Caesar V. Mavratsas: Contributions to Greek American Sociology

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

The academic community sadly lost Caesar V. Mavratsas in 2017, prematurely, at the age of fifty-four. At the time of his passing, he was an associate professor at the University of Cyprus, in the department of Social and Political Sciences, in which, since his hire in 1995, he produced important work on Cypriot nationalism, a topic that preoccupied him both as a scholar and public intellectual. A dedicated teacher, Mavratsas was a staunch and often vigorous proponent of multicommunal coexistence as well as civil liberties on the island, and his interest in comparative ethnic studies, focusing on the Armenians and the Maronites of Cyprus, was lifelong.

This essay focuses not on his more celebrated work on Cypriot nationalism, society, and politics but rather on Mavratsas’s academic work on Greek America, most of it produced prior to his return to Cyprus in 1995. However belatedly—for the occasion that motivates this tribute could not have been more unfortunate—my engagement here hopes to recognize Caesar Mavratsas as a significant early career sociologist of Greek America, and more specifically, to acknowledge him as a theoretically informed and empirically grounded scholar who contributes to our understanding of Greek immigrant entrepreneurship in the United States and the impact of this economic culture on the formation of a socioeconomically distinct Greek American identity, as well as to emphasize his pioneering contributions to transnational modern Greek studies and to comparative analysis of world Hellenisms. In this writing I concentrate on his early comparative research on Greek American sociology, published between 1993 and 1995, to foreground the manner in which he advanced Greek American studies and the questions that his work raises for this academic field down to our days.

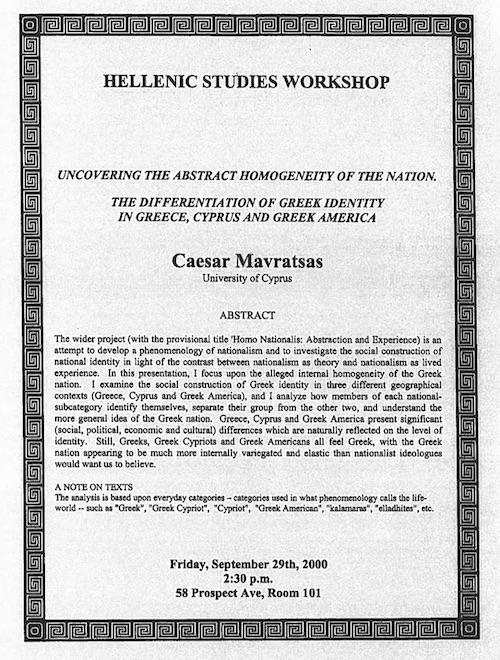

Given this professional trajectory it is not surprising that Mavratsas’s Greek American corpus is small: (1) a dissertation, entitled Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement. The Formation and Intergenerational Evolution of Greek-American Economic Culture (1993); (2) a book chapter, “Greek-American Economic Culture: The Intensification of Economic Life and a Parallel Process of Puritanization” (1995), which summarizes his dissertation findings; and (3) a journal article, “Cyprus, Greek America, and Greece: Comparative Issues in Rationalization, Embourgeoisement and the Modernization of Consciousness” (1995), which expands his comparative examination of Greek identity-making to include Cyprus. This interest resurfaced five years later, in his project as a visiting fellow in 2000 at the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, entitled, “Greek Identity in Greece, Cyprus and Greek America: From the Production to the Consumption of Nationalistic Ideology.” His talk at the center questioned the homogeneity that nationalism imposes on diverse Greek identities globally. Despite my efforts, I was not able to find evidence of any post-2000 publications or writings-on-file on this or any other Greek American topic.

Though small, this corpus advances Greek American sociology considerably. His research carries great potential, prompting the “what if” question: what if he had kept his focus on Greek American topics longer? Would he have stayed with Greek American studies had this field possessed greater marketability? If the academic community is lesser because of his passing, Greek American studies is certainly lesser for his reprioritization of scholarly interests. But it is disheartening too that, to the best of my knowledge, no scholar has engaged at the ethnographic level with the questions he raised so pointedly. Neither do we have follow-up studies of interethnic, intraethnic and intradiaspora comparativism that Mavratsas pursued to various degrees (sometimes comprehensively, sometimes partially, and sometimes tentatively). Regardless, and unfortunately, his work has been gravely neglected among Greek Americanists, even by those who have immediate stakes in a topic he placed at the center of his interests, namely intergenerational upward mobility, a process often referred to as the embourgeoisement of Greek America. In this respect, it is curious that his work is absent from the bibliography of the latest, 2014 updated edition of Charles Moskos’s Greek Americans: Struggle and Success, a book that as early as 1982 pioneered and subsequently popularized the embourgeoisement concept, making it a household name in Greek America. This commemorative essay seeks to correct this all-around neglect.

My aim in this writing is twofold: (1) to identify Mavratsas’s major contributions to Greek American studies and to note the potential of his work for future research; and in the interest of promoting further conversation (2) to engage with aspects of it, specifically regarding a sociologist’s responsibility vis-à-vis the worldviews of the people he studies. This angle, regarding a sociologist’s responsibility, might be seen as inappropriate, in fact misplaced, in a piece honoring this scholar posthumously. I have nevertheless decided to include it, respectfully, and with the understanding that I am discussing an early career corpus. I exercise particular caution not to critique Mavratsas from the vantage point of contemporary scholarship or paradigms he did not practice. Instead, I place my critical analysis within the theoretical axioms of the sociology that he did practice, namely Max Weber’s value-free sociology and Peter Berger’s sociology of knowledge. In other words, I identify questions that his work did not probe though they were legitimate within his working paradigm. Two reasons inform my decision for this critical evaluation: the high political stakes involved in explaining Greek American socioeconomic mobility; and Mavratsas’s own scholarly ethos. He was one of those educators who welcomed challenges and disagreements, his agonistic spirit making him popular with students.1 Unfortunately, he is not among us to enter the conversation and cherish the debate. Engaging with his work renders it visible, and promotes dialogue around his life’s work on Greek America.

There is a personal motivation, too, in my intention to initiate this reflection, one that compensates for a missed opportunity for an interpersonal exchange with Mavratsas, in the 1990s. He and I attended the same conference three times—consecutive Modern Greek Studies Association symposia—in 1995 (Harvard University), 1997 (Ken State University), and 1999 (Princeton University). In 1999, in fact, we were part of the same panel, “Ethnic Identity” (chaired by the late Adamantia Pollis), where he presented the paper “From the Production to the Consumption of Nationalist Ideology: Greek Identity in Different Contexts–Greece, Cyprus, and Greek America,” consistent with his project at the time, as I mentioned, at Princeton University. For reasons that are unclear to me, we did not seek each other out. I was a graduate student in the mid 1990s and received my PhD in 1999. I had read his work and valued it for its insights and potential, though I had strong reservations about his adherence to the Weberian notion of value-free sociology when his findings were so politically charged. This was a disagreement over the task of a scholar. Mavratsas did not see it as part of a scholar’s responsibility to critically probe his interviewee’s explanations of their upward mobility solely in terms of individual effort, while from my part I did, a concern that figured centrally in my own subsequent work.

