Marooned in the Greek American Archipelago

By Gerasimus Katsan

(Interview questions by Yiorgos Anagnostou)

Gerasimus Katsan is Associate Professor of Modern Greek and Chair of the Department of European Languages and Literatures at Queens College—City University of New York. He is the author of History and Ideology in Greek Postmodernist Fiction (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2013) and most recently he co-edited the volume Retelling the Past in Contemporary Greek Literature, Film and Popular Culture (Lexington Books, 2019).

Yiorgos Anagnostou is Professor of transnational Modern Greek studies at The Ohio State University.

I. Salt Lake City

YA: What was it like to grow up in the Greek American world of Salt Lake City in the 1970s? What aspects of the Greek American family and community do you remember the most, what was it if anything that left an imprint on you?

GK: I have a lot of wonderful memories associated with growing up as a Greek American in Salt Lake City. We had quite a large extended family that included both blood relatives (mostly second and third cousins) and an ever-growing horde of koumbari (godparents and in-laws). In the 1920s my father’s aunt had emigrated from Tripoli in the Peloponnesus to marry a miner in Bingham canyon, where she already had relatives who had gone to Utah the decade before. This is how we ended up in Salt Lake in the first place. My parents both grew up in Piraeus, and my father was in the Merchant Marines in the mid-1960s. On one trip the company he worked for left him stranded in New Orleans. Waiting for his next ship and with nothing much better to do, he took the opportunity to visit his long-lost aunt in Salt Lake.

As my father told the story, he immediately fell in love with the place, and, partially with the encouragement of his relatives there, he decided to give up the sea and move to the high desert. When he got back to Piraeus he simply told my mother, “pack everything up we’re going to America!” You can imagine her shock! His aunt’s first cousin, whose parents had emigrated in the 1910s, and who had become a successful and wealthy restauranteur, sponsored my father. The relatives in Utah, perhaps remembering their own experiences in the early immigrant days—and who had all had their names shortened—convinced him to shorten his name from Katsaounis to Katsan. Dad said if he was going to change his name it should become an “American” name like Brown, but they talked him out of it. Shortly after the family arrived (my twin brother and I were born six months after the family emigrated) my father found a very good job at Union Pacific railroad, which used the same type of diesel engines he had worked on in the ships. My father relished telling the story of what happened when his initial work visa expired, and it has become part of our family lore. He had to go to court to explain why he was “illegally” working for the railroad and not in his uncle’s restaurant. When the judge declared he was illegal and should be deported, apparently my father pointed at me and my brother (he had brought us to the hearing) and told him, “Send me back if you want, but you’d better take care of those American babies yourself!” The judge decided to let us stay.

My father likely adjusted to life in America relatively easily, especially since he had an amazing talent for languages and already spoke Spanish fluently and English fairly well. But my mother had a much more difficult time. After a few months she decided she did not like living in the States and took all four of us children back with her to Piraeus. For a year afterwards, my father wrote her charming love-letters and he eventually sweet-talked her into coming back to Salt Lake. In the first years she stayed at home to take care of us. She slowly learned English, and spent most of her time with the relatives and other young mothers in the community. She decided to get a job when we were old enough to start kindergarten. This was also difficult for my mother; in Greece she had had a good white-collar job working in a government office, but she found work as a cook in a junior high school cafeteria in Salt Lake. Her decision to work there also had to do with the fact that the school was close to home and the job coincided with school hours, so she could be home by the time we finished school. She worked there for twenty years. In the meantime, she also became very connected and involved with the community: she joined the church choir, the Philoptochos Society, the Daughters of Penelope; she taught Sunday school and also taught Greek in our Greek School.

