A Radical Life

by Peter Pappas

In November of last year, I changed my email after very many years and sent a message to that effect to about a half-dozen people, old friends with whom I either still kept in touch, if only sporadically, or with whom I at least did not want to lose touch. Dan was among the latter. It had been decades since we’d seen each other; from time to time, we’d exchange emails, almost always because I was on some broadcast list from one of Dan’s many activities and affiliations. This time, I’d contacted him about my change of electronic address, although I naturally added, given the circumstances under which the world has been living for the last couple of years, that I hoped he was well and would remain so.

Because of the routine nature of the communication, I did not expect a reply. So, I was happily surprised to receive a brief but, for me, welcome response that he was 83 (a minor miracle to anyone who knew of his family background and personal medical history) and still hanging in there. (Or words to that effect. I don’t keep my emails, so I’m citing Dan’s note from memory.) I immediately replied in turn that he should stay well.

A couple of weeks later, on November 24, my wife, Melanie, and I flew to Paris. As soon as we went up to our hotel room, the first thing I did, as always, was take out my laptop and put in the hotel codes to make sure the Internet was working. A few emails coming in confirmed that it was. I noticed, however, that the first one was from Alexander Kitroeff—with whom I have permanent but irregular contact—and, although we were anxious to take a long walk after our flight from Greece, where we live currently, I opened it immediately. I turned to Melanie. “Dan’s died,” I said.

***

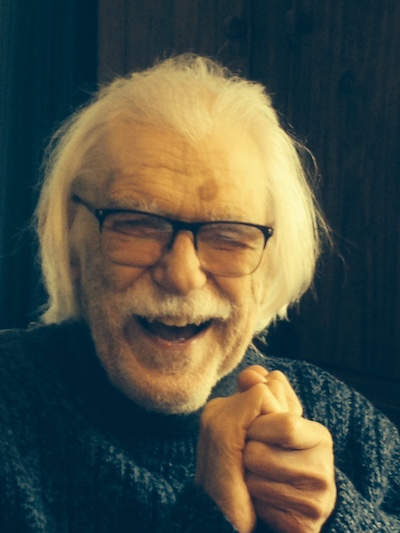

I met Dan at a party. I realize now that that fact in itself tells one more about him than any biographical detail. Because, if nothing else, Dan was an exuberant human being. In Greek, we’d say πληθωρικός. He just exploded conviviality and enthusiasm and, above all—an almost dead word now in any language—camaraderie. Long after the particularities of one’s relationship with Dan disappear into time, what stands out clearest and sharpest is his laugh (constant?) and smile (wry, knowing, or, more often than not, a simple physical expression of internal contentment and peace of mind).

That party in which I met Dan is representative of the time we met. (I ask the reader’s pardon for relying on memory, which I know is untrustworthy, but when Hurricane Sandy detonated over New York City, my wife and I lost the personal archives that we kept in a storage facility.) It was the mid-seventies. I now recall those years not only as almost a utopian age of political acuity and intellectual engagement, but of incredible fun and even optimism. The party in question was held in the relatively tiny studio of the Greek ceramicist Yiannes (Iordanidis) on Seventh Avenue South in the West Village. Yiannes hosted a lot of parties at that time, mostly as a way of gathering a wide range of artists or academics—Stephen Antonakos, Ed Malefakis, Stathis Giallelis immediately come to mind, as well as bona fide celebrities such as Mikis Theodorakis or Edmund Keeley—with nobodies like me, who’d dropped out of my first stint in graduate school in 1976, surviving from one job to the next, and just happened to be Yiannes’s friend. But I remember him telling me that he’d invited Dan to the party that night because he wanted the two of us to meet. (Yiannes was always bringing people together that he thought should know each other.)

I think I’d recently published a review of The Engagement of Anna the previous year (1975) in a new radical (albeit academic) film journal out of Chicago (if I remember correctly) called Jump Cut. I suppose the editors were happy with my piece because, soon after, I was asked to review Scorsese’s newest release and the hottest picture at the time, Taxi Driver. A problem ensued after I’d submitted the review, however. When the manuscript came back with the editors’ comments, I was asked to change “fishermen” to the non-gendered “fisherfolk.” Don’t ask me what “fishermen” was doing in a review of Taxi Driver. I don’t remember and I lost the manuscript a long time ago. What I do remember, though, only because I was so upset by the entire thing—as well as being intimidated, as I saw my fledgling opportunity to “break into” serious film criticism being quickly aborted—was that my reference was to Greek social reality, in which, at least as far as I knew and understood, was primarily, if not utterly, a male occupation. Yes, of course, women helped men with the maintenance of nets and certainly with the dispatch and commerce and, especially, processing of the fish once caught, but the actual fishing was done by men. To this day, I don’t know why I insisted on this point, but I did. I considered myself a leftist and certainly considered myself a feminist. But I just felt that the intellectual demand made of me, no matter how trivial—it was just one word, after all—was wrong. The term “political correctness” was not yet in vogue in 1976; we on the left just called it “Stalinism.” Long story, short: the piece never ran and I never wrote for Jump Cut again.

