Greek America in the Images of America Series

By Kostis Kourelis

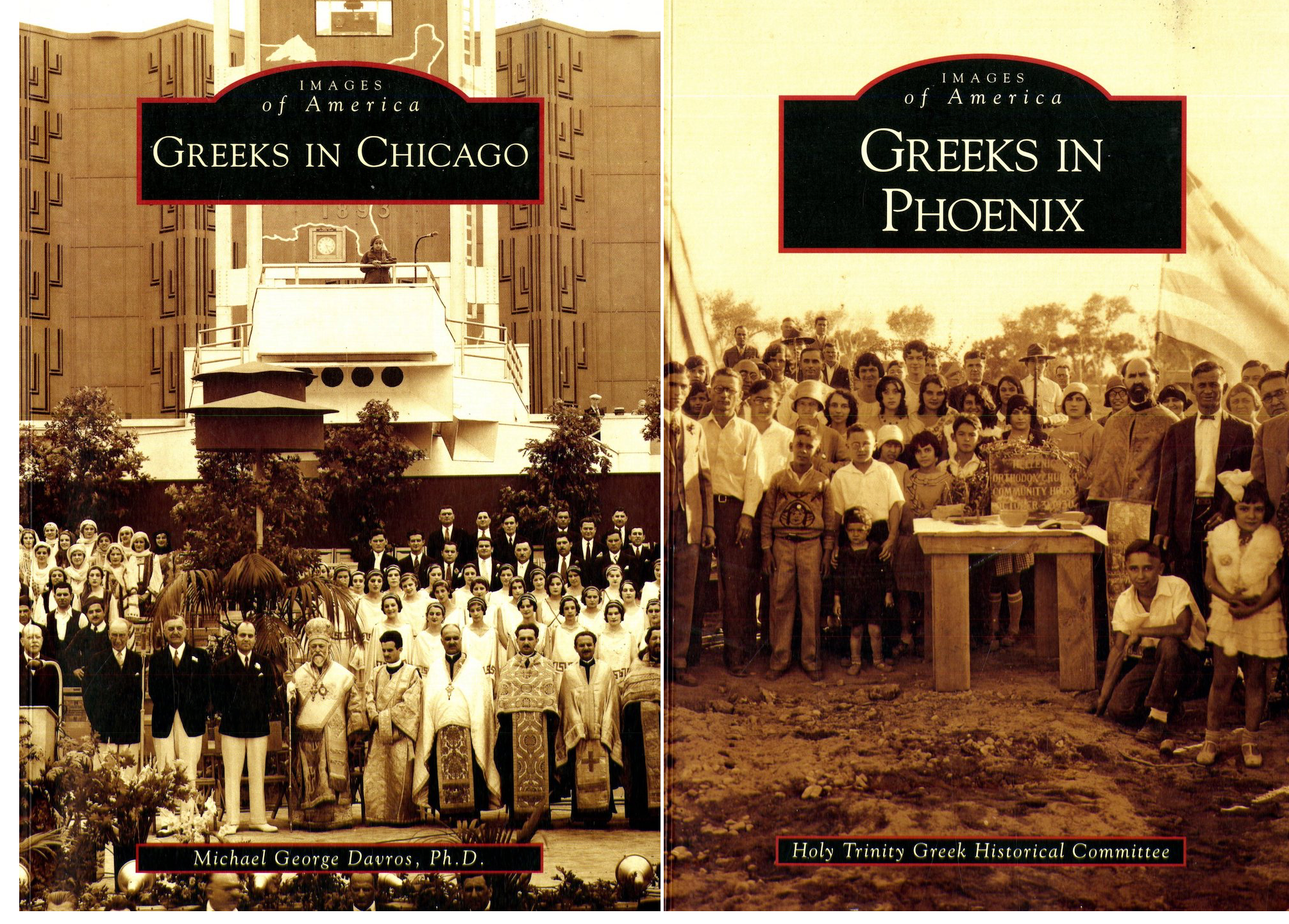

Holy Trinity Greek Historical Committee, Greeks in Phoenix (Images of America). Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. 2008. Pp. 128. 200 b/w illustrations. Paper $19.99.

