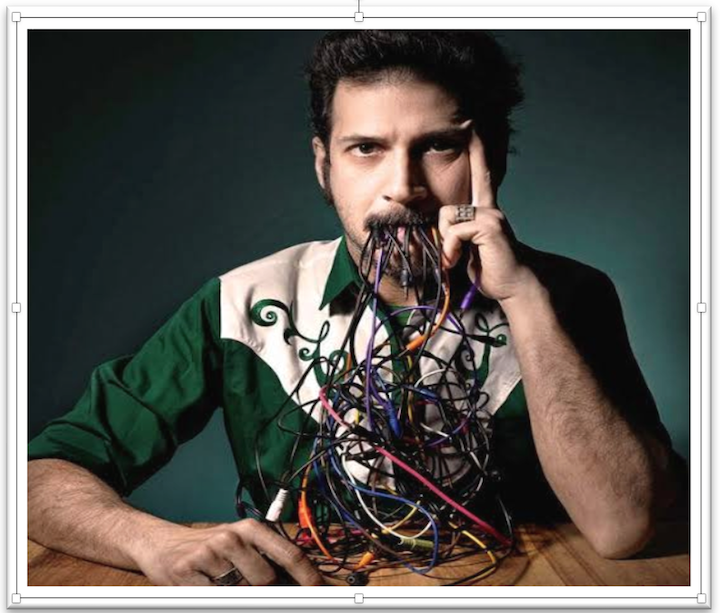

“Existing In Between”: An Interview with

Musician Tasos Stamou

Tasos Stamou is an electroacoustic music composer and performer, alternative electronic music instrument maker, tutor, and sound technologist based in London, UK. Predominantly a solo artist, Tasos also frequently collaborates with other experimental musicians including Mike Cooper, Thodoris Ziarkas, Anna Homler, and the London Improvisers Orchestra. He has performed across Europe and the U.S. including at major festivals and performance spaces for experimental music including the Incubate Festival, Café OTO in London, CologneOff Festival, and the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens.

His music is inspired by a variety of contemporary and traditional genres including free improvised music, musique concrète, noise, drone, Greek folk and rebetika. His compositional approach is intimately personal and includes elements of his immediate environment combined in novel ways with nostalgic memories of his childhood, and the loss of beloved relatives embodied in sound. Central to his work is the incorporation of old and new with special attention to traditional Greek music as well as the juxtaposition of acoustic and electronic sounds.

Interview (questions by Yona Stamatis)

Electroacoustic Music

Please introduce us to electroacoustic music.

TS: Electroacoustic music is a sophisticated musical style that emerged during the second half of the twentieth century. At its core is the incorporation of new electronic instruments including recording devices, synthesizers, and other new media. I consider electroacoustic music to be a continuation of the tradition of symphonic music composition as composers incorporate contemporary sounds and experiences, in particular those associated with new technologies and with life in the industrial world. Electroacoustic music is often identified by other terms like musique concrète and acousmatic music.

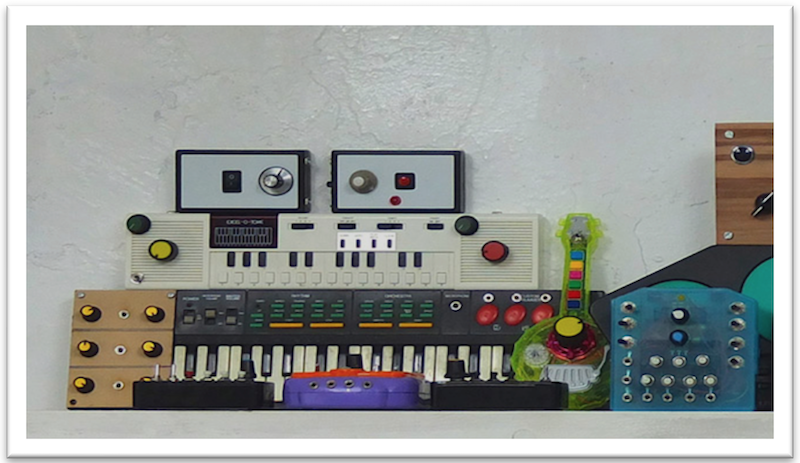

Your recordings and performances often rely on an electroacoustic studio. What is included in your studio?

