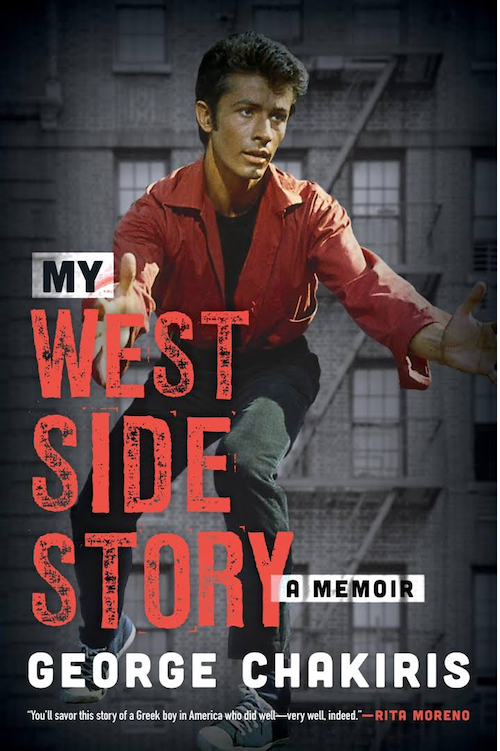

George Chakiris with Lindsay Harrison, My West Side Story: A Memoir. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press 2021. Pp x + 222. Paperback. $24.95.

A Review Essay

by Frank Hess

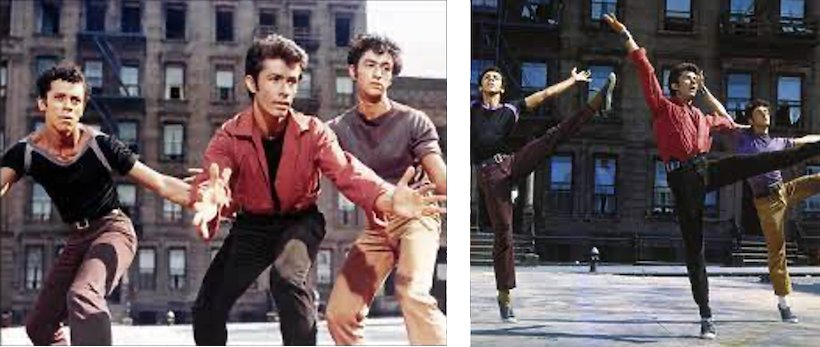

In many ways George Chakiris, the Greek American actor and dancer of West Side Story fame, led a charmed life. Born in 1932 to first-generation Greek American parents who had emigrated from the Ottoman Empire, Chakiris demonstrated talent as a youngster first in song and then in dance and, with the blessing of his parents, managed to parlay that talent into a seven-decade career in the entertainment industry. His career culminated with the role of the Puerto Rican gang leader Bernardo in the Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise’s 1961 film version of West Side Story, perhaps the most consequential text about ethnic American experience of the second half of the 20th century. For his performance, Chakiris was awarded both an Oscar and a Golden Globe as best supporting actor. Though his career never again reached the lofty heights that it did in the early 1960s, Chakiris remained an in-demand actor for decades and rose to become an A-list Hollywood celebrity.

Released to coincide with Steven Spielberg’s 2021 remake of West Side Story, Chakiris’s autobiography My West Side Story: A Memoir promises to be fertile terrain for reflecting on the nature of ethnic American experience in the 20th century. The cover art—a still of an athletic Chakiris in brownface1 as Bernardo, taken from one of the film’s warrior dance scenes—suggests an awareness of the complex intersections that exist between race, ethnicity, and gender in American society. Neither Chakiris nor his co-author Lindsay Harrison, however, seem willing to plunge into the difficult questions that a production like West Side Story or a career like Chakiris’s raise: what did it feel like to be a member of a less marginalized ethnic group such as Greek Americans representing a more marginalized ethnic group like Puerto Ricans in an era when ethnic stereotypes were not only prevalent, but openly voiced? Were there aspects of his own experience as a Greek American or of his family’s experience in Asia Minor that Chakiris drew on to craft his depiction of Bernardo? Did he reflect on the role that West Side Story played in humanizing ethnic American experience including Greek American experience? Was he cognizant of limitations in West Side Story’s approach to representing ethnicity? Did he feel that he was typecast as a result of his success as Bernardo? The book elides these questions, though it does offer some tantalizing tidbits of story that might have been more fully told.