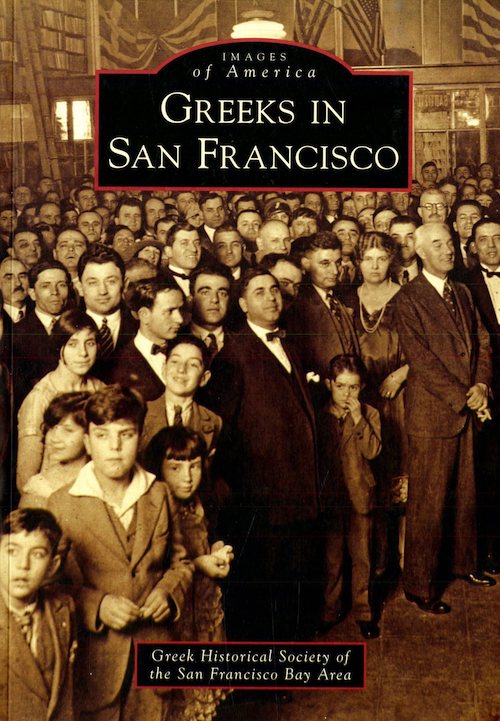

Greek Historical Society of San Francisco Bay Area. 2016. The Greeks in San Francisco (Images of America), Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. Pp. 128. 212 b/w illustrations. Paper $21.99.

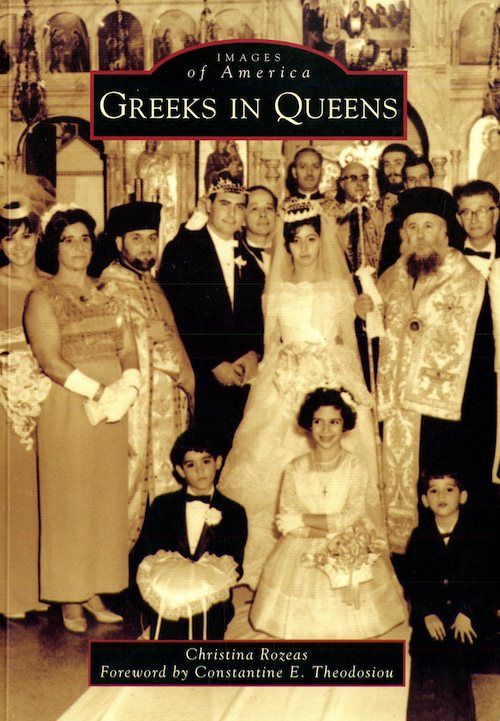

Rozea, Christina. 2012. Greeks in Queens (Images of America), Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. Pp. 128. 189 b/w illustrations. Paper $21.99.

Davros, Michael George. 2009. Greeks in Chicago (Images of America), Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. Pp. 128. 226 b/w illustrations. Paper $21.99.

Bucuvalas, Tina. 2016. Greeks in Tarpon Springs (Images of America), Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. Pp. 128. 200 b/w illustrations. Paper $21.99.

A studio portrait, a church facade, a crowded picnic, a luncheonette interior, a wedding photo, and a Greek festival are all images that distill some essential memories from the Greek American experience. The imagined American melting pot of European migrants occurred before Kodak’s disseminated color photography, making the black-and-white photographs a vehicle for periodic nostalgia. Since 1993, this space of visual memory has been reactivated through the slender, sepia-color paperbacks of Arcadia Publishing. The Greek communities of Atlanta, Charleston, Chicago, Houston, Merrimack Valley, Phoenix, Queens, Stark County, San Francisco, Staten Island, and Tarpon Springs are among the 7,904 volumes published in Arcadia’s Images of America series. Five volumes spanning across the United States from east to west and north to south are reviewed here. Each volume represents a monumental accomplishment for the community of volunteers that produced it, while challenging unrepresented cities to undertake their own contribution. As image collections, the volumes trigger deep empathy with the heroic generations that preceded. Each volume urges us not to forget the toil upon which the solid foundations of Greek American communities were built.

Every Images of America volume has a standard black-and-white image format. A short introduction and captions under each illustration are the only texts. Beyond the factual information and implicit assumptions embedded in the captions, the Images of America books make no argument, propose no thesis, and produce no scholarly synthesis. Written by members of the local communities, the books impart a grass-roots sensibility and offer retrospective celebration. A trade rather than an academic press, Arcadia has devised a brilliant publishing model by producing regional and local histories distributed to local markets (bookstores, museums, and universities) at low cost.