One informal “institution” that my parents participated in was called “The Sewing Club,” which met once a month. This “club” had had its roots in the older generation where Greek women in the community would get together to sew, and visit, and probably gossip too! It may have begun during the Second World War when women would gather to sew or knit items for the soldiers, and it must have been something akin to a “quilting bee.” Originally this was a gender specific (female) activity, that adhered to the very traditional division of gender roles in the community. At some point, though, the women of the “Sewing Club” decided to bring their husbands along for parea and it simply became an excuse for large assemblages of family and friends (dinner parties, really), which were hosted on a rotating basis at the various members’ homes. However, they always referred to the gatherings as “The Sewing Club” long after there was no sewing involved. The traditional gender division continued, however: I remember the men would always gather in one room and the women in another. I would say, then, that my earliest memories and sense of being Greek are tied up with the family, family gatherings, and spending time with my cousins. My mother and aunts were superb cooks, so naturally a lot of my early associations have to do with food.

By the time I was born, of course, the old Greek-Town of Salt Lake which had been situated in the neighborhood around the still-existing downtown church and what is now Pioneer Park, had long since disappeared. The majority of the community was scattered around suburban Salt Lake Valley, mostly on the East Side. The old downtown church (Holy Trinity) was still the center of Greek American life, but I attended the newer sister church of Prophet Elias in the suburbs. While there were two churches, the community was a single unified parish, which was a strange arrangement but one that was extremely important to us. In those days we did not want to have separate or competing communities. Holy Trinity tended to be more traditional and catered to the older immigrant community; church services, for the most part, were entirely in Greek. Prophet Elias seemed to have a younger demographic, and more children, and more mixed-language services tending towards English. When I grew older, and especially after I joined the church choir, I came to prefer hearing (and singing) the services in Greek. There was something about the rhythms, melodies and the language that seemed intrinsically connected and beautiful, and which got lost in translation.

As in most Greek American communities, our two church buildings themselves and their grounds became the sites of the Greek experience. For us the churches offered something deeply meaningful: they were little islands of Greekness in that sea of Mormonism that surrounded us, where our ethnic identity and our participation in Greek culture largely happened. There we got to see our Greek friends, who were our “real” friends not just neighborhood chums or school acquaintances. Naturally attending church on Sundays was important, and the development of a religious identity was essential given that we were confronted on a daily basis with the hegemony of Mormon religious and cultural practices. In Utah, difference was almost exclusively expressed in terms of religion. For example, one of the first things someone would ask you when you first met them was: “Are you Mormon?” If the answer was “No,” often if the interlocutor was a Mormon the conversation would end abruptly. They wouldn’t waste their time on a “gentile,” which is what they called non-Mormons. In fairness, I should say that sometimes it was the non-Mormons who reacted negatively towards Mormons. For the Greeks, having a strong sense of affiliation with the Orthodox Church became one of the ways that we could be proud of our difference and our distinctiveness.

Beyond the religious aspects, however, the churches provided the space for many different types of secular activities, from Boy Scouts to folk-dance groups to athletics. A typical week might include three or four nights of activities held at the church. Our Greek Orthodox Youth Association (GOYA) teams usually competed in leagues organized by the YMCA or the CYO, where we met and played against all the other non-Mormon denominations. The community organized lots of events, both religious and secular, such as glentia and horoespirides (parties and dances) that would give us a chance to socialize, listen and dance to Greek music, and, of course, eat Greek food. We were lucky that Salt Lake was big enough to support at least two local Greek bands, and so live-music was typical at such events. The annual Greek Festival started as a small fundraiser, a “bazaar” organized by the women of the Philoptochos Society around 1970. The little pazari grew and grew until it became a major cultural event in Salt Lake, a celebration of Greek identity, and a way to share with the wider community something of Greek culture, food, and religion. The festival created a feeling of pride in the community within our own cultural space, but it also allowed us to invite non-Greeks to participate and experience the Greek community as well. This sense of pride was important, as I’ll explain later. It was always a great party, and a way the community could share the hard work as well as the fun of putting on such an event. This was usually a unifying event for us, and important to participate and volunteer. Weddings were another big deal, and we always looked forward to the splendid (and usually extremely fancy) wedding receptions. I think there was a lot of competition within the community there: who could throw the most extravagant wedding party?

