Spectacular Incorporations: American Sports, Ethnic Heritage Night, and Greek America

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

“Society has officially declared itself

to be spectacular.”

–Guy Debord1

Unlike in the recent past, when entertainment in sports arenas was directed toward the average fan, today’s spectator fun also targets ethnic and underrepresented racial communities in professional sports. The connection between American sports and ethnicity is rich, and the cultural performances of ethnic groups is now a staple in Major League Baseball (MLB) and the National Basketball Association (NBA) games. These spectacle-like displays circulate widely through mainstream as well as ethnic media, producing lasting images in the public memory.

For instance, there’s the Phillie Phanatic, the mascot of the Philadelphia Phillies, frolicking with Greek American folk dancers during pregame festivities. There’s a Mexican mariachi band with sombreros and the full regalia, the Chicago Bulls mascot dressing up to match them. The San Diego Padres’s Swinging Friar sitting royally in a giant “Little Italy” chair marking the ethnic neighborhood in San Diego, as two cheerleaders stand on each side framing the Friar. Fans in the same event sported a limited-edition Padres-themed Italian Night hat. Sushi, egg rolls, and lo mein specially offered to the fans of Orlando Magic, a professional team in the NBA. A Chinese lion dance at the half-time of the Chicago Bulls–Houston Rockets game. Japanese merchandise, such as hats written in Kanji, “Ichi Roll,” and promotional “San Shi!” headbands during a Seattle Mariners MLB game. Sumo wrestlers simulated through inflatable costumes. Tennis player Michael Chang, a prominent Chinese American athlete, being honored during the Chinese Appreciation Game sponsored by LA’s Dodgers. Fans singing the Greek national anthem during postgame adulations of Giannis Antetokounmbo, an ascending NBA superstar.

Cultural otherness is made spectacularly visible in the nation’s sports-centered entertainment through dramatic displays of dance performances, flag waving, and commodities branded with ethnic symbols and icons. Starting at least in the 1990s, and taking off in the early twenty-first century, the NBA and MLB have systematically incorporated ethnic themes into the game, part of a marketing strategy to increase the fan base of the respective sport.2 Ethnic Heritage Nights devoted to American racial or ethnic groups—Chinese, Filipino, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Jewish, Latino, Mexican, Polynesian, Russian, Serbian, Tamil—are now an entrenched fixture of professional basketball arenas and baseball parks, encapsulating this standardized ethnicization. They have often but not necessarily organized around the numerous marquee international players, remarkable athletes associated with American ethnic communities, or American-born stars from underrepresented racial communities that left an indelible mark on American sports. Houston Rocket’s Yao Ming (China), Milwaukee Bucks’s Giannis Antetokounmbo (Greece), Sacramento Kings’s Omri Casspi (Israel), Los Angeles Clippers’s Milos Teodosic (Serbia), Atlanta Hawks’s Jeremy Lin (Taiwanese American), Los Angeles Dodgers’s Hideo Nomo (Japan), and Chan Ho Park (South Korea) are among the names of superstars around which sports and ethnicity have been intersecting.3

What drives this ethnicization? Popular media register the economic motivation behind the intertwining of sport with ethnicity and underrepresented race. But what does the institutionalization of ethnic heritage nights tell us about the making of ethnic and racial identity in the United States? What are the implications of capitalizing on ethnic and racial identity in the mainstream sports arena?

To understand this phenomenon, first let’s consider larger developments in the American economy and the role of culture in economic processes such as marketing, as well as two facets of the growing internationalization of American sports. One the one hand, more and more international players come to play in these respective leagues. On the other hand, the NBA and MLB more and more seek to generate global visibility and the associated revenues associated with broadcasting rights and the selling of merchandise. The incorporation of Otherness into the sports industry is largely linked with the corporate strategy to use culture as a tool promoting consumption to niche ethnic groups at home as well as global audiences. Ethnicity offers, as I will explore, a cultural resource for its power to produce and promise a unique experience luring and retaining prospective consumers while recognizing and contributing to the visibility of cultural differences.

Located at this economic and cultural nexus, ethnic heritage nights represent a relatively new development in the public performance of ethnic identity in the United States. In this stage of development, ethnic cultural expressions travel, so to speak, from the spaces in which they have conventionally been establishing themselves since the 1960s ethnic revival, notably the ethnic festival, or earlier, the ethnic parade, to mainstream spaces of spectacular entertainment. This is made possible by the synergy of ethnic groups willing their representation in these spaces and sports franchises embracing this inclusion. This partnership expresses the latest stage of ethnic adaptation to dominant socioeconomic structures of American society, namely the commodification of culture in the context of “multinational capitalism.”4

I build on a particular case study, the Greek Heritage Night in MLB and the NBA, as a point of departure to reflect on the implications of this adaptation for an American ethnic group. The event certainly fosters ethnic identity, asserts loyalty for the (American) nation, and cultivates love for the local team and the game. But it also enables a bolder public expression of identity, one that expresses political loyalties beyond the American nation. These identity statements are accommodated, even encouraged, by the hosting sports franchises in, one must note, a scripted manner, staged for the sake of the fans in attendance as well as television audiences globally. This situation points to the mediating power of American sports franchises such as the NBA to be enabling venues for diaspora political identifications. The NBA’s global aspiration5 offers the conditions for creating transnational spaces—an American arena hosting post-American political allegiances—for the benefit of American ethnic communities at home but also respective audiences in their historical homelands.

I am fully aware that my analysis enters a sociocultural field of immense theoretical and empirical complexity, of which I only explore selective paths of inquiry. In this respect, my foray takes the form of an essay, asking more questions than it answers, offering tentative insights, and certainly less conclusiveness, than the fully formed argument of an article would. My main aim is to outline a map identifying the major players shaping the field “American sports/ethnicity” in the present—corporations operating at a multinational level, the spectacularization of leisure, the place of ethnicity in public culture—tracing some of their historical continuities and discontinuities, and pointing to their interconnections within the field. The mapping circulates an initial understanding of this phenomenon for public attention and further conversation.