It was after that episode that I met Dan. But I have to say a few words here about what “meeting” Dan Georgakas meant to a twenty-something Greek American graduate-school-dropout lefty. Detroit: I Do Mind Dying (co-written with Marvin Surkin) had just been published the year before. Dan was also on the editorial board of Cineaste, the most prominent left-wing film journal in the States at the time. Years earlier, he’d cofounded, with Ben Morea, the anarchist group Black Mask (which later became Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers), which was briefly associated with the Situationist International, although later repudiated by Guy Debord himself, of all people, for being “too mystical.” (Black Mask must have also been the only group in the history of postwar American radicalism with the singular honor of being charged by Abbie Hoffman—again, of all people—with “inciting rioting at public events.”) Meanwhile, before Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, Dan had published two books on Native American history, The Broken Hoop and Red Shadows, for Doubleday’s Zenith paperback series, written for junior and senior high-school students and designed, according to the New York Times, “to give minorities a fair deal in the study of American and world history and literature.”

The point is that Dan was a figure of enormous radical presence in New York City. And as far as the tiny, essentially nonexistent, left-wing Greek American community was concerned, he was huge. Above all, he was the real deal. A radical in every sense of the word. He was as far away, and opposed, to the typical Greek leftist—straitlaced, party-line, existentially timorous to the point of panic, prim and proper and puritanical to within an inch of his or her life (“Πρώτοι στα μαθήματα, πρώτοι στον Αγώνα”)—as anyone could possibly be. And I was as bad as the rest of them. I’ll never forget how shocked, shocked, I was when I read my first piece of film criticism by Dan. It was from Cineaste in 1975 and entitled, “Porno Power.” One of the first jolts to my prudishness was coming across the word “fuck.” I was still under the mind-sapping intellectual dominion of The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, Αυγή, and Ριζοσπάστη. Dan, on the other hand, had freed himself from that kind of conformist cognitive authority a long time ago. I quote the close of his article:

One can only speculate at the power a film might have that combined erotic realism with a Marxist critique of contemporary society. One can only wonder what an erotically realistic film made by a feminist might look like. One of the writing school dictums is that there are three major things to write about—sex, religion and politics. Those who have brushed aside pornography as purely negative might do well to revise their thinking.

I don’t think it need be said that, at this point in the West’s “development,” it is difficult to imagine anyone being able to publish ideas like these in an established left-wing journal (or any kind of reputable publication, for that matter). This is not the place to argue hashtag politics—passive, fundamentally capitulatory, and demonstratively ineffective, in my humble opinion—or even whether Dan was right or wrong about the ostensibly liberating possibilities of pornography. I have to confess, however, that I almost broke out laughing when, after so many decades, I reread the line about combining erotic realism with a Marxist critique of society. Its naïveté is beyond dispute; but what makes it naive is also what makes it wonderfully, phantasmagorically utopian and the kind of emancipatory wishful thinking that one no longer finds on the left, which is why the left is dead. And for anyone who thinks that Dan was just a fool for radical love, I recommend a re-viewing of the famous scene in Reds in which John Reed/Warren Beatty and Louise Bryant/Diane Keaton make love to the voluptuous orchestration of the Internationale under the musical direction of Stephen Sondheim. I suspect that the great cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, who won an Oscar for the film, would have loved to have been allowed to “combine erotic realism with a Marxist critique” without any restraint—especially since he’d shot Last Tango in Paris a decade earlier. Here, as in so many other things, Dan was ahead of the rest of us by some distance.

***

At that introduction on Seventh Avenue South, Dan was extremely generous. He told me he’d read my piece in Jump Cut and I told him the “fisherfolk” story. He just laughed (that laugh again) and said something about Jump Cut being overly academic. Would I be interested in writing for Cineaste? Was the Pope Catholic? And so began a beautiful friendship, for as long as it lasted, and it lasted long enough, by any measure.

