Anna Tsouhlarakis, Multimedia Artist

An assistant professor in the department of Art and Art History at the University of Colorado, Boulder (MFA Yale University), Anna Tsouhlarakis works in sculpture, installation, video, and performance. She has participated in various art residencies and been part of national and international exhibitions at venues such as Rush Arts in New York, the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Art Mur in Montreal, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Crystal Bridges Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, the Heard Museum, NEON in Athens, Greece, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Tsouhlarakis is Greek and Creek, and an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation.

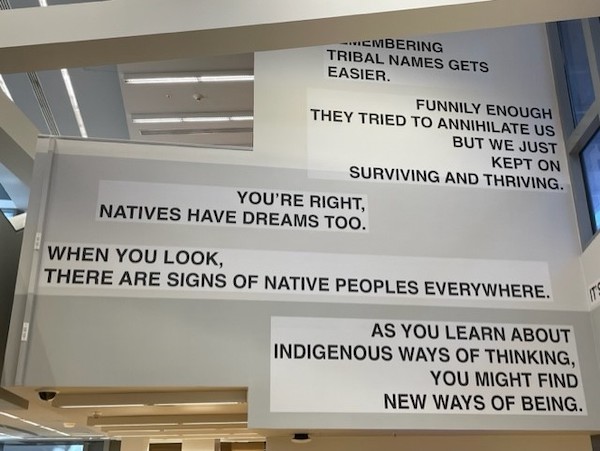

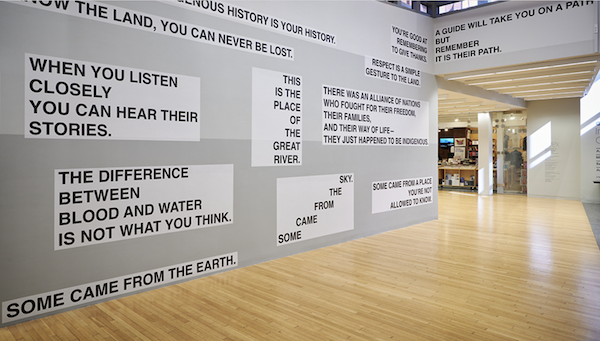

I first came across her work in the context of the Native Guide Project: Columbus, an exhibit at the Wexner Center at the Ohio State University, which deploys boldface phrases such as “I LIKE HOW YOU SEE NATIVE AMERICANS AS YOUR INTELLECTUAL EQUAL.”

“Framed as responses to a potential interlocutor, Tsouhlarakis’s texts encourage viewers to question their complicity in the ongoing erasure and displacement of Indigenous tribes. The work references the more than 10,000 earthworks across Ohio built by Native people long before the arrival of settler-colonists.”

Interview (Questions by Yiorgos Anagnostou)

Would you share with us the major contours of your artistic vision and mission?

In my work I am interested in challenging and stretching the boundaries of aesthetic and conceptual expectations to reclaim and rewrite Native definitions of making through video, performance, sculpture, photography, and installation. Using Indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies as starting points, I work to reframe the discourse around the construction of Native American identity.

What is a couple of examples of your art contributing to your politics?

My text work began with the original Native Guide Project in Colorado Springs, CO. It consisted of two billboards placed around the city as well as profiles on social media that had 23 different versions of the text work. In several of these pieces, I speak about Native rights and sovereignty.

Another example is my most recent exhibition that opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver, Indigenous Absurdities. It’s a solo exhibition consisting of six sculptures, six large scale collages, and a 5-minute video installation. The focus of this body of work is Indigenous humor but I take on topics including feminist issues and bodily rights.

Your last name connects with Greek heritage. What is your family’s Greek connection? What is the story?

I am Navajo and Greek. My grandfather came from Crete to the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. He traveled throughout the United States and finally settled in Gallup, NM, in his fifties, where he opened a diner called the Coney Island. There he met my grandmother who was Navajo. She was a waitress. They soon married and had two children, a boy and girl. My grandfather died when my father was around 12 years old. When my grandfather passed away in the early 1960s, the two sides of our family lost connection because our American family did not speak Greek and my Greek family did not speak English.

In 1998, I became the first member of my American family to travel back to Greece to meet our family in Chania.

In college, I learned a bit of Greek and traveled to Italy for a study abroad summer. Before I went to Italy, I was in New York and met up with someone I found in the phone book, another Τσουχλαρακις, and the only one outside of our immediate family that I had ever found in the US. We met and we assumed we were related because we both had the same last name and similar connections to Crete. He gave me a name and number of family in Athens.

After my studies in Italy that summer, I traveled to Athens. I met with this couple, and they then connected me with their family in a village in Crete. The family met me at the ferry in Souda and brought me back to their house. But it turned out, after much eating and talking, that they never had any family members immigrate to the US in the first half of the twentieth century. We looked in the phone book together, using the little information I had. They called several names that seemed to match my family’s stories. Finally, around the fifth attempt, they reached someone who answered and they described my American family. They asked if there was a George who had left for the United States in the early 1900s—did they know this relative? The answer was a definitive yes. Within the hour, I was driven to Chania and met the Greek half of my family, waiting for me. They welcomed me with open arms, many tears, and more love than I could have ever imagined. From that moment, I knew I was home.

Do you visit your family in Greece? What is the experience like? How do you feel being in your ancestral island but also broadly in Greece?