Corporate Ethnicization and Spectacles of Ethnicity

The tendency toward celebrating ethnicity is not unique to the sports industry but rather extends to other aspects of American popular entertainment. Disney, for example, is a global company that exemplifies the corporate turn toward ethnicization. Its iconic symbol, Mickey Mouse, has been extensively nationalized both in merchandise and simulated performances featuring Mickey, in ethnic attire, greeting visitors, obliging to requests for dancing, and modeling his costume at ethnic-themed events. An ethnicized Mickey, along with the mythological character Hercules, for instance, was the center of attraction in the 2013 “Opa! A Celebration of Greece” in California’s Disneyland. One can purchase a wide array of ethnic-themed products from Disney’s multifaceted leisure and entertainment complex. French, Mexican, Chinese, Japanese, or Greek Mickeys, or a Disney Magic Mediterranean cruise are among the available commodities.

The centrality of cultural themes in the marketing of goods and services underlines the intertwining of economy and culture for the purpose of consumption. This interfacing marks a particular stage in capitalism, associated with the economic importance of cultural images and meanings. The decline of manufacturing resulted in the ascendancy of culture—music and film for instance—as a vital force in the economy. Hence the importance of promoting consumption via cultural meanings. Attaching a product with rich symbolism, addressing its cultural—as opposed its utilitarian and intrinsic—value to prospective customers, and attempting “to create an identification between producers and consumers” to effect consumption, is now a conventional marketing strategy.6 The advertising slogan “Just Do It,” for example, brands a shoe as a sign of relentless determination to achieve a goal, a value that invites identification with the brand via the message of resilience, and generating the desire for ownership of the product that signifies it. Cultural critic Paul du Gay aptly captures this connection between the marketing aspect of the economy and the production of cultural meaning:

more and more of the goods and services produced for consumers across a range of sectors can be conceived as “cultural” goods, in that they are deliberately inscribed with particular meanings and associations as they are produced and circulated in a conscious attempt to generate desire for them amongst end users. The growing aestheticization or “fashioning” of seemingly banal products—from instant coffee to bank accounts—whereby these are sold to consumers in terms of particular clusters of meaning indicates the increasing importance of “culture” to the production and circulation of a multitude of goods and services.7

The production of desire for commodities via the route of cultural appeal directly connects with Ethnic Heritage Night, given that the increasing buying power of consumers affiliated with ethnic groups makes ethnicity an attractive economic niche to American corporations. In response, businesses have been reshaping their marketing strategies. “Corporate industry leaders,” Marilyn Halter writes, have been “turning away from mass advertising campaigns to concentrate on segmented marketing approaches. One of the most successful of the segmenting strategies has been to target specific ethnic constituencies.” Ethnic heritage nights, associated with special group ticket packages, and themed merchandises and commodities are part of this redirection that targets ethnic-niche consumers.8

The images of Disney’s Mickey and Philly’s Phanatic sporting Greek folk costumes point to a marketing technique shared across the entertainment industry: theming. Theming entails staged motifs centering on ethnic characters, décors (rock and roll, pirate bars), places of imagination (Disney’s Magic Kingdom), or other simulations that pervade the American cultural landscape. Theming produces spectacles, visually dramatic displays staged to enchant the public. Theming fosters dreamlike, magical experiences: it encourages emotionally laden flights of the imagination, creating fantasies of being elsewhere in time and across space and cultures. It is touted as a route for enthralling escapes from the ordinary and, in tandem, the exciting experience of the extraordinary. Theming centers the way that corporations, including sports franchises, organize entertainment, emulating Disney, the latter seen as a model in the art and politics of theming. As former NBA Commissioner David Stern stated:

They [Disney] have theme parts … and we have theme parks. Only we call them arenas. They have characters: Mickey Mouse, Goofy. Our characters are named Magic [Johnson] and Michael [Jordan]. Disney sells apparel; we sell apparel. They make home videos; we make home videos”9

Indeed, the NBA’s radical transformation from its “cultural and economic decline” in the early 1980s into today’s mega “global media entertainment” industry represents a most dramatic example of the cultural dominance of Disney’s principles, in fact the “Disneyization of society.”10 As a promise to fantastic and “funtastic” experiences in this spectacularized world, theming represents a long-standing corporate move to attract diverse publics to sites of consumption.

The ethnicization of the entertainment industry contributes economic as well as cultural capital to corporations. In the economic domain, it is consistent with strategies mobilized by the likes of Disney, NBA, Benetton, and Mattel, Inc., among others, for global expansion. It also serves local marketing imperatives to inject new spectacular forms of enjoyment for the purpose of expanding the fan base and renewing interest among spectators quickly jaded by repeatability and predictability. In the cultural realm, ethnicization communicates democratic openness to cultural difference, adding value to the company as multicultural friendly. Corporate ethnicization brings economic and cultural interests together in investing products with clusters of ethnic meaning to attract new and retain existing consumers, as it contributes to branding franchises as pluralistic.