Nineteen seventy-six turned out to be very busy for me, mostly because of Dan. He’d become a member of the editorial board of The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora (JHD), founded and then still published by Indiana University sociologist Nikos Petropoulos. It’s no accident that my first piece in the JHD appeared in the August issue that year (the subject being—quelle surprise!—Yiannes’s ceramic sculpture, although, to be fair to Dan, Yiannes might have had something to do with that). In the winter, Cineaste published me for the first time, with an essay on The Travelling Players.

Prior to this and at his offering, Dan and I had driven to the Modern Greek Studies Association (MGSA) conference in Chicago—that is, Dan drove and I rode. (I still don’t have a license: the difference between growing up in Detroit and growing up in New York City.) The “symposium,” as the MGSA rather preciously calls its conferences, was the fifth in its history but the first about “The Greek Experience in America.” I should clarify here that, by the time I’d met Dan, I’d been working—first as a copyeditor and ultimately as editor—for the extraordinary publisher, and unsung hero, of Greek American letters, Leandros Papathanasiou, who’d started Pella Publishing Company one or two years before. So, Dan was on the lookout for material for the JHD, while Leandros had sent me to Chicago for possible book projects.

I don’t think anything came of Chicago for Pella, but by the fall of the following year, Leandros had agreed to take over and seriously upgrade The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora. After forty-five years, I can’t remember the exact sequence of events: whether, in other words, Dan approached Leandros as a mediator for Nikos Petropoulos, who could no longer afford the costs of publishing, or whether he spoke to me first and asked me to broach the subject with Leandros, but, in any case—given our relationship at the time—it would have been strange for Dan not to have discussed this with me before speaking with Leandros, at least in order to feel me out on what I thought Leandros’s reaction might be.

In the event, the winter 1978 issue (Volume IV, Number 4) of the Journal was the first published by Pella, with an editorial board comprising Paschalis Kitromilides, Yiannis P. Roubatis, Dan, and myself. As I had something to do with that board’s composition, I have to say that I consider its creation a singular achievement. At a time when we were all, except for Dan, still in our twenties, and neither Paschalis nor Yiannis had finished their dissertations (the former at Harvard, the latter at Johns Hopkins), who could possibly have guessed then that Paschalis would go on to become the leading intellectual historian of Greece, not only of his generation but of many a generation; or that Yiannis would go on to become Greece’s government spokesman, a Member of the European Parliament, and, most recently, head of the Greek intelligence service? If nothing else, we proved that Greek intellectual inquiry of the highest order structured by a left-wing analytical perspective was possible in the United States.

In 1979, I got married and my wife, Melanie Wallace, and I moved into the third floor of a Sterling Place brownstone in Park Slope in which Dan was also living. By the summer of the following year, Melanie was asked to join Cineaste’s editorial board, which made evening get-togethers in our apartment almost a nightly ritual as Dan and Melanie had to confer, or just schmooze, over Cineaste business. These nightly gatherings were greatly abetted—and often encouraged—by the fact that, in addition to my wife’s intellectual and literary gifts, she is also an unusually good cook. Dan loved whatever Melanie made, and was not shy in expressing his appreciation with a plate of this or that.

After about three years, Melanie resigned from the editorial board and I stopped writing for the magazine. Our reasons were not identical but they were related. Suffice it to say that collective intellectual enterprises are inherently fraught, but especially so when they’re bound together by ostensibly common ideological conviction. Anybody who’s even briefly lived a life on the left has experienced what used to be called “sectarian” dispute, but is, in fact, psychological and existential moments of consciousness when you realize that “the left” is a very broad church (and, like Christianity, often equally irrational) and one’s definition of it is not necessarily—indeed, may well be significantly opposed to—the definition of your “comrade” sitting across from you and gazing at you more and more suspiciously (or sadly or simply mystified). I should also add here that a couple of weeks before Melanie and I got married, I’d returned to Columbia, this time to its doctoral program in film, so, inevitably, my sense of movies was affected by the new intellectual environment in which I was seeing them.

