Transnational Migrants: A Reappraisal of Ioanna Laliotou’s Transatlantic Subjects

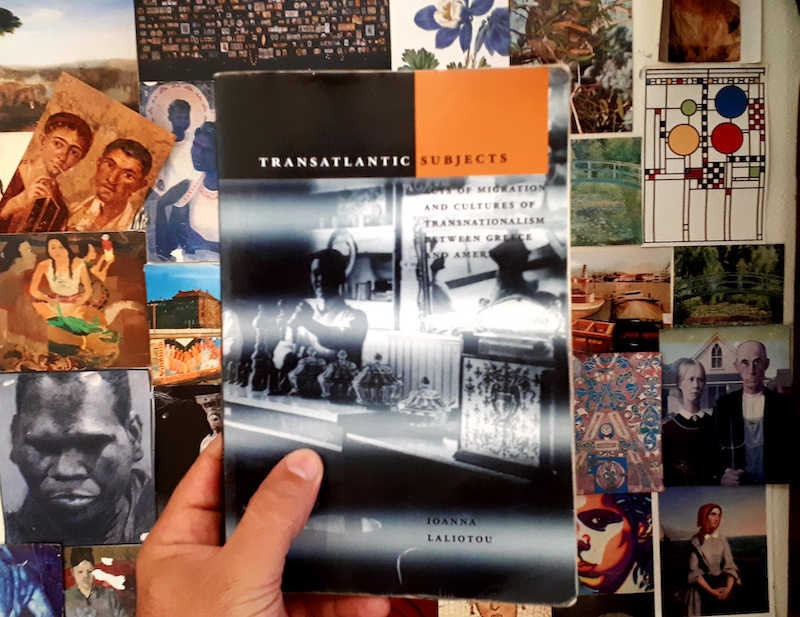

Ioanna Laliotou, Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America. Chicago: Chicago University Press. 2004. pp. 248. Paper $34.00

A Review Essay

By Andonis Piperoglou

Three years ago, a senior historian shared some invaluable advice on how to ready my doctoral thesis for publication. My thesis, he suggested, would be significantly enhanced by a “deeply informed” engagement with Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America by Ioanna Laliotou. Aside from the obvious differences in geographical focus, it became apparent that my thesis—Greek Settlers: Race, Labour and the Making of White Australia, 1890s-1920s —paralleled Laliotou’s refreshing approach to historical inquiry, which breaks free from the limitations of the nation-centric migration histories that have long dominated the field.

Acknowledging what my senior colleague termed as a “lacuna” in my research, I immediately made an online purchase. Some weeks later, after travelling across the Pacific via airfreight, Transatlantic Subjects arrived at my Australian doorstep. I was eager to see the text in physical form, and the book instantly captured my attention. Its cover page—depicting a man smiling behind the counter of a Greek-run confectionary store in the United States—reminded me of similar historical photographs I had seen of Greek shopkeepers in Australia.1 The visual likeness, and the overwhelming intimation that these Greek migrants had shared a common experience, despite having settled at opposite ends of the globe, resonated deeply with me. I enthusiastically scribbled in the book’s margins. I underlined arresting idioms. I energetically highlighted passages that seemed to hauntingly capture thoughts that I had pondered over for many years. I was hooked.

Transatlantic Subjects is a cultural history about Greek migration that advances the historical imagination. Offering a new language in which to think about the distant migrant past, the book simultaneously privileges the “transnational turn” and “migrant subjectivity” in historical practice. Defining migration as a transnational “act,” it locates migrant expressions in the form of autobiographies, parades and essays to inform us that cultural entanglements circulated between Greece and the United States during the first half of the twentieth century. For me, Laliotou’s book is a richly detailed, theoretically sophisticated, and thought-provoking text. It reads against the grain of hegemonic narratives about migration and does so by acknowledging the complex historical phenomenon of human mobility and connecting such mobility to the historical interplay of cosmopolitanism, globalization, and nationalism. Admittedly, I was bemused (and somewhat embarrassed) that I had not accessed and studied it before. Transatlantic Subjects now holds pride of place on my bookshelf. When I feel the need to return to it—which, as a cultural historian who examines the dynamics of migration, is a common occurrence—I silently thank my senior colleague for drawing it to my attention. It is a book that demands to be read and revisited. It is a book that propels me to think about the historical processes of migration anew.

