Dan Georgakas: A Remembrance

by Kristin Lawler

To consider the life of the great Greek American antifascist Dan Georgakas is also to take a tour through every important iteration of revolutionary anarcho-syndicalist cultural politics in American history. In remembering his life and work, we honor the most creative, the most vital, the most solidaristic legacy of the labor movement and the left. These moments—the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Radical America, and Cineaste—rhyme. And the rhythm is a working-class counterculture composed of autonomy, power, freedom, solidarity, and art.

The thread that runs through these countercultural politics begins, of course, in Detroit. There, Dan, aware that institutionalized education in America failed to teach him anything about the racism that he saw all around him, connected with the Facing Reality and News and Letters group, attending their public lectures, reading CLR James with Raya Dunayevska and through them coming into contact with Cornelius Castoriadis and the Socialism ou Barbarie group, a major influence on the Situationist International. In addition, the Socialist Workers Party’s (SWP) weekly lectures brought Dan into contact with some of the folks who would become leaders in the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. His trajectory was, then, partly shaped by left intellectual and cultural institutions that were radically open, unorthodox, and focused on questions of culture and class; he spent his life continuing that tradition, building spaces, direct actions, and institutions animated by what Castoriadis called the radical imagination.

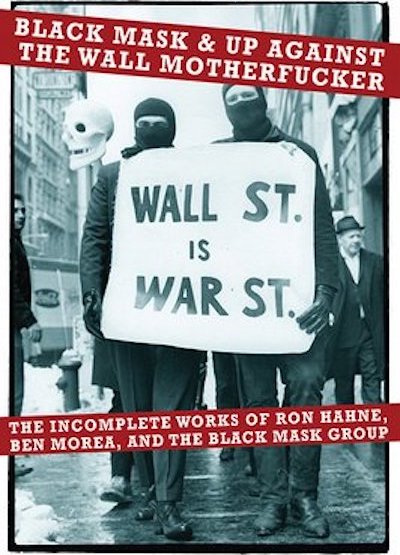

It’s not surprising that when he went to Rome to teach high school in the early sixties, he connected with Autonomist radicals, anarcho-syndicalists with a focus on power at the point of production (and reproduction) through the refusal of work, and on oppositional working-class culture. Back in the United States, he and Ben Morea famously set off the tiny but influential anarchist direct action group Black Mask, later Up Against the Wall Motherfucker. There are still few more powerful exhortations to open up this avant garde front in the class struggle than you’ll find in the inaugural issue of Black Mask, in which the group responds to a comradely strategic criticism:

… you question the relevance of a cultural revolution as part of wider revolution. The fact that you think only a small minority is concerned with culture is part of a basic misconception, which equates culture with western-bourgeois culture … [Vietnamese, African, and other cultural revolutionaries] are involved with a living culture which is what we hope to see rise throughout America, a living culture which comes from the creative spirit of man. With this we can change the stultifying classrooms, the inhuman city, the concept of work when it is unnecessary and everything else which is crushing life instead of allowing it to grow fully. This cannot be achieved without revolution, but neither can it be achieved without the creative force. Sure: close the war plants or the Pentagon or City Hall or the precinct station—but don’t stop there, let their culture fall too.[1]

Like Chicago Surrealists Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, Dan’s life’s work highlighted the connections between the cultural and class politics of Surrealism, the Situationists, and the great Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Dan worked with the Rosemonts, Paul Buhle, and others on the seminal student New Left publication Radical America, which Buhle once referred to as an “IWW/Situationist journal.” The IWW was at the very root of American countercultural class power politics: the strategy of sabotage, or “the conscious withdrawal of the workers’ industrial efficiency” at the point of production gave workers on the job leverage that they refused to either hoard or defuse through the signing of a contract. This was combined with a cultural strategy—in song, in art, in soapbox political standup comedy, in cartoons and newspapers, and in the kind of commoning that was typical of many Wobbly (IWW) spaces—that aimed to spread joyful rebellion against a dehumanizing capitalist system. Both the industrial and the cultural strategies were united by a refusal of Taylorist work discipline and a celebration of the libidinal, creative imagination that opposes it. And the Wobblies’ industrial unionism and cultural politics animated the Communist Party’s 1930s “cultural front”: not surprising then that the first literary journal Dan co-founded, in 1958, “sought to resurrect the political passions of the artists of the 1930s.”