By the early eighties, consequently, the intense period of my relationship with Dan was over (and Melanie and I had also moved out of Brooklyn to Manhattan), and we only saw or spoke to each other occasionally. Dan had resigned from the JHD’s editorial board after the spring 1982 issue, with Alexander Kitroeff replacing him that summer. Nevertheless, he returned as a writer by the mid-eighties. I left the Journal after the publication of the 1989 issue—a “special quadruple issue” on “The Greek American Experience” guest-edited by Charles Moskos and, who else?, Dan Georgakas. (The very notion of a “quadruple issue” speaks to how difficult putting out the magazine had become by that point.)

Meanwhile, in 1986, my day job had become editor of the The GreekAmerican, a weekly published by Fannie Petallides-Holiday, who’d originally approached me for her English-language edition of Proini, but agreed to my counter-proposal of a new newspaper free of any baggage. It goes without saying that I approached Dan at the time to contribute to the paper, which he gladly did.

Four years later, I left The GreekAmerican; two years after that, Melanie and I moved to Athens; and two years after that, we were back in New York because I’d been hired by the Foundation for Hellenic Culture. Dan, and his wonderful partner, Barbara Saltz, would come to the Foundation’s events from time to time. (Barbara’s truly irrepressible smile and natural laughter outdid even Dan’s; the two of them were meant for each other.) I resigned from the Foundation in 2000. Some point between the late nineties and that year, therefore, was (probably, again, as I’m depending on memory) the last time I saw Dan.

***

Dan had an enormous effect on my life in two ways. First, paradoxically, he made me realize I was American. Until I met him, I always thought I was “Greek,” although I’d been brought to the States by my parents at the age of ten months. But my parents never assimilated to American life, and brought me and my brother up as Greeks. Of course, it was an absurd delusion on their parts, not to mention on mine or my brother’s (who was born in the Bronx), but much of immigrant life is built on delusion (about the host country, about the country left behind, about any number of issues of “identity”—that malignant term of insidious confusion). So, meeting Dan was, as strange as this may sound now, the first time I actually met an American of Greek descent who was profoundly, irreducibly American . And by that I mean someone who was so engaged with the contradictions, and opposed to the manifest and undeniable evils, of American life that he could be nothing else but a native son of a culture and a society that he desperately wanted to rehabilitate and reconstruct. Which is why Detroit: I Do Mind Dying was such an explosive text for me. I mean, here was a book co-written by a Greek American about black people! For a brief period when I was a little boy, before we moved to New York, my family had lived on the South Side of Chicago. I thus imbibed racist panic in our extended Greek American household (aunts and uncles living on separate floors) with my daily cereal. And no matter how “left-wing” I’d become subsequently, I was still fundamentally oblivious to African American reality, despite the civil rights and Black Power movements of the first twenty-four years of my life. And here came Dan, not only writing about black people but about the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, for heaven’s sake. I cannot stress this enough: it changed my life. The moment I actually saw the connection between me and black people is the moment I consciously became American. A few years back, Dan said that “racism is the cancer of American life.” Faulkner portrayed it as the genetic disorder of American life. In any case, it’s only when an American confronts racism as America’s daily reality, and most fundamental historical truth, that (s)he genuinely understands America—and becomes an American.

Dan made the connection for me. And then drove it deeper into my psyche. I first heard of Johnny Otis from Dan. Granted, I was never a big rock ‘n’ roll guy (until I met Melanie), but you’d think a Greek American lefty with pretensions of cultural breadth would have had some kind of wider horizons than Theodorakis and Vamvakaris, or, on the other hand, Dylan, Pete Seeger, and the Beatles. To this day, I am deeply embarrassed by my ignorance at the time.

A few days ago, as I was writing this, my wife came to me with a copy of Edward Abbey’s Fire on the Mountain, which she picked off our bookshelves. “When did we get this?” she asked. I didn’t know, I replied, but I was sure that I must have ordered whatever books of Abbey’s we have because he was a favorite writer of Dan’s and, again, Dan had introduced me to his work.

I’m sure you get the picture at this point. Black America. Environmental radicalism. It all came to me directly from and through Dan. Dan forced me to shed my Greek camouflage and admit to my American truth hiding in plain sight. I am eternally grateful to him for that. (Although, to be fair, my wife continued the effort after Dan and carried it much further, to my vast improvement and delight.)