Some history books standout for the depth of research and the new narratives they provide. Other histories standout for the ideas they generate, the connections they make with other disciplines, and the new vistas that they open for their readers. Sixteen years since its publication, Transatlantic Subjects is an excellent example of the latter. But, sadly, this innovative historiographical landmark has not garnered the recognition it deserves, at least in English language scholarship, receiving only a limited range of academic attention and review.2 Now, as the subject of migration and migrant experiences has taken on a new immediacy and importance on the global stage, and in Greece in particular, I find myself reengaging with this book. The following discussion then, returns to the book to contemplate its enduring value to historical researchers who are interested in the dynamism of Greek (and other) migrant pasts.

By creating a multilayered history through selected stories drawn from a diverse archive, Transatlantic Subjects allows its migrant subjects to retain a refreshing level of personal agency. By claiming that migration from Greek speaking areas in the Mediterranean region to the United States created new forms of social relations, the book reveals an underexplored migratory dynamic that has been overlooked, misunderstood, or ignored by conventional historical approaches. Thinking about migration and culture transnationally, Laliotou engages with a thought-provoking and fruitful methodological and theoretical intersection. She brings the methods of transnational history into conversation with the charged concept of subjectivity. Fiona Paisley and Pamela Scully argue that, as a form of historical practice, transnational history displaces “the constraints and distortions of ‘national history,’” replacing them “with a larger and more complex perspective on the historical formations of subjects and places, systems of power and authority, [and] cosmopolitan or worldly identity politics”(2019, 189). Subjectivity, on the other hand, as a loaded conceptual term has been understood by cultural historian Luisa Passerini as a historical process that should not be reduced to a single linear story (2000). Organizing her research around these two major scholarly axes, Laliotou develops transnational historical research methods to create a multifaceted history that is worthy of reappraisal today because it speaks to questions about how we relate to the past through the present. For example, when Laliotou examines how portrayals of migrants as threatening outsiders who invade otherwise secure borders have been historically constituted, she interrogates how such negative portrayals influenced the identity formations of migrants during the course of the twentieth century, providing crucial context for how we approach and discuss the issue of migrancy in the present.

The dual historical investment in transnationalism and subjectivity in Transatlantic Subjects is examined within three distinct parts: the first focuses on “The Immigration Problem” as a central issue of political, legal and cultural concern at the turn of the twentieth century; the second on “Imagination” explores creative forms of diasporic cultural production that was expressed in popular fiction and public performances; and the third on “Mnemonics” explores the role that differing modes of memory preservation, like the telling of one’s life story either as a memoir or oral history, played in developing a professional historiography of migration. Each section focuses on different types of texts and mobilizes distinct theoretical terminologies for analysis. Phrases like “situational entanglements of migrancy” and “migrants’ self-conceptualizations,” for example, allow readers to see how detailed attention to specific uses of language has the potential to reinvigorate the writing of Greek migration history (Laliotou 2004, 17, 76). By honing in on migrants’ self-conceptualizations, we are guided to think about how migrants conceived themselves in relation to entangled cultural settings and affiliations. This approach is well suited to Laliotou’s purpose as it permits us to refocus our gaze away from histories of migrant actions (like departure, arrival and settlement) and towards a history that privileges the structured meanings that migrants gave to their experiences. In adopting a theoretical language, however, Laliotou exposes the frustrating impediments that theoretically inclined historians face in conveying the complexity of migrant identifications in a way that does not simplify or generalize. Too often, clear and concise communication is supplanted, for example, by loaded theoretical terms that the average reader (particularly in the everyday non-academic audience, including the broader Greek American public) might find obscure and overly specialist. Striking a balance between digestible prose and the usefulness of theory, Laliotou italicizes terms like “circuits of subjectivation” and “becoming” (12), suggesting to her readers to critically probe into how theoretical language can inform migration history.

Breaking from conventional chronological historical framings, the three parts of Transatlantic Subjects each comprise of two chapters. The first and second chapters examine racial thinking in the United States and how governments and public intellectuals on either side of the Atlantic struggled to come to terms with the phenomenon of migration from the Mediterranean region during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The third and fourth chapters explore literary and performative representations of Greek migrancy, while the fifth and sixth chapters engage with biographies and autobiographies of migrants written in Greece and in the United States as well as the historiography of Greek America. While all of these examinations offer valuable insights, it is the analysis on migrant performance, where the strengths of Transatlantic Subjects caught my attention most prominently. Exploring what she terms “the exhibition of subjectivity,” Lailotou reveals, for example, how migrants’ creative engagements with Fourth of July parades in 1918 became a means to spectacularly represent both Greek national sentiment and loyalty to the United States (124). Representing a historical shift in the way that migrants participated in social, political and cultural exchanges, such performative practices demonstrated how migrants desired to publicly present themselves to mainstream U.S society, while also revealing how they wished to be acknowledged in ways that characterized their transnational identifications with both Greece and the United States.