TS: My electroacoustic studio includes a few elements: recording equipment on which I record the sounds that I am making; a computer where I compose and edit; some acoustic sound sources; and some electronic effects that allow me to me manipulate the sounds I am creating. At home I have a large and complex system and I also have miniature portable versions that allow me to compose and perform while I am traveling.

Solo at Madame Claude, Berlin, March 2015

I understand that you also create your own instruments?

TS: When I first began composing, I wanted to find my own brand new sound palate. In order to keep a certain distance from the instruments and techniques that I already knew, I began to create and repurpose various sound-making devices. For example, I found it very easy to work with vintage, battery-operated, electronic music toys: I would manipulate them and try to extract new sounds that I would then incorporate into my compositions. My aim was to create new sounds that had never been heard before, and to find a truly personalized sound. I also created new sounds by hacking electronics to create my own mini-synthesizers – and while I initially did this in order to surpass the cost of expensive synthesizer gear – eventually it became a passion. And so I founded a small brand and began selling gear to musicians. And then I began to host workshops to teach musicians how to create their own equipment.

Can you help us understand how we should listen to electroacoustic music that might not necessarily contain a melody, harmony, and lyrics?

TS: Above all, you must free your mind and listen closely. There are so many new and unexpected elements in these compositions that at first, it might be difficult to connect to the music: one is never sure of what is coming next and it might be difficult to grasp the atmosphere of any given piece. Instead, in electroacoustic music it is best to listen without expectations and to remain absolutely open to what might come. Simply listen carefully and to try to grasp various elements, so that you can begin to understand the very personal narrative within the music. This is why electroacoustic music is generally performed in an auditorium setting, which provides a context for people to sit quietly and to listen.

How do you characterize your compositional approach?

TS: I am very interested in the interplay of acoustic and electronic elements—in performing what I characterize as a slight magic trick: while I play an acoustic instrument, I transform the sounds so that they exist simultaneously in a more abstract electronic format as well. Or the reverse: I may play acoustic sounds and field recordings through speakers and simultaneously play an acoustic instrument that has been altered to create totally non-acoustic sounds. I am fascinated by this mix, by the sound world that is opened by combining acoustic and electronic music.

I am curious about what made you gravitate towards electroacoustic composition?

I am originally trained in the visual arts. I was a professional photographer until 15 years ago. I first began recording some experimental music at home when I was in my early twenties. I was very influenced by a show on Greek National Radio that would play electroacoustic music, and experimental, free improvised music late at night. And eventually I overcame my shyness and I began to share my work with other musicians who assured me of its value and encouraged me to release a recording.