Arcadia was founded in 1993 at the height of the American culture war between a Republican Party focused on conservative historical values and a Democratic Party that had inherited progressive values and a dialectical perspective of history (see review, Rice 2009). During the 1992 National Republican Convention, Pat Buchanan initiated an ideological critique of professional academia for privileging inquiries over class, race, and gender. Republican politicians called for a return to traditional American values of faith, family, and nation. Newt Gingrich called for shutting down the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment of the Humanities as bastions of anti-Americanism. Republican victories in the 1994 congressional and the 2001 presidential elections shifted the increasingly limited federal funding to research on traditional values and the assimilation of immigrants into the American dream through faith, resilience, and a work ethic. Decoupled from the context of larger historical forces, heritage was atomized to individual experiences with great commercial success. The 1990s witnessed the explosion of a memory industry that, some have argued, contributed to a historical amnesia (Huyssen 2000; Bauman 2000).

Arcadia Publishing is an episode of print-based nostalgia, a niched revival of the local combating digital globalization. In 2004, it became an independent press with its headquartered in Charleston, South Carolina, appropriately, the city that established the first historic preservation district in the United States. Sixteen years later, in 2018, Arcadia was bought by a larger acquisition company. Its stock currently includes 14,000 volumes in series such as Images of America,Campus History, Postcards of America,Images of Baseball, Images of Rail, Black America, and History of Aviation. The thirteen volumes devoted to Greek communities are significantly fewer in number than volumes devoted to Jewish (ninety-one), African-American (eighty-three), or Italian (sixty-two) communities but are statistically prominent considering that the Greek American population is 28, 12, and 5 times smaller than the populations of African Americans, Italian Americans, and Jewish Americans, respectively. This visibility of Greeks in the Arcadia series is important but also deceiving since its market is weighed regionally; for example, 3,360 volumes are devoted to New York City and 228 to Chicago alone. Collectively, the thirteen Greek volumes provide opportunities to make visual comparisons between regional communities.

Although ethnically diverse in its breadth, Images of America is formulaic. Each book is exactly 200 pages in length with a sepia-toned cover, 200-300 black-and-white images, and minimal text. In spite of its Greek name, Arcadia Publishing is devoted to the exploration of an idyllic American past, celebrating local contributions to the making of an imagined golden age that no longer exists. The mode of presentation is unabashedly nostalgic; it replicates dominant narratives and gives local communities a printed artifact to circulate, generating internal memories and promoting further scholarly work. To the general audience who may see a Greek volume next to others devoted to different communities from that region, the physical presence of the book (even if not actually purchased) offers a testimonial of recognition. Each volume’s real estate on the local bookshelf legitimates the actual real estate that the community once claimed next to other heritage-worthy minorities.

The five Arcadia books reviewed here illustrate the variety of expertise available in different communities. Tina Bucuvalas is the curator of arts and historical resources for the City of Tarpon Springs and was previously director of the Florida Folklife Program. She is a folklorists and curator of public programs and exhibitions with broad fieldwork in Latin America, the United States, and Greece. Bucuvalas was the subject of an interview in this journal (see Varajon 2017), and most recently she edited a landmark book on Greek American music (Bucuvalas 2019). Michael George Davros is professor of English at Northeastern Illinois University and credits late Andrew T. Kopan, professor at DePaul University, and Alice Orphanos Kopan for collecting the foundational archive for writing Chicago’s Greek American history. Christina Rozeas worked in the New York public school system, and the San Francisco book was compiled by a twelve-author team, the publication committee of the Greek Historical Society of the San Francisco Bay Area. Finally, the Phoenix volume was written by six authors representing the Holy Trinity Greek Historical Committee.

Arcadia’s mission statement is direct: “For over 20 years Arcadia Publishing has reconnected people to their community, their neighbors, and their past by offering a curbside view of hometown history and often forgotten aspects of American life” (Arcadia 2016). But what is Arcadia’s impact on Greek American history more specifically? What is its value beyond the cultivation of legitimacy and pride among the finite members of the community who will likely purchase the book? Most importantly, it fills an important gap in the relatively small production of local Greek American histories. It also provides evidence of a shared ethnic Greek American narrative that can be glimpsed from the organizational structure of all five books with common sections on the pioneering immigrants, churches, businesses, social organizations, and progress. Flipping through each volume, the reader gets the inevitable feeling of how interchangeable the experiences of Queens, San Francisco, Phoenix, Chicago, or Tarpon Springs may have been. But at second look, when the gaze moves beyond the black-robed priest in the foreground and discovers the trees or buildings in the background, the contextual differences of each community emerge. The equalizing 200-page format also reveals archival differences among the communities. It becomes clear that the volume on Queens, for example, is based on a smaller number of sources that resemble an extended family portrait. Additionally, the five volumes succeed in illustrating the architectural journeys of local Orthodox churches through photographs of spaces that have long disappeared, such as Chicago’s Holy Trinity established in 1897, the 1908 wooden Saint Nicholas of Tarpon Springs, or the Hellenic Orthodox Church Community House established in 1931 in Phoenix. The same can be said of the materialization of daily Greek labor through the depiction of places of work ranging from the sponge docks of Tarpon Springs, to shoe shine parlors in Phoenix, to the confectionaries of Chicago. In the few cases where both the address and date of a photograph is provided, the illustration contains the necessary metadata to evaluate the image’s content and to cross-reference it with other primary sources (maps, censuses, church records, oral histories, etc.).

