Politics of Mutuality

The practice of bicentenary diplomacy included Black Americans. A precursor of this expansion is the late Senator Paul Sarbanes’ official commemoration of the 192nd Anniversary of Greek Independence Day in 2013. This year coincided with several landmark events in African American history. Sarbanes, who was a key figure in forging ties between the Greek American and the African American communities in his home state of Maryland, introduced this Congregational resolution, under the title “America and Greece, Strength and Solidarity”:

In this year, when we also celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, and the 100th anniversary of both Harriet Tubman’s death and Rosa Parks’ birth, it is especially fitting to recall how Hellenes and African Americans have reached out to one another to provide mutual support. When Hellenes acted to liberate themselves in 1821, James Williams, an African American sailor from my hometown of Baltimore, joined the Greek revolutionary navy and fought at the Battle of Navarino. In turn, John Zachos and Photius Fisk, orphans of the Greek War of Independence, became passionate abolitionists in America. Zachos was a member of the Educational Commission of Boston and New York. Fisk, a U.S. Navy chaplain, helped slaves find freedom by supporting the Underground Railroad.[3]

The acknowledgment of this interethnic mutuality intensified during the bicentenary. Greek American organizations such as The Eastern Mediterranean Business Cultural Alliance (EMBCA), the Hellenic American Leadership Council (HALC), the National Hellenic Museum (NHM), and AHEPA honored the Black philhellenes who joined the Greek War of Independence as well as nineteenth-century U.S. Greek abolitionists. The events, mainly in the form of webinars, foregrounded the catalytic role of the rhetoric and tactics of the philhellenes in inspiring and empowering the abolitionist movement.

This narrative promoted public dialogue between the Greek American and the African American communities. EMBCA, for example, organized a series of public conversations which brought together Greek American researchers and organizations such as the AHEPA with African American historians and associations such as the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce. Synergies between academic programs and the Greek government fostered an appreciation of Greek/American advocacy of abolitionism. The webinar “From Orphan to Abolitionist: Photius Fisk and the Making of Greek America,” for example, was co-sponsored by the U.S. Greek, U.S. Embassy, and the UCLA Stavros Niarchos Foundation Center for the Study of Hellenic Culture in honor of the 2021 Black History Month. The most recent expression of this narrative is the short video “Hellenism and the Civil Rights Movement,” a product of cooperation between the Embassy of Greece in Washington and the Hellenic American Leadership Council (February 14, 2022).[4] Greek/American bicentenary diplomacy expanded its scope to include Black people in the audiences it seeks to reach while incorporating academics in the conversation.

Historicizing Liberty: Public Scholarship and Multilateral Diplomacy

In its aim to build bonds across differences, diplomacy commonly relies on key concepts with broad cultural currency to subsequently circulate highly recognizable and readily reproducible ideas and ideals whose credibility is anchored in actual historical events. But, not unlike national identity branding, diplomacy’s rhetoric strips concepts and cultural movements from their historical complexity (Anagnostou 2022a).

The bicentenary’s evocation of liberty essentially performed this ideological operation. Policy statements, popular narratives, and some scholarship addressing non-academic audiences refrained from probing the ideology and applications of nineteenth-century U.S. liberty critically. Liberty at the time was a notoriously exclusionary ideal, being connected with the denial of freedom to “non-White” people within the Republic, and also, significantly, linked with the project of cultural and religious colonization of a “free” Greece. This is to say that the prevailing bicentenary narrative neglected to acknowledge the embeddedness of philhellenic discourse in structures of racial oppression and religious hierarchies. This key omission represents an obvious move to avoid compromising the celebratory branding of the commemoration. But this solution largely bypassed the opportunity to articulate an alternative mode of diplomacy sensitive to the historical experiences of groups which ethnocentric liberty oppressed—and continues to oppress—such as Native Americans, Chican@s, and Asian Americans. Yet, cited in the epigraph, the position of the Hellenic American Leadership Council (HALC) makes a point to link the bicentenary with the necessity for Greek American activism to safeguard the civil liberties of groups such as Asian Americans who are openly targeted in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic.