Another secular space for us was Greek School. While there were Greek schools at both churches, we had a separate Greek school in West Jordan two afternoons a week that gathered the kids of families in the southern end of Salt Lake Valley who lived further away from either church. The school itself was a small house owned by a Greek family (I think it also operated as a day care center, but my memory is foggy) and across the street from a small Greek-owned supermarket. Although we were never overly fond of studying grammar (what children are?), I always looked forward to it just to be with my Greek friends there. My mother began her career as a Greek School teacher there, and she continued to teach in the Prophet Elias school long after the West Jordan school closed.

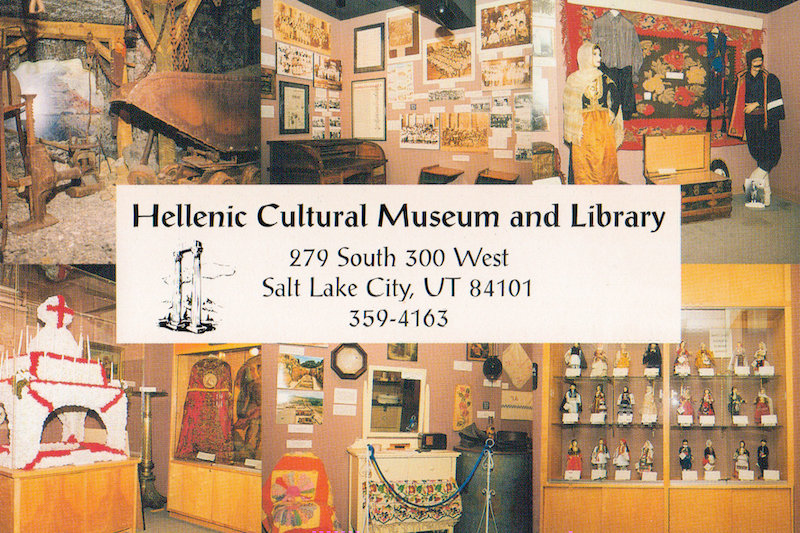

In the early 1990s the community decided to create a Hellenic Cultural Museum that recorded and told the story of the community. A lot of the immigrant generation, and even their children, were miners, and the museum focused a great deal on the mining communities. Several of my own relatives had worked in the Bingham Canyon open-pit copper mine, and they were always extremely proud of their association with it. I think for a lot of young Greek men in the community the mine was often their first job out of high school, and it was kind of a rite of passage to have worked there. I vividly recall how my relatives liked to talk about the mine and their experiences in it, as well as the town of Bingham where many of the mine-workers lived or had grown up. Bingham has long since disappeared; it got swallowed up by the mine itself as it got bigger and bigger.

One of my favorite experiences when I was a teenager in the 1980s was as a member of the Salt Lake Men’s Chorus, which was organized by Paul Maritsas, our choir director at Prophet Elias. He had written arrangements of many of his favorite songs in four-part harmony, and he wanted to try them out for male voices. The group really began when he invited some of his friends, the older men in the choir, to try out the arrangements. My dad joined, and recruited my brother and me as they needed tenors. Not only did we learn and sing traditional and popular Greek songs, but we traveled around to all the Greek communities in the area and performed for them. It was usually a big event in those small towns, even though it must have been a pretty corny show we put on (a cappella arrangements of songs like Kokkino Garyfallo). We went to a lot of communities in places like Price, Utah, Pocatello, Idaho, Ely, Nevada, Cheyenne, Wyoming and even Denver, Colorado. There was a lot of camaraderie on the road, as well as a sense of offering something, especially to the smaller communities that might not have the chance to have many Greek cultural events. For me, at least, it also gave me a sense of belonging to a wider Greek community in the Intermountain West.

YA: How about the American life as you experienced it in the city and the region at the time? Were there any conflicts between the two worlds, the world of family and the ethnic community, and the world beyond? What compelled you the most about American culture?

