Aubrey Dawne Edwards, Artist, Educator, Storyteller, Advocate for Social Justice: An Interview

Martin Luther King Day, January 16, 2023

by Artemis Leontis

Aubrey Dawne Edwards joined me in conversation on January 16, 2023, the 40th annual Martin Luther King national holiday. The conversation is an apt celebration of this important day. Edwards is an inspiring multimedia artist, educator, and storyteller and advocate for social justice. She is also a Greek American. She started out as a photographer. Her clients have included BBC, Comedy Central Fender Guitars, the Grammys, HBO, Nike, Playboy, The United Nations, Time, Volcom Entertainment, Fender Guitars, The New Yorker, New York Magazine, and her subjects have been published in magazines, newspapers, and ad campaigns, and shown in galleries. This just touches the surface. In the past decade, she has moved from freelance photography to community arts-based projects. The projects enter into spaces where violence has taken place and where communities of survivors are keeping memory of the destruction and also communal resistance. Images and stories are filled with landscapes, nature, people, animals, and history. The emotions are rich and complex.

Interview (Questions by Artemis Leontis)

Aubrey Edwards, a huge welcome and thank you for talking to me. How do you describe what you do?

Thanks so much for spending time with me. I wear a lot of hats, as they say. In a broad stroke, my work intersects the academic, artistic, applied and public spheres. I’m an arts educator and youth advocate. I’m a public anthropologist and historical archaeologist. I’m a mapmaker and a naturalist. I’m a storyteller and visual artist. I have formal training in journalism, photography, urban studies, applied anthropology, and community archaeology. Undergirding all of this, I’m deeply creative. These interests—and my values—ground the visual artwork I make. So, to answer your question, I make things. I make things that are often grounded in research, community collaboration, connection to landscape, and accessibility.

Social justice, labor justice, and racial justice are all important themes in your work. What has Martin Luther King’s legacy meant to you?

There are so many legacies to honor in this country. In general, I’m very interested in narrative and public memory, who and what do we remember and why? I have visited many landscapes connected to the good Dr. King—the Clayborn Temple that was the organizing headquarters for the historic sanitation strike, the Lorraine motel where he was assassinated, and most recently Marquette Park on the Southwest Side of Chicago. This park has an incredibly violent and racist history, known as the home to American Nazis in the 1960s. This landscape bore witness to many rallies, protests, counter protests, acts of violence, and acts of resistance. When Dr. King joined a fair housing march in Marquette on August 5, 1966, he was met by hundreds of racist, white protesters. They hurled rocks, hitting him and bringing him to his knees. He told reporters afterward, "I've been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen—even in Mississippi and Alabama—mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I've seen here in Chicago. "I visited this park this past December, it is a much different place now, and the Southside of Chicago has changed significantly since 1966. I photographed, and honored what had transpired on that landscape. So, this MLK day I will be sitting with the images, and creating pigment transfers—a process of color printing on transparent material that is transferred onto printmaking paper through an alcohol based gel. I’ll be working with my images, layering them with archival images highlighting the history of that landscape. And, of course, I always listen to the good Dr.’s speeches on his day.

I came to know your work through an image of the Ludlow Labor Massacre in Ludlow, Colorado 1914—part of your major series Tracing an Atrocity. In my experience, few people know about the Ludlow Massacre or its Greek hero, Louis Tikas. I’ve asked American neighbors who care about labor history, and I’ve also asked Greek Americans. Practically no one knows about the Colorado Coalfield War and Ludlow Massacre. How did you come upon it?

From the series, Tracing an Atrocity, 2021.

I first learned about Ludlow on the island of Syros, Greece less than 10 years ago. I was smoking cigarettes with the hotel owner, an incredible self-proclaimed anarchist who was incredible at the art of conversation. We were talking about American history and she asked me bluntly “Why don’t you all know about the Ludlow massacre? Why don’t they teach you in school?” That was the first I had heard about Ludlow. It’s buried in history, which begs the question of why it’s buried and why it is not more prominent in collective memory. Against the backdrop of the massacre, Ludlow was also a story of solidarity, organizing, and resistance across racial and ethnic lines. Those stories of solidarity are powerful, and dangerous in American narrative, right? We see many other examples of these stories being omitted from history and memory: the Battle of Blair Mountain in West Virginia has similar themes, and many local folks are working to bring that back into public memory.