“Liberty” requires historization. As Jeffrey Ostler’s phrase in the epigraph indicates, this political ideal calls for reflection about its meanings, assumptions, and applications within power structures, determining who qualified to possess it in the long nineteenth century. While the bicentenary stressed the influence of philhellenism and its rhetoric in the abolitionist and women’s rights causes, the ways in which philhellenes failed to apply liberty in relation to “non-White” groups was marginalized, if not sometimes silenced. For, not all northern philhellenes were abolitionists and some of those who were often ended up advocating positions favoring slaveholders. Philhellenic southerner slaveholders, on the other hand, defined liberty as their categorical right to slave ownership as they saw “no contradiction in opposing Greek slavery abroad and supporting African American slavery at home.” Their racial Hellenism framed the Greeks as the “victims of nonwhite oppressors,” worthy of the support of Whites (Santelli 2020, 8). In yet another terrain of racialized applications of liberty, some philhellenes did participate in the colonial dispossession of lands from Native American peoples, benefitting materially from the transactions. Sectors of the philhellenic movement then were motivated to grant liberty based on White intra-racial solidarity, not a commitment to its universal value. Placed in this context, bicentenary diplomacy confronted a fundamental contradiction regarding U.S. liberty, an ideal that advocated freedom for Greece but produced unfreedom for peoples such as Native Americans, Chicanos, and Asian Americans. The recognition of the plight of African Americans was a significant but not a sufficient step toward a more expansive bilateral policy sensitive to liberty’s negative political impact on other people.

The discourse of liberty was deeply embedded with racist policies in the era of empire-making—the nation’s Western expansion (1803–1890). The question of who qualified to possess it was informed by exclusionary laws and implemented with fierce practices violating the self-determination of the colonized Native Americans, dominating and depriving Mexicans of cultural autonomy, and demonizing Asian immigrants, whom it eventually subjected to exclusionary immigration policies. Liberty was deployed to advancing the interests of whiteness, the hierarchical system which cast White people as a superior race, destined to dominate over inferior races, seen as racially unworthy of self-determination. In fact, the guiding ideology linking empire and freedom posited the “essential condition for liberty” as “widespread land ownership for white men” (Ostler 2004, 200).

Within the Americas, the contrast in the political thinking between two public figures both endorsing liberty, Daniel Webster (1782–1852)—a noted American philhellene, known for his “internationally famous speech in favor of the Greek revolutionaries” in 1824—and Simón Bolívar (1783–1830)—a Venezuelan military and political leader known as the Liberator in South and Central America—about the place of colonized and enslaved people in a Republic is telling. Bolívar sought to create a “broadly based social equality, built on laws and institutions that could mediate between the strongly discriminated racial groups that characterized postcolonial society” (Gustafson 2006, 410). He was preoccupied with racial hierarchies and sought re-distribution of land and wealth to address the problem. Webster’s politics, on the other hand, was racially biased in his understanding of liberty, justifying the removal of Native peoples from their ancestral territories. Native Americans served “principally as a foil, representing for him the condition of peoples” who, lacking “the institutions of modern liberty,” have been “consequently displaced” (410). Though an early abolitionist, Webster compromised his opposition to slavery when fearing civil war; he supported the return of escaped slaves to their owners for the sake of preserving the Union.

In the context of the Greek Revolution, the civilizational and religious hierarchies associated with philhellenism embedded liberty into America’s redemptive civilizing mission on a global scale. The redemption of the Greeks “assumed a ‘secularized missionary spirit’ which endeavored to spread an American understanding of freedom and liberty to all parts of the world” (Santelli 2020, 117). It entailed Greece’s “intellectual colonization,” and was shared by philhellenes who connected Greek independence with secular and religious reformation—“elevating” and “uplifting”—the modern Greeks into American likeness. “Philhellenism—being . . . an orientalism in the most profound sense—,” Stathis Gourgouris (1996) argues, “engages in the like activity of representing the other culture, which in effect means replacing the other culture with those self-generated, projected images of otherness that Western culture needs to see itself in: the mirrors of itself” (140, author’s emphasis).