GK: I grew up in a suburb called Sandy, in a subdivision called White City. (The irony of the name was never lost on us—we never felt quite “white” there.) Although demographically things have changed considerably in Utah since those days, in the 1970s Salt Lake was probably 90% Mormon, and it still is the capital of Mormonism throughout the world. Most Mormons were of Northern European ancestry, and we Greeks were definitely seen as “others.” The Mormons tended to exclude the non-Mormons from many aspects of what was then the mainstream culture. (Some would argue that “Mormon culture” was not exactly mainstream “American culture” either, but that is a different discussion.) I suspect practically all non-Mormons in Salt Lake came to feel in some sense that they were part of an “unwanted minority”—and I know I felt that way a lot of the time. Some of my most painful memories as a child have to do with being excluded or bullied by Mormon children, and sometimes even by their parents. Nevertheless, my brothers and I did play with the Mormon kids our age in the neighborhood, most of whom were good pals and didn’t make any fuss about us being “gentiles.” But we tended to gravitate towards anyone who was non-Mormon. Naturally there was a constant discourse of us vs. them which fostered a bit of animosity and also led to a great deal of solidarity amongst non-Mormons. None of our Mormon friends really became close—our closest friends either were in the Greek community or were other non-Mormons. My oldest, most significant childhood friends—and the ones who are still my friends today—were Greek.

I can say honestly that there wasn’t much that compelled me about Mormon culture, which always seemed pretty bland. The Mormons themselves, although from German, British and Scandinavian stock, never seemed to express any sort of ethnic identity at all. I’m sure they thought of themselves as plain-old good Americans (whatever that might have meant), but their main interest was in their religion and their religious identity. For example, while the Fourth of July was celebrated, the really big summer holiday was July 24th, which commemorates the arrival of the Mormon Pioneers in 1847, after they had left the United States to try to carve out their own empire in the wild West. The Mormons also seemed fairly insular and unaware of other cultures or religions, even other Christian denominations. I remember being asked if I still believed in Zeus when we studied Greek mythology at school. Perhaps this is why the Festival became such a big event in Salt Lake, since it presented a sense of the richness and vibrancy of Greek culture (even if to us it seemed stylized, idealized and even a bit cliché) that stood in such contradistinction to the extremely “Wonder Bread” quality of Mormon culture.

In general, though, I would say that we participated pretty fully in American culture too: we played sports, we watched TV, we listened to popular music, we went to the movies and to high school dances, and watched the fireworks on the Fourth of July: the usual stuff. For years I played bass guitar in a garage band with my brother and numerous Greek friends, but we never dabbled in Greek music at all: we loved rock n’ roll.

YA: You have mentioned informally to me the power that Salt Lake City (and Utah in general?) exercises on your person. Is SLC a home? Help us understand this connection.

GK: I have jokingly been called a “regionalist” because of my almost nationalistic expressions of love for and attachment to Salt Lake and Utah. Salt Lake was like my horio (village), like my patrida (homeland). In a way, it seemed a part of my identity, who I am. I realize there is an awful lot of nostalgia wrapped up in this. Of course, I had grown up there, all my closest friends and relatives were there. It is home. When I left Salt Lake I felt like one of those villagers from Greece who took a handful of dirt in an amulet with them so they would have something of the homeland to hold onto. For me it was my Utah Jazz sweatshirt. I grew up in the mountains, and Utah is a very beautiful, mountainous landscape. Later, when I began to study nationalism, I came to realize that the constructions of nationalist ideology, which are often strongly tied to the expression of deep, “naturalized” feelings for or connections to specific geographic locations or landscapes, could be easily transposed onto a similar kind of construction of a “local” identity. This resembled the attachment I had to Utah as a place. When I started to read Greek literature, I came to have a deep affinity for narratives of immigration and the immigrant experience, such as in Hatzis’ Diplo Vivlio (The Double Book). To some extent I felt I could really understand the Gastarbeiter (guest worker) narratives of alienation and loneliness because I also felt like an immigrant, even though I had only moved to Ohio. (After all, it is a longer distance from Salt Lake to Columbus than it is from Athens to Berlin.) I had left my whole life behind me.