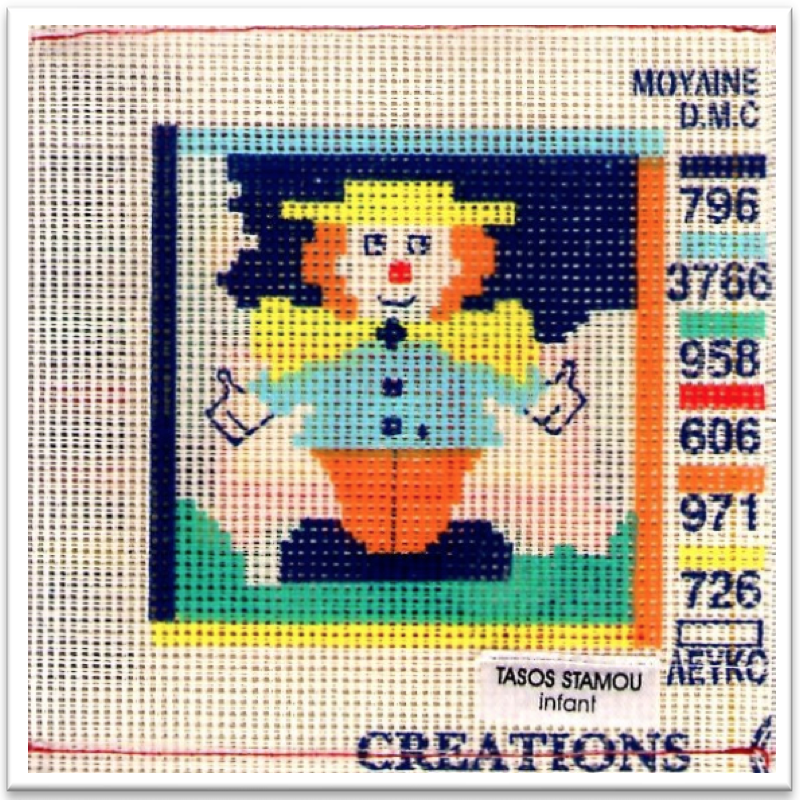

To this day, I am very pleased with the outcome, which was my first recording, The Infant album. I took it very seriously and it was truly a culmination of the many musical ideas I had up until that point. The music on the album is made entirely by toy instruments. This was a result of my great desire to move away from the sounds and techniques that I already knew and towards creating my own unique sound and structure in music composition. After this recording, I was completely empty of ideas, and I needed years of new experiences to start creating musical stories out of them.

At the same time, I began performing on stage as well. And I realized how much I loved playing for an audience. I loved the audience and the experience on stage. I just wanted to keep doing it.

Greece and Abroad

Is there a thriving scene in Greece for this kind of music?

TS: Yes, there are communities everywhere of people who love this kind of contemporary exploratory music. Especially in Thessaloniki I have met a lot of people involved in experimental music. Mostly in major Greek cities.

Was it music that inspired you to eventually leave Greece and move to London?

TS: No, it wasn’t. My ending up in London was somewhat accidental. In fact, I had been planning to leave Greece for Berlin or New York. I had been looking for a new environment in which to make music and to collaborate with others. But then I met someone who was getting ready to pursue her master’s in performing arts in London and she invited me to come along. So while I initially had not given London much thought, after living there for a couple of months, I realized that it was in fact a great musical environment filled with many opportunities for me.

Do you consider London a home for you now?

TS: Well, not exactly. I left London one year ago and now live in the English countryside. But I have amassed so many experiences and memories from the 11 years that I lived in London that of course it was a home for me. It is one of the places that I feel is “homelike.”

Can you describe your interaction with Greek communities in England?

TS: Where I live now in South Essex, I have only met one Greek guy and quite by chance. He is in his seventies and was thrilled to meet me. He thought he was the only Greek in town. So in a way, we are the Greek community, just he and I.

But to be honest with you, during my initial years in London, I did not want to interact with Greeks. All I wanted was to lose myself in something unknown. But after five or six years, I suddenly started craving interaction with Greeks. I don’t know how or why—it just happened. And so I began to seek out Greeks in London and started to interact with more Greek musicians. And I started traveling more often, visiting Greece more, and generally began to experience quite a profound nostalgia for Greece and for my past.

You have been away from Greece for more than a decade. How do you identify? Do you consider yourself a Greek in xenitia, or a diaspora Greek?

TS: I absolutely identify as a diaspora Greek and I am really happy about it. There is something about me that enjoys being somehow “in between,” not really here or there but slightly outside of every place that I go. It just matches my way of thinking about the world, to look at things from a slight distance. I enjoy this very much.

Would you ever consider returning to Greece?

TS: I have not seriously considered returning to Greece, but of course there are always thoughts in the back of my mind about what it would be like. Sometimes of course, I fantasize about returning. If the circumstances were ideal, I probably would return. But I think having this fantasy is more important than actually returning to Greece. The nostalgia is even more important than actually moving because it keeps me going and creating. As I said earlier, I am happy with my identity as Greek diaspora. I like this role. I really like it. So one of the problems if I return to Greece is that I will not be diaspora any more, and I just really love this title.