And then there’s one other thing, equally fundamental, if not more so. It took me a very long time to grasp the enormous debt of gratitude the world owes to Engels. His enormous financial generosity to Marx and, after Marx died, to his daughters (Laura and Eleanor, especially), quite literally changed history. None of it would have been possible if Engels, despite his deep hatred for his family’s textile enterprise, did not consciously, and painfully, decide to continue working for it in order to subsidize his, but mostly Marx’s, labors to organize and expand the socialist movement worldwide. When Dan’s parents died, they left him a small inheritance. (I never asked how much, but I never thought it was anything life-altering.) Dan invested that money, and wisely husbanded it, in order to have a permanent supplement to his income, which, because of the nature of his writing and teaching (canceled classes or writing projects), was irregular. But Dan was the only leftist I ever met who admitted to active investing—and, naturally, was the only one I’ve ever met who understood capitalism in more than a knee-jerk, ideologized fashion, and in a very personal way, as a structure that actually produces wealth and, therefore, entitlement for some and endless misery and impoverishment for mostly everybody else.

He advised me not to accept economic insecurity passively, especially because he saw that Melanie and I were never going to settle on particularly remunerative, let alone lucrative, “careers,” but would live our lives unpredictably—as he had. So, he cautioned me that, given that America’s (and, to an increasing extent, the West’s) actually existing economic system crushes most people, we had to protect ourselves, especially as we got older. When we moved into Sterling Place, Melanie and I had $300 in our bank account (which, actually, we thought was a decent amount, or at least enough). We made sure through the following four decades-plus—including the worst financial crisis of our lifetimes in 2008—that we’d never become capitalism’s victims. Dan taught me that in rejecting capitalist order—what the French so astutely call la pensée unique—one also needed the capacity to survive that rejection. For most working people, that was impossible, of course, but for those of us privileged by education and—let’s be honest—bourgeois endowment(s) of some sort (Bourdieu’s social capital), we needed to protect our lives from the consequences of veering off the socially conventional straight and narrow.

***

In the days after Dan died, I came across a number of obits in the Greek American community. My immediate reaction was, frankly, distaste compounded by anger. The rewriting of history had already begun, just the day after Dan had died. The National Herald’s obituary at least contains the adjectival “left” or “leftist” twice—although not directly in reference to Dan—but the press announcement released a week after Dan’s death by the American Hellenic Institute is a classic example of the kind of biographical “rectification” that would have done the editors of Pravda proud once upon a time. One searches vainly for any hint of the words “left,” “radical,” “socialist,” or “anarchist.” More damningly, there is no mention—none!—of any of Dan’s many books. So much for “historical memory” as defined by the institutional pillars of Greek American life.

I’ll let Dan speak for himself. On the home page of his website, we find these first three paragraphs:

I was born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, where I lived for the first twenty-six years of my life. I have written about those years inMy Detroit: Growing Up Greek and American in Motor City and in Detroit: I Do Mind Dying. These books explore the roots of the fundamental ideas that have shaped my subsequent writing and activism.

I left Detroit with a fiercely anti-authoritarian mindset and a highly critical view of the ruling economic order. I have tried to use logic rather than faith and documentation rather than conjecture to advance my views. I advocate radical solutions to contemporary problems, but I think achieving something genuinely new also necessitates reanimating many traditional values.

I have written a dozen books and monographs on subjects as varied as cinema, radical movements, Native Americans, labor history, longevity, and Greek America. I also have written or edited five poetry collections…

“I left Detroit with a fiercely anti-authoritarian mindset … highly critical … of the ruling economic order. … I advocate radical solutions to contemporary problems.” And that marvelous coda: “I have written a dozen books and monographs on subjects as varied as cinema, radical movements, Native Americans, labor history, longevity, and Greek America.” I love that “and Greek America.” Not quite an afterthought, but a distinct parcel of a much wider and expansive intellectual and moral terrain.

***

As I wrote above, after some years, Dan and I reached an impasse over how we saw the world—a natural occurrence when any two intelligent human beings come together, but even more so when they’re both headstrong and invariably opinionated. Seen from a distance of forty years, however, it was … nothing. If I may be excused an impertinent ascent from the humble to the sublime, after Camus’s death, Sartre wrote of their friendship that: “He and I had quarreled. A quarrel doesn’t matter—even if those who quarrel never see each other again—just another way of living together without losing sight of one another in the narrow little world that is allotted us.” Dan and I never even quarreled. We just decided that disengagement was the best “way of living together without losing sight of one another.” I will miss him. I have missed him for very many years. But such is our fate in this narrow little world allotted us.

Peter Pappas

was involved with a number of editorial and cultural activities over many

years, both in the Greek American community and Greece.