Documenting Diaspora: Effy Alexakis’ Framings of Transcultural Belonging

by Andonis Piperoglou

Many migrants (like my mother), and their descendants (like me), share the experience of trying to belong in an unfamiliar place—ways of belonging that histories in polities like the United States and Australia frequently miss in an overriding determination to tell stories of a unified national core. Making a new home can be a complicated and at times alienating process and in the thick of it, migrants (and their descendants) may not think of themselves as being part of this imagined national core. When someone like Effy Alexakis drifts in with her camera, bringing her creative eye to the many sites of our migrant-cum-diasporic worlds, something fascinating occurs.

Alexakis for forty years has aimed her camera on documenting the many layers of the Greek diaspora in Australia — the forgotten and the remembered, the neglected and the cherished, the old and the new, the private and the public. As a committed documentary photographer, capturing the many layers of Australia’s social pasts is important to her. The way we live, they way we laugh, the way we think, the way we remember. Constantly active in her practice, Alexakis has become a diasporic cultural practitioner of immense value. She loves an unassuming people nestled on a couch or armchair in the comfort of their own home, sitting on an urban bench, or in their place of work — a mechanic in his garage, a fruiter on a street corner, a café owner with a stained apron.

Documenting the many layers of Greek diasporic pasts in Australia is important to her. Since the 1980s, she has traversed across the many landscapes of Greek Australia, revealing an assortment of common faces in familiar dwellings. “Hellenism,” Alexakis compellingly asserts in a recent publication Forty Photographs: A Year at a Time, “is not a national characteristic but a continuous source of energy.” Alongside her life-partner, Leonard Janiszewski (a social historian and curator at Macquarie University’s Art Gallery), her photographs have been printed in publications that have come to hold pride of place on many Greek Australian bookshelves. Alexakis and Janiszewski’s first three volumes, Images of Home: Mavri Xenitia (1995), In Their Own Image: Greek-Australians (1998), and Greek Cafés and Milk Bars of Australia (2016; reprinted in 2022) have become cherished representations of Greek culture in Australia, while also standing as emblematic examples of how to practice Australian public history for a thirsty and thriving ethnic audience that wishes to see its history respected on the page.

Via a strict self-imposed artistic practice and commissioned photographic endeavours—like being one of six chosen photographers to capture Australian inclusion during the 1995 UN International Year of Tolerance — Effy cannot go past a facet of Greek culture in Australia without thinking about how to document it. Her desire to preserve, via the medium of the photograph, for future generations of onlookers who may find interest in our transcultural pasts is unrelenting. In tandem with Janiszewski, she has devoted a life to giving face to what we could think of as another Australia — a super-diverse Australia that is not limited to ethnic stereotypes and misrepresentations.

Alexakis likes to get to know the people she photographs. She takes portraits with her subjects; she does not merely take pictures of them. Conjuring feelings of affinity and admiration, she is motivated to capture the humility of subjects. This proximity is revealed in the numerous images on display at the exhibition Viewfinder: Effy Alexakis, which is currently on show at Hellenic Museum in Melbourne. The retrospective — made possible via a collaboration with the museum’s CEO and Head of Curation, Sarah Craig — charts Alexakis’ 40-year-long practice. Showcasing a layering of themes that have underpinned her personal and professional journey to understand Greek diasporic heritage in Australia, the exhibition reframes and refocuses our gaze.

Images she took in 1980s and 1990s reveal a promise to counter limiting institutional archival practices and document everyday Greek diasporic worlds, while more recent images depict playful reworkings of invented folklore and heartening empathetic endeavours that took place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meshed diaspora experiences like a Vietnamese-Greek-Australian wearing a fustanella/φουστανέλλα documents how traditional costume can be freshly embodied, while images of a Reverand at a local a soup kitchen that operates out of a church hall centres the value of kindness and gifting.