For Laliotou, transnational history takes historically informed readers out of their comfort zone by challenging the common assumption that history should tell the story of the nation. Yet, despite being attuned to the realities of the interconnectedness of past worlds, the potential of transnational history has not been fully embraced by historians interested in Greek migration. The intellectual imperative of adopting a transnational perspective on the past—to demonstrate how migrants facilitated the circulation of emotions, capital and ideas that literally and imaginatively tied their new home country to their historical homeland—fails to satisfy the political demand for a history that serves the national story. Thus, one U.S.-based reviewer, Dan Georgakas, has criticized the book for not successfully capturing the “totality of the Greek experience in America” and presenting a “very European look at Greek emigration to America” (2005, 37–38). Another review in the Greek newspaper, Ta Nea, by Dimitris Papanikolaou (2006), argues that Laliotou overemphasises the fluid and in-between facets of migrant subjectivity, neglects to take into account that some migrants, particularly diasporic elites, maintained static forms of affiliation that were anchored in old world traditions. Papanikolaou questions Laliotou’s depiction of the contemporary relevance of Greek migrant pasts and wonders why nostalgic attitudes towards the migrants of the last century holds such prominence in contemporary Greece. It is because, he proposes, that the “silent majority” of the Greek public recognizes past Greek migrants and even Greek Americans as the protectors of traditional forms of Greekness. This imaginary of an undiluted Greekness, he concludes, steers away from the realities of a rapidly changing, diversifying modern Greece that occurred (and is occurring) due to the arrival and settlement of migrants into the country. With its focus on transnationalism and subjectivity, Transatlantic Subjects seems to have perplexed some readers, who perhaps expect histories of migration to be all encompassing. Laliotou steers clear of telling an all-inclusive account of the past. By not aspiring to be comprehensive, she stands for a transnational historical approach that can help us reframe the history of Greek “migration in wider continental contexts that supersede the nation-state … [allowing] us to understand more fully the impact and structure of populations flows without relating the phenomenon exclusively to separate national interests” (6).

It would be wrong, however, to conclude that Laliotou’s transnational history, in elevating the individual over the nation-state, carries no political imperative. On the contrary, as a politically minded form of history, Transatlantic Subjects promotes and engages with the idea that migration and migrants—with their complicated set of negotiations, multilayered realities, and multi-directional orientations—raises new questions about what stands for history and who can count as historical subjects. In other words, by framing migrants as active historical subjects Laliotou develops a form of historical research that not only position migrants as active historical players, but also positions human movement—instead of stasis—as a normative phenomenon of modern and contemporary history. Taking migrant self-representations in literature as a serious category of analysis, we might view Laliotou’s use of literary evidence as an innovative form of transnational historical research and writing.

Laliotou’s use of literary evidence invites readers to consider how migration and writing share an interrelated past. While its status as a form of artistic representation has led some historians to question the legitimacy of literary fiction as a reliable source, Laliotou shows us that, with rigorous contextualization, literature can not only be a valid and reliable form of historical evidence, but also that it can offer a valuable entry point into the political and emotional processes of migrant pasts. Transatlantic Subjects, for example, opens with a literary representation of a Greek migrant experience by quoting a passage from Gold in the Streets, a novel written by Mary Vardoulakis and published in 1945. The novel narrates the story of a Greek migrant community in Chicopee, Massachusetts, and the scene Laliotou shares with the reader showcases how downtrodden Greek laborers developed a self-perception of themselves as migrants that was “derived from a bilateral process of recognition”—a process of recognition that is loaded with how an individual might perceive themselves when relocating to a new land and how that individual might be perceived by others in that land (2).