If one of the purposes of conferences is to foster critical debate, both formally and informally, I certainly failed to engage person-to-person with a colleague whom I respected but with whom I disagreed, an oversight which, in retrospect, I very much regret. This belated engagement, well-intentioned though agonistic—necessarily so as I explained—is of course a monologue in what ideally should had been a dialogue. In defense of this one-sidedness I can only claim the purpose of this essay as a forum for a renewed social sciences exchange around the questions Mavratsas so astutely raised.

Born in Cyprus, Mavratsas received a Fulbright scholarship and studied sociology and philosophy at Boston University, where he received a BA in 1986. He subsequently pursued a PhD at the same institution, on a second Fulbright, graduating in 1993. His affiliation with the Institute for the Study of Economic Culture (ISEC), a research center, had a formative effect both on the choice of his dissertation topic, theoretical approach, and angle of analysis. The ISEC asserted the importance of investigating the role of culture (beliefs, values, predispositions) in the study of economic behavior, and, in turn, promoted empirical research to explore such linkages. Studying immigrant small businesses was a vital component of this project, and such inquiry about ethnic entrepreneurialism was undertaken comparatively, in the interest of understanding variations in the entrepreneurial orientation among various immigrant groups as well as the corresponding differentiation in rates of mobility. There was interest in the applied prospects of this research too, as identifying successful case studies could foster programs promoting self-employment in low-income communities. Success in small business initiatives carried value for economic development, and, in turn, guided research questions.

The ISEC advocated the understanding of immigrant economic culture transnationally, focusing attention both on the cultural resources that immigrants carry from their historical homelands as well as their ensuing adaptations in their host societies. The imported culture was a variable factored into the differential socioeconomic mobility among immigrants, and in certain cases could offer, in Peter Berger’s term, a “competitive cultural advantage” for one group over another.2 This approach treated ethnicity as a significant agent in a modern economy: “The road to successful adaptation and upward mobility depends precisely on not assimilating too much,” Marilyn Halter noted in her introduction to New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs (1995), a volume in which Mavratsas contributed a chapter.3

Peter Berger, a noted sociologist and the major advisor in Mavratsas’s dissertation, was instrumental in shaping the research direction of the ISEC. His “economic culture approach” interlinked the study of culture, economy, and politics. It probed the investigation of “‘the social, political, and cultural matrix’ within which economic conduct and values are embedded,” crucially shaping Mavratsas’s project.4 In what ways, the latter asked, do Greek political culture and economic values and behavior interconnect? And how do the economic values immigrants import intersect with the American economy, shaping adaptation in the host country? These questions sparked the comparison among politics, culture, and economy initially between Greek America and Greece, and later Cyprus.

Mavratsas investigated the Greek American case empirically, through a series of interviews undertaken between 1989 and 1991 in the greater Boston area. His goal was to understand a social type, the Greek immigrant entrepreneur. He worked within the Weberian tradition of ideal types. “[N]either monolithic nor static,” ideal types “point to the existence of persistently enduring empirical tendencies and sociological regularities.”5 Weber’s sociology and Berger’s sociology of knowledge anchored his practice in empirically eliciting the social actor’s subjective meanings—an individual’s knowing, valuing, and acting upon life—and then analyzing the manner by which this knowledge comes about. Mavratsas practiced “interpretive-humanistic sociology,” centering attention to how meaning informs human action, shaping, and giving rise to social realities.

The analysis of the interviews foregrounds an individual’s point of view, what an individual knows about and how he understands his reality, casting light on several important questions: Why does the typical Greek entrepreneur place work at the center of his economic and moral life? How does he—the research explicitly focused on male economic culture—understand the reasons for his socioeconomic mobility? What is meaningful in life and how is this meaning expressed? How does the immigration experience contribute toward the making of a Greek American identity, distinct from a Greek one? How does the immigrant understand American society?

Working within the research parameters of the ISEC, Mavratsas specifically set himself the task of explaining the causes for a particular socioeconomic pattern, namely the “disproportionate propensity [of Greek immigrants] for ethnic entrepreneurialism.”6 Indeed, in the locus of his empirical research, the Boston area, the percentage of self-employed immigrants from Greece was strikingly higher compared to those of several immigrant groups selected for a pilot study. According to the 1990 U.S. Census, the population from Greece was the smallest compared with populations from Cambodia, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the USSR, among other countries, numbering a total of 5,405 persons (3,085 men and 2,320 women). Yet it exhibited the highest percentage (13.9) among all in self-employment and the lowest poverty rate (10.2) within the pilot study.7 Drawing from sociological literature and reports by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Mavratsas affirmed that this regional pattern mirrored an ethnic trend at a national scale and throughout American immigration history. The entrepreneurial orientation was powerfully, yet not exclusively, present among the first wave of Greek mass immigration early in the twentieth century as well as subsequent post–World War II, and post-1965 immigration when the Hart–Celler Act enabled significant Greek immigration to the United States. “The dominant feature of this [sociological] entity,” Mavratsas asserts, “is a disproportionate propensity for ethnic entrepreneurialism, a phenomenon that is, and always has been a fundamental element of Greek-American life.”8

At the time of his project, sociologists of Greek America had identified and situated this pattern as a manifestation of a particular immigrant adaptation, that of the entrepreneurial middleman minority, a socioeconomic class, that is, of small businessmen—restaurateurs, grocers, confectioners, shoeshine and shoe repair parlors, florists, and theater owners—who mediated the flow of goods between consumers and producers. Holding a middle-rank class position between wage earners and the bourgeoisie, small business owners develop a petit bourgeoisie culture stressing the family’s economic well-being as well as expressing a socially and politically conservative outlook. The “consistent overrepresentation in ethnic entrepreneurialism” makes the Greeks “one of the paradigmatic cases of middleman adjustment in American society,” while the dramatic transition from small businessmen to professionals within a single generation calls for explanation.9 As sociologist Kourvetaris notes, the American-born second generation did not, “as a rule, follow these middleman minority enterprises. It entered white-collar, professional and semi-professional, and managerial-type occupations.”10 This pattern pointed to an exceptional case: The “overriding trend,” Charles Moskos wrote, “has been that of a social ascent with few parallels in American history.”11

A set of questions follows from this: how to explain the phenomenon of rural peasants rapidly turning into the petit bourgeois, and their offspring into white collar professionals? Sociologists have offered insights, pointing to the immigrants’ previous market skills in Greece and their work ethic as causes for the immigrant transition. Parallels were drawn between the Greek immigrant and the Calvinist work ethic.12 But no comprehensive theoretical model was developed to explain the interrelationship between (1) the adaptation of former peasant Greek immigrants to small business owners; (2) the resulting formation of a distinct Greek American identity and its associated differentiation from a Greek identity; and (3) the occupational transformation across generations from immigrant entrepreneurs to white collar professionals.