The strange thing is that I had a lot of ambivalence and suffered a lot of alienation when I lived there. The Greek community had begun to feel small and suffocating, the Mormons unbearable (we called it “living behind the Zion Curtain”). On some level I couldn’t wait to get away, to experience the wider world, to move on. It wasn’t until I left that I came to appreciate it, I suppose. Perhaps I simply idealized it and became nostalgic the way that immigrants do, remembering with great fondness what I loved and forgetting what I hated about the place.

YA: It was not the norm in the 1980s and 90s that a Greek American individual would major in English literature, let alone pursue a PhD. in the Humanities. Yet you pursued both. What was it that pulled you toward literature?

GK: I developed a love of books and reading early in my life. My father was an avid reader himself, and he had a very good collection of books at home, in Greek, English and Spanish, encompassing a wide range of topics from history, philosophy, literature, poetry, popular fiction and the sciences. He encouraged (my older brother would say “forced”) all of his children to read. When I was still quite young he caught me with his copy of Jaws by Peter Benchley, which he promptly took away as “inappropriate.” He made me read The Greatest Story Ever Told by Fulton Oursler instead, which naturally I found dull and moralistic by comparison, and which I never finished. He bought us a giant set of encyclopedias which I loved to read, fascinated by the variety of topics and the way it seemed to contain the vastness of the world. I was also extremely fortunate that we had a small branch of the Sandy City library literally just around the corner in a building the size of a residential house. It was one of the places we were allowed to go to alone, and I would spend hours and hours there. At one point in my college career I considered library science as a major, and worked in the Salt Lake public library for several years. I suppose the pull towards literature came from this exposure to a lot of great books. Along the line I fancied myself a poet, and even published a poem or two here and there. For a year I worked as an assistant editor at a local arts magazine. I also had a couple of great English teachers who inspired and encouraged me.

YA: How did your immediate social environment respond to your academic interests?

GK: I take this to mean how did the Greek American community respond to the fact that I wasn’t studying to become an engineer, a lawyer, a dentist or a surgeon! My parents were simply happy that I was going to college and supported me without worrying too much. I don’t think I ever got any “flack” from anyone for pursuing English Literature. My father’s cousin was an elementary school principal whose wife was also a teacher. On the whole “English teacher” was a respectable choice, which I imagine is what they thought I would end up doing at the time. Moreover, we had a couple of prominent historians in the community, one of which was the acclaimed Greek Americanist Helen Papanikolas, so a Humanities degree wasn’t something people thought negatively about. In any case, I was going to college and earning a degree, which was the acceptable and expected thing to do.

II. Columbus

YA: Help us understand, what did it mean to you, on a personal level, to study modern Greek culture in an academic setting?

GK: It meant everything to me. I had made the cataclysmic decision to leave home and to pursue graduate studies at Ohio State. It was one of the most important decisions I ever made and was a turning point in my life. Graduate school provided me a new set of spaces where I could make meaningful connections to aspects of Greek identity and culture that I had not known before. In a way I left my Greek American roots behind as I began to focus more specifically on Greece. I underwent a sort of reorientation of belonging that led me towards contemporary Greek culture, and one that took place in the secular space of the university. At the same time, I did not really connect with the Greek American community in Columbus; as a “newcomer” I could not find the same warmth and sense of belonging that I had felt in Salt Lake.

At the beginning it was extremely daunting. I felt very isolated and completely alone for the first time in my life. I was also a twin, so being separated from my twin brother deepened my loneliness to what I can only describe as despair. Then again, graduate school is so difficult and the workload so overwhelming that probably I didn’t have too much time to be depressed. Luckily, I made one very good friend early on who helped me through it. I was also lucky to get to work with some incredible scholars who were leaders in the field; I am very grateful for the dedication of my professors at Ohio State. What was great about studying there was that we had the resources of a large research institution but were in a small program where I got a lot of care and individual attention.