Yes, some Greeks in Greece know American labor history better than Americans do, but it looks like you are ahead of the curve! So, Ludlow has struck a deep chord with you?

Ludlow is one of the reasons I decided to study historical archaeology (the period of time post-contact/colonization). A group of archaeologists worked on a collaborative and interdisciplinary memory keeping interpretation project at the Ludlow site. They partnered with descendants, the United Mine Workers of America, and community members to do archaeology on site to use material culture to better tell the story of who was there, and what their daily lives were like. The philosophy and values underpinning the Colorado Coal Field War Project have been incredibly inspirational to me. The field of archaeology is problematic in many ways (I won’t go into this too much here, just rewatch Indiana Jones), but the folks doing archaeology in Ludlow were focusing on being in service to the community, using material culture to affirm lived experiences, and inviting the public to be a part of the process. This interdisciplinary and collaborative community model has imbued my research and my work.

I can imagine how powerfully you would respond to Ludlow artifacts. Have you seen any of them?

I just tracked down the repository where the archaeological artifacts from Ludlow are housed in Colorado Springs. I have an appointment to sit with those artifacts in February. The material culture from Ludlow differs from many other excavation sites, it wasn’t trash. Archaeology is rooted in trash, what people throw away. The material culture of Ludlow comprises daily objects as well as precious objects folks left behind as they fled in a hurry amid the fire and bullets. I can only imagine how powerful these objects will be. I visit the sacred land of Ludlow a couple times a year, there will be a large creative project centering that story and those people, I’m just patiently waiting for it to unfold.

You are Greek American. What is your family’s immigration story?

My family’s immigration story is rooted in mystery. I know little things, small pieces to a bigger and grander story that I have tried desperately to uncover. And I am still trying. I spend a lot of time reflecting on ancestors and blood lines. I often talk to my ancestors, acknowledging and honoring them, not knowing their names or lived experiences.

My mother, Joanne, was Greek American. She grew up in the Southern California Inland Empire, where orange groves led into canyons and desert. Her parents, my Nana (Malpa) and Papoo (George), relocated there from the East Coast, perhaps in the 1940s. Their respective parents emigrated from Greece.

Year and photographer unknown.

This is where the story ends. My mother’s family endured a deep, and common “Americanization” process. Changing last names to pass, limiting the amount of Greek that was spoken in the home, abandoning (or hiding) traditional practices and rituals. They worked hard to be American, which now leaves me doing the detective work to find small clues here and there to tell me more about their story and where they came from.

Didn’t your mother or another relative share any part of their Greek story? What missing pieces of your family story have you been able to trace? What missing piece would you most like to discover?

My mother died when I was six, a horrible and prolonged battle with breast cancer that she ultimately lost in 1986.

Year approximately 1984, photographer unknown.

My Papoo had died the previous year, and my Nana would die a few years after my mother—after suffering several traumatic strokes that left her mostly nonverbal. As I grew older and wanted to learn more about my ancestors, any inquiries I had, any questions about where our people came from, there was no one to ask. My father didn’t know the answers or connections. I tracked down one of my Papoo’s sisters, who was still alive in the early 2000’s. “What was your last name, before it was Americanized?” I urgently asked her, hoping to cross reference Ellis Island ship manifests. “I don’t know,” she told me, “our parents never told us.”