By identifying literary dynamics in migrant worlds—dynamics that involved prolific networks of writers, publishers, distributors, and readers—Laliotou reveals that literature enabled a new form of sociality to evolve. This was a form of sociality in which migrants could publicly express themselves to mainstream onlookers while simultaneously representing themselves to each other. Indeed, Laliotou’s use of literary evidence is so insightful that it reveals the need for further historical research on how migrant writings (be they novels, personal essays, plays, scripts, diary entries or social media posts) are often a vital component to how some migrants come to understand and assert themselves as multiply located subjects. Laliotou has a knack for offering clear, concise summaries of migrant texts and her summaries encourage readers to consider the various genres of migrant writings as constitutive of migrant identity formation.

For Laliotou, the complex story of the migrant experience can only be accessed by the selective rereading of dispersed historical materials that document the history of migration and migrant communities. These materials—novels, autobiographical writings, history books, photographs—register as examples of new forms of cultural expression that emerged as a result of the dense flows of people, culture, and capital that circulated across the globe during the first half of the twentieth century. In writing a transnational history that centers migrant subjectivity, Laliotou manages to capture the importance of working with archives located in many national settings, while also developing a historical approach that carries political relevance for our own contemporary moment. For instance, she opens and closes her book by arguing that the historical view of migrants as threatening outsiders needs to be rethought, particularly because human movement today is not an anomaly but a norm in which cultural difference becomes part of the nation. She is clearly passionate about the contemporary relevance of her research, and expresses the hope that her history of Greek migration may “enact difference” in this fractious yet interconnected contemporary era (200). This political positioning might seem at odds with more conventional histories of migration that favor linear story telling techniques, make broader claims toward objectivity, and tend to produce assimilationist narratives of the past that are more digestible and popularly accessible. Certainly, more conventional histories have their place and value, but Laliotou’s alternative approach has a different set of benefits that supplements and extends historical knowledge about migration.

Through her focus on “migrant subjectivity,” Laliotou endeavours to show us that the “Greek migrant” during the first half of the twentieth century was a “recognizable subject,” who experienced antimigrant nativism (10, 13). Yet, she also wishes to inform her readers how Greek migrants’ sense of self was related to and rooted in multiple places and cultures. This is not the story of migration that we have become accustomed to in migrant historiography. Assimilation, a dominant feature of “immigration history,” is not a key focus of Laliotou’s analysis. Neither is what she calls the “obsession of American historiography” (8) of situating migrants—whatever their place of origin—as contributors to nation-building endeavours. Instead, Laliotou presents us with an historical approach that reveals the limitations of nationalist interpretations of migration. Her discussion of the autobiographical writing of author and journalist Demetra Vaka-Brown, as Yiorgos Kalogeras notes in his assessment of the book in The International Migration Review, reveals how a life experience in Balkan, Ottoman, American, and European worlds offers us “transgressive” example of how migrant identifications are formed between and across nation-sates, oceans, and empires (2005, 156).

By complicating the “outside-within” (201) status and identifications of Greek migrants, Transatlantic Subjects argues that the mobile lives of Greek migrants involved many intersecting cultural settings that were linked to, yet often transcended, the nation-state. For instance, Laliotou uses the formation of “Gringlish (Greek and English),” in which English words entered into the Greek language, or the movement of musicians, records, tunes, and capital between Athens, Istanbul, Smyrna and the United States, as emblematic examples of how social relations enacted by migrants emerge within a system of transnational circulation and transferral (129–131). Musical sound, for instance, could be recorded in Mediterranean tavernas and listened to in migrant homes in Philadelphia. Likewise, tunes could be recorded in Philadelphian studios and sent to Mediterranean shores for consumption.

While, in my view, Laliotou’s focus on the subjective experience of transnational migration is a welcome innovation because it emphasizes the importance of the complexity in migrant life-worlds, critical responses to this aspect of her work has been mixed. In his 2006 review of Transatlantic Subjects in the American Historical Review, the late historian of immigration Victor Greene praised Laliotou’s work as a “pioneering study on the important topic of immigrant mentality” (2006, 440). The personal dynamics of transitioning from a place of departure to a place of arrival, according to Greene, had never been explored with “the full and extended attention and theoretical analysis” that Laliotou devotes to the topic. Yet, as Georgakas notes in his Journal of American History review, the book’s “dense theoretical language” may be an impediment for non-specialized readers (2005, 637). For Georgakas, Laliotou would have done well to explore how the transnational dynamics of migrancy may have influenced how second-generation Greek Americans wrote about their parents’ U.S. experiences. Drawing upon the proliferation of literary texts and memoirs that have been written by subsequent generations, this approach would certainly offer new insights into not just migrant subjectivity, but also what we might think of as ethnic subjectivity.