When I got to Columbus, I discovered that my Greek was not up to snuff, especially compared to fellow graduate students who were native speakers. While I had had lots of Greek School as a child, over the years my use and knowledge of the language had deteriorated. As an undergraduate I studied Modern Greek at the University of Utah, and although the instructor was a well-meaning and beloved member of the community, he was not a particularly good teacher. Thus, I always felt I was toiling under the handicap of being ill-prepared in Greek, and not knowing enough about the modern culture. I worked really hard to re-learn and improve my Greek so that I could function on the level required by my studies. Even today I would never claim that I have “native” ability in the language, and it is a constant source of feelings of insecurity for me; once in a while I am still taken by surprise when I get compliments from colleagues on “how good my Greek is for an American,” which, of course, is a back-handed compliment and causes me a lot of complicated emotions.

For the first time, too, I came into contact with many students from Greece. I got a lot of hazing for being an amerikanaki, which is really a pejorative term for a Greek American “bumpkin” who has learned the traditionalist, old-fashioned version of Greek village culture but has limited knowledge of contemporary Greece and doesn’t know anything much about the current culture. To a large degree wanting to belong amongst those students, as well as my colleagues in the Modern Greek program, made me work hard to “prove” I was “Greek enough.” Paradoxically, it felt extremely unjust and frustrating to be looked down upon by Greeks from Greece as someone not really Greek and without “legitimate” claim to the national or ethnic identity. Their nationalism—which involved a monolithic and often one-dimensional understanding of Greek identity that emanated solely from the nation-state of Greece—sometimes got in the way of real communication, friendship and understanding. There were not many Greek Americans amongst the students I knew, so I often felt the odd-man-out. This was particularly the case in terms of cultural literacy; I had not shared the experiences that my fellow students had had growing up in Greece, and so I simply could not understand or relate to a lot of things that were important to them.

YA: Why did you opt to pursue modern Greek instead of Classics, Byzantine or Greek American studies?

GK: This is really complicated, and I think there were many contributing factors. In part it was my own “discovery” of Greece. We had a large family and so it was difficult and expensive for us to visit Greece all together. I had only been to Greece once as a child, spending the entire summer there when I was 7 years old. That trip was magical, and remains somewhat mythologized in my memory. Later I realized that on that trip we had visited Greece soon after the Junta had fallen, which, aside from just my own childhood wonder at all the new experiences, is probably why I remember there being an incredible atmosphere of joyousness and freedom. In my childish way it seemed to me that living in Greece was just one big party full of fun, music and long, glorious days at the beach. I didn’t have another opportunity to visit Greece until I was 21 and an undergraduate at Utah. Visiting Greece for the first time as an adult and without parental supervision was an important event. I think those two trips planted the seeds of wanting to explore Greece and Greek culture more fully, beyond what I had known as a Greek American—which often had seemed filtered, watered-down or “pre-packaged” by the community when I was younger.

For example, I had always felt a little irritated by the preponderance of references to Ancient Greece in our experiences of Greekness in the community, as well as just in a general way in Western/American culture. We were forever being told about the greatness of the ancients and how we had to live up to these impossible ideals while also being slightly embarrassed by modern Greek culture as being a bit rustic, old fashioned, backwards and unsophisticated. (I remember as kids we used to make fun of the most recent immigrants as “OTBs”—just “off the boat”—even though it hadn’t been that long ago since our parents had come to America.)

In a way we embodied the Hellenic/Romeic schizophrenia that so many scholars have analyzed. It was always somewhat confusing that we celebrated our folk culture roots at events like the Greek Festival and through so much communal folk-dancing, through celebrations of national ethnic holidays and religious observances, but that we also were given to understand that it was somehow “not as good” as ancient Greek culture. For me, then, studying modern Greece and Modern Greek literature was a way to get away from the folkloricized versions of Modern Greek identity I had experienced, and to see the modern country and its culture, literature and history, as valuable and important.