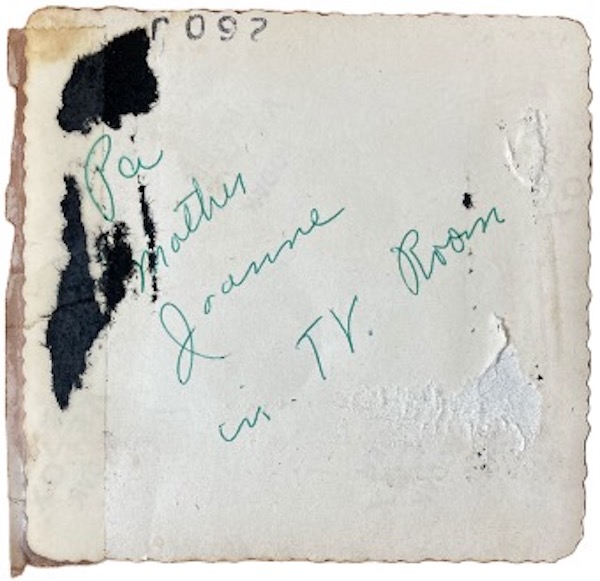

I have a beautiful photo, black and white, approximately 2.5x2.5” square image. My mother is about five years old, laughing while sitting on her grandfather's lap. Her grandmother, my Nana’s mother, sat next to her with arms crossed. Patterned wallpaper behind them. It’s the only photo I have of my maternal great grandparents, I have no photos of my paternal great grandparents. It’s matted, and rests in an ornate wooden frame.

Malpa’s parents, with my mother Joanne.

I ripped off the paper on the back, hoping to find names written on the back of the photograph, hopefully a date. It simply reads: Pa, Mother, Joanne in TV Room.

I wished there was more information as to who they were.

You’ve spoken on The Moth Radio Hour! I’ve listened to your story, “Grandmothers: Malpa and Myrtle,” about growing up in a home that restricted your creativity. How did you experience the restriction?

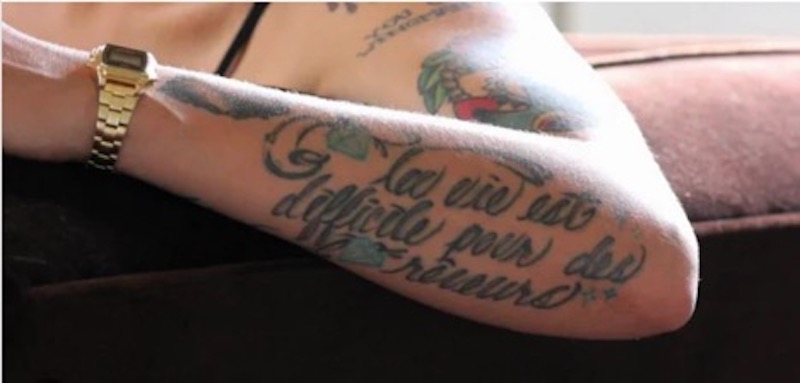

I grew up in an evangelical household, a religion called Seventh Day Adventism. The dogma was quite restrictive, prohibiting: eating meat, wearing jewelry, dancing, and watching television on the Saturday sabbath. As in any religion, there are more nuances and layers to the ideology, but these are the constrictive elements that I remember from my childhood. I was a wilding as a kid, I still am. Those rules didn’t work for me. I wanted to dance, I wanted to dress like Madonna with bracelets up my arm and T-shirts cut off my shoulder (this was 1985). I often got in trouble at our private Christian school for “acting out.” I have one vivid memory of cutting my shirt up in the bathroom so it slung under my collar bones. I was immediately sent home. That restriction laid the groundwork for how I have chosen to live my life. Unapologetically while constantly seeking out new life experiences and new ways of thinking.

What role did your grandmothers play in creating a sanctuary for your wild spirit. What difference did their involvement in your childhood make? How do you remember each of them—your Greek Nana Malpa and Grandmother Myrtle. What inspiration do you draw from these women?

Both of my grandmothers had been wild women, in their own right, in their younger years. Malpa broke accepted norms by divorcing her first husband that beat her, Myrtle used to box in underground fights to support her children as a single mother. They taught me to live my life without apology, through experience, and to create compassionate space in the process.

Highland, California, 1982.