To be clear, Chakiris does not ignore his Greek American identity in My West Side Story, but neither does he give it emphasis or reflect on it in the sustained ways that an academic audience would desire. Instead, we are able to glean morsels, mostly from the first chapter: that his grandfather arranged marriages for his two sons by travelling to Asia Minor and bringing back two young women from his village; that his father and mother decided to leave the patriarchally organized family confectionary and beer garden in Norwood, Ohio, to set out on their own, first in Tucson and then in Long Beach; that Chakiris was pressured by Paramount to change his last name to Kerris, and that he even went along with it briefly, until the disappointment of having a dance scene with Cyd Charisse cut from Meet Me in Las Vegas shocked him back to his senses: “My name was George Chakiris from then on, commercial or not, ethnic or not, no apologies, take it or leave it” (35).

Given that Chakiris seems to have set out to write a more general memoir as opposed to a sustained reflection on the dynamics of race and ethnicity in 1960s Hollywood, I have some qualms about trying to wrangle My West Side Story into the analytical categories of academia. Nonetheless, it is illuminating to read My West Side Story through the prism of white ethnicity. A category produced in the context of ethnic revival, white ethnicity is a specific set of strategies for interacting with racial and cultural hierarchies in the United States. Though “racially denigrated and classified as non-white in the past,” white ethnics have been able to elevate themselves socially and economically by defining themselves, “against the backdrop of complex social and political struggles over assimilation and cultural preservation,” as a subcategory of whiteness (Anagnostou 2009, 2). According to this reading, My West Side Story, provides just enough information about the author’s ethnic past to acknowledge his upbringing and tantalize the reader with a bit of exoticism, but not enough to subvert the dominant narrative of assimilation and acceptance. In other words, Greek American experience in the book is severely delimited, confined largely to the first chapter, and not represented as an active, on-going concern in the author’s life, even though he maintained close relations with his parents and family throughout his life. Instead, the book spends far more time elaborating Chakiris’s interactions with a veritable who’s who of Hollywood celebrities during his seven decades of public life.

From this vantage point, it is hard not to see the book as a lost opportunity. West Side Story is a fascinating multicultural text, but its origins are only partially documented in the book. The brainchild of dancer Jerome Robbins, West Side Story was originally envisioned in the late 1940s as a theatrical musical: an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet that would be set against the backdrop of turf wars between Jewish and Catholic gangs in New York’s Lower East Side. It was to be titled East Side Story. Robbins recruited two other artists to the project, composer Leonard Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents. Because of the proximity to World War II and the Holocaust as well as other artistic commitments, this project never got off the ground. When they revisited it in the 1955, the ethnic fabric of the United States had begun to change. Tensions between the Anglo and Chicano populations in Los Angeles were prominent in the news, and the Great Migration of Puerto Ricans to New York had changed the demographics of the city. Against this backdrop, the musical was re-envisioned as a conflict between Puerto Rican and white gangs and retitled West Side Story. Stephen Sondheim was recruited to help with the lyrics, and by 1957 the play was searching for financial backers.

Initially, the search for financial backers proved fruitless: “No one wanted to invest in a Broadway show that featured a dark score, gang fights, and three murders, particularly at a time when Broadway was thriving with feel-good musicals like The Merry Widow, My Fair Lady, Damn Yankees, and Guys and Dolls” (46). In a moment of desperation, Sondheim reached out to Hal Prince, who had won Tony awards in 1955 and 1956 for The Pajama Game and Damn Yankees. The rest is history. The musical opened to a packed house on September 26, 1957. Approximately a year later, plans were being made for a British production, and, two years after that, a movie version.