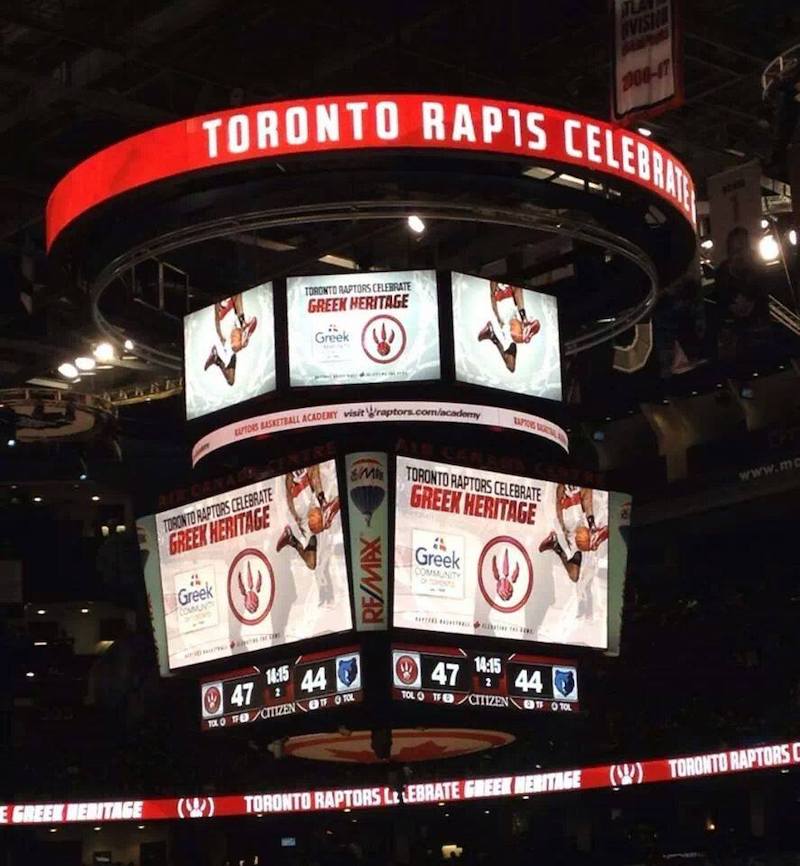

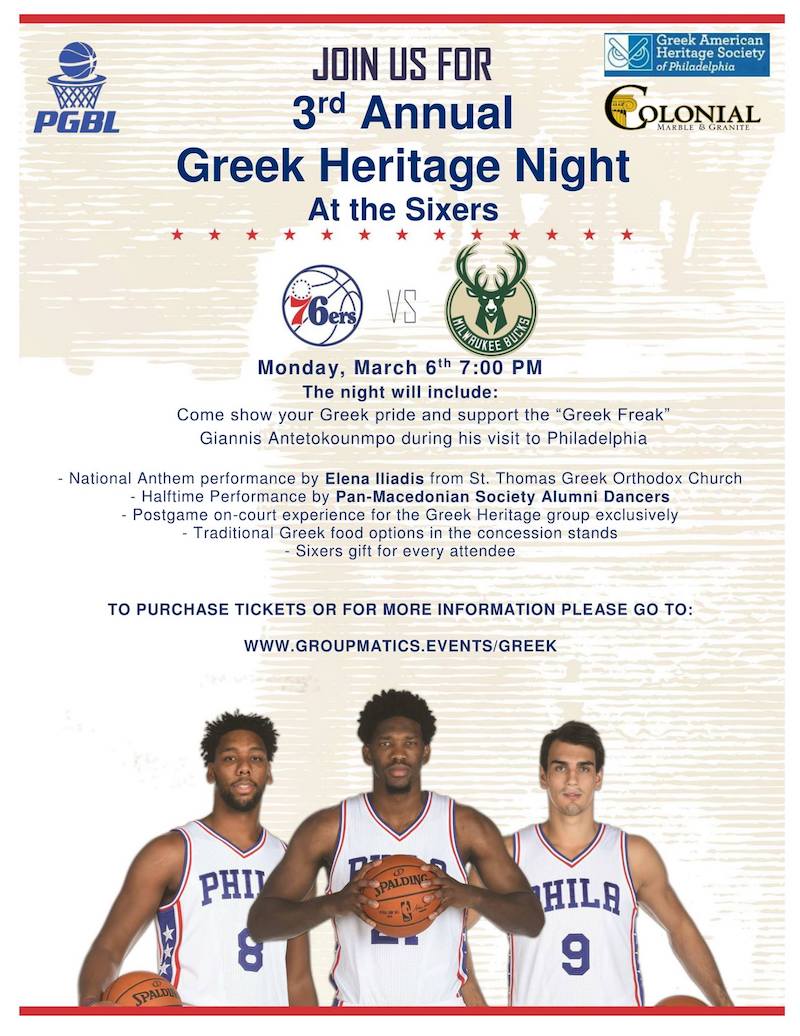

The Greek Heritage Night

How does Greek theming play out in the NBA or MLB? What is its significance and for whom? The theming is acted out in the now institutionalized Greek Heritage Night, a multifaceted event entailing pregame and half-time folk dance performances in ballparks and basketball arenas, the official performance of the American national anthem by a Greek American, the availability of Greek food, and, in some instances, the showing of promotional videos about Greece. Postgame charity parties to support humanitarian causes on behalf of Greece as well unofficial singing of the Greek national anthem are also part of the festivities. A product of partnership between Greek American local, regional, and national organizations such as the American Hellenic Institute (AHI) or the Philadelphia Greek Basketball League (PGBL), with sports franchises, it is marketed as a themed event and cast in the promotional rhetoric of honoring local Greek American communities, promoting Greek culture, generating ethnic pride, and commemorating Greek American athletes such as baseball legend “Golden Greek” Harry Agganis. Though Greek heritage nights have been organized in MLB venues as early as 2005, the event has been gaining momentum in the NBA, its force emanating from the superstar status of Giannis Antentokoumbo, a charismatic player who was born in Athens, Greece, to immigrants from Nigeria. Giannis, as he is commonly called, started playing basketball in Greece, receiving Greek honorary citizenship for contributing to the Greek National team. He was drafted by the Milwaukee Bucks in 2013, becoming a sensation and catapulting the Bucks to dramatic success, consistently filling its arena to capacity. Greek Americans celebrate Giannis as a symbol of (successful) Greek identity in the diaspora. Whenever the Bucks play in cities with a sizable Greek American population such as Toronto, Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, Greek heritage nights are organized around half-time performances of folk dancing, postgame signing of autographs, waving Greek flags, and Giannis joining Greek spectators in the much-televised, postgame unofficial singing of the Greek national anthem.