I simply can't imagine my childhood without them. Coming from an evangelical family, they created space for me to be ... free. To be the wildling I was. Each one of them would tell me, “Now don’t tell your parents [what you do here].” I would never. I wanted to wear bikinis, dance around the house, wear lipstick, listen to Prince, and run feral. Their respective homes were a respite, a sanctuary. I miss both of them dearly, and am so grateful for them. Like the rest of my family origin story, I wish I knew so much more about them. Their layers and their memories. While I don’t know that, I do know how they made me feel. That, sometimes, is enough.

You left home when you were 15. Why? What were the conditions of your leaving? How did you complete your growing up process under the difficult conditions?

I often talk about my decision to leave home at a young age, while trauma does not define young people, my decision to leave and regain agency is a big part of my personal “origin” story. After my mother died, my father immediately remarried a woman who was incredibly abusive towards me. He also became an unbearable alcoholic. In my early teens, I adopted the punk ethos and became a skateboarder, I created a crucial community outside of my home. This community also informed my values. My father was a right wing, racist and homophobic police officer. To say our values did not align would be a severe understatement. In 1995, they had left our home in Redlands, California and relocated to a small desert town in Arizona. I lasted one year out there, packed up my things and caught a ride back to Redlands where I finished high school as my own guardian while living in a two bedroom apartment with six other skateboarders. Believe it or not, I got straight A’s. I chose to “divorce” my biological family, and create my own logical family, I am grateful I had the courage to do so.

Incredible that you found a supportive community so well aligned with yourself! What role did photography play in your youth.

Through this journey, I always had a camera. In high school it was a 110 film camera, I have photo albums full of images from this period of my life. Later, when I finished high school, I cashed in my meager life insurance policy to buy a Canon AE1 35mm film camera. This was the camera my mother had, she had been an avid photographer. Unfortunately my father threw out all of her belongings when she died, including all of her photographs and photography equipment. I came across several boxes of color slide carousels that survived the purge after her death. I scanned them in, and sit with them now and again. They were all taken before she got sick, before the alcoholism and abuse. It’s a period of my life I don’t remember, but it’s such a joy to look through her eyes to see this life and this love.

This is a good place to look at the trajectory of your work. When did you receive your first camera?

When my mother died, my father bought me and my sister a polaroid camera. I think it was meant to distract us, to give us something to do while he went through the post-death process. That, for me, was therapy. It brought me joy, it connected me with the world in new ways, it trained my eye to be observant, and it encouraged me to explore and be adventurous. Having a decades-long relationship with photography requires continuous negotiations and reevaluation of relationships with the craft. Especially as the craft has changed so much in my lifetime. When I went to photo school, we used color and black and white dark rooms, there were no digital cameras yet and certainly no cell phones! My work continues to evolve, as it should.

And the freelancing? That’s really intense work, especially music photography. Where did you start and how did your goals shift?

In my early days as a freelancer, my main goal was to have my music photography showcased in Rolling Stone magazine. An admirable goal! Now, my goals are to do right by the communities that I’m photographing, while creating visual documents of cross-cultural connection and celebration.

So in 2011 you formed an ensemble of three women photographers—with Ariya Martin and Elena Ricci—living and working together in New Orleans in galleries and other locations. Over time you turned to writing grants to pursue projects that were not tied to advertising or selling a person or product. Some of the new work you describe as community anthropology, and it has taken you into communities around the world. What is a standout project?

I’ve had the privilege of photographing so many incredible communities. For the project No Comply, I spent a couple years in New Orleans photographing an incredible culture of young Black skateboarders, many of whom began skateboarding after Hurricane Katrina. Schools were closed, minimal resources for young folks, there were concrete foundations where buildings had previously stood, and Walmart had skateboards for $20. They began skateboarding. I spent every week photographing, and listening to, young people. The pride they held when they landed a trick, the community they created where they felt safe and supported.

From the series No Comply, 2015.

This work, and their oral histories, were helpful in supporting the development of New Orleans’ first public skatepark. A youth-led space where young folks could be young folks and create their own logical family. The project name is a double entendre. “No comply” is the name of a skateboard trick as well as a nod to the refusal of young Black men in New Orleans to fall into a stereotype, rather building their own community and having agency over their own narrative.