This much of the story is told in My West Side Story. What is missing, however, is a thorough discussion of the role that ethnicity and race played in the evolution of the theatrical and cinematic versions of the play and a conversation about the way that West Side Story impacted the career arcs of its stars. The creative team behind the original musical—Robbins, Bernstein, Laurents, Sondheim, and Prince—were all members of the Jewish Diaspora that settled in New York. Bernstein’s soundtrack drew inspiration from both African American musical traditions (even though Blacks were not featured in the musical) and Latin rhythms, creating oppositions between the two that highlighted the tensions between the rival gangs. The casts of both the stage and film productions of the play featured a wide variety of ethnic Americans. The film’s cast, for instance, featured two other Greeks in addition to Chakiris, brother and sister Gus and Gina Trikonis; members of the Jewish Diaspora like David Winters and Eliot Feld; Japanese American Nobuko JoAnne Miyamoto; Russian American Natalie Wood (born Natasha Zacharenko to Russian émigré parents); Cuban American and Puerto Rican Yvonne Wilder; and, of course, the Puerto Rican Rita Moreno.

Chakiris and Harrisons’s account of the evolution of the play and subsequent film leaves many questions lingering: how did the artistic team that created West Side Story draw on their experiences as ethnic Americans to write, compose, choreograph, and cast the play and interpret their roles in it? Did non-Hispanic members of the Sharks, the play’s Puerto Rican gang, have any hesitancy about taking on roles that could have gone to Hispanic actors? Did cast members reflect on the potential social impact of the musical, which debuted as the Civil Rights Movement was gaining steam? Did they see it as being something more than entertainment?

Also absent is a probing discussion of the impact of the film on the career trajectories of the actors who took part in it. Rita Moreno, for instance, has complained about the lack and quality of Hollywood roles that came her way in the aftermath of her Oscar for West Side Story (Martin 2008, M1). One of a very limited number of actors to win an ETOG (an Emmy, a Tony, an Oscar, and a Grammy), Moreno and Hollywood were at an impasse for seven years after West Side Story because of the type and quality of roles that she was being offered due to her ethnicity. Chakiris acknowledges her complaining at the 1961 Oscar ceremony about the minor role she had in “some crappy war movie” (Cry of Battle, 1962, a film that she had agreed to play in before her Oscar for West Side Story). He also draws a distinction between his strategies for brooking disappointment and hers: “If you don’t want to know how Rita feels about something, don’t ask her!” (88).

Chakiris, himself, made a spate of Hollywood films in the immediate aftermath his success in West Side Story. He starred as an Anglo American, 2nd Lieutenant John Gregg, in the WWII drama Flight from Ashiya (released in 1964, but shot in 1961) with Richard Widemark and Yul Brynner, who played the Japanese American Master Sergeant Mike Takashima. He also had a significant role as a native Hawaiian, Dr. Dean Kahan, in Diamond Head (1962), a drama about race and romance in multi-ethnic Hawaii that starred Charlton Heston as a wealthy white landowner who objects to his sister marrying a native Hawaiian—Dean Kahan’s brother, Paul, played by Italian American James Darren—all the while carrying on a love affair with an Asian woman that results in a child than he initially refuses to recognize. A starring role as a Norwegian pilot in another WWII drama, 633 Squadron, followed, as did a leading role as a Mayan prince exiled to Florida in Kings of the Sun, a costume drama set in the early 13th century CE at the time of Hunac Ceel’s conquest of Chichen Itza that also starred Yul Brynner as a Native American Chief in Florida. Subsequently, Hollywood roles dried up, and Chakiris was forced to pursue his film acting career in Italy, Britain, and France before returning to the United States for a string of mostly fairly minor television appearances that continued until quite recently.