Mavratsas engaged with these links empirically, collecting life histories among Greek male immigrants who made a living as restaurant owners, an industry with a heavy concentration of Greek immigrants as owners and employers, in fact “the most successful ethnic group in this type of business.”13 He focused his attention on a constellation of cultural resources they imported from mainland Greece, calling it “transplanted cultural endowment,” which he saw as contributing toward their entrepreneurial orientation and enabling relative mobility.14 It was a web of interrelated values, experiences, and predispositions—family honor, “individualistic nuclear familism that promotes the mobility and differentiation of its members,” an urban and commercial orientation, independence, and the associated proclivity for self-employment, as well as the ingrained belief in the prospect of socioeconomic mobility—that made ethnic entrepreneurialism, he argued, “the culturally preferred occupational option of Greek immigrants.”15

Following Weber, Mavratsas saw these “psychological premiums” as a manifestation of a protomodern economic culture, different from both traditional subsistence economies in which extended kin networks stress in-group loyalty stifling an individual’s entrepreneurial initiatives and from modern economic culture in which formalistic, impersonal principles guide the rational motivation to maximize economic returns. In contrast to the rational formalism of the latter, the immigrant protomodern economic ethos insisted in maintaining family-centered, interpersonally oriented entrepreneurs, even when this meant refraining from the formal rationality of maximizing profit via business partnerships. In contrast to the former, the immigrant individualistic nuclear familism “does not hinder the individuation and mobility of its members,”16 while southern Italian familism, following the work of Herbert Gans, exercised pressures among all members of the extended family for “familial solidarity and ‘ingroup loyalty and conformity to established standards of personal behavior’ rather than individual mobility and advancement to the middle class.” Furthermore, largely practicing subsistence agriculture, southern Italian immigrants “did not possess the commercial skills and orientations” of Greek peasants.17 This traditionalism “stifled the educational and socioeconomic advancement of individuals.”18

Mavratsas injected Greek American sociology with theoretical rigor, reflecting on his epistemology, being explicit about his methodological assumptions and limitations, and, ultimately, proposing a powerful explanatory schema. The broad contours of his model are as follows: under immense pressure to make it economically—the primary motivation for emigrating in the first place—immigrants mobilized their transplanted cultural endowment, which proved adaptive to the context of American capitalism. The decision to achieve faster mobility by way of self-employment, preferred over wage labor, was facilitated by available ethnic and kinship networks already practicing entrepreneurialism and offering opportunities for apprenticeship. The middleman minority adaptation crucially shaped their petit bourgeois cultural and political outlook, which, in turn, contributed toward a distinct Greek American identity, a hybrid identity, neither totally Greek nor wholly American.

The major insight in this formulation is the “strong family resemblance” that Mavratsas proposes between the Greek immigrants’ economic ethos and that of the pioneer capitalists as formulated in Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The commonality for both is the “ethical sublimation of practical rationality.”19 For small business Greek immigrant owners, attaching a moral purpose to work intrinsically connected with family honor, the moral obligation to advance the interests of the family unity, sacrificing the self if necessary for the advancement of the children (αποκατάσταση των παιδιών):

In both groups, life is centered around homo oeconomicus and has a rather ascetic and puritanical character. This lifestyle, moreover, is in both cases very favorable to the development of small independent businesses and comparatively high rates of socioeconomic mobility. In both economic cultures, economic life is seen as essentially tied to value-rational considerations; with the Calvinist it was the arena in which one proves one’s election and ensures one’s salvation, while for the Greek immigrant it is in the arena in which one maintains one’s honor by being an able provider for one’s family.20

Mavratsas built on this value-centered rationality to identify and explain the formation of a sui generis Greek American immigrant identity. Unlike in Greece, he noted, the immigrant lacks the option of entering into clientelist relations with the State, a condition that directs him to “pursue the welfare of his family exclusively through economic,” not political means.21 Coupled with the moral imperative of success and his social marginalization, the immigrant entrepreneur, as a social and economic type, cultivates an intense work ethic, his “role as an economic actor acquir[ing] increasing importance in the development of his identity and self-understanding. It becomes the paramount mode of his existence.”22 This “economic intensification,” as Mavratsas calls it, parallels a process of puritanization, the development that is of a world view defined by social and political conservatism; an ethos “suspicious of both social democratic ideals and working-class orientation,”23 and “non-sympathetic to the interventionist state”;24 adherence to family and church life; and an orientation marked with “a more ascetic life-style with less emphasis on literary and artistic pursuits,”25 coupled with a “certain anti-intellectualism,” and aversion to bohemian lifestyles.26 This experience gives rise to a hybrid culture, Mavratsas suggests, combining the immigrant petit bourgeois culture with American belief in opportunity and prioritizing individual responsibility as the means for mobility. Embodying this ethos, the immigrants “think of and understand themselves primarily in contrast and comparison to mainland Greeks.”27 He differentiates himself from the political culture of clientelism in Greece, seeing himself as “a better worker” (καλύτερος δουλευτής), who keeps a safe distance from the overpoliticization and hedonism of Greek culture. An interviewee marked a strong boundary between himself, a Greek American, and Greeks: he “really detest[s] the Greeks” particularly when he visits the country.28 The conditions of migration and personal experience validate this taken-for-granted knowledge.

Mavratsas’s sociology works with Weberian ideal types. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the findings are presented through the point of view of a fictitious male persona, Costas, whom Mavratsas constructs on the basis of the sum total of his interviews to represent a typical immigrant who turned into a relatively successful restauranteur. A poor farmer in southern Greece who immigrated in 1965, and joined his maternal uncle, this figure had little formal education. He did not mind working menial and “undignified” jobs, lived a frugal life, and saw the pizza business as the most practical route to mobility, a business about which he learned through a two-year apprenticeship in the business of a coethnic. Costas valued his business as an enterprise on which he exercised direct control, allowing an independence from outsiders whom he deeply distrusted, and offered opportunities for interpersonal interaction with customers and employees. His ethos contrasted with the “formal rationality” that frames work in an “impersonal and formalistic manner”29 to opt for a “personalistic-familistic” character, the norm among Greek American small businessmen. Costas took pride in his “managerial and entrepreneurial spirit,”30 and in his sacrificing for his children, fulfilling his moral obligation as a good provider—being in a position to finance a college education for all his three children, including the eldest whom he dissuaded from studying psychology to study law at a “very expensive” private university. His daughter “agreed to attend college only when her father promised her a nice new car at the end of her sophomore year.”31 Church, family, and his business constitute the center of his life. He has “developed a Greek-American identity,” “he is not simply Greek nor totally American.” He attributes Greece’s problems to “people there … not willing to work hard,” and “votes Republican because he hates to see taxes being spent on social welfare.” This character self-identifies as a conservative who believes that there is equal opportunity for everyone in America. “Only those who do not have the drive, stay behind. ‘Δουλεύουμε εμείς για να τρώνε άλλοι,’ do we work for the others to eat?” he maintains.32 From his vantage point, poverty or homelessness is a phenomenon largely because of individual unwillingness to work. This is the knowledge that Costas brought to his understanding of American society.

This figure, then, represents a type within a pattern, the petit bourgeois ethos of Greek immigrant entrepreneurs whose family orientation, work ethic, and conservatism are elevated and placed at the heart of his existence, attaching meaning to his life. He sublimates work, since “financial success becomes an ethical imperative,” associated with an “ascetic life-style in an almost heroic mode.” It is part of the struggle, “a manifestation of the agonistic spirit and toughness necessary for succeeding in life.”33 The petit-bourgeois ethnic entrepreneur develops a strong sense of individual responsibility, directing his resources toward family and the preservation of ethnic community.