How is your work evolving now?

Again, I am interested in narrative and story. Who is left out of our dominant narratives? How can my work serve as an entry point to access buried stories and experiences? I recently completed a years-long project in conjunction with the Anthracite Heritage Museum in Pennsylvania and with historical archaeologist Paul Shackel. Through Paul’s interviews and my videography and photography, we created an online exhibition for the cultural heritage museum that expands the narrative of who lives in this region, and who has made a life in this region. The dominant history centers on European immigrants, folks that came over to work with coal at the turn on of the 19th century, and whose descendants continue to live in the region. Our project, We Are Anthracite, centers the voices and lived experiences of the Latinx community members who began immigrating to the area in the 1980s. We worked to connect the immigration narratives—then and now—and tether the similarities between the two emigrating groups, such as racism and unsafe labor conditions. This work is underpinned by compassion and empathy, values that continue to inform my work.

Traces of the older Eastern European immigrant population

layered with traces of the newer Latinx population.

From the community project We Are Anthracite.

I imagine your experiences as a child losing your mother, witnessing the change in your father, suddenly having a stepmother and enduring extreme parental restrictions, and putting up a resistance are connected to your work as an artist and, youth educator. Could you identify some of the connections?

This year marks the 25th year that I have worked with young people in high schools, which is crazy! I started substitute teaching in high schools when I was 18, and have continued to teach art and media-based work to young folks for over two decades. I understand the healing power of the arts, especially photography. It is such a joy to see some of my past students thriving as freelance photographers and running their own businesses now. One of my favorite young people I have worked with over the years, Brad, photographed my wedding. It was amazing. I still remember the first day he came to my afterschool photo program in New Orleans East when he was 14.

And youth advocacy?

I would say the biggest connection from my past to my present is my service in youth advocacy. I identify as a youth advocate first, and an arts educator second. When I was young, I didn’t have adults I could trust or adults that had my best interest in mind. Because of that, I have chosen to be in service to young people through an advocacy role. It is humbling and honorable work, and I am always blown away by the brilliance of young people.

I just finished a pilot program here in Wyoming at Laramie High School, the Youth Justice Institute. Wyoming, a rural state of just over 500,000 people, it unfortunately has the highest rate of suicide and incarceration among young people. I cofounded this institute with investigative journalist Tennessee Watson, so young folks could explore and interrogate the state’s juvenile “justice” system as well as map supportive resources in their community. A group of 23 high schoolers met with adult advocates and allies on a weekly basis, being in conversation about issues that affect them as young people. They engaged with policy makers, social workers, public defenders, social justice activists, and restorative justice practitioners. They created time and space to reflect on what they learned through artmaking, and will be sharing out with their community through a public event at the University of Wyoming Art Museum in February. There is a huge need for youth programming in my community, so I have more programs unfolding in 2023!

What about your work attends to women’s experiences, and particularly women’s struggling to have a voice, to be a person, to tell their story, to be remembered, and to bear witness to history? Could you tell us about the Stewards project?

I really loved this project. I began this oral history and portrait project in the early aftermath of the 2016 election. The only thing I wanted to do was simply listen to women. I was living in New Orleans at the time, and started seeking out women who created and tended to intentional space. The 40+ women spanned across so many different disciplines and fields. A tattoo artist that works on trans community members, a restorative justice practitioner that holds space for juvenile offenders, a Unitarian minister who sits next to the dying—to name a few. I simply wanted to listen. I transcribed those oral histories, and presented their words in a book alongside a portrait of each steward. We had a beautiful community event and book launch where participants shared their experiences with the crowd. It was really lovely. That book lives in 20+ zine libraries nationwide. The final page of the book reads: For my grandmothers—Malpa and Myrle—who loved listening.

How do you leverage the knowledge that your great grandparents were Greek immigrants? I’m thinking of what you know and all that you don’t know. Is this knowledge interwoven in your work?