Migration historian Donna Gabaccia writes in her review of the book in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies, that Transatlantic Subjects contributes to the coalescing field of migration studies, noting that Laliotou aspired to make such a contribution. But, Gabaccia worries that even readers who would appreciate Laliotou’s interdisciplinary aspirations must be prepared to squint at “inadequate, puzzling, or simply incorrect … summaries, critiques and ‘straw man’ dismissals,” often without adequate references to the exhaustive historiography on Atlantic migrations (2005, 402). Even readers who appreciate the difficulties of mastering more than one national historiography (as I certainly do as a scholar of Greek migration to Australia), will find that Laliotou at times falls short. For example, she believes that her transatlantic focus on Greece should be buttressed by an understanding of the case of Italy and its mobile populations. However, according to Gabaccia— an expert of Italian migration—Laliotou’s reading of the sizeable literature on Italian migration is both limited and dated. Gabbacia’s criticism is warranted because Laliotou could have easily achieved a greater breadth of historical comparison, particularly as histories of Italian migration have been one of the most vibrant and comprehensive subfields in immigration and ethnic history. That Laliotou compares Italian migration with Greek migration to the United States, however, is a fact with some significance. As comparable migrants from the Mediterranean region who arrived to the United States, the commonality of experience shared between Italians and Greeks is noteworthy. Yet such a comparation suggests (at least to me as a historian interested in the transnational dynamics of Mediterranean migrations across British-worlds) that more thought might be given to how U.S.-oriented migrant pasts could be analyzed alongside migration flows to other English-speaking countries, like Canada, South Africa or Australia. Although Laliotou’s engagement with Italian migration in relation to Greek migration is rather cursory, her comparative analysis nevertheless extends the potential of what transnational history can be.

The book’s predominant focus on subjectivity, a term that Laliotou herself claims is “overcharged and occasionally vague” (9), may explain why some historians felt uncomfortable with the text’s loaded theoretical language. Having said this, Transatlantic Subjects has made a significant impact on migration studies—a scholarly vantage point that during the time of the book’s publication, as Gabaccia aptly noted in her critical review, was very much a “field-in-the-making” (2005, 399). At present, however, it might be safe to say that “migration studies,” has crystalized into a distinct discipline that is interested in more recent migratory dynamics when compared to historical studies that explore migration. As a distinctive interdisciplinary area of scholarly research, Transatlantic Subjects has contributed to its growth, especially when studies focus on subjective experiences.3 Fragmented as it might be by national, spatial, linguistic, and disciplinary boundaries, the field of migration studies, like the transnational turn in historical inquiry, has become a distinct space of scholarly inquiry that is opening up fresh insights into the complexity of migration flows. Exactly what this means for the history of Greek migration is unclear. What is clear, however, is that historical studies of Greek migration can still gain much from the transnational turn pioneered by Transatlantic Subjects.

In a world of increased circulation, exchange and connectivity Laliotou’s Transatlantic Subjects has obvious contemporary relevance. As a history that is loaded with examples of how migrants mediate between worlds, the book allows us to consider how one might deliver the promise of transnational history. Might a transnational approach of Greek migration gloss over pervasive imperial structures, lingering regional identifications, or connected global phenomena? Are some matters—like the dynamics of race in Greek Australia, the politics of Christian Orthodoxy in North America, or the role of social media in facilitating conversations that span across Greek worlds—more amenable to historical inquiry that takes into account the invasiveness of imperialism, the geographical importance of regionalism, or the way historical connections are formed across digital diasporic platforms? It is a tribute to Transatlantic Subjects historical intervention that we are stimulated to ask such questions.

Laliotou’s transnational approach to the study of Greek migration reveals the interpretive benefits, as well as the current difficulties, of writing transnational histories of migration in a way that is digestible to the public and academic readers alike. Moreover, Transatlantic Subjects forces us to question what it means to do, or to advocate for, transnational histories of Greek migration, whether we focus on the United States as a site of analysis or elsewhere, like Australia or Canada, where many other scholars of Greek migration work and reside.