Can you help me understand why you like this title so much?

TS: I don’t know, it is just me. I feel it. It is the position that I best belong in, existing in between. I realized it coincides with how I see the world. It just works perfectly. Not identifying too much with any one thing, but still being there and here and there and everywhere. Kind of like this state in between.

The Greek Period

I think this perspective plays into your music quite a bit as well. I have noticed that there was a distinct change in your compositional style, around the year 2018, where you suddenly “go Greek” if you will.

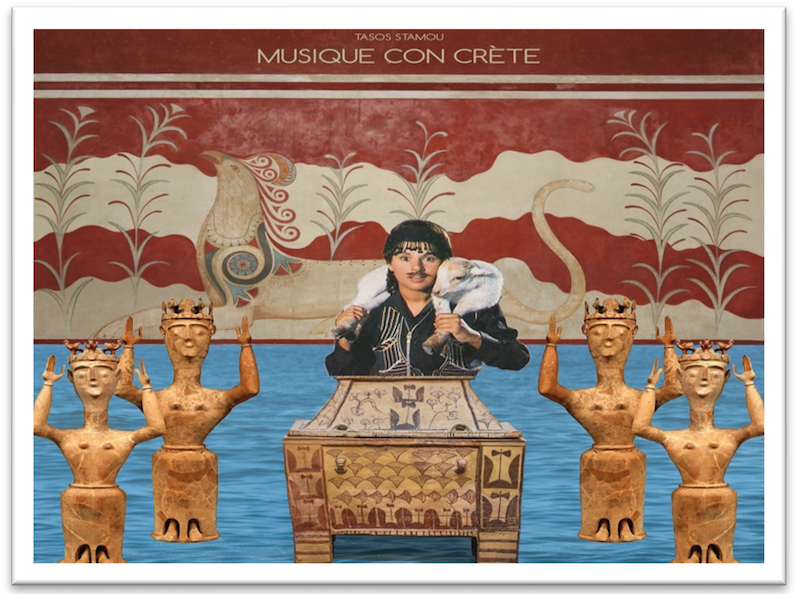

TS: Well, as I mentioned slightly earlier, after six or seven years in the UK, I suddenly started feeling extremely homesick. It was really very sudden and unexpected. Up until that point, I had felt anything but homesick. It is really hard to explain why or how it happened because it really was just emotional. So I began to travel to Greece more often and as I did, I began to collect musical material to bring back to England. I began buying Greek records and making field recordings of folk musicians. And I even did an artist’s residency on the island of Crete. From this residency emerged my first Greek-oriented album Musique con Crète, which was also my first album where I decisively began to work with raw materials drawn from my musical and cultural heritage. Prior to this album, audience members would often approach me and tell me that they could detect elements of southeastern Mediterranean music in my compositions. But it was always hard for me to understand this, and it had certainly not been my intention. But I truly enjoyed working with this acoustic musical language because it really connected the two different sides of me: the nostalgic part that longed for my past and for Greece, and the future that is in the changing contemporary world, in England, or wherever I may find myself.

“Vasiliki” from Musique con Crète

The title of the album is a brilliant pun. How did you come up with it?