Of the IWW, Dan wrote:

A distinguishing feature … was that rather than trying to win the allegiance of artists already recognized by the dominant culture, the IWW had the audacity to believe workers could create their own art. The aim was to liberate the imagination as well as the flesh. In the same way that the distance between leaders and members was consciously minimized, the IWW reduced the conventional gulf between artist and audience. IWW art was truly of, by, and for fellow workers. IWW posters were for street display, not for the gallery or museum. [Black Mask, of course, looked to symbolically destroy museums, starting with the Museum of Modern Art.] IWW literature was to be recited aloud, not read silently. IWW songs, jokes, and parables were to enter public consciousness as mass entertainment.[2]

Thus the political importance of film: it had the capacity to expand the imagination and to reach a popular audience. But it wasn’t only politics that kept Dan focused on film, or on any of the rest of radical culture. It was love, too. He was a true film fan, and he—in the journal he wrote for and served on the editorial board of, Cineaste, and in the rest of his body of work, from Detroit to Greece—was animated by the kind of critical vision that can only emerge from great love. This attitude is central to a life like Dan’s—a long and cheerful life of uncompromising radicalism.

This kind of life is a model of true opposition to the society of the spectacle, a society that makes workers into passive objects of capital accumulation and passive consumers of the ideological products that support it. Racism, of course, is a central feature of this ideology, and in the absence of radical cultural politics, the working-class movement is sunk. Dan reiterated this point one sunny day when members of the Situations collective interviewed him at his house (and at a local Greek diner) about Detroit and Greece, both “living laboratories” for the imposition of capitalist crisis. Acknowledging that in Detroit, the moment of potential working-class leverage to oppose deindustrialization and union busting had passed, he encouraged us to imagine a counter history in which the UAW in the late 1960s had let DRUM and the League lead the union. Instead, they’d let their shitty cultural politics—racism and a cozy relationship with management—get in the way of good working-class solidarity and militancy. The city of Detroit and the state of American labor today are both testament to his point:

Imagine what might have occurred if the [United Auto Workers] UAW had gone into alliance with League radicals rather than trying to crush them. League attorney Ken Cockerel who had won landmark civil rights cases could have been asked to use his considerable talents on behalf of the UAW. John Watson, who had turned a college newspaper into Detroit’s third daily, could have been asked to try his hand at making the UAW paper into a dynamic resource. Organizers such as General Baker and Mike Hamlin could have been asked to try their hand at organizing the South. Chrysler activist Ron March could have been allowed his victory at Dodge Main to go forward rather than being denied by the UAW seizing ballot boxes with the assistance of the police. A militant UAW could have staged massive strikes and other actions challenging auto’s flight to anti-union states and an automation program designed to reduce rather than retrain workers. That didn’t happen. Instead, the arrival of the black liberation movement at the doors of the UAW was met with so much hostility that it generated a new slogan: UAW means U Ain’t White.[3]

In the same interview, Dan also counsels that “we won’t find any blueprints for change in past strategies, just an orientation that must be reshaped for our times and conditions.” Radical film, antifascist struggle, the revolutionary cultural politics of the IWW, Black Mask, and the League—they are not blueprints. But the common thread among Dan’s political commitments indeed provides an orientation that we can use. It’s imperative that we rise to the example that he gave us and to ground ourselves in the most vital traditions of the left—and if Dan Georgakas studied it or participated in it, it is likely one of these traditions—without getting mired in stale orthodoxy, and to think clearly, always with a sharp and uncompromising eye for the possibility of liberation.

Kristin Lawler

is Professor of Sociology at the College of Mount Saint Vincent in New York

City. She is author of The American Surfer: Radical Culture and Capitalism, published by

Routledge in 2011, and the co-editor of San Diego State University Press's

forthcoming Flow and Roll: the Political Ontology of Skate and Surf. Her

essays appear in numerous edited collections, including most recently

Brill’s 2019 volume Nietzsche and Critical Social Theory, and

Palgrave’s 2020 collection

Back to the 30s? Recurring Crises of Capitalism, Liberalism, and

Democracy,

She is a contributing member of the editorial collective and the book

review editor of the journal Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination and a board member

of the Institute for the Radical Imagination.

Notes

[1] Ron Hahne and Ben Morea, Black Mask and Up Against the Wall Motherfucker: The Incomplete Works of Ron Hahne, Ben Morea, and the Black Mask Group. (New York, PM Press, 2011), 7.

[2] Stewart Bird, Dan Georgakas, and Deborah Shaffer, Solidarity Forever: An Oral History of the IWW. (Chicago: Lake View Press, 1985), 23.

[3] Living Laboratories: from Detroit to Athens and Back. A conversation with Dan Georgakas and the Situations Collective, Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination, (2016): 9–27.

Editor's note: For a Dan Georgakas interview on his political activism discussed above see

here.