Greek Heritage Night does not stand alone in the history of public performances of U.S. Greek identity. A certainly new cultural phenomenon, it exhibits remarkable similarities—but also recognizable differences—in relation to one of the most visible Greek spectacles of identity, namely the ubiquitous Greek festival. Both utilize visually striking costumes, flags, food, folk performances, and other hypervisible symbols of ethnic identity. Both involve spectacular displays connected with leisure, entertainment, and consumerism. I build on a shared feature, folk dancing, to illustrate the continuities and discontinuities between Greek Heritage Night and the festival.

A crucial difference between the two lies in their spatial and cultural organization. The festival takes places within the demarcated boundaries of an ethnic event; it is set apart, spatially and organizationally, as a distinct genre. Since their inception, festivals have been staged adjacent to churches—in temporarily transformed parking lots—or within ethnic neighborhoods, where organizers belonging to the community determine their content and scope, deliberately staging culture as an exclusive ethnic commodity for sensory and material consumption. The trope of authenticity, commonly employed in ethnic festivals to attract spectators from the outside, guided the all-ethnic display of food, dancing, and ethnic-motif merchandise, including art crafted by “ethnic” artists.

In contrast, Greek heritage nights entails ethnic performances taking place within an eclectic array of disparate cultural expressions within the ancillary entertainment space of competitive sports. The showcasing of Greek culture is one display among several others of different styles and forms, whose only commonality lies in their spectacle-like function. In this eclectic configuration, a pentozali, a traditional dance from the island of Crete, is followed by the performance of a cheerleading squad, followed by a marching band, then by contests involving the participation of fans, and finally by give-aways of merchandise like t-shirts, all contributing as cultural and material ancillary products to the making of the spectacle.

This implosion of different cultural forms within a single space represents a wider socioeconomic turn in postmodern economies. During the industrial revolution and throughout modernity, the availability of new inventions and products was largely differentiated in space; particular goods and services were offered in site-specific, specialized spaces. In the modern world, George Ritzer writes, the “wide variety of products led to a parallel differentiation in the settings in which they could be consumed. Modernity . . . was characterized by highly differentiated and rigidly separated means of consumption: the butcher shop sold meat, the baker bread, the greengrocer fruits and vegetables.”11 Similarly, ethnicity was largely performed in exclusively ethnically marked spaces.

But in today’s highly consumerist economy, the spatial organization of consumption has been radically altered. A dazzling multiplicity of goods and services—from spa treatments to sampling local foods, and from the availability of banking to movie theaters—are increasingly offered within the same space. Alongside thrill rides, theme parks offer hotel accommodations, shopping, and dining within their premises. Hotels and casinos fuse into each other in the mecca of spectacle, Las Vegas. Even museums prominently incorporate shopping into the experience of heritage and culture.

Several rationalities drive this implosion, efficiency being an obvious one. Overworked professionals starved for free-time can now combine shopping, household errands, and family fun in one trip. Urban renewal offers another major motivation. New, mixed-use spaces of entertainment, brand downtowns as desirable destinations for suburban dwellers, radically transforming previously depressed areas in American cities. The repurposing of athletic stadiums into multipurpose districts accommodating multiple consumer needs is a case in point. Arenas are now parts of mega downtown developments offering sports, shopping, arts, leisure, and residence opportunities. The Downtown Commons (DoCo) in Sacramento is a case in point. It encompasses a two-level outdoor mixed-use entertainment, shopping, and arts complex, developed around the new arena for the local NBA team, an approximately $507 million project. DoCo has been designed to revitalize the downtown, “replac[ing] the area's former label, Downtown Plaza, a name synonymous with the image of an empty, dilapidated urban core.”12 Other cities follow suit. Milwaukee has invested private and public funds to inaugurate Fiserv Forum, the new home for the Bucks, a $524 million “arena that sits at the center of a massive 30-acre downtown district” and envisions turning itself “into an entertainment destination for fans from all over the Midwest.” The conjoining of sports and entertainment is seen as the driving force for urban as well as regional economic development.13

Sports arenas, malls, theme parks, museums, heritage sites, airports, among other venues, are part of a constellation of “new means of consumption” sites where leisure interfaces with consumption in spectacular combination.14 Their dependency on a person’s physical presence presents a predicament that investors and corporations cannot possibly take for granted. In the age of online shopping, private consumption competes relentlessly with public shopping. Hence the intensification of efforts to spectacularize, as I mentioned, in-situ shopping: to construct it as an extraordinary, and therefore unique experience. Making this experience magical, a dazzling engagement of both senses and imagination, is driven by corporations to lure customers out of the comfort of their living rooms. Like so many aspects of social life, the new spaces of consumption are guided by rational planning around issues of efficiency, order, security, and surveillance. An additional calculation is to stage a thrilling, spectacular experience in the form of extraordinary technologies, like giant television screens, extravagant shows, simulations, sensory overload through booming sounds, music, striking colors, and eye-catching logos. DoCo, for instance, “is really supposed to be more of an experience than even a mall.” Consuming a glass of champagne in the place is no longer enough. It must be a spectacular experience, fizztastic!15

The incorporation of ethnicity in American sports contributes to this spectacularization, performing a number of functions, all consistent with the rational calculations of contemporary consumer culture. For one, as I have mentioned, it is designed to target new niche audiences, both domestically and internationally. It is directed, in other words, to American ethnic groups and global markets, which it relentlessly pursues. In this capacity, it is significant to note, Greek Heritage Night fosters national affiliation in addition to the hosting nation. In the process, it creates new (or builds on an existing base of) local fan loyalty. “You gonna cheer for the [Greek] flag or the team?” a journalist asked a Greek American boy during a Phillies Greek Heritage Night. “Both flag and team” was the answer.16

Theming in the entertainment industry offers a route to generate wonderment, setting in motion the imagination, feeding fantasies. It is staged to enchant spectators. Ethnic theming as a new form of entertainment counters consumer fatigue of spectacle repeatability. Consider, for example, how the semiotics of a spectacle associated with ethnic theming—folk dance—may contribute to enchantment. Dance and music stimulate the senses, contributing to the sensory overload aimed by the spectacle. Folk dancing may generate fantasies of harmony and nostalgia for an idealized past. Images of traditional costume and group dancing around shared steps perform a close-knit, socially cohesive community, simulating continuity with the pre-modern past. They communicate deep collective belonging in contradistinction to impersonal individualism and modern alienation.