Mavratsas repeatedly reminded his readers that Greek America is not a monolithic entity. Working with social types he focused on a powerful pattern, the professional trajectory from peasant into petit bourgeois entrepreneur and eventually the middle-class white collar professional. This has been a trajectory described by Charles Moskos as embourgeoisement, a broad and problematic term,34 and a process of mobility that finds statistical validation in the oft-quoted census fact of Greek Americans being the highest educated American ethnic group and the second highest in economic attainment. The lack of specificity in the term served Mavratsas’s typological orientation well. It fit with linking the cultural capital of family honor—sacrificing parents for the mobility of the children—and “competitive individualistic familism,”—the simultaneous, agonistic coexistence between intense familism and intense individualism—promoting the socioeconomic advancement of the offspring through college education.35 It is this pattern, Mavratsas argued, that captured the increasing modernization of Greek America, from the personalistic rationality of the immigrant entrepreneur to the logical formality of the American-born professional.

Accepting Greek American embourgeoisement as a key analytical category inevitably directed Mavratsas toward what in Greek American historiography is known as the “Moskos–Georgakas debate.”36 The disagreement between labor historian Dan Georgakas and sociologist Charles Moskos was about the extent to which the Greek American working class and various leftist expressions within it have shaped the ethnic community and national life. Georgakas put forth the case of Greek American historiography not properly acknowledging this impact, while Moskos maintained in response the negligibility of the impact. Mavratsas cited the pattern emerging from his empirical findings—“[t]he community that emerged out of this study’s data has a very strong middle-class identification and is extremely suspicious of and hostile toward working-class orientation and values”37—to unequivocally take a side:

One finds the occasional union activist and professed communist, but the clear tendency is for affiliation with the middle class and a deeply conservative ethos. The Georgakas claim misses the actor’s point of view and “contrasts with the conventional perspective Greek Americans have of themselves and their history” (Moskos 1982: 55). … I strongly disagree with Kitroeff’s (1987: 73) verdict that the “jury is still out … for lack of evidence.” The empirical record of this dissertation undeniably shows that in the Moskos-Georgakas disagreement, Moskos is the clear winner.38

Unequivocally, Mavratsas declared universal validity to his specific ethnographic case.39 Though his claim may apply to his occupational and regional sample, there is no clear indication that his research probed the perspectives of those immigrants subsisting under the poverty level, nor those of students, professionals, and those who may have reasons to be hiding leftist sympathies. Seen from today’s perspective, the answer to the debate is not as clear cut. The current national and ethnic importance assigned to Greek American labor organizer Louis Tikas, murdered during the infamous labor strike at Ludlow, Colorado, in 1914, cautions against readily dismissing the contemporary value of working class activism in the past. Research on the question must cast its net wider and deeper within the archive but also acknowledge regional specificities in its design. Greek Americans in the states of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico, for instance, have radically different collective and family histories, memories, and experiences than post-1960s immigrant entrepreneurs.

For the ISEC, ethnic entrepreneurship did not merely demonstrate the importance of ethnicity for immigrant adaptation. It also offered evidence for its significance for the nation. The crux of the matter was not only immigrants retaining ethnicity but also embracing, embodying, and ultimately reproducing national values. Understanding the ethnic entrepreneur meant to not only recognize the importance of immigrants as “an enormous resource for the vitality of U.S. society and the U.S. economy”40 but also to recognize the resonance of this figure as an American folk hero. As Halter noted, advocating the institute’s support of the subfield of ethnic enterprise studies, “an unlikely consensus evolved among scholars on the right, left, and center that entrepreneurship would simply become obsolete in advanced economies.” Yes, she continues:

the entrepreneurial spirit has shown itself to be surprisingly resilient in a postindustrial economy, particularly in the case of ethnic-based enterprises. The small business owner as folk hero in American culture endures.41

True. Greek diners, for instance, a ubiquitous phenomenon in the American landscape, are routinely portrayed in mainstream and local media as products of immigrant work ethic and frugality, serving as “quintessential small-town hangout[s],” meshing immigrant grit, American opportunity, and social everydayness.42

But one needs an additional layer of analysis in the valuation of the immigrant entrepreneur as American folk hero. What is left unsaid in Halter’s exposition above is that the iconic place of the ethnic entrepreneur in the national mythology has been appropriated by conservative populism, shaping public perceptions about not only the identity of immigrant business owners, but also the identity of American society. The upward mobility of immigrants, especially those from Europe, has been central in debates about opportunity, discrimination, institutional racism, democratic values, and welfare. It follows that ethnic entrepreneurship is not merely a question of imported immigrant culture intersecting with economic behavior, but also of national culture serving political interests. In the context of post–Civil Rights struggles over the society’s responsibility vis-a-vis historically discriminated groups, the ethnic entrepreneur’s staunch advocacy of bootstrap mobility has been at the thick of cultural politics. The encounter between the immigrant newcomer and the free market has been intrinsically connected with the cultural and state politics of multiculturalism, particularly as it played out in relation to group rights and ultimately the argument for a “color blind” society. As I have noted elsewhere:

The nation, which previously opened up to include European Americans, was now extending a welcome mat to admittedly disenfranchised minorities. The legal barriers to ethnic equality had collapsed: Now needed were racial minorities performing the very ethos that propelled white ethnics to successful assimilation and to reaping its rewards. Hard work, discipline, deferment of gratification, and willingness to subdue collective ethnic interest to national interest were key to racial (seen as ethnic) success. This “myth of ethnic success” (Steinberg 1981, 82) organized the Eurocentric model of “immigrant analogy.” If the Polish Americans and Greek Americans have made it, the narrative never tired of repeating, there should be no reason that in a liberal state others could not as well—unless, of course, it was their fault. The white ethnic advancement through the pulling up by the proverbial bootstraps served as the core ideology of individual meritocracy. Nathan Glazer (1973) asserted, “Only the individual has rights, not the group”; institutions “must be open to all, color blind, and indifferent to group affiliation or group origin” (175). In turn, the narrative of a heroic overcoming of hardship in the past through toil and perseverance links European Americans together into uniform whiteness and interethnic solidarity.43

Bringing together culture, economy, and politics, the encounter between European immigrants and the American society entails precisely the constellation of relations that were at the center of Mavratsas’s research project.