Moreover, I always resented the fact that in school I was inevitably expected to know all about whatever ancient Greek subject we happened to be studying, whether it was mythology, architecture, or some other aspect of ancient Greece. Somehow as a Greek I was supposed to already know about these things and explain them to my fellow students. Even worse, there was never any mention of modern Greece as a country or a distinctive modern culture at school, except perhaps when we studied European geography. At the university even, for example, whenever some obscure classical reference came up in a difficult modernist poem, my professors somehow expected that I would be the one to unpack and interpret it for the class. This became extremely tiresome.

That I also steered away from Byzantine history, culture, and literature probably also has to do with the way the Orthodox Church was so indelibly a part of growing up in the Greek American community and a part of Greek American identity. Now that I think of it, though, this is strange to me, because as an undergraduate I studied a lot of medieval literature, and loved Chaucer in particular. Perhaps I felt Byzantium was somehow something I already knew a great deal about through the Church, and of course it was something I associated as much with theology as with history or culture broadly speaking. I remember my father had the two-volume edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; I had pored over the chapters on Byzantium with much fascination, and was disappointed at Gibbon’s negative view of the later empire. His classicist snobbery insulted both my Greek and my Orthodox sensibilities. I had also read some Byzantine texts in translation, such as Procopius’ Secret History. In the end, however, Byzantium became more of a hobby than a real burning academic interest.

I don’t think it ever occurred to me to study Greek America itself as an academic topic. Possibly I felt it was problematic and “too close for comfort” as someone who grew up in the Greek American community. Also, as I mentioned above, by the time I came to graduate school I had begun exploring my own identity more broadly as a Greek vis-à-vis contemporary Greece.

The result was that I chose to study postmodernism and the most contemporary Greek literature possible.

III. New York City

YA: What is the place of modern Greek literature and more generally modern Greek learning in your life? If you were to choose a favorite Greek novel, what that would be?

GK: Modern Greek literature and learning are central to my life. As a professor of Modern Greek, I am constantly engaged with these, both through my teaching and my research. I have read so many great novels, and there really are many great Greek novelists, that it is impossible to say that I have a “favorite.” Some novels hold particular significance for me, especially novels of exile that seemed to resonate a lot with what I felt when I left home: Hatzis’ Diplo Vivlio and Kranaki’s Philhellenes, among others. Novels such as these helped me to understand my own experience of living between two cultures, and often of feeling alienated from both. Such narratives were also useful in seeing how easily one could be trapped in a very narrow vision of ethnic or national identity, which could limit how one perceives, interacts and understands the wider world and one’s place in it. Many of the novelists I like to read and study use history as a major theme or point of departure. Cavafy is another writer I love because of his special sense of diasporic Hellenism and his exploration of a wider Greek identity that goes beyond mere nationalism.

YA: What is your experience like with teaching modern Greek literature to Greek American students? Is there a particular work of modern Greek fiction that generates strong student interest?

GK: Teaching has both many joys and many frustrations, of course. I love sharing what I have learned about Greek literature with my students, and I am always happy when my students teach me new things about what we read that I never saw in them. Students relate to various texts in different ways; contemporary novels seem to give them something that resonates with their own experiences. For example, I have taught Sotiropoulou’s Zigzag Through the Bitter-Orange Trees, which, although the story itself is told from a rather critical perspective about the bleak, shallow pop-culture landscape of life in modern Athens, my students recognized a lot of their own experience and could relate to a story about young people negotiating their way through the difficulties of life. The characters’ desperation and angst in coping with modern society, with the pressure to succeed, with the pressures of family life and the heavy expectations placed upon them, opened many thoughtful and, I hope, meaningful discussions in class.

YA: What is the place of Greek American culture today in your life in New York City? Do you interface with any local/community institutions?

GK: This is also difficult to gauge. I operate within what can be seen as an important Greek American institution that serves a large number of members of the community: the Modern Greek Program at Queens College. This has given me a network of contacts to different types of institutions and points of contact with the community. When I have time outside of work and family I sometimes attend academic and cultural events, such as lectures, the Greek Film Festival, or the occasional Greek play. What is great about living in New York is easy access to all sorts of things, particularly restaurants, cafés and Greek supermarkets.