This is an interesting question. So much of my life narrative has been grounded in trauma, loss, disconnection, a void of knowing. I’m actively reframing that. There has been a shift in my understanding of my own experience. Sure, it was traumatic, however I held a great amount of resiliency. And, I’m actively reframing that thinking through the work I am doing researching the Greek experience in the American West. I have come to terms with the fact that I will not be able to trace my roots back generations, I won’t be able to visit the town or region in Greece that my people came from. But, what can I do? How can I reestablish a connection and celebrate my ancestry and blood line? For me, that comes through research and creative work. This is why I continue to visit that sacred landscape of Ludlow again and again. The resistance to oppression that was enacted here, the resilience that was embodied. It’s so moving.

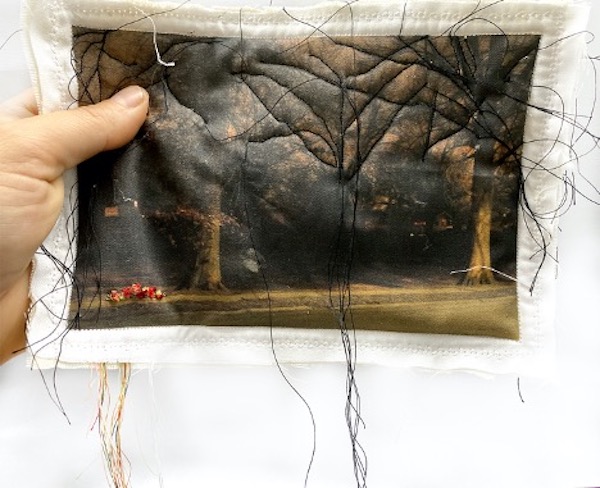

We talked earlier about the image of the Ludlow Labor Massacre in Ludlow, Colorado 1914—how this was my entry point into your work. Can we return to it? It’s one of 15 hand sewn and embroidered or machine shown photo printed pieces of cotton that comprise your project, Tracing an Atrocity , made in 2020. “Ludlow Labor Massacre” is on a rectangular, earth toned piece of cloth. A dark brown, bumpy horizontal line cuts across it like a river running through a landscape. A green stem and the red leaves of a carnation emerge from the dark brown line. What atrocity does it record?

When you visit Ludlow, there is a gate in the dirt that you can lift to walk down a short flight of stairs into a small concrete room.

During the “conflict” this was the site of the pit that was underneath a striker’s tent, records note that four women and 11 children hid in this pit. They were trapped, the national guard/state militia set the tent on fire, and two of those women and all of those children suffocated and died. Now, violent labor strikes and labor-rooted massacres were not an anomaly during this period of time in America, they were quite common. What set this violence, and this massacre, apart and made it more appalling to the public, was that women and children were murdered.

Where did this Ludlow image come from? How did you select it?

The sewn image is of the pit at Ludlow where two women and 11 children

suffocated.

This image is of that pit-turned-memorial. Every time I visit Ludlow, I find and experience new objects of remembrance and offerings that visitors have left behind. There is an ever-accruing collection of national union stickers on fence posts you enter through, and there are often toys and knickknacks laid on the feet of the granite memorial. This was the first and only time I’ve seen an offering left in the pit. It was just beautiful.

Can we think a little more about your use of sewing to trace the images of atrocity? When I see a hand-sewn textile, I think of women’s work. My Greek grandmothers were making things with needles and thread all the time. They embroidered, crocheted, darned, and sewed. They liked the work because it was often communal—they did it with their women friends—and it wasn’t a paid, commodified service. Immigrant women in the textile industries sewed for long hours for little pay. When I see this piece of cloth, I think of immigrant women’s work.

I really love this connection, especially given my deep interest in labor and the crucial immigrant labor that built this country. I’ve sewed my whole life. My Nana had her sewing machine set up prominently in the dining room, and I have vivid memories of going through all of the drawers that held colorful pieces of cloth, arrays of bobbins, and tattered patterns from the 70s. Through the process of renegotiating my relationship with photography, I wanted to start printing on something that was tangible, meant to be held. I am interested in that creative connection between the brain, hands, and heart. For me, sewing is also an incredibly meditative experience.