It was unlikely that Mavratsas would not come across statements of Greek American ethnocentrism. Indeed, he did dutifully record and report a recurrent view among his interviewees: “‘Greekness” … [as] a feeling of superiority,” a position he recognized as a pervasive and “permanent feature of Greek-American ‘mythology’ and of the Greek-American understanding of ethnicity.” “This ‘success story,’ … is a significant part of the Greek-American ethos,” he wrote, Greek Americans being “more than willing to ‘explain’ their ‘success story’ as evidence of purely ethnic superiority and even destiny.”44

Troubled by the ethnic hierarchies that ethnocentrism generates, Mavratsas explicitly opposed it, albeit in a footnote. This placement indicates perhaps an ambivalence as to whether such a critique fit his core analysis, notably feeling it was necessary to reiterate in this context “the value-free character of [his] analysis. Still he was unequivocal. Higher rates of socioeconomic success of a group do not translate into corresponding ethnic superiority, he pleaded, advocating for a broader appreciation of groups’ accomplishments. Those lacking socioeconomic distinction may be experiencing success in other areas of social life. Mavratsas was forthright: it is “a sign of bigotry and parochialism,” he asserted, to posit economic success as evidence of the superior nature of some and the inferior “moral” or “ontological” worth of others.45 But his intervention was consistent with Weberian sociology. As Alvin Gouldner observes:

If Weber insisted on the need to maintain scientific objectivity, he also warned that this was altogether different from moral indifference. Not only was the cautious expression of value judgments deemed permissible by Weber but, he emphasized, these were positively mandatory under certain circumstances.46

In reflecting on whether Greece and Cyprus should undertake steps toward economic and political modernization, Mavratsas asserted that it is not the sociologist’s task to take a position on this dilemma. “Value-free social science,” he wrote, “cannot judge this decision.”47 He was unequivocal, however, in proclaiming the sociologist’s responsibility to analyze the consequences of this decision. It is within the domain of value-free sociology then to examine the social and political implications of a people’s understanding of and acting upon social reality. Still, Mavratsas opted to remain neutral when it came to the immigrants’ bootstrap explanation of success as the sole outcome of entrepreneurial acumen (σπιρτάδα), hard work, and individual responsibility. He probed neither the sources of this perspective, its connection with larger political discourses nor its political implications. This reticence, one notes, was contrary to his understanding of the scope of sociological analysis he so clearly articulated, an exposition worth quoting in full:

Whereas the sociologist must begin with the subjective meanings of acting individuals, and his concepts must be faithful to the first-order categories of the social actors under investigation, he must also aim at “causal adequacy” which is an intellectual task that may indeed transcend the specific understandings of concrete human beings, especially when what is studied involves large scale historical and/or comparative considerations. That social reality is constituted in and through the actor’s point of view, which, …, provides the only empirically available subject matter for sociological analysis, does not mean that the actor is always a knowledgeable sociological theorist.48

This programmatic position illuminates the degree to which Mavratsas’s sociology is anchored in Berger’s sociology of knowledge. Whereas the “man in the street” takes his knowledge about reality for granted, Berger wrote in his 1966 seminal book, the sociologist must inquire about the ways by “which any body of ‘knowledge’ comes to be socially established as ‘reality’”:

the sociology of knowledge must concern itself with whatever passes for ‘knowledge’ in a society, regardless of the ultimate validity or invalidity (by whatever criteria) of such ‘knowledge.’ And insofar as all human ‘knowledge’ is developed, transmitted and maintained in social situations, the sociology of knowledge must seek to understand the processes by which this is done in such a way that a taken-for-granted ‘reality’ congeals for the man in the street. In other words, we content that the sociology of knowledge is concerned with the analysis of the social construction of reality.49

When it comes to the relations between immigrant cultural endowment and ethnic entrepreneurship, Mavratsas’s analysis represents a textbook example in the sociological understanding of the petit bourgeois construction of reality. But when it comes to the immigrants’ knowledge of American society, his analysis neglects to probe a guiding principle in practicing sociology of knowledge, namely the concern with “the relationship between human thought and the social context within which it arises.”50 Though aptly placing immigrants in their Greek context, his work neglects to place the immigrants within an all-important American political context that circulated widely and validated decisively the bootstrap version of upward mobility. It bracketed off the operation of formal and informal structures working in favor of European immigrants—classified as white ethnics at the time—while hindering labor market opportunities among people of color.

Understandably, Mavratsas produced his work at a moment prior to the wide circulation of whiteness studies, an academic field that brought sharper analytical attention to how the racial positioning of individuals, including immigrants, within the social structure affects social and economic experience. In the context of his study, then, the question presented itself: did Greek immigrants possess a competitive racial advantage vis-à-vis people of color in the economic landscape, racially charged as we will see, of the wider Boston region? In the American south, where the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow legally ended only in 1964, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, white ethnics unequivocally possessed a racial privilege over African Americans—treated as second class citizens—a fact that points to region as an important analytical category in ethnic entrepreneurial studies. But in Boston? A book chapter in New Migrants in the Marketplace, the same book where Mavratsas published his findings, provided empirical evidence to register the operation of racism against immigrants from the West Indies within the regional labor market.51 It follows that the folk statements positing hard work as the sole route to mobility, and in turn generating feelings of ethnic superiority, were missing the impact of racism on differential mobility.

Mavratsas was aware of the power of sociological work to shape self-understandings of ethnicity. Two-thirds of his interviewees, he was “quite amazed” to discover, were “well informed about Moskos’s Greek Americans,”52 a book underwriting the idea of self-propelled “struggle and success,” in tandem with it being “a dominant feature of the Greek-American ethos and identity.”53 In this particular conjuncture between scholarship and a people’s subjective meanings, the authority of sociology encountered the authority of personal experience, the former validating and reinforcing the latter, leaving a direct outcome of this self-understanding unscathed, namely Greek immigrant ethnocentrism. The self-representations of “struggle and success” as identity furnished the entrepreneurs “evidence of purely ethnic superiority.”54

There was something larger at stake in the intersection between scholarship and folk knowledge. They were both contributing in tandem to a particular way of becoming American: assimilating into understanding American society and history as a pattern of inclusion, a notion that was much in vogue both in a thread in academic writings, public policy, and the wider society in the 1960s and beyond.55 In bracketing off the question of unequal structures of opportunity, which disadvantaged racialized minorities, to embrace instead a culturalist explanation of mobility, both sociology and Greek Americans were validating “the ‘dominant American ideology’ of individual opportunity and success.”56 Writing in 1989, sociologist George Kourvetaris outlined how the “struggle and success” ideology represents assimilation into a particular American ideology of class structure:

Along with many other ethnic Americans, Greek Americans have accepted … the “dominant stratification ideology.” This ideology is also called the “logic of opportunity syllogism.” … It provides a deductive argument that justifies inequality of economic outcomes in the American stratification system. The basic assumption in the “opportunity or dominant” economic hypothesis is that opportunity for economic advancement is based on hard work, and that this opportunity is plentiful. From this premise, two deductions follow:

(1) Individuals (not society) are responsible for their economic fate. This is also in accordance with economic entrepreneurial or classical laissez-faire economic liberalism in that individual economic outcomes are directly proportional to individual inputs (talent and effort). From this follows a

(2) Second deduction, namely that the resulting unequal distribution of economic rewards in American society is, in the aggregate, equitable and fair.57

The ethnic entrepreneur turns into a national folk hero precisely because this figure encapsulates an idea entrenched in American political life, that of self-reliance, individualism, and hard work, and, in doing so, deflects attention from structures of oppression. This bootstrap model became a politically inflected narrative in the post-civil rights “culture wars” over the nature of American multiculturalism. Since the early 1960s, if not earlier, conservative renderings, highly visible at the academic, intellectual and party politics level, elevated “the immigrant success story” as the prototype of ‘the American experience,’” the “bootstrap self-help” serving as evidence of “the impropriety of state intervention in correcting for the injustices of racial stratification.” European immigrants were posited as “the exemplars of this ‘central tendency in American history’–its openness, [and] its premium on a diversity of participants.”58 Not surprisingly, the ideal social type in Mavratsas’s study votes republican and staunchly opposes welfare.