Different spectators, of course, consume the same spectacle differently. Still, ethnographic work has shown a correlation between the authenticity of an ethnic event with general public interest in that event, in the context of Cajun festivals, in Louisiana:

The paradox of commodified ethnicity is that it can easily provide a vicarious sense of primordial identity even to non-group members. Although Cajuns are more likely than non-Cajuns to attend festivals, the latter do participate in large numbers. At Festivals Acadiens, the most self-consciously ‘‘authentic’’ ethnic event, the latter actually predominate. Vicarious ethnicity may actually be the key to much of contemporary resurgent ethnicity. Commodified ethnicity can provide a sense of being connected to a meaningful past (albeit a somewhat weaker sense) to out-group members as well as in-group members.17

But it would be erroneous to extrapolate from this insight to assert the validity of an equivalent vicarious consumption of ethnic performances in a sports arena. Festivals and ethnic heritage nights offer dramatically different contexts for cultural consumption. Unlike the festival, where the encounter between the ostensibly “non-ethnic” visitor and the showcased ethnic culture is purposeful—one attends a festival because one wishes to specifically partake to the particularity of its ethnic space—the Ethnic Heritage Night stages a random encounter in which any “interest” in the half-time ethnic portion of the spectacle is probably purely coincidental, and may trigger only fleeting attention or even indifference. For some it might stand for a practice devoid of meaning; it might represent an image pleasant for some, amusing perhaps for others. In either case there will be no knowledge about its history and cultural significance, a depthless, empty signifier. Gauging the effect of ethnic heritage nights on spectators requires ethnographic examination.

Still, a preliminary analysis at the level of Greek Heritage Night’s cultural production provides useful insights. Folk dancing, let us note, adds yet another value in the context of ancillary sports entertainment. Folk dancing traverses the folk past, modernity, and postmodernity. It has “traveled effectively” with immigrants across the traditional village, from which it originates, to American ethnic modernity in which it has endured in ethnic community life and thrived as public staging of Greek identity, to postmodernity, in which the society of the spectacle permits it to enter spaces of national entertainment.

Two attributes endow folk dancing with value beyond commodity status, an attribute that may generate wonderment. First, the fact that dancers participate voluntarily, with no immediate monetary rewards, places their performance outside the economic calculability that pervades contemporary social exchanges. Their public performance represents community service and “ethnic pride,” with the dancers, in turn, enjoying visibility and participation in a national spectacle. This is primarily a symbolic rather a material exchange. Second, the fact that the dancers are connected with an ethnic community where folk dancing is an integral part of everyday, celebratory, and ritual sociability, both for insiders (community life) and outsiders (festivals), animates in the arena an element lacking in corporate spectacles: it (re)introduces a cultural order characterizing early modern spectacles. The early modern “spectacular society” “tended to be an integral part of, and emerged from, everyday life (e.g., a country fair)” whereas today’s “society of the spectacle” is passive. “People watch [spectacles] because they are alluring, but the spectacles are put on for them; people are not a part of them.”18

I have juxtaposed Greek festivals and Greek heritage nights in their respective socioeconomic contexts to illustrate how Greek Heritage Night represents a new mode of ethnic incorporation into American consumer culture via corporate-sanctioned ethnicization. However, Greek Heritage Night is more than a spectacular cultural commodity filling seats in stadiums and arenas. Certainly commodified, it undoubtedly offers a stage to affirm and reinforce identity too. In the semiotics of Greek Heritage Night, Greek American spectators communicate who they are and how they want to be seen by others through richly symbolic practices: waving or draping themselves in the Greek flags, singing the national anthem, wearing jerseys of the local as well as the Greek national team, and performing televised ethnic dances in a mainstream event. Promoted by Greek Americans, accommodated by managers of sports franchises, and consumed by various publics, Greek heritage nights produce positive ethnic identification. The phenomenon performs important cultural work beyond American consumerism, within which it certainly participates. It empowers Greek identity in the United States.

I wish to caution against the view of Greek Heritage Night as a fleeting, superficial ethnic signifier, an ephemeral expression disconnected from the social life of the ethnic group. To situate the significance and implications of Greek Heritage Night, it is productive to think of it in relation to the notion of Greek America as network.19 The concept of network departs from conventional views of ethnicity as a homogeneous group or shared collective culture. Rather, it opens up a new way of mapping Greek America, one that simultaneously focuses our attention on specific sites where Greek identity is produced in the United States (the festival, the language school, the family, the media, the Modern Greek Program in the University, the NBA arena, the film festival, the ethnic community) while it “expands our field of vision” to their multifaceted interconnections but also disconnections.20 Not all sites—the nodes—are connected within the network, and not all the links are readily visible. One task by scholars is to foreground connections not immediately discernible, to reflect on how developments within a node may impact distant others.

A brief mapping of a particular Greek heritage night, one animated in the context of the Philadelphia Sixers vs. Milwaukee Bucks NBA game, illuminates some of the interconnectedness that this ethnic celebration sets in motion. Now in its fifth season, the event is made possible through a partnership between the Philadelphia Greek Basketball League (PGBL), an amateur adult league and the Sixers franchise. The Greek American Heritage Society of Philadelphia is also involved.

Established in 2007, PGBL represents an organization that brings together sports, leisure, ethnic identity, and community social organizations. A history of its formation traces its establishment to experiences associated with a particular organization, the Greek Orthodox Youth Association (GOYA), designed to promote fellowship within the bounds of Greek Orthodox parishes. Local and regional basketball tournaments are part of GOYA social life, regulating leisure time, and fostering sociability within an ethnoreligious setting. The foundational narrative of PGBL attributes its creation to the initiative of two close friends from their GOYA days looking to create a venue in continuation to their GOYA basketball experience; PGBL was the end product of this initiative, defining itself as more than athletics, but rather a social institution nurturing ethnic-centered sociability and friendships.21 Enlisting the volunteering of local and regional dance groups, which also perform in Greek festivals, PGBL’s sponsoring of Greek Heritage Night exemplifies the expansion of an already powerfully intermeshed social network—parish ethnoreligious youth programs, ethnicity-based leisure activities, the ethnic festival—outside the boundaries of the community and into the spotlight of a regional and national spectacle, a Sixers game.