YA: Do you follow Greek American popular culture, and the way it represents Greek American history and culture? Is there something in particular (a film, a documentary, ethnic lore) that you love? Is there something about these representations that you feel strongly about? Something that it is not shown, and you would have liked to see.

GK: I can’t say that I follow much Greek American popular culture specifically, though I wouldn’t say I actively avoid it either. My focus, however, is most often on Greece and trying to keep up with things there, especially the contemporary literary scene, which is hard to do even in the days of the internet. This has a lot to do with my professional life, of course. Also, as I mentioned before, I reached a turning point when I began to study contemporary Greece and also began traveling regularly to Greece in the summers. My energies are no longer directed towards my Greek American identity as such, but more in making wider connections to contemporary Greek culture. Perhaps in middle age I have reached a place where I am simply comfortable with who I am and I don’t need to continually seek affirmation or representations of my identity through external sources.

YA: What is your favorite Greek American novel? What makes it important?

GK: Although I am fond of A Dream of Kings, I would have to say Petrakis’s In the Land of Morning. It is important since it captures the Greek American community in the very specific historical moment of the early 1970s, a moment of painful transition where Greeks were leaving their old urban ethnic neighborhoods and moving to the suburbs, and when traditional Greek American values were being tested, questioned and transformed by the larger events of American history. It shows the conflict between the immigrant generation and its disillusioned children, not just the “good” kids who went to college and became “successful,” but the “bad” kids who “failed” and slipped through the cracks. Its context of the wider theme of returning Vietnam War veterans also makes it more than merely a “Greek American novel.” For me this is the least “Kazantzakian” of Petrakis’s work, the least mythologizing or heroicizing, and where he is perhaps at his most critical of normative or idealized constructions of Greek America.

YA: What is your favorite Greek American book? What makes it important?

GK: Papazoglou’s Chronicle of Halstead Street. For me one reason Papazoglou is important is because she is a Greek American writer who insists on writing in Greek in 1962–even though that was really an unsustainable project in the face of the assimilation and the Americanization of Greek immigrant communities. Although her books are out of print and she is practically forgotten, her stories deserve to be translated into English. Of course, she represents the immigrant generation, and the experiences of immigration in general, which is why she could have wider appeal to readers of other ethnic/immigrant communities. Her story “Suspended Souls,” for example, captures the conundrum of the Greek American experience like no other, and I think it could probably resonate even with the experience of young Greek Americans today.

YA: Please raise your own question(s) and/or share with us what you think is important in this conversation.

GK: I think however tight-knit or all-encompassing a community might seem, individuals understand and participate in that community in their own unique way. Hearing about or recording those individual experiences can be an important way to come to know a given community more deeply. Greek America is more diverse than we might believe, even though the structures and institutions of Greek America have often sought to impose a kind of overarching or even monolithic version of itself and its perceived values. For me there has always been too much focus on the metropolitan centers such as New York and Chicago—although that focus is understandable given the large size of those communities. The Greeks went all over the United States, though. The smaller Greek communities have also been extremely vibrant, and can tell us a great deal not only about a different part of the Greek immigrant experience, as Helen Papanikolas showed in her work, but also about how Greeks and Greek culture thrive in places across North America, not just in two or three cities. The story of the Greeks in Utah adds another dimension to the broader story of Greeks in America precisely because there we had to negotiate our identity and our culture in the face of a very distinct and very powerful mainstream culture. If our experience mirrored what happened elsewhere in America, then it was also intensified by the very specific conditions produced by living amongst the Mormons. That said, can I say that my own experience is “representative” of the Greek American community of Salt Lake? After all, I am one of those who left home to explore a side of Greek culture that somehow I had not known fully while I lived there. I made my own voyage through the networks of the Greek community, one that was “long, full of adventure, full of knowledge.” I never moved back to Salt Lake, as did some of my friends who went away to college. Instead, my ship has come to dock on one of the larger islands of the Greek American archipelago.