In reflecting on the social construction of reality, Mavratsas aptly noted that human subjects are neither isolated entities, nor, as I mentioned, always knowledgeable sociological theorists. They are being shaped by their surrounding milieu, and not always in a position to make correlations among realities not immediately connected with their own personal experience.59 It is the responsibility of the sociologist, according to the sociology of knowledge, to correlate concepts and connect subjective meaning with wider social phenomena. An ethnographic fact that Mavratsas reported, albeit in a footnote, provides a point of departure for reflecting on the task of sociology as he saw it.

Many of the earlier immigrants that I interviewed … said that they used to be more pro-welfare, pro-liberal, in short less conservative, when they first came to America, but that their experience with American society and politics taught them that such liberal policies tend to be abused, usually at the expense of the tax payer.60

Such ethnographic evidence underlines a political transition, a trend toward conservativism. How does one make sense of this reorientation? The immigrants cite experience-based knowledge to justify it, an understanding that the sociologist registers and describes as a social fact. To recall Peter Berger, however, the sociology of knowledge requires analysis of the social processes through which “a taken-for-granted ‘reality’ congeals for the man in the street.” To build on this mandate I turn to Matthew Frye Jacobson who demonstrates the powerful resonance in the 1980s between “street sensibilities” among white ethnics, the scholarship of immigrant bootstrap, and the discourse of the Republican party. The power of populist conservatism, ubiquitous at the time in academic, media, and popular writings, cannot be absent from investigating the major political shifts occurring among white ethnics, including Boston in the Northeast. As Jacobson notes, Black struggles for equality, recognition of and reparation for past injustices directed “disgruntled white ethnics, largely of the Northeast and Midwest,” toward the Republican party. They “joined Nixon’s ‘silent majority’ in 1968” and “became known as “Reagan Democrats in the 1980s.”61 Notably, the appeal of “the segregationist George Wallace ‘to ethnic voters in the urban Northeast’”62 cannot be understood independently from people of color interrogating the state as responsible for historical patterns of injustices and demanding structural changes. It is this larger, racially charged political landscape, that helps us understand the resonance between the conservative argument and “street-level discussion among white ethnics.”63 White ethnics were turning toward conservatism not necessarily because of “minorities’” alleged abuse of welfare but because conservative ideology served white ethnic interests. As anthropologist Karen Brodkin notes, the stigmatization of African Americans and immigrants from Central America “as lazy welfare cheats encourage[s] feelings of white entitlement to middle-class privilege.”64 Far from being a neutral ethnographic fact, immigrant conservatism was steeped in powerful discourses safeguarding self-serving social and economic privileges within a system of racialized hierarchies. Immigrant knowledge was mediated by the ideology of the corrupt, not deserving, minority poor. It was culture, not structure, that determined adaptation. While Greek immigrant culture offered a transnational asset, Mexican and African American culture worked as liability, being the leading cause for poverty among the latter according to the infamous 1959 “culture of poverty” thesis.65 The Greek entrepreneur assimilated into an enduring national ideology, one shifting attention from considering the constitute role of socioeconomic conditions on lack of mobility, instead blaming the poor themselves.

The Greek American sociology of struggle and success did not venture into naming the interconnections between subjective views, racial politics, and political discourses, neglecting to attend to the political implications of the bootstrap ideology. It refrained from reframing folk understandings of success by excluding from serious consideration the all-important racialized political economy of labor, leaving the bootstrap model, and the ethnocentrism embedded to it, unscathed. It was not interested in offering an alternative, empirically oriented, understanding of Greek mobility, and so missed the opportunity to raise consciousness among Greek Americans about the fundamental differences between the histories of immigrants from Europe and those of people of color. In hindsight, the reticence to posit the authority of professional sociology to question the folk model of mobility did not interfere at least in curbing the pervasive reproduction of the bootstrap narrative among the American-born generation, in full swing today.66

Graduate students are shaped, consciously and unconsciously, by the work of their advisors as dissertations are produced in contexts where PhD candidates navigate power relations within the academy. Few students, if any, can claim absolute autonomy when it comes to their place within this web of unequal relations. It will be unfair therefore to critique any early career work for being shaped by the intellectual presence of the principal supervisor. I would like to register here a particular commonality between Peter Berger, the mentor, and Caesar Mavratsas, the budding scholar, namely the importance they both assigned to strong civil society. This is not to suggest, however, that they arrived to this valuation via identical intellectual and political routes. In fact, Berger advocated civil society as a mechanism of resource redistribution in American society, while Mavratsas discussed its relative importance as a function of political and economic culture, in the comparative context of Greece, Cyprus, and Greek America.

In a 1977 writing, reprinted in a volume bringing together the so-called neoconservative thinking on several topics ranging from capitalism to the welfare state, and minorities to campus politics, Berger fleetingly registered the importance of the welfare state, an issue central to neoconservative thinking, opting to focus, instead, on alternative mechanisms contributing welfare services.67 As Jacobson notes, Berger invested value in the “the four staples” of the European immigrant narrative–“the neighborhood, the family, the church, and the voluntary association”68–as institutional “mediating structures” providing social cohesion and desirable sources of morality, meaningful relations, mutual help, and alleviation of poverty. These were values at the center of Berger’s public policy piece and his proposals to enhance these traditional structures in American society.69 True to the neoconservative impulse, the emphasis was in empowering the values, mores, and “settled convictions of the average American,” for whom those “who wear this clothing [neoconservatives] … have great sympathy and often take their cues from.”70 Ethnic communities were a vital component of the social universe of voluntary associations that grounded each of the various and diverse communities of Americans to place, morality, and meaningful associations. The affinities between Berger’s policy recommendation and the various narratives celebrating European immigrants as exemplars of American multiculturalism have been admirably explored by Matthew Frye Jacobson. The main point I extract from his rich exposition is the political utility of Berger’s mediating structures for the Republican party, which embraced the concept of civil society as a safety mechanism that minimizes government allocation of welfare resources. “This is America,” “George Bush declared at his party’s 1988 Convention. “[T]he Knights of Columbus, the Grange, Hadassah, the Disabled American veterans, the Order of Ahepa, the Business and Professional Women of America …–a brilliant diversity spread like stars, like a thousand points of light in a broad and peaceful sky.”71

The trajectory of a scholar bracketing off direct engagement with the specific workings of state welfare to instead valuate community institutions is also evident in Mavratsas’s analysis, which also focused on the moral preferences of the average ethnic entrepreneur/citizen—family, community, and church—and their political aversion to the welfare state. Mavratsas recognized the importance of family, ethnic community, and religion as meaningful centers in the life of the ethnic entrepreneur. There seems to be a hint of admiration in his rendering of Greek America as “a civil society par excellence.”72 But his angle is different than Berger’s, which advocated an ideological position in the contested issue of social cohesion, national morality, and distribution of resources. In contrast, Mavratsas was pursuing a comparative scholarly analysis of the linkages among civil society and economic and political culture. He argued that the clientelist state leads to the overpoliticization of society at the expense of civil society, a conclusion worth quoting in full:

[A] striking difference between Greek America on the one hand, and Greece and Cyprus on the other, is that in the former, politics has a significantly lesser role. This is not to deny, however, that often the political passions of Greece are transplanted in Greek America, dividing the community into hostile factions and posing serious obstacles to its institutional development. But even in such cases, politics remains a marginal phenomenon in that it is never a mechanism for gaining access to a state apparatus and the benefits that come with it. Political conflicts among Greek-Americans are usually about cultural issues, such as identity, language and religion, and not about raw power. Given this aspect of the ethnic or communal politics of Greek America, the political sphere acquires what we may call an autonomy and it does not interfere with the economic development of the community.73

Unfortunately, the linkages that Greek Americans drew between their community institutions and the national ideology of self-help remained outside the purview of his work.