Building on the notion of Greek America as network, I have placed Greek Heritage Night as a key node mobilizing intracommunity institutions to create yet another node for the expression of Greek identity, one enabled by a new historical contingency: American sports franchising sanctioning ethnic theming. The sports industry’s inclusion of ethnic groups translates into the latter’s integration into American spectacular consumption. From a Greek American point of view, the social and cultural consequences of this incorporation are immense. For one, the inclusion legitimizes ethnic identity, even identification with a transnational Greek national identity when fans sport jerseys of the Greek national team and sing the Greek national anthem. Situating Greek Heritage Night in this manner recognizes the event beyond a (facile) reading of it as an ephemeral—and therefore readily disposable—ethnic expression, an empty signifier. Instead, as the example of PGBL shows, the production of a local Greek Heritage Night requires considerable social and public relations work, interfacing the ethnic group with dominant American institutions, reinforcing ethnic ties (and possibly producing new ones), interconnecting various organizations within the parish, and enabling the public affirmation of ethnic identity, all for the purpose of endowing great cultural visibility to Greek America. “To show our heritage” and “express pride in it” is a recurrent answer regarding the aim of participation. In this respect, Greek Heritage Night represent a new stage in the history of Greek American adaptations to the (ever-changing) dominant structures of American society. If ethnic festivals exemplify a successful adaptation within the context of ethnic revival, Greek Heritage Night represents a novel adaptation, one mobilized through collective ethnic initiatives, which taps onto thriving cultural forms—as a result of previous adaptations—this time in the context of American multinational capitalism. Greek heritage nights represent cultural continuity as well as a shift and variation in the history of Greek American public displays of identity.

The social construction of Greek identity around Greek Heritage Night contributes to the project of reproducing ethnic identity. Its incorporation into national spectacles legitimizes ethnic identity, a public affirmation that correlates with the noticeable presence of the Greek American youth in Greek Heritage Night. In addition to families bringing their children, academies and Greek language schools are also in attendance en masse. While scripted Greek identity in festivals has certainly contributed to the positive popularization of Greek cultural forms, particularly dancing, it is not rare for Greek American youth in small town or rural America to still feel the sting of peer devaluation of cultural differences, even in the twenty-first century.22 The national visibility of Greek Heritage Night—its very incorporation in a highly coveted event—offers yet another rationale for parents and individuals to make a convincing case that the mainstream’s acceptability of at least a selective range of Greek cultural forms, counters their devaluation elsewhere.

The Greek Heritage Night’s political work in the NBA is also noteworthy, at least as it pertains to its current articulation, its centering on the celebrity of Giannis Antetokounmpo. The adulation of Giannis as Greek represents a resounding public affirmation of conceptualizing Greek identity on the basis of cultural background and place of birth, not descent. It moves the contested conversation about Greek citizenship towards the basis of birthright (jus soli) and against the popular understanding of right of blood (jus sanguinis). It challenges nationalism’s view of identity in terms of ethnic purity, endorsing the inclusion of the children of interracial couples in Greek America as Greek and the offspring of immigrants in Greece as Greek citizens.23

Giannis’s postgame interacting with the Greek spectators advances yet another political expression of Greek identity. The fact that the accessibility of star players to the public is recommended as a facet of marketing24 certainly contributes to Giannis’s interfacing with Greek spectators, signing autographs and often encouraging the singing of the Greek national anthem. It is not uncommon to see spectators holding homemade placards communicating their affiliation with Ελλάδα (Greece), in Greek. What is more, the Bucks organization often tweets videos of these nation-loving rituals, sometimes even tweeting short phrases in Greek.

In these performances one witnesses an expression of national loyalty that is rarely, if ever, staged in Greek festivals. In their aspiration for global expansion, and their catering to marque international players and respective ethnic spectators, American sports franchises open spaces for public identifications beyond the (American) nation within mainstream national spaces. When Greek American kids sport the jersey of the Greek national basketball team, as they do during NBA Greek Heritage Night, they nurture an imaginary of transnational diaspora identification with Greece.

The Greek Heritage Night’s spectacular production and consumption of Greek identity no doubt dazzles, both in its emotional power to enchant and its political capacity to assert belonging. It enthralls the Greek American public and enhances ethnic confidence. It is the product of cultural politics simultaneously serving ethnic and corporate interests, a win–win situation in the sports world and the social game of representation.

At this point it is necessary to take a turn and reflect on the implications associated with performing ethnicity within the logic of corporate ethnicization. There seems to be an overwhelming social agreement over the undeniably positive value of incorporating ethnicity into spectacularized American sports. It is as if the merits of this inclusion go without saying. Spectacles, of course, are disputed. But in this case, to paraphrase Guy Debord, a pioneer trenchant critic of society’s domination by spectacle, what the spectacle showcases appears to be good and what is good is unfailingly bound to appear in the spectacle. Such is the power of the spectacle to naturalize itself as an indisputable social imperative. To return to the prefacing statement of this essay, “[s]ociety has officially declared itself to be spectacular.”

A sector of the society critiques the political work of the spectacle, seeking to undermine its power. As a pervasive mode through which we partake and understand the world, through the intertwined consumption of images and commodities–alluring vacations in exotic islands, awe-inspiring films, thrilling theme parks–the spectacle disengages publics from active citizenship. Spectacles are positioned to produce apathetic consumers. They erase historical memory. They are profit-driven machines calibrated to stream social life toward material consumption, placing it as the center of meaning. They worship collective experiences based on the consumption of images—flocking in urban spaces such as New York City’s Times Squares for the experience of the spectacular—instead of social interconnectedness. They lure spectators into dazzling yet superficial or falsified information instead of the understanding of social and political issues, which they hide. They mask gross class inequalities, at work in all aspects of spectacle production, which they render invisible.