After my initial visit to Greece, I became fluent in Greek and traveled back every year. I became familiar with our extended family, village, house, and land. Now that I have three children, we continue to travel back so they can also know their family and land. They have been attending Greek School since they were all 3-years-old, so their knowledge of the language and culture is continually growing.

You have described yourself as a multiethnic native person who identifies as “fully Navajo and fully Greek.” What does each identification mean and how does it matter in your life? How is it expressed? Have there been any internal conflicts? Any intersections?

The first time I visited Greece I was a bit nervous. I didn’t know how I would be perceived, or if I would be accepted by my family. Nobody in my family had been back to Greece since my grandfather came over in the early 1900s and none of my Greek family had been to the States after my grandfather. I am a dark-skinned woman with black hair—my look is quintessentially Native. But when I first arrived, I was welcomed with open arms. My family told me that I may look American, but on the inside I’m Greek. I never forgot that. As I grew older, I learned more about Greek culture and learned it is a patriarchal society—Navajo is matriarchal. In these ways, I am both fully Navajo and fully Greek. I don’t divide myself into fractions.

One of the phrases in your Native Guide Project reads, IT’S NICE HOW YOU REALIZE INDIGENEOUS HISTORY IS YOUR HISTORY. How should this matter to European groups who entered the United States after the displacement and indignities suffered by the native peoples?

It does not matter when one becomes an American—whether by birth or other means—the history of this country is never obsolete. Everything in our society is built on what happened in our country in the past 400 years. From precontact, to contact with Europeans, to the revolution that defined the modern United States, to everything since. If we don’t know our past, how can we build a future? We learn from our mistakes, but if we don’t know about those mistakes, how can we plan for a better world?

Is there a place for Greek heritage in your art? What is the motivation and purpose for including it? Are there any elements in this heritage that align with your politics?

The voice within my art speaks to Indigenous identity and issues, but the strength of my voice is undoubtly Greek. I am the culmination of these two cultures coming together to create something new.

I see the influence of Greek art in my work, particularly in sculpture. There is a clarity of form and use of space in Greek sculpture that I incorporate in my current work. It’s subtle, but it is present.

You have participated in the exhibition Portals, in Athens, Greece. What piece did you chose to display? How did it feel to present your work in Athens?

The artwork I had in Portals were text pieces from an installation titled “Edges of the Ephemeral” (2012). The original installation was very large—about 20 feet in diameter. For the Portals exhibition, two aluminum signs from the original installation were shown. The text is about the loss of language and culture, basically the demise of a society. I had immense pride in being able to share my work in Athens. It was my first exhibition in Greece.

Along the lines of institutional and social recognition of Other cultures, are there any elements from your Greek heritage that you would promote for public recognition?

Since I first began making work as a professional artist, I have always been vocal about identifying myself as both Native American and Greek. I believe it’s incredibly important for me to continue to do so, especially as racial tension builds in the United States. As I get older I can see the influences of both sides of my heritage in myself and my children. They both are rich histories full of strength, determination, and resilience. I am just one piece of that complex story.

Your US indigenous heritage connects with a history of violent oppression and ongoing struggles for social justice and Native American rights. Your US Greek heritage connects with initial discrimination early in the twentieth century and eventual acceptance and incorporation. But we do not see European American groups often reflecting on their position vis-à-vis current Native American struggles. In what manner could European Americans contribute to Native American causes?

This question circles back to the importance of knowing your history. What is the story of the state you live in, the town, the street? What Native Americans lived in this area and where are they now? With the ease of access to media and amount of information we receive every day, ignorance is a choice. Of all people Greeks should remember their own history and what made our culture thrive and last through the millennia. Any place you go in Greece, especially when you’re with family, you’ll hear the stories and struggles of the land and people. Everyone learns those things and passes them on. There is no reason not to continue that in this country.

What is your idea of community? Do you interface with the Greek American community?

I don’t have a firm definition of community. I’ve lived many places and I am continually finding new ideas of what community is and can be. Sometimes it’s very tight knit and sometimes it’s looser.

In the late spring of 2020 we moved to Boulder, CO. It was the middle of the pandemic and my three children weren’t able to meet any new kids at their American school because it was all online. In the fall of that year my kids started at a new Greek School two days a week in Denver, in-person. This became the only outlet we had to seeing other families in person on a weekly basis for that first year we lived in Colorado.

There was a lot of masking and testing but they loved being able to go to a school and to be around other kids. I volunteered as much as I could and helped with the online auction that spring. At the end of the year, as I was picking my kids up after their last class, the director of the school knocked on my window and handed me a travel mug with my name on it to thank me for my volunteering. It was a small gesture of thanks but brought me to tears. It was a physical sign that I was a member of this community, a community that welcomed our family into this new state and helped us through the toughest parts of the pandemic.

What does success mean to you?

To be at peace with my choices. If I can look at what I have done and have no regrets, that is success to me.

July 13, 2023

Editor’s Note: Anna Tsouhlarakis often employs podcasts to reflect about her craft as an artist and its connections with her identity. For the most recent ones listen here, which includes a narrative about her “growing up in in a family of artists and her decision to pursue art as a full-time career.” Listen to Anna reflecting about her identities, her exhibition in Athens, and experiences in Greece here (“That’s who we are now. In 2021 that’s how many of us live, we have complex, contradictory identities. And that’s ok, it’s not easy, it’s not simple, [not] clean, it’s very messy…” [9:10-9:30΄]).