The cultural politics of these films is almost entirely ignored. Diamond Head, for instance, is barely mentioned in My West Side Story, and Chakiris has little to say about what film critic and author Michael Atkinson (2013) has described as “the Hollywood reflex to cast patently un-native actors like Darren and Chakiris as Polynesians, and then surround them with fake-exotic examples of Hawaiian culture (dances, chants, aphorisms, legends).” Today, a film like Diamond Head certainly seems “ridiculous,” and its representational politics are decidedly problematic. I can understand why Chakiris might not want to probe too deeply into the film, but his silence also represents a tremendous lost opportunity. As Atkinson argues, Diamond Head was actually progressive for the early 1960s and an “overt protest against colonialism and white privilege” that occurred in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. He further suggests that it should be understood as an “earnest baby step the Industry made toward acknowledging, assimilating and celebrating ethnic paradigms that seemed foreign and primitive to the majority of white moviegoers.” I, for one, would have been extremely interested to hear an insider’s perspective on the changing politics of ethnic and racial representation of Hollywood during the Civil Rights era.

As I mentioned earlier, “white ethnicity” is one prism through which My West Side Story might be read. There is a second prism through which Chakiris’s book might be read and that is Chakiris himself: his personality, his motivations, his ways of being in the world. Throughout the book, he comes across as an incredibly decent, modest, and caring man who has genuine affection for almost everyone in his life from family and friends to colleagues and the raft of directors, choreographers, and producers who shaped his career. He paints a bleak picture of one agent who mismanaged his career in the early 1960s, Ruth Aarons, but even here he goes to great lengths to explain that he is doing this “not to indict her but to offer a cautionary tale for anyone who like me lets their naïveté prevent them from putting up boundaries” (96). Chakiris also comes across as an intensely private individual. He admits to having a few platonic crushes on actresses, but the book is anything but a kiss-and-tell memoir. He says absolutely nothing about the loves and passions of his life or his decision to remain a bachelor his entire life.

At the intersection of these two prisms, I would like to offer a third reading, one that potentially expands our understanding of white ethnicity. I see Chakiris’s caution, in part, as an indication of the fragility of the category of whiteness for ethnic Americans. White ethnicity is purchased by conformity to certain cultural norms, and the possibility of slipping back into racialized identity was and is a tangible danger for the white ethnic during the Civil Rights and post-Civil-Rights era. I also see Chakiris’s caution—about race and ethnicity and sex and sexuality—as evidence of the way that social factors—like family relations, friendships, social status—interpellate the white ethnic subject and make frank discussions about race and ethnicity and a host of other topics a challenge. Chakiris, in other words, seems to be an extremely loyal son, brother, friend, and colleague. He is highly considerate of the feelings and sensitivities of those around him. These are admirable personality traits and highly valued, for good reason, in our culture. They also dampen the sort of self-exploration that a scintillating memoir requires because consideration for the feelings of others mitigates against a more open discussion of the way that society and its institutions facilitate and limit career trajectories, personal fulfillment, and self-expression. Chakiris dances around these difficult questions, but I can’t blame him too much for doing so. To do otherwise would be untrue to the life that he lived and the friendships that he formed.

December 2022

Franklin L. Hess is a Senior Lecturer at Indiana University Bloomington, where he is the Coordinator of the Modern Greek Program and the Director of the Institute for European Studies. His research focuses on Greek popular culture, including film, television, music, and cuisine. His work explores the intersection of geopolitics and culture.

Notes

1. Chakiris was actually selected for the role of Bernardo in part because of his skin tone, but he was light-skinned enough that he had no problem playing the role of Riff, the leader of the rival white gang, the Jets, in the English stage production of the musical, which ran from December 1958 through January 1962 in Manchester and London.

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos, Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2009.

Atkinson, Michael Atkinson, “Diamond Head,” June 3, 2013, https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/73053/diamond-head#articles-reviews?articleId=636580 (accessed November 11, 2022). [To access the article, click on the link, then select “Articles and Reviews” from the menu on the left, followed by “Featured Article.”]

Martin, Lydia, “Rita Moreno Overcame Hispanic Stereotypes to Achieve Stardom,” 14 September, 2008, The Miami Herald, p. M1.