While reading work discussing spectacles, a particular line gave me pause. In the world of spectacle, Tiernan Morgan and Lauren Purje write, “gradually, we begin to conflate visibility with value.”25 The spectacle not only privileges the visibility of things, it most importantly endows inherent value to the things it renders visible. I draw from this insight to point to three interrelated caveats regarding the corporate spectacularization of ethnicity:

(1) The privileging of certain cultural forms in ethnic heritage nights sidelines alternative, nonspectacular, cultural practices within an ethnic network. Catering to spectacular ethnicity, Ethnic Heritage Night is necessarily selective when it comes to the forms it foregrounds and inevitably reproduces. Will Ethnic Heritage Night-related ethnic pride, certainly empowering, translate into interest in alternative, not consumer-driven practices? Or will nodes within the network that are conceptually located at a considerable distance from the center of the spectacle atrophy?

(2) The success of Ethnic Heritage Night may provide the model, or, more precisely, furnish the cultural logic to shape ethnicity’s display in the public realm. If spectacularized ethnicity draws visibility, why not spectacularize the telling of ethnic history? The risk of producing spectacular history lies in the fundamental historical forgetting that such a representation engenders.

(3) The centering of Ethnic Heritage Night on identity-theming neglects the possible internal plurality of the particular identities that it celebrates. The apotheosis of Giannis as a Greek and Greek only, for instance, risks erasing Giannis’s family roots and their centrality in his growing up as a son of immigrants. Giannis’s recently expressed interest to explore his African roots serves as a reminder of his multiple cultural affiliations.26

To return to the case of Greek America: given its real force of spectacularizing identity, Greek Heritage Night presents prospects difficult to chart, and risks relatively easy-to-anticipate when it comes to the future unfolding of Greek America’s network. For those who rightly advocate the recognition of Greek America’s internal diversity, a Greek Heritage Night-related danger would lie in the prospect of the event contributing to the consolidation of Greek American identity around a limited core of scripted cultural practices, narrowing the range of this identity, sacrificing complexity. What is more, the possible proliferation of practices producing Greek America as spectacle in multiple nodes of the network will inevitably reduce cultural difference into a caricatured reflection of the dominant expectations of that difference. On the other hand, one cannot underestimate the power of Greek Heritage Night to animate new connections within the network. Cultural leaders as well as the wider Greek American public, including parents and the youth, may harness the ethnic energy it generates to pursue interest in other nodes of the network, or create new ones. The involved superstar athletes, though constrained by corporate scripts, also possess some agency to bring attention to the network’s complexity. Scholars, authors, journalists, and public intellectuals face the challenge of combating the spectacle’s propensities to reduce, hide, and erase historical memory and the plurality of cultural forms. Writing for the purpose of expanding the network is one mode to position ourselves against the shrinking of the network into spectacular extravagance. This writing operates within the parameters of this expansion, connecting the world of Greek American scholarship with popular entertainment and community activism, initiating lines of communication with various publics whose interest in, and response to, this piece, and therefore inclination or disinclination for a public conversation over shaping the expanse of the network, I cannot possibly imagine.

Yiorgos Anagnostou is a professor of transnational Modern Greek Studies at The Ohio State University. For his research profile see https://www.mgsa.org/faculty/anagnost.html

Notes

I thank Gerasimus Katsan for valuable feedback.

1. Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, trans. Malcolm Imrie (New York: Verso Books, 1990), 18.

2. Cyrus Farivar, “The NBA’s Ethnic Heritage Nights,” PRI, March 1, 2011, https://www.pri.org/stories/2011-03-01/nbas-ethnic-heritage-nights.

3. This is not to say that all star players enjoy uniform adoration from fans and the media. Jeremy Lin, for example, experienced racial discrimination on and off the court. If ethnic food is a commodity celebrated during heritage nights, references to it are also employed to hurl pernicious stereotypes. “Throughout his career,” David Leonard writes, Lin “has experienced prejudice from fans, who have yelled ‘wonton soup,’ ‘sweet and sour pork,’ … ‘beef and broccoli’ and ‘sweet and sour chicken’ in his direction” (150).

4. Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), xviii.

5. David L. Andrews, “The (Trans)National Basketball Association: American Commodity-Sign Culture and Global-Local Conjuncturalism,” in Articulating the Global and the Local: Globalization and Cultural Studies, eds. Ann Cvetkovich and Douglas Kellner (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997).

6. Paul du Gay, “Introduction,” in Production of Culture/Cultures of Production, ed. Paul du Gay (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 1997), 5.

7. Ibid., 5.

8. Marilyn Halter, Shopping for Identity: The Marketing of Ethnicity (New York: Schocken Books, 2000), 5.

9. Cited in David L. Andrews, “Disneyization, Debord, and the Integrated NBA Spectacle,” Social Semiotics 16, no. 1 (2006): 96

10. Ibid., 95, 96.

11. George Ritzer, Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption (Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 1999), 133–34. These distinct occupational niches were brought together in the modern supermarket, which still remained, however, a differentiated space in that it did not mix the activity of utilitarian shopping with other forms of leisure shopping and entertainment.

12. Ryan Lillis, “DoCo? SoBro? Kings New Branding of Downtown Commons Met with Praise, Mockery,” The Sacramento Bee, September 20, 2015, https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/city-beat/article35853153.html.

13. Dan Devine, “Why the Milwaukee Bucks’ New Arena is the NBA's Most Impressive,” YAHOO! SPORTS, August 21, 2018, https://sports.yahoo.com/milwaukee-bucks-new-arena-nbas-impressive-192841224.html.

14. Ritzer, Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption, 53.

15. ‘Sacramento Downtown Commons (DOCO) Perfect Fit for or Kings Fans and City,” October 17, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKtKF1ORaWw, (at 1min and 25 sec).