Through its study of migrant subjectivity, as it were, of the “multiple shapes of Greek culture,” Laliotou’s Transatlantic Subjects offers a way of thinking about migrant pasts that is compelling and provocative (200). It encourages historians, like myself, to explore the interconnectedness of past lives, to reconsider the historical processes and relationships that joined Athens to New York via the port cities of the Mediterranean, Crete to Colorado via extensive and exploitative labor networks, and Corinth to Chicago via melancholic folksongs. If one’s historical subject is the cultural dynamics of migration a transnational approach is fruitful, necessary even, for better understanding the subjectivities that the phenomenon of migration could produce.

To conclude, the impact of the transnational turn in studies of Greek migration of which Transatlantic Subjects is an early and innovative proponent can be measured by its disparagement by scholars who have not fully understood Laliotou’s intervention. The book is a redefining work of migration history that has not received the attention and consideration it deserves. Turning its pages in Australia has opened my historical outlook. Like most migration histories, Transatlantic Subjects operates at a highly empathetic and intellectual level, providing an interesting illustration of how human mobility has operated on a transnational spectrum onto which the subjectivities of migrants can be mapped. Transatlantic Subjects does not supplant or devalue national histories of migration. Rather, it reorients our gaze, thereby allowing us to view national pasts as a result of wider historical processes, probing us to introduce different stories that have been excluded in linear representations of the nation. Although thinking transnationally arguably provides a richer and more complex account of the past, it poses no discursive threat to the continuing political power of the nation-state in the present and foreseeable future. Even as it becomes more interesting and exciting in its ventures into the wider world, transnational historical studies about Greek migration will not simply relinquish the domestic power that comes with consorting with the nation-state. At this moment when the issues of past and present migrations have an immediate relevance, Transatlantic Subjects is a text that should be read and reread the world over.

Andonis Piperoglou

is a

Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Griffith Centre for Social and

Cultural Research, Griffith University (Brisbane, Australia). He is a cultural historian

interested in connections between settler colonialism, ethnicity, and

migrations between the Mediterranean and the Pacific.

Notes

1. For an insight into historical photographs that depict Greek migrants in Australia see Alexakis and Janiszewski (2007, 1998).

2. It was Yiorgos Anagnostou, editor at Ergon, who encouraged me to reappraise Transatlantic Subjects. His invitation propelled me to consider why the book has perhaps been misunderstood by its critics and unduly neglected by historians since its publication. I should note that Transatlantic Subjects was translated into Greek, in 2006 .

3. Works in migration studies that have drawn upon Laliotou’s Transatlantic Subjects include Levitt and Jaworsky (2007), Cabot (2014), and Latham (2010).

Works Cited

Alexakis, Effy, and Leonard Janiszewski. 2007. Greek Cafes and Milk Bars of Australia. Sydney, Australia: Halstead Press.

– – –. 1988. In Their Own Image: Greek Australians, Sydney, Australia: Hale and Iremonger.

Cabot, Health. 2014. On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Gabaccia, Donna. 2005. Review of Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America , by Ioanna Laliotou, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 23 (2) (October): 399–402.

Greene, Victor. 2006. Review of Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America , by Ioanna Laliotou, The American Historical Review, 111 (2) (April): 404–41.

Georgakas, Dan. 2005. Review of Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America , by Ioanna Laliotou, The Journal of American History, 92 (2) (September): 637–38.

Kalogeras, Yiorgos. 2005. Review of Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America , by Ioanna Laliotou, International Migration Review, 39 (2) (June): 516.

Latham, Robert. 2010. “Border Formations: Security and Subjectivity at the Border,” Citizenship Studies, 14 (2) (April): 185–201.

Levitt, Peggy, and B. Nadya Jaworsky. 2007. “Transnational Migration Studies: Past Developments and Future Trends,” Annual Review of Sociology, 33 (August): 129–56.

Paisley, Fiona, and Pamela Scully. 2019. Writing Transnational History. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Papanikolalou, Dimitris. 2006. Review of Transatlantic Subjects: Acts of Migration and Cultures of Transnationalism Between Greece and America , by Ioanna Laliotou. Ta Nea/Vivliodromio, 11 March.

Passerini, Luisa. 2000. “Becoming a Subject in the Time of the Death of the Subject,” paper given as the Fourth European Feminist Research Conference. Bologna (September). http://archeologia.women.it/user/4thfemconf/lunapark/passerini.htm

Piperoglou, Andonis. 2016. Greek Settlers: Race, Labour and the Making of White Australia, 1890s-1920s. PhD Thesis: La Trobe University.