How did Tracing an Atrocity turn into a sewing project? What does it signify for you? What would you like people to be able to do with this sewn piece of cloth?

I have a massive cache of images that I have shot on landscapes of atrocity, and landscapes of resistance. I have spent a lot of time on American interstates and highways, and I stop at a lot at sites of conscience. I wanted to spend more intimate time with these images and these places, so I began printing them on fabric. From there, I would hold that place, and meditate on that place through sewing. I recently showed a piece at a group exhibition. It is the site in Ferguson, Missouri where police officer Darren Wilson murdered Michael Brown. There were specific directions posted next to the podium that the piece sat on. “Please hold.” Hold the work, feel the work, and connect with this place and what has happened here.

in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014.

From the series Tracing an Atrocity, 2019.

Is there something more you would like to explore of the Greek American past?

Part of my current research is exploring community creation during westward expansion, through the lens of immigrant labor. I’m curious, how did Greek people take care of each other in these new landscapes they immigrated to? How did they hold traditions and ritual in the company town? What values did they carry with them, from the old world to the new? There is such a rich history of Greek heritage and lived experience in the west. For now, Ludlow is my starting point. Again, incredibly excited to spend time and hold space with the archaeological artifacts. These objects will shed light on what they brought with them, what they carried, what they treasured. I’m getting chills in anticipation.

When you started to take pictures, what expectations did you bring to the work of making photography? Looking back at your trajectory, have you been fulfilling a vision or giving shape to your role as artist as you went along?

When I first began taking pictures, I wanted to see the world in a new way, I wanted to capture moments and I wanted to financially support myself through my photography. That has evolved in tandem with my own growth as a human being. I believe in expansion and exploration, in all that I do. And now, I don’t want to commodify something I have had a lifelong love affair with. I quit freelancing a few years back, which has deepened my relationship with photography. I used to call myself a photographer, it took me a very long time to identify as a visual artist. I am, obviously, an active participant in my own life, but in some sense, I am also along for the ride. I am here as creativity and ideas unfold in the most unexpected ways. How life continues to surprise you, while simultaneously affirming that you are indeed on the right track. It is impossible for me to not make things, to not learn, to not listen. I think of the scorpion in the Aesop fable, this is my nature.

What step do you dream of taking next?

The only step I dream of next is seeing what unfolds. How can I continue to bring my values into my work, and how can I continue to expand in thought and practice?

Aubrey, it’s been a joy. I’ve seen, felt, and learned a lot! May you keep moving forward. What were Martin Luther King’s words? “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.”

Aubrey Dawne Edwards is a veteran photographer, collaborative anthropologist, storyteller, researcher, mapmaker, naturalist, and educator. She holds an Associate of Applied Science in Photography (ACC), Bachelor of Journalism (UT), and a MS in Urban Studies (UNO). She is presently completing an MA in Anthropology and Environment and Natural Resources with a focus on community archaeology at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. She works across the academic, creative, applied, and public spheres. She has a long list of editorial and commercial photography clients and has received numerous grants and residencies, exhibited nationally and internationally, and taught visual art to learners ages 6-70 years old. Research interests include: the archaeology of capitalism and wage work, collectivism and socialism on the Western frontier, and interdisciplinary, community-rooted memory keeping practices on landscapes of labor, organizing and white supremacist violence. She uses her background in collaborative anthropology to connect organizations, policy makers, artists and teachers in jointly amplifying youth voice. One current project is listening to workers in Southwest Wyoming and Northeast Pennsylvania, documenting voices around changing labor environments in historically coal-centered economies. Another is working in conjunction with Partners For Rural Impact, leading a cohort of young folks as they use art and media making to dissect and disrupt the narrative of what it means to be “rural.” She is the cofounder of the annual Youth Justice Institute where young folks can learn about their rights while making public art and media, centering their voices in conversations around juvenile justice reform in Wyoming.

Artemis Leontis is C. P. Cavafy Professor of Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan. She teaches and researches Greek language, literature, and culture. Her most recent book is Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2019, Pataki Publishers 2021).