A Conversation Broken Off In Mid-Sentence

A Remembrance of Poet Dean Kostos

by Vasiliki Katsarou

When I first heard the sad news that Dean had passed, l was taken aback. We hadn’t seen each other much in the last few years, and in fact I knew very little about his day-to-day life in New York, yet I always felt he was close, in a way that’s hard to explain.

I first met Dean in 2010, when he was the founder and host of the three decades long Greek American Writers’ Association Reading Series at the Cornelia Street Cafe. I’d been introduced by our mutual Greek friend, the poet Basil Rouskas. A few years earlier, Dean had edited and published an anthology of Greek American poetry called Pomegranate Seeds, with Somerset Hall Press, a small press based in Boston. This remarkable anthology was exhaustive, with close to fifty poets, and a thoughtful introduction by Dean.

Dean was a generous host, editor, and interlocutor. Two years later, in 2012, inspired by Dean's example, I'd founded my own poetry reading series at Panoply Books in Lambertville, and Dean kindly agreed to read from his collection, Rivering, one of at least eight full-length poetry collections that he published.

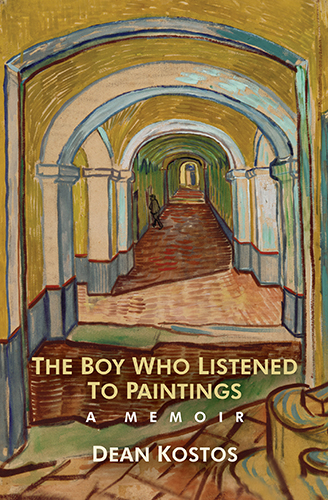

Dean was reserved about his family life. I gradually learned that he’d grown up in Cinnaminson, in southern New Jersey, where his father had been the mayor for a time. I was astonished by this. Coming from Andover, Massachusetts, and raised by an engineer father with a Greek accent, I couldn't imagine my own Greek father the mayor of my stodgy New England town. Dean didn’t share too many details about his family except to say his childhood had been an unhappy one. The story of his experience of bullying in a fractured family, which drove him to take refuge as a teenager at the psychiatric hospital known as The Institute of Philadelphia Hospital, is recounted in his harrowing 2018 memoir The Boy Who Listened to Paintings.

Anyone who has read Dean’s work knows that he was a brilliant poet, with exquisite diction, and exceptional knowledge of poetry forms. He had an MFA from Antioch University, and taught poetry at a number of New York-area colleges. Dean fervently believed that beauty could provide redemption from the many sorrows of the world. “Artists unearth beauty from brutality,” he writes in his poem “Wounds Wound with Poems” in the collection Pierced by Night-Colored Threads.

The poems in that book are breathtaking. All of his poetry evinces a deep love of visual art. In his introduction to Pomegranate Seeds, Dean wrote that he considered Greek mythology to be an “ur-Surrealism” and indeed much of his work is steeped in surreal or baroque imagery.

With each successive collection, Dean's poetry accumulated a dizzying array of references, from Greek mythology to the Egyptian Book of the Dead, to the Bhagavad Gita, the Kabbalah, and to Jung’s Red Book.

Dean was a spiritual seeker. Once, at the Cornelia Street Cafe, I introduced my own reading with a passage from Saint Gregory Nazianzus: “When the heart is seized by great joy, eagerness ‘unwinds the tongue’–strong emotion is expressed in words which, like a violet wind, enters the cracks to produce sound.”

Dean was moved by this, and questioned me about Nazianzus later on. He and I were both raised in the Greek Orthodox Church, and I suspect the estrangement from his family also led to some sort of estrangement from his Greek Orthodox roots. He seemed cheered to learn of a possible path back to his own tradition.

I hear an echo in the conclusion of his stunning persona poem “At a Revival Tent” (in the voice of Sojourner Truth!) from Pierced by Night-Colored Threads:

Transformed—neither woman nor man—

into a cleansing wind, I'll ripple like a cape.

Trilling with breaths of seraphim,

I'll sing, not singe, with choirs of saints and slaves

to climb the dark fortress of hymns,

to find the key, liberating the dead from graves.

One of the last times Dean and I were together in person was in New Hope, Pennsylvania, at Farley’s Bookshop where we gave a joint poetry reading. Dean told me how fond he was of New Hope because he’d come with his family on vacation many times as a child.

As we sat side by side atop the office desk in that dusty back room, our legs dangling over the side, I felt for a moment that we were siblings. Siblings in poetry, at least. Dean had recently read and commented on a newly assembled manuscript of mine (which I would later publish as two chapbooks). When I read his apt insights and enthusiastic observations now, I am especially grateful for the gift of Dean’s time and attention and exquisite sensibility. There was such a curious self-effacing quality to Dean. His sincere hope for connection to others through art was paired with a modest yet insistent belief in the power of his own words. He gave his all for his art.

A year or two into the Covid era, Dean and I hadn't been in touch, except when I received two brief and warm congratulatory messages: upon the publication of my chapbook Three Sea Stones, and then again when I founded Solitude Hill Press.

I tried to imagine Dean’s day-to-day urban life, in his Chelsea apartment that had been deeded to him by a relative. Dean had assembled his own chosen family, which was quite large, encompassing many fellow poets in greater New York City. Every year on his birthday in May, he organized a lunch at one of his favorite downtown restaurants (often Thai) and the invitation came in the form of a poem. Here is one:

Birthday Ghazal

As May springs back into bloom, I’m again

inviting friends to help me celebrate. Yes, it’s time again.

my birthday offers me the opportunity

to introduce friends who are sublime, again

As if scaling the rungs of a ladder, we’ve moved

through life's experiences. Let’s climb again

up from the #1 subway at 7th Avenue & 23rd Street.

Come to the Pongsri to toast with cider or wine, again.

The address is 165 West 23rd Street, between 6th and 7th Avenues.

We’ll meet at 8 o’clock. To miss would be a crime. Again,

Don’t worry about presents; your presence is all

that matters. The date’s Saturday, May 21st—spring’s prime,

again.

The ghazal, like a birthday, requires one to reflect:

I, Dean, grateful to chime again:

Thank you for your friendship!

Thank you for your friendship, Dean. I’ll miss you. May your memory be eternal.

A poet, editor, filmmaker, and publisher, Vasiliki Katsarou was raised in Massachusetts by Greek-born parents.

She is the author of a poetry collection, Memento Tsunami and two chapbooks, Three Sea Stones and The

Second Home (forthcoming). She holds an AB magna cum laude in comparative literature from Harvard University

and an MFA in filmmaking from Boston University. Her poetry has been published widely, and in translation

in NOON (Japan), Corbel Stone Press’ Contemporary Poetry Series (U.K.), Regime Journal (Australia),

Mediterranean Poetry (Denmark), and Mandragoras (Greece). One of her poems is archived in the permanent

collection of the Smithsonian. Her new small press is

Solitude Hill Press.