TS: I am very happy with the album title too. To be honest, the idea just came to me. Maybe I only had this epiphany because I had just suffered a concussion! It’s a long story but to keep it short, I initially was supposed to go to Crete for an artist’s residency at a studio owned by a friend of mine. The studio is right by the sea and is housed in a space that used to be a famous tavern, in the fifties, where [Vassilis] Tsitsanis, [Markos] Vamvakaris and all the other rebetiko greats used to perform when they visited Crete. It is an extraordinary space, and it still has remnants of the old tavern, like the big old refrigerator. And it even has that tavern smell. Anyway, the idea was to engage the space in my artwork by creating sound sculptures. I had planned to work with objects that I found around Crete, like old barrels from the mountain, rotten branches from the woods, and so on. But then, one month before I was set to leave for Crete, I had an accident. I got a concussion and I broke my elbow which meant that I couldn’t use my right hand. Without use of my right hand, it would be difficult for me to create large sound sculptures. So I had to come up with a new idea for a project that was less hands on. And that is how I decided to begin doing field recordings. I planned to collect different sounds from around the island, to buy old recordings and so on, and to manipulate them to create something new and my own. And so, there I was in bed, and it suddenly occurred to me that what I am doing is musique concrète. Hence, the title Musique con Crète.

Who are your audiences? Who is purchasing and listening to your music? Is it predominantly Greeks?

TS: Musique con Crète went out through a label that already had its own audience. Both digitally and on vinyl. I am not sure who my other audiences are. I don’t think it includes many people that are into traditional folk music. My albums are not housed in the folk sections of record stores. They are mostly distributed online. The digital version of the album is fine of course, but there is a certain nostalgia about the vinyl medium that I like. Anyway, I assume my audiences are made up more of people who are into experimental and electroacoustic music.

Can you tell me about your other Greek-influenced albums, in particular the Aman trilogy?

TS: As I mentioned before, Musique con Crète was a turning point for me. In Musique con Crète I found my musical language. I use the term language because I see composition as similar to literature in the sense that my musical compositions are like sonic essays in the sense that there is a narrative and there is meaning to interpret. But it is also abstract which I imagine makes it closer to poetry or maybe to abstract literature.

So, I decided to continue working in this musical language and I created two more albums to form a trilogy of Greek-oriented albums: Musique con Crète and the two Aman albums. The Aman albums were inspired by rebetiko music because this is the music that I identify with the most, and I understand exactly what it is about. So this was a very personal project for me. Beyond the fact that I am posing on the back cover naked playing a bouzouki, there are many other very personal musical elements. For example, many of the field recordings that I use on the albums are of my uncles and me playing rebetika together in my yard, over the span of several drunken evenings. I also incorporate many songs that I used to listen to with my dad. In fact, the whole album, D-A-D is dedicated to my dad who had passed ten years before the record was released. D-A-D also refers to the tuning of the rebetiko bouzouki of course. So, the idea was to hack rebetika music like I hack everything else, but to offer a very personal lens.

Can you walk us through the compositional process of a specific song?

I have a great example to share. When I go to Greece, I stay in a house by the sea in my dad’s hometown. Once, as I was driving back to Athens, I was listening to a recording I had made the night before of me playing with my uncles. My idea was to hack the recording and use some bits and pieces and of course to manipulate the sounds. And as I was driving and listening to the record, suddenly the cd started to make strange electronic sounds. It must have been scratched and it started to jump and loop and the music suddenly became very experimental. I could still hear the songs, but it was scratchy and mixed up. I immediately took out my phone and put it next to the car speaker, and I recorded a 40-minute session of the cd getting mixed and looped in the car. And so that became a piece on the album. It became the track “I Don’t Want You Any More.” My work was done for me, by chance, in the car, by a scratched cd and my cell phone.

I am curious to learn more about your relationship with rebetiko in Greece and in England. I know that there is a big rebetiko scene in England and especially in London. Did you interact with any of those musicians?

TS: Well no, I did not. I never found a real connection with them. It’s a different atmosphere. It’s different. The only person with whom I collaborate in England who plays with some other rebetiko bands is my collaborator for the Aman Duo, Thodoris Ziarkas. He’s a double bass player. We actually met through our shared interest in free improvised music, and we became fast friends. And so, we formed the Aman Duo that was devoted to mixing our two shared passions, rebetiko and free improvisation. The initial idea behind the duo was to make music for both audiences: for those who like experimental, minimal, non-melodic, free-improvised music, and for those who just like rebetika. Our goal was for both crowds to like it. So it really was a musical experiment to see what the reaction would be. And we played in both kinds of venues as well, the concert hall and the more tavern/tekes [hashish den]-like context. We really were not sure what the reaction would be of Greeks that like traditional rebetika to our hacking rebetiko. But all of our experiences playing Greece and for Greek audiences in the UK were really good.