16. “Greek Heritage Night at the Philadelphia Phillies,” Cosmos Philly, June 14, 2018, https://cosmosphilly.com/greek-heritage-night-at-the-philadelphia-phillies/.

17. Carl L. Bankston III and Jacques Henry, “Spectacles of Ethnicity: Festivals and the Commodification of Ethnic Culture among Louisiana Cajuns,” Sociological Spectrum, 20, no. 4 (2000): 402–403.

18. Ritzer, Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption , 10.

19. See Artemis Leontis, “The Intellectual in Greek America,” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 23, no. 2 (1997).

20. William Stroebel, “The Hyphenated Hyphen: Turkish-in-the-Greek-Script American Literature,” Ergon: Greek/American Arts and Letters, December, 18, 2018, http://ergon.scienzine.com/article/articles/the-hyphenated-hyphen-turkish-in-the-greek-script-american-literature.

21. See https://www.phillygreekball.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=125&Itemid=205.

22. Christina Koinoglou, “Greek Dancing from the Point of View of a [Millennial] Second Generation Greek American,” In their Own Words: OSU Students Write about Greek America, April 19, 2019, https://u.osu.edu/narratives/2019/04/19/greek-dancing-from-the-point-of-view-of-a-millennial-second-generation-greek-american/2018.

23. “In July 2015 the much-debated law 4332 was voted in, giving the right to Greek citizenship to the children of migrants born and/or raised in Greece,” https://g2red.org/announcement-on-the-3-years-since-the-voting-of-the-citizenship-law-for-the-second-generation/.

24. Irvine Clarke III and Ryan Mannion, “Marketing Sport to Asian-American Consumers,” Sport Marketing Quarterly 15 (2006). On the fifth Greek Heritage Night in Philadelphia, however, the Bucks franchise denied Philly Greek fans a postgame meeting with Giannis (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mnJWupLHagI&fbclid=IwAR0_y-4NeL60xM8Yo9ACdPKjFmAICrbQ-ndtI1FuuX_HFaVYJenydcrWAJ0), citing his need to concentrate on the game and a recent injury.

25. Tiernan Morgan and Lauren Purje, “An Illustrated Guide to Guy Debord’s ‘The Society of the Spectacle,’” HyperAllergic, August 10, 2016, https://hyperallergic.com/313435/an-illustrated-guide-to-guy-debords-the-society-of-the-spectacle/.

26. Marc J. Spears, “‘The Greek Freak’ Wants to Go Back to His Nigerian Roots,” THE UNDEFEATED, March 5, 2019, https://theundefeated.com/features/bucks-giannis-antetokounmpo-greek-freak-wants-to-go-back-to-his-nigerian-roots/. It should be noted that the ascription “Greek freak” assigned to Giannis introduces a degree of ambiguity to his Greek identity, requiring further analysis. Most recently, Giannis has displayed public interest in his family’s roots, a gesture that counters his containment, externally imposed, within the single identity category “Greek,” inviting the public to acknowledge his syncretic affiliation.

Works Cited

Andrews, David L. “Disneyization, Debord, and the Integrated NBA Spectacle.” Social Semiotics 16, no. 1 (2006): 89–102.

Andrews, David L. “The (Trans)National Basketball Association: American Commodity-Sign Culture and Global-Local Conjuncturalism.” In Articulating the Global and the Local: Globalization and Cultural Studies, edited by Ann Cvetkovich and Douglas Kellner, 72–101. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1997.

Bankston III, Carl L., and Jacques Henry. “Spectacles of Ethnicity: Festivals and the Commodification of Ethnic Culture among Louisiana Cajuns.” Sociological Spectrum, 20, no. 4 (2000): 377–407.

Bryman, Alan. “The Disneyization of Society.” The Sociological Review 47, no. 1 (1999): 25–47.

Clarke III, Irvine, and Ryan Mannion. “Marketing Sport to Asian-American Consumers.” Sport Marketing Quarterly 15 (2006): 20–28.

Debord, Guy. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Malcolm Imrie. New York: Verso Books, 1990.

Devine, Dan. “Why the Milwaukee Bucks’ New Arena is the NBA's Most Impressive.” YAHOO! SPORTS, August 21, 2018. https://sports.yahoo.com/milwaukee-bucks-new-arena-nbas-impressive-192841224.html.

du Gay, Paul. “Introduction.” In Production of Culture/Cultures of Production, edited by Paul du Gay, 1–10. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 1997.

Farivar, Cyrus. “The NBA’s Ethnic Heritage Nights.” PRI, March 1, 2011. https://www.pri.org/stories/2011-03-01/nbas-ethnic-heritage-nights.

Halter, Marilyn. Shopping for Identity: The Marketing of Ethnicity. New York: Schocken Books, 2000.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991.

Koinoglou, Christina. “Greek Dancing from the Point of View of a [Millennial] Second Generation Greek American,” In their Own Words: OSU Students Write about Greek America, April 19, 2019. https://u.osu.edu/narratives/2019/04/19/greek-dancing-from-the-point-of-view-of-a-millennial-second-generation-greek-american/2018.

Leontis, Artemis. “The Intellectual in Greek America.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 23, no. 2 (1997): 85–109.

Leonard, David J. “A Fantasy in the Garden, a Fantasy America Wants to Believe: Jeremy Lin, the NBA and Race Culture.” In Race in American Sports: Essays, edited by James L. Conyers, Jr., 144–65. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2014.

Lillis, Ryan. “DoCo? SoBro? Kings New Branding of Downtown Commons Met with Praise, Mockery.” The Sacramento Bee, September 20, 2015. https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/news-columns-blogs/city-beat/article35853153.html.

Ritzer, George. Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption . Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press, 1999.

Morgan, Tiernan, and Lauren Purje, “An Illustrated Guide to Guy Debord’s ‘The Society of the Spectacle.’” HyperAllergic, August 10, 2016. https://hyperallergic.com/313435/an-illustrated-guide-to-guy-debords-the-society-of-the-spectacle/.