Similarly, for American missionaries, a liberated Greece “opened up a historic opportunity … to recruit and educate religious followers” in a nominally Christian country whose religious practices they disdained and desired to transform (Van Steen 2022). Notably, Western philhellenism’s support for Greek liberty did not translate into recognizing Greece’s liberty for self-determination. As anthropologist Michael Herzfeld notes, upon independence, the “Greeks were forced to fit their national culture to the antiquarian desires of Western powers.” If Western powers at the time deployed philhellenism as an instrument to advance their imperial aspirations, U.S. philhellenism was far from a disinterested movement, being implicated with aspirations for political, cultural, and religious hegemony. As an ideologically heterogeneous movement, U.S. philhellenism requires historicization—indeed, examination “from the perspective of different kinds of” writers, from different regions, “and different walks of life” (Calotychos 2003, 238)—with an eye to identify those receptions of Hellenism which articulated anti-colonialist and anti-racist politics within as well as outside the United States.[5]

In Lieu of Conclusion

The U.S. liberty narrative during the Greek Revolution was racialized, engendering White superiority and its attendant racial hierarchies and internal rankings within Christianity. It granted the right to liberty selectively and conditionally, advocating it for some groups and rejecting it for others. It privileged Greek liberty for the cultural and racial affinities that American philhellenes felt for ancient Greece and, by extension, the modern Greeks who were viewed as the Christian, White “heirs of an ancient political tradition of liberty and self-government” (Santelli 2020, 3). Instead of unqualified celebration, therefore, this exclusionary intra-racial application of liberty calls for reflection about its political and policy implications today.

Why incorporate this critical element in the diaspora’s bicentenary narrative? Because the bicentenary anniversary is not merely an ethnic affair and an occasion simply for bilateral policy, but an event with broader civic implications for all groups within a polity. The popular bicentenary narrative in the event Sail to Freedom recognizes this broader scope, albeit fleetingly and in the most abstract level when it marks the Statue of Liberty not merely part of Greek/America but also universal liberty. And as I have noted, the Hellenic American Leadership Council acknowledges the need for Greek America to reach toward broader inter-racial solidarities and alliances.

The political, cross-ethnic dimensions of the bicentenary anniversary did not escape some scholars who emphasized the need for recontextualizing the scope of the commemoration. In the United States, for example, the diaspora’s celebration in a particular site is linked with an influential philhellene implicated in the colonial dispossession of land from Native Americans; and in Australia, the call was made to connect the bicentenary narrative with the respectful recognition of the oppression of Indigenous peoples.

The relevance of these interventionist insights lies in their calling for a research paradigm that places the various Greek diasporas in relation to the histories and cultures of other ethnic and racial groups in their new homes, a call which is of value for imagining a broader multilateral Greek/American diplomacy.

Two questions with policy implications were raised in these critical interventions: What does it mean to celebrate an event—the Bicentenary—in which the right to liberty was granted to a particular people while simultaneously stripped away from others? And, what is the contemporary responsibility of those who were privileged to those who were devalued? (see Anagnostou 2022b). Though published early in 2021 and on widely accessible websites, this invitation (and vision) to expand the bicentenary’s scope remained largely unheeded by those who staged the anniversary for public consumption. Policy and public scholarship made a positive move in incorporating African Americans in the anniversary, as I have indicated, but fell short of further advancing a genuinely multilateral policy strategy.

The interest in liberty and philhellenism continues unabated, involving various initiatives by sectors of the Greek/American civil society—including collaborations between the academy and cultural organizations—which enjoy the support of the Greek government.[6] Diaspora organizations, scholars, and policymakers are bound to grapple with the ethics and politics of the issues I outlined above in the not-too-distant future.

On the one hand, this is because public scholarship will be increasingly facing this civic and political responsibility as collaborative webinars between academics and cultural organizations are becoming a popular venue for interfacing with the public.

On the other hand, diplomacy will be engaging with denser demographic networks in multi-ethnic democracies, which makes the fostering of multilateral relations of mutual respect necessary.