Mavratsas’s contributions have been multiple. Within a single dissertation, he advanced Greek American studies in several fronts, including (1) transnational scholarship; (2) comparative ethnic studies—primarily comparative work between Greek America and Greece; and (3) theoretically informed analysis, all pioneering scholarly contributions. What’s more is that he illustrated ethnicity as social production, a process of identification that takes place at various intersections of cultural values, class, and gender within specific contexts in the host society. Ethnic identity in this formulation is a dynamic process entailing negotiation, adaptation, transformation, and differentiation. Sociologists speak about this process as ethnogenesis, a notion which aptly moves away from the conventional view of ethnicity as loss or attenuation of cultural traits (language, behaviors and values) moving instead toward the understanding of ethnicity as a social process in-the-making: the production of new identities and cultural arrangements (syncretic, assemblages, reconfigurations) within concrete sociopolitical contexts. The analytical power of approaching ethnic identity as social production lies in its capacity to explain internal heterogeneity within a particular ethnic group as various identities (class, gender, cultural, sexual) negotiate the same environment differently, and individuals sharing similar subject positions negotiate different environments (rural vs. urban, regional vs. national) differently.

What is the value of Greek American studies? This is an issue that academics working on immigration and ethnicity are prone to raise, often in a questioning mode. Mavratsas’s work offers a productive answer. His focus on the particularities of the Greek immigrant adaptation necessitated a transnational framework of analysis, establishing the necessity of understanding Greek immigrants both in relation to the “cultural endowment” of their historical homeland and their specific adaptations in the host society. Both contexts must be considered in relation to each other. This framing implicitly legitimizes the academic value of Greek American studies. Ethnic studies in the United Stated has had already established the necessity for a culturally specific examination of immigrant peasants. As early as 1964, for instance, Rudolf Vecoli, writing as an Italian American studies scholar, made the case that Italian immigrants “could not be understood through a general study of the European immigration,” thus confronting Oscar Handlin’s homogenizing and widely held notion of a universal “European peasant village.”74 Ethnographic comparative studies across European immigrants and ethnicities present the next promising research frontier.

Since the mid-1990s, Greek American sociology and ethnography have been largely impoverished academic fields, the few bright scholarly exceptions illuminating the dramatic dearth of a wide, in-depth and sophisticated corpus. In the case of Mavratsas, Greek American studies lost an exceptionally promising early career scholar. Unfortunately, as I mentioned, no Greek Americanist has engaged with the scholarship he bequeathed us, particularly his comparative work, and his bringing the political, the economic, and the cultural into conversation.

Will there be interest toward this direction? Given the few active scholars in the field a pragmatic answer could range from dejected pessimism to the agnosticism of “there is no way to tell.” While Greek American studies keeps losing exceptional junior scholars to other fields, it is gaining, often unexpectedly, through the infusion of new scholarly talent. There is the guarded possibility that perhaps a new generation or established scholars in sociology, cultural anthropology, and political science might be building on Mavratsas’s work, developing it in various directions.

Mavratsas was aware that working with the notion of the ideal type circumscribes one’s work. In fact, it has no merit after the work of Alfred Schutz, after Chicago School of Sociology, after Symbolic Interactionism and after Ethnomethodology. The category “typical ethnic entrepreneur” is limited and limiting. Obviously, it is not raising questions neither about failed entrepreneurs nor immigrant working class poverty. It is not probing diversity of world views within small business owners. It is not concerned about women’s views or intrafamily negotiations, even conflict, about what constitutes success in life. It is not addressing the phenomenon of nuclear families entering business with kin, a situation not disconnected with family fallouts and failures. It is not in a position to account for those cases where an entrepreneur did not sublimate work, displaying no sacrifice for the offspring.

What is more, while the transmission of the petit bourgeois view of bootstrap mobility has been powerfully reproduced by the American born-middle class, both at the level of the ethnic community and at a national scale, there is also the question of agency among those Greek Americans who have been confronting their parents’ conservatism. It has also been noted that the embourgeoisement framework does not acknowledge the fact that several white collar professionals such as educators are experiencing relative downward mobility compared to that of their immigrant parents and grandparents.75 It is up to the sociologists and ethnographers of the future to explore the diversity, contradictions, and variations of Greek America, and in doing so expand the understanding of small business owners and the “second generation” beyond typologies. Such a development, I believe, would have been gratifying to Mavratsas, aligned with his investment to advance Greek American sociology.

Yiorgos Anagnostou is a professor of transnational Modern Greek Studies at The Ohio State University. For his research profile see, https://www.mgsa.org/faculty/anagnost.html

Notes

I thank Dušan Bjelić, Vangelis Calotychos, and Despina Lalaki for their useful insights.

1. Obituary, University of Cyprus Professor Caesar Mavratsas, CyprusMail Online, October 6, 2017. https://cyprus-mail.com/2017/10/06/obituary-university-cyprus-professor-caesar-mavratsas/

2. Caesar Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture: The Intensification of Economic Life and a Parallel Process of Puritanization,” in New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, ed. Marilyn Halter (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995), 117, fn.3.

3. Marilyn Halter, “Introduction–Boston’s Immigrants Revisited: The Economic Culture of Ethnic Enterprise,” in New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, ed. Marilyn Halter (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995).

4. Caesar V. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America: Comparative Issues in Rationalization, Embourgeoisement, and the Modernization of Consciousness,” Modern Greek Studies Yearbook 10/11 (1994/1995): 141.

5. Ibid., 143.

6. Caesar V. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement. The Formation and Intergenerational Evolution of Greek-American Economic Culture (PhD diss., Boston University, 1993), 98.

7. Halter, 5.

8. Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture,” 98.

9. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 97.

10. Yorgos Kourvetaris, “Greek American Professionals and Entrepreneurs,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, Special Quadruple Issue, The Greek American Experience XVI, nos. 1–4 (1989): 109.

11. Charles C. Moskos, Greek Americans: Struggle and Success, 2nd ed. (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1989), 139.

12. George Christakis, for instance, in an unpublished lecture (Chicago, Illinois, 1988). In Kourvetaris, 112.

13. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 210.

14. Ibid., 2.

15. Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture,” 98–99.

16. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 142.

17. Ibid., 104.

18. Ibid., 325.

19. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 160.

20. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 250.

21. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 159.

22. Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture,” 106.

23. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 151–52.

24. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 110.

25. Ibid., 108.

26. Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture,” 113.

27. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 98.

28. Ibid., 453, fn18.

29. Mavratsas, “Greek-American Economic Culture,” 103.

30. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 274.

31. Ibid., 281.

32. Ibid., 283, 284.

33. Ibid., 103, 101.

34. Dan Georgakas, “Response to Charles C. Moskos,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora XIV, nos. 1&2 (Spring–Summer 1987).

35. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 144.

36. Alexander Kitroeff, “The Moskos–Georgakas Debate: A Rejoinder,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora XIV nos. 1&2 (Spring–Summer 1987).

37. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 311.

38. Ibid., 311–12.

39. Mavratsas noted that in Massachusetts, the “overwhelming majority of Greek Americans with electoral positions belong to the liberal faction of the Democratic Party,” a fact that he saw as a paradox given the “conservative milieu from which they originate.” It was not ideology that steered the aspiring politicians, he proposed, but a decision “reflecting the adaptability and pragmatic qualities of the Greek-American ethos.” With no “Greek American voting block” in the state, American-born politicians gravitate toward the Democratic party because of its regional dominance, which maximizes their “chances of [political] success.” But contrary to the tenets of humanistic sociology, Mavratsas did not seek the subjective meanings these politicians attached to their profession. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 329–31.

40. Berger Peter, “Foreword,” in New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, ed. Marilyn Halter (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995), viii.

41. Halter, 1–2.

42. “N.J.’s Best Diner: Why Are There So Many Greek-Owned Diners?” Nov. 29, 2015. nj.com. https://www.nj.com/jerseysbest/2015/11/njs_best_diner_why_are_there_are_so_many_greek-own.html)

43. Yiorgos Anagnostou, “White Ethnicity: A Reappraisal,” Italian American Review 3.2 (Summer 2013): 105–106.

44. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 310–12.

45. Ibid. 430, fn.28.

46. Alvin W. Gouldner, “Anti-Minotaur: The Myth of a Value Free Sociology,” Social Problems 9.3 (1962): 200.

47. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 164.

48. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 22–23.

49. Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1966), 3.

50. Ibid., 4.

51. Violet Johnson, “Culture, Economic Stability, and Entrepreneurship: The Case of British West Indians in Boston,” in New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, ed. Marilyn Halter (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995).

52. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 310.

53. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 157.

54. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 310.

55. Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1963).

56. Kourvetaris, 107.

57. Ibid., 110–11.

58. Matthew Frye Jacobson, Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post-Civil Rights America. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 181, 196.

59. Mavratsas, Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement, 23.

60. Ibid., 438, fn. 42.

61. Jacobson, 183.

62. Ibid., 187.

63. Ibid., 203.

64. Karen Brodkin, How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 52.

65. Oscar Lewis, Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty. (New York: Basic Books, 1959).

66. See, for instance, the documentary The Greek Americans, directed by George Veras (Veras Communications Inc., 1998).

67. The term neoconservative “applies broadly to a prominent group of intellectuals who, once considered to be on the left, are now on the right,” and who, unlike liberals, thought that society is difficult to change, and, unlike conservatives, accepted the “welfare state though not in its present incarnation.” Mark Gerson, ed., “Introduction” in The Essential Neoconservative Reader, foreword by James Q. Wilson (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1996), xiii, xiv.

68. Jacobson, 198.

69. Peter Berger and Richard John Neuhaus, To Empower People: From State to Civil Society. (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 1977).

70. James Q. Wilson, “Foreword,” in The Essential Neoconservative Reader, ed. Mark Gerson (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1996), ix.

71. Jacobson, 201.

72. Mavratsas, “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America,” 159.

73. Ibid., 159.

74. Gerald Meyer, “Theorizing Italian American History: The Search for an Historiographical Paradigm,” in The Status of Interpretation in Italian American Studies, ed. Jerome Krase (Stony Brook, NY: Forum Italicum Publishing, 2011), 164, 165.

75. Brodkin, 52.

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “White Ethnicity: A Reappraisal.” Italian American Review 3.2 (Summer 2013): 99–128.

Berger, Peter. “Foreword.” In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, edited by Marilyn Halter, vii–ix. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995.

Berger, Peter, and Richard John Neuhaus. To Empower People: From State to Civil Society. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute, 1977.

Berger, L. Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge . Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1966.

Brodkin, Karen. How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says about Race in America . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1998.

Georgakas, Dan. “Response to Charles C. Moskos.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora XIV nos. 1&2 (Spring–Summer 1987): 63–72.

Gerson, Mark, ed. “Introduction.” In The Essential Neoconservative Reader, foreword by James Q. Wilson, xiii-xvii. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. 1996.

Glazer, Nathan, and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City . Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1963.

Gouldner, Alvin W. “Anti-Minotaur: The Myth of a Value Free Sociology. Social Problems 9, no. 3 (1962): 199–213.

Halter, Marilyn. “Introduction–Boston’s Immigrants Revisited: The Economic Culture of Ethnic Enterprise.” In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, edited by Marilyn Halter, 1–22. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post-Civil Rights America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Johnson, Violet. “Culture, Economic Stability, and Entrepreneurship: The Case of British West Indians in Boston.” In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, edited by Marilyn Halter, 59–80. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995.

Kitroeff, Alexander. “The Moskos–Georgakas Debate: A Rejoinder.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora XIV nos. 1&2 (Spring–Summer 1987): 73–78.

Kourvetaris, Yorgos A. “Greek American Professionals and Entrepreneurs.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora. Special Quadruple Issue, The Greek American Experience XVI, nos. 1–4 (1989): 105–128.

Oscar, Lewis. Five Families: Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty. New York: Basic Books, 1959.

Mavratsas, Caesar V. Ethnic Entrepreneurialism, Social Mobility, and Embourgeoisement. The Formation and Intergenerational Evolution of Greek-American Economic Culture . PhD diss., Boston University, 1993.

Mavratsas, Caesar. “Greece, Cyprus and Greek America: Comparative Issues in Rationalization, Embourgeoisement, and the Modernization of Consciousness.” Modern Greek Studies Yearbook 10/11 (1994/95): 139–69.

Mavratsas, Caesar V. “Greek-American Economic Culture: The Intensification of Economic Life and a Parallel Process of Puritanization.” In New Migrants in the Marketplace: Boston’s Ethnic Entrepreneurs, edited by Marilyn Halter, 97–119. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1995.

Meyer, Gerald. “Theorizing Italian American History: The Search for an Historiographical Paradigm.” In The Status of Interpretation in Italian American Studies, edited by Jerome Krase,164–184. Stony Brook, NY: Forum Italicum Publishing, 2011.

Moskos, Charles C. “Georgakas on Greek Americans: A Response.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora XIV nos. 1&2 (Spring–Summer 1987): 55–62.

Moskos, Charles C. Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. 2nd ed. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1989.

Veras, George, dir. The Greek Americans. Veras Communications Inc., 1998.

Wilson, James Q. “Foreword,” in The Essential Neoconservative Reader, edited by Mark Gerson, vii–x. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1996.