I will never forget the greatest gig of my life was with the Aman Duo, in Thessaloniki, shortly before the Covid lockdown. It was absolutely mental. It is hard for me to put into words what we accomplished. But the experience came very close to our original fantasy which was to somehow recreate the tekes atmosphere but in a contemporary way. We thought a lot about what kind of performance this should be and whether we wanted people to sit and listen quietly to our music, or to dance. Well, anyway, there we were, in a great big room, Thodoris and I, hacking rebetika live for a really diverse audience. There were young people, and older rebetiko fans, and punks. You would see older people dressed up in a slightly rebetiko way, and then younger people with hair dyed all different colors right next to them. I remember one moment where most everyone seemed to be quite nicely stoned, including us, and it became a really spiritual experience—spiritual in the rebetiko sense. It was almost hallucinatory to the point that I wasn’t sure if it was actually happening. It was just like a proper postmodern tekes. It was so weird. And it was exactly what we had wished for. It was one of a kind and we couldn’t believe it had actually happened.

Is there a main takeaway, or are there any final thoughts that you would like to share with us about yourself, your music, your feelings as a Greek in England, or anything else?

I’d like to mention that the reason behind this new Greek focus on my albums, is not national pride. I am not trying to make the statement that we Greeks are the best in the world. I think my intention is to engage in a kind of microscopic observation of the culture that I come from, and to use these observations as a tool to talk about issues that everyone can relate to. So, it is a means to engage my music and my art to talk about shared global issues, issues faced by all of humanity. Of course, the fact that Greece has such an extraordinary cultural heritage makes my life easier because there is so much material to draw from. And I really like incorporating the ancient into the modern and bridging this gap through my music.

Before we end, I must share a story with you about bridging ancient and modern in my music and the extraordinary cultural heritage that is still so vibrant in Greece today. While I was on Crete, I became good friends with a man who owned a restaurant. At the beginning of our friendship, he asked me if I could join him the next day to help him shear some sheep. Of course, I agreed. My girlfriend (who is now my wife) and I went there, and as soon as we arrived, I realized that this was not merely an experience of shearing sheep. I was suddenly part of a proper ancient Greek ceremony that happens once a year in Crete, especially in Southern Crete: the owner of sheep invites a very close circle of friends for an elaborate ceremony.

So, on this day, male goats were slaughtered first, in a very ceremonial way. When night came and the ceremony was finished, we ended up deep inside the forest at a huge table with an elaborately prepared meal. And then everyone started singing this almost ancient sung poetry, improvised poetry, while drinking this ancient wine they had stored in barrels. It was surreal. It was mental. I didn’t know about this custom but apparently they do it every year, and this custom goes all the way back to ancient times. And even musically, the songs certainly go back to Byzantine times if not farther back. But the custom is probably much older. I won’t share the name of the village to protect their privacy. But I did record some of the music making. And it forms the core of the second to last piece of the Musique con Crète album. The piece begins with some ambient sounds and then you can hear a lot of people singing—one person is singing, and the others are responding in a kind of call-and-response format. I can’t describe to you the shock I felt that this surely ancient ceremony continues today on Crete and is really just a part of everyday life in this village. I felt so fortunate to witness this certainly ancient cultural heritage. The music too certainly reached back to Byzantine times if not before. I was just so fortunate. I didn’t have to do much searching, or do any research really. This extraordinary cultural and musical experience just fell into my lap. I went to help a friend shear sheep and I found myself in the middle of antiquity.

***

Yona Stamatis teaches at the University of Illinois Springfield.

Other Links

Website: tasosstamou.com

Instagram: @tasosstamou

Facebook: Tasos Stamou