In this ever-shifting landscape, reflective public scholarship could contribute to policy in at least two ways: (a) by bringing awareness to diaspora institutions about the civic and moral implications of their self-representations of history and culture; and (b) raising new research questions to advance transcultural and inter-ethnic understanding. The work ahead involves the task of effectively translating complex historical realities to governmental and non-state audiences and the political will of incorporating reflection as an integral component of policy and community cultural practices.

Yiorgos Anagnostou

teaches at The Ohio State University.

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “Diaspora Public Diplomacy at a Time of Homeland Crisis: The Philotimo Nation as Global Distinction.” In Diaspora Engagement in the Shadow of the Greek Economic Crisis and Beyond, edited by Othon Anastasakis, Antonis Kamaras, Foteini Kalantzi, and Manolis Pratsinakis. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022a (In print).

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “Recontextualizing the Bicentenary in Greek America and Greek Australia: Greek Civic Identities in the Diaspora.” In The Greek Revolution and the Greek Diaspora in North America, edited by Maria Kaliambou. Hellenic Open University Press, 2022b (forthcoming in Greek).

Calotychos, Vangelis. Modern Greece: A Cultural Poetics. New York, NY: Berg, 2003.

Gourgouris, Stathis. Dream Nation: Enlightenment, Colonization and the Institution of Modern Greece. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996.

Gustafson, Sandra M. “Daniel Webster and the Making of Modern Liberty in the Atlantic World.” American Antiquarian Society, 116.2 (2006): 395–412.

Hatzidimitriou, Constantine G. “Revisiting the Documentation for American Philanthropic Contributions to Greece’s War of Liberation of 1821.” Journal of Modern Hellenism 31 (2015): 1–22.

Kolocotroni, Vassiliki and Eleni Papargyriou. “2021: Spectres of Commemorations Past.” Journal of Greek Media and Culture 7.2 (2021): 143–52.

National Herald Staff, The. “American Philhellenes Monument Dedicated in Wilder Park, Aurora, IL.” The National Herald, 2-8 (October 2021): 5.

Ostler, Jeffrey. “Empire and Liberty: Contradictions and Conflicts in Nineteenth-Century Western Political History.” In A Companion to the American West, edited by William Deverell, 200–18. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Santelli, Maureen Connors. The Greek Fire: American-Ottoman Relations and Democratic Fervor in the Age of Revolutions. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020.

Van Steen, Gonda. “The United States as a Haven for Greek Revolutionary War Orphans? Myth and Reality.” In New Perspectives on the Greek War of Independence 200 Years On: Myths, Realities, Legacies and Reflections , edited by Yianni Cartledge and Andrekos Varnava. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022. (Forthcoming).

Zeniou, Simos. “Dividuous Waves of Greece:” Hellenism between Empire and Revolution.” Politics. Rivista di Studi Politici 5.1 (2016): 71–88.

Notes

[1] See the 2013 Congregational resolution, “America and Greece, Strength and Solidarity” by the late Senator Paul Sarbanes.

[2] For a theoretical exploration of spectacles and monuments in commemorations of the Greek Revolution in Greece, see the special issue in the Journal of Greek Media and Culture, edited by Vassiliki Kolocotroni and Eleni Papargyriou (2021).

[3] A benefit event in support of the Greek cause was also organized in 1827 by African Americans, who were positioned to understand “the desire a group of people could have for freedom” (Santelli 2020, 108).

[4] In this context, the Greek News Agenda—an online English language platform issued by the Secretariat General for Public Diplomacy—sponsored the essay “Greek Americans and the Civil Rights Movement.”

[5] For an example in relation to British philhellenism, see Simos Zeniou’s (2016) revisionist reading of P.B. Shelley’s famous lyrical drama “Hellas.”

[6] See, for example, the Cultural Tribute to Liberty Festival, organized by the American-Hellenic Chamber of Commerce (March 4-6, 2022), “a virtual showcase of culture productions, initiated by the AmCham Greece Culture Committee [and] supported by the generous participation of esteemed organizations, institutions, and artists (announcement by the Embassy of Greece in Washington, D.C. / Public Diplomacy Office. March 2, 2022). Also of note is an academic collaboration with the Society of Hellenism and Philhellenism in the sponsoring of an “Early Career Fellowship in Philhellenism” (2022–2023).