While fulfilling the mainstream narratives of work, faith, perseverance, customs, and philanthropy, the pictorial histories also contain a few surprises such as the destruction of Phoenix’s church interior by two seven-year old boys in 1937. We see the typological similarities between the sponge warehouses and the 1908 wooden church of Tarpon Springs, the eroticization of the male Greek body in the popularity of Greek wrestlers, as well as the conflation of modernity and antiquity in Chicago’s Olympic Athletic Club, which had exclusive use of the Hull House gymnasium. We also learn of the mundane, such as the importance of the female candy dippers behind the confectionary storefront, or that Greek food shops had sawdust covering their floors for sanitation. We observe exceptional matriarchic families, where the male immigrant returned home and left his family to fend for itself, as well as the formation of Greek Republican clubs among a community that historically supported the Democratic Party. We even get a glimpse of Chicago Mayor Richard Daly playing with a komboloi, a striking image considering that his father was responsible for the destruction of Greektown there.

Curated to visually represent a story of good moral standing, the Images of America lack the photos that one might find in a more complete urban narrative—one that would allow for the inclusion of failure, temptation, and vice. Indeed, in his study of Greek American criminality, Thomas Gallant argues that diaspora history has rejected the lives and activities of individuals that “do not ‘fit’ the conventional stereotypes of Greek immigrants” (2009, 28). This would include members of the LGBTQ community, sex workers, pimps, padrones, gamblers, illegals, political radicals, and other highly visualized individuals who abound in photographic urban histories, such as Luc Sante’s (2003) portrait of New York, but would be removed from a church-based or family-values archive.

Although the Images of America series projects a universal image of ethnic individuals, the volumes cannot avoid celebrating foundational community members through their portrait. The reproduction of those biographical photographs communicates the individual’s stature. Thus, many of the photographs reproduced in the books are portraits that commemorate an individual. They do not belong to the art genres that celebrate anonymous characters amidst social life, following the Family of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (Steichen 1955). Instead, amateur and commercial photographers have biographical entanglements with their subjects. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes argues that beyond the socially translatable content ( studium) photographs contain a personal trauma (punctum) as the deceased stares back at you (Barthes 1981, 96). In the early photographs, that personage might be the first priest or the founder of the community. But in the later photographs, that personage is often the individual closest to the family of the collector or a community member that has achieved great economic or political status. Such exceptionality threatens to turn the visual story toward hagiography rather than representative objectivity. Although used in the Images of America volumes to represent a historical community, all the portraits originally served different purposes: to commemorate the deceased, advertise riches, facilitate matrimony, communicate to Greece, or even as legal evidence. In his critical study of photography, Allan Sekula argued that individual photographs cannot be separated from the system of informational exchange under which they were originally produced (1982). Sekula compared two of the best-known photographs of immigrants to make his point: Lewis Hine’s 1905 Immigrants Going down a Gangplank that was circulated in tracks to change public opinion and Alfred Stieglitz’s 1908 Steerage that was circulated in galleries and art magazines. Both documented the immigration realities of 1900s New York, but they were designed for radically different media of transmission. Hine’s photo was a vehicle for social reform, while Stieglitz’s photo was an autonomous work of aesthetic modernism. The medium of dissemination, argues Sekula, prescribes the visual content of photographic images that should not be interpreted outside of that context. Lacking information about the semiotic expectations that surround the creation of each original image, the viewer cannot engage with the Images of America beyond an impressionistic or sentimental first reading.