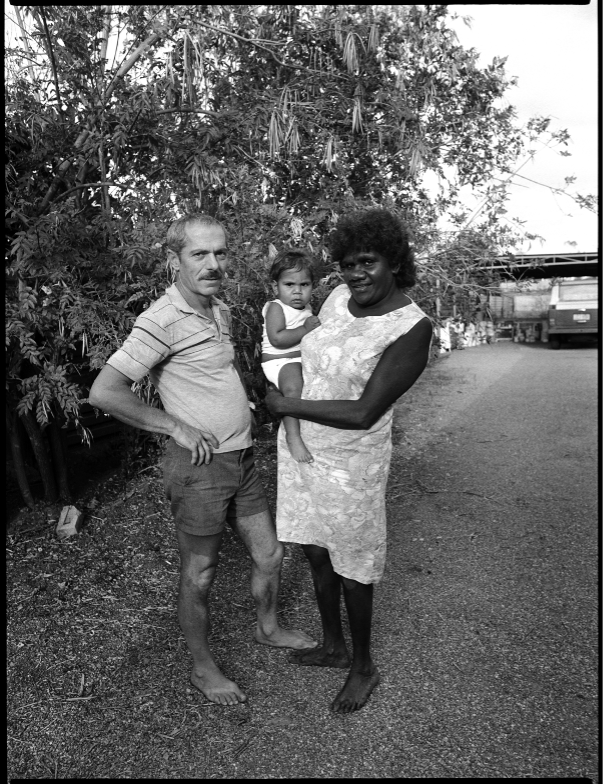

Alexakis takes considerable care in ensuring a person’s desire to present themselves as themselves. She has a gift for capturing a sincere portrait. An honest representation of how people wish to present their lives is part of her talented style of documentation. Engaging with a range of subjects, this frankness manages to reorientate common assumptions about migrant pasts and presents by giving focus to how migration transitions into permanent settlement (however loaded and challenging that experience can be). Her images force us to consider what values we place on Greekness and what standards we place on our layered transcultural heritages. A widower (her own mother), a young gay writer (Christos Tsiolkas before he received international literary attention), an Indigenous mother (who married a Greek migrant), a determined businesswoman, a daughter on a family holiday — when seen in unison, we see how Greek-Australianness is alive in difference. How Greek-Australianness is alive in diversity.

Her devotion to documenting the Greek experience in Australia is fed by her own child-of-migrant story, in which she helped run a fish ‘n’ chip shop in Padstow—a suburb in south west Sydney. Indeed, the first image in the exhibition accompanying volume Forty Photographs: A Year at a Time is of her parents, Maria and Spiro in the family’s fish ‘n’ chip shop. Taken in 1982, her parents look back at us — but also at her, their child, a budding professional photographer. You can almost feel the heat from the deep fryer. Chicko Roll advertisements (an iconic deep fried Australian savoury snack inspired by the Chinese spring roll), and pricing listed in chalk on a blackboard menu (a plain hamburger cost 70c back then) form a backdrop that reveals how much our worlds have changed.

