The Grace of Two Kings

by George Syrimis

In 1979, I read in some popular magazine about the death of a famous singer from Memphis who had died a couple of years before. And I wondered who this famous Egyptian singer I had never heard of before was. The same year I remember finding a key ring attached to a little plastic medallion with the face of black man on one side and the phrase “I have a dream” on the other. Being an avid ABBA fan, I kept the key ring because their latest album featured a song by the same title. I was young, and innocent, and ignorant then.

Twenty years later I found myself in Memphis, not Egypt but Tennessee, with a dear friend of mine. The city boasts of two kings and has named two boulevards after them: The Elvis Presley boulevard and the Martin Luther King boulevard. By then I was not as young, or innocent, or ignorant. But I still had lessons to learn.

To enter Elvis’s Graceland visitors first have to stand for a photo in front of a life size painting of the estate’s gates across the street. This staged faux “I-was-there” souvenir was the first of a series of vacuous experiences that was the Elvis Presley museum. The house is lavishly decorated, with theme rooms whose only memory is the ostentatious posturing and gratuitous extravagance only surpassed perhaps by Michael Jackson’s Neverland. The pitch of Graceland and Neverland at kitsch was commensurate with their owner’s fame. As the homes of two quintessential icons of the American dream—both of them kings of their genres—their material opulence evoked the hollow loneliness of Citizen Kane. The homes of two of the most celebrated citizens of an exclusive and coveted celebrity elite and their almost Messianic names never inspired much grace. Instead, a lingering sadness was the overwhelming emotion I felt standing with the rest of the visitors in the long line that passed in front of Elvis’s tomb. The religious aura was palpable. As with all saints, Elvis was a complicated one. The museum was packed with pilgrims. But it lacked redemption.

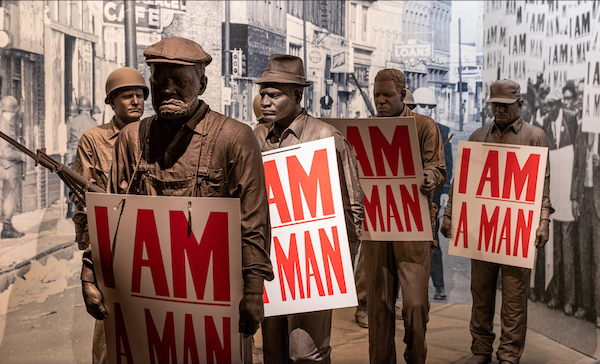

The crowd was significantly thinner at our next stop, a humble motel nine miles away, and now the National Civil Rights Museum at Lorraine Motel. The museum’s entrance was as unassuming as its preserved façade. Its inside, however, was as impressive as it was heart wrenching. Entirely gutted into one unified space, the museum’s design forces the visitor to follow a predetermined and chronological path through reconstructions of the most pivotal moments of the Civil Rights Movement. There was an original lunch counter where black students stood up to racism by sitting down, a bombed school bus, a jail cell in which visitors can hear Martin Luther King reading a portion of his Letter from a Birmingham Jail while the text appears on the cell wall. Just like Graceland’s painted gates most of these landmarks were also strictly speaking fake. But the sentiment was real. Each stop on the way towards the fated exit was a step into an emotional space haunted by living spirits and by a sense of guilt and shame mixed with pride and hope at the profound simplicity of a placard sign saying “I am a Man.”

There was something forced about the walking timeline in this museum, as if to stress the point that history is not to be avoided or silenced. To exit the museum, I had to walk like everybody else through room 306 and out onto the veranda where bullets shot through a king’s body but left his dream intact. Never had I been to a piece of land that carried so much grace. I had tears in my eyes as I stepped onto the veranda. But by then I was a changed man. The second time I was teary over something so political was when a black man was elected president of the United States.

Elvis Presley reached his own true Graceland a few months after Dr. Martin Luther King’s death in what was his ultimate home of redemption: a song with the title “If I can dream.”

George Syrimis

is the director of the

Hellenic Studies Program at Yale University where he teaches courses in

Comparative Literature and modern Greek culture.