Arcadia Publishing encourages us to consider the role of photography in the Greek American experience more broadly. The limitation of the picture book genre opens conversations regarding the omission of other visions. Missing, for example, is the long tradition of photographic activism, where the Greek American subject is captured by the lens of social activists such as Jacob Riis and Hine whose work is not commemorative but instrumental to progressive reform. Paradoxically, the greatest body of Greek American photography may not be found in the United States but in Greece since many of the rural Greek photographers learned their trade as immigrants in American cities (Liontis 2013). The short archival picture books are not able to ask complicated questions about the role of photography as a creative or social expression within the Greek American community. When re-exhibitions of Constantine Manos’s Greek Portfolio were held in the Onassis Cultural Center in New York in 2007 and in the Benaki Museum in Athens in 2012 three decades after their original publication, two cultural institutions ushered an American into the official cadre of Greek photographers, but neither asked how Manos’s lens was shaped by a southern, sexually repressive community in Columbia, South Carolina. Here, one could argue that Manos’s Greek Portfolio (1972) is more American than Greek, while his American Color (1995) is more Greek than American. Even today, questions about the aesthetics of a Greek American photographic lens continue with America in a Trance by Niko Kallianiotis (2018). However, the archival nature of the Images of America series prohibits the inclusion of a reflective photographic practice, such as the one promoted by Anna Caraveli’s exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where photographs from village Olymbos in Karpathos were juxtaposed with images of the Olymbos diaspora in Baltimore taken by Manos and Liliane de Toledo (Caraveli 1985). Below the heritage patina, the Images of America volumes solicit questions of subjectivity but cannot answer them as collections without words. They offer opportunities for intertextual comparisons at a photo-by-photo basis with other film ethnographies of Greektowns in Baltimore (Moses 1981), Chicago (Moraites and Hagmann 1962), Oregon (Doulis 1977), Astoria (Marketou 1987), and Lowell (Sampas, Panas, and Nikitopoulos 1983).

Like many hyphenated European Americans, whose diaspora flourished in the industrial era, a significant sector of Greeks was to advance economically and reject the low-class immigrant status they left behind among the urban slums. The physical testament of the Greek diaspora has been erased by its own prosperity. The 1.3 million Americans who currently declare Greek ancestry have an average income that is 20% above the national mean. Economic prosperity has led to geographic mobility, and few Greek Americans live in the same physical environment of their early ancestors who arrived in the United States a century earlier. Moreover, along with other white ethnics, Greeks fled to the suburbs in the postwar period and severed any physical ties to the once-vibrant commercial urban centers that they served. In fact, when such individuals retain a space of remembrance and commemoration, it tends to be the Greek homeland, a return to the village with detours to the beach and archaeological sites. Thus, even though the Greek village is further away, it is visited more frequently than the inner cities where Greeks first landed. Greece’s persistence as a desirable tourist destination further reinforces repeated journeys between village and suburb that bypass the intermediary downtowns where Greeks originally labored. Although many Greek immigrants worked as proletariats in factories, mines, and heavy industry, the majority occupied an urban niche of service professions. Whether in a metropolis of millions or a town of hundreds, Greeks found a lucrative niche in four commercial sectors that served a thriving American urban middle class. The businesses listed in the early Greek American directories are almost exclusively confectionary, florist, shoeshine, and restaurant services. In contrast to professional niches by other immigrant groups (e.g., Jews in textile, Italians in construction, etc.), the Greek service industries depended on a daily self-presentation to the American consumer in the urban marketplace. The postindustrial collapse of American cities meant the collapse of its Greektowns. Take New York and Chicago, the two largest and best-known Greek cities; the first Greektowns in Lower Manhattan and Halstead Street, respectively, have been demolished by urban renewal in the 1960s.

In short, the Greek Americans of the twenty-first century find themselves without much physical evidence of their migration history. Greek Orthodox churches have served as civic markers, but their spiritual framework reinforces sacred time and cycles of commemoration. Few of the original churches of the Greek diaspora survive, leaving behind not only a dispersal of people, but also an erosion of archival management. Considering Greek America’s small size low demography compared to other ethnic groups, Greek Americans have been served by an extraordinary scholarly community. Below the national discourse of academic writing, there is another level of local scholarship that has not been fully realized. Greek Americans have spent much of their historical muscle to advertise the glories of classical antiquity and Byzantium. The shared mythic experience of Hellenism does not require the skills of documentation, curation, and preservation that are required for the writing of local histories. Between the parish level of mythical time and the scholarly level of evidentiary time, there remains a sizable gap for the preservation, curation, and interpretation of local experiences. This gap has been met by a number of community-based initiatives in oral history and museum collections (see listing of museums and oral history in The Modern Greek Studies Association’s Resources Archive, 2019). Images of America elevates the visibility and pride of local communities and challenges us to invest in interpretation of the vast amount of visual records scattered among Greek-American family and parish collections.