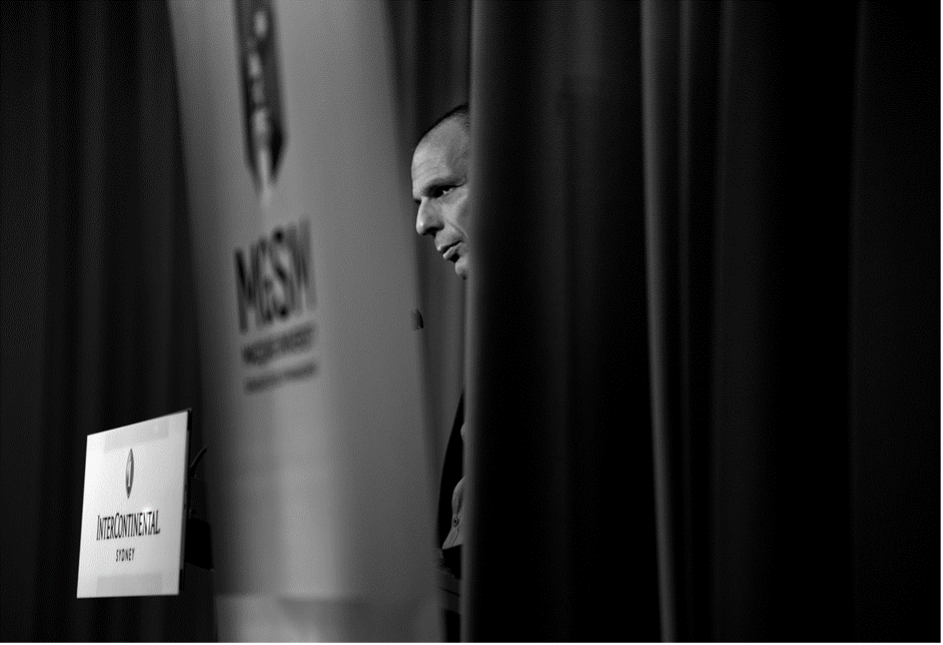

Alexakis has withstood and embraced the plethora of characters and spaces that make up the transcultural fusion of Australianness with Greekness. Committed to documenting diaspora’s diversity, she has been attentive to both conventional and alternative representations — a federal senator, an Athenian street beggar, her own grieving family, a Supreme Court Judge, actors getting ready backstage, an empathetic priest, a global intellectual, and an elderly woman in a retirement village are within her vast remit. She does not shy away from divisions of class and culture, nor of youthfulness and aging.

Although often recording in black-and-white, the colour of life vividly flows through her portraits. There is puzzling familiarity in the quality of her concerted effort to document the diaspora. Though I have never met or visited many of the people and locations that she has captured with her watchful eye, the many photographs she has taken makes me feel that I have: somewhere in myself, somehow, I recognize the individuals and places she has shot and recorded.

In particular, the various images of elderly people holding photos of their forebears reminds me of the cross-generational power a historical photograph can yield. Likewise, with the shared experience of migration in an already inhabited land: on a conscious level I feel, as a historian of the Greek diaspora, like I share her steadfast desire to rekindle and reframe the past for a better politics historical inclusivity in the present.

The finale image that wraps up the exhibition’s accompanying catalogue returns to her parents — or rather, a parent. Her father Spiro has now passed, and we are invited to resee her mother, Maria. We do not see, however, this Yia Yia’s elderly face. Instead, we are drawn to another image. Her mother is holding a Certificate of Registration for Aliens. A form of documentation that was part of an assimilationist Australia. We can see how the government documented Maria. Address: Redfern. Nationality: Greek. Place of Birth: Sykia. Disembarked in Australia on: 18 October 1956. Port: Sydney. Alongside these details is stapled a photograph of a more youthful Maria. A bureaucratic purple stamp of the Australian Department of Immigration is pressed over the image, acting as a mode of official certification for the state system. Wearing what appears to be a pearl necklace, Maria’s hair is evenly parted, and she awkwardly smiles back at us. Cutting through the state surveillance document, Effy’s photograph of her mother holding the identification form manages to simultaneously capture both the vulnerability of reinvention — that many migrants, knowingly or unknowingly, take-on — and the absoluteness of ageing. Taken during the pandemic, the image also acts as an example of how Alexakis found herself caught in a personal and political endeavour of relearning the experience of her mother’s migrant journey. Maria, we are informed, travelled on a ‘bride ship’ and married three weeks after her arrival to Australia.

Time is not suspended in Effy’s photos. They are studies full of life, of pasts that have relevance to our contemporary moment. When viewed in concert, her images act as a timely reminder while migration is often tied to charged politics and policy, it is actually people in place. The cumulative effect of Effy Alexakis’ documentary photography is a respectful, humane, and historically informed social take on our transcultural worlds.

When I decided to become a historian, I hoped that I could access multifaceted cultural interactions between in the numerous archives and library scattered across Australia. Such interactions, however, were hard to find until I started looking at Alexakis’ photographs. It is within her now vast visual archive that we can find the social dynamics of Greeks outside of Greece.

To contemplate the dynamics of migrant belonging through Effy’s documenting eye is to be drawn into a strangely familiar, deeply benevolent artistic worldview that has significant relevance to my own sense of belonging today, and, I hope, our collective sense of diasporic belonging in the future.

Dr. Andonis Piperoglou is Hellenic Senior Lecturer in Global Diasporas at the University of Melbourne.

Editor's Note: Listen to Effy Alexakis speaking about her work (in Greek) here.