Kostis Kourelis is an architectural historian who specializes in the archaeology of the Mediterranean from the medieval to the modern periods. He also investigates how Byzantine art and architecture shaped modernist notions of identity, space, and aesthetics. His recent fieldwork has focused on the archaeology of the contemporary world, labor, housing, and immigration. In Greece, he directs archaeological surveys of deserted villages and refugee camps; in the United States, he directs projects on Philadelphia’s Greektown, North Dakota’s man camps, and Japanese internment camps. He is Associate Professor of Art History at Franklin & Marshall College. Publications include Houses of the Morea: Vernacular Architecture of the Northwest Peloponnesos (1205-1955), The Archaeology of Xenitia: Greek Immigration and Material Culture , Punk Archaeology, “Byzantium and the Avant-Garde: Excavations at Corinth, 1920s-1930s,” “If Space Remotely Matters: Camped in Greece’s Contingent Countryside,” and “North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in the Bakken Oil Fields.”

Works Cited

Arcadia. 2016. Arcadia Publishing website, https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/arcadia-publishing-books.

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Bucuvalas, Tina, ed. 2019. Greek Music in America. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Caraveli, Anna. 1985. Scattered in Foreign Lands: A Greek Village in Baltimore. Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art. https://issuu.com/olymbitis/docs/scattered_in_foreign_lands

Doulis, Thomas. 1977. A Surge to the Sea: The Greeks in Oregon. Portland, Or.: J. Lockie.

Gallant, Thomas. 2009. “Tales from the Dark Side: Transnational Migration, the Underworld and the ‘Other’ Greeks of the Diaspora.” In Greek Diaspora and Migration since 1700: Society, Politics and Culture, edited by Dimitris Tziovas, 17–29. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Huyssen, Andreas. 2000. “Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia.” Public Culture 12 (1): 21–38.

Kallianiotis Niko J. 2018. America in a Trance. Bologna, Italy: Damiani.

Liontis, Kostis. 2013. “Ο φωτογράφος του χωριού.” In Η ελληνική φωτογραφία και η φωτογραφία στην Ελλάδα: Μια ανθολογία κειμένων , edited by Eraklis Papaioannou, 57–63. Athens: Nefeli.

Manos, Constantine. 1972. A Greek Portfolio. New York: Viking.

Manos, Constantine. 1995. American Color. New York: W. W. Norton.

Marketou, Jenny. 1987. The Great Longing: The Greeks of Astoria. Athens: Kedros.

Moraites, Maria, and Stewart Hagmann. 1962. Goodnight, Socrates. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BKEKLl1GOUw.

Moses, Doreen. 1981. A Village in Baltimore: Images of Greek-American Women, Washington, D.C.: D. Moses. https://archive.org/details/avillageinbaltimoreimagesofgreekamericanwomen/avillageinbaltimoreimagesofgreekamericanwomen1/avillageinbaltimoreimagesofgreekamericanwomen1.mov.

Rice, Mark. 2009. “Arcadian Visions of the Past.” The Columbia Journal of American Studies 9: 7–26.

Sampas, Charles G., Leo Panas, and Charles Nikitopoulos. 1983. The First Greek Immigrants in Lowell, Massachusetts: A Photo Documentary 1900-1940 . Lowell, Ma.: PO Box 535, Lowell.

Sante, Luc. 2003. Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Sekula, Allan. 1982. “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning.” In Thinking Photography, edited by Victor Burgin, 84–109. London: Macmillan Press.

Steichen, Edward, ed. 1955. The Family of Man. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

The MGSA Greek American Resources Archive. Founded and compiled by Yiorgos Anagnostou, 2011. Annually updated by MGSA’s Transnational Studies Committee. https://www.mgsa.org/Resources/gkam.html.

Varajon, Sydney. 2017. “Interview with Tina Bucuvalas.” Ergon: Greek/American Arts and Letters. December 19. https://ergon.scienzine.com/article/interviews/interview-with-tina-bucuvalas