From The Day After The Day After

By Andrew Mossin

The boats from Zagora have departed.

Eleni has departed also; she has gone to a foreign land.

She sent me no letter; she sent me no reply.

She only sent a kerchief, a black kerchief.

“Mother, I will go away. I will go away to a foreign land,

far away to a distant land, and I will never return.

Put on your black clothes! Put on you dirty clothes!

Whenever I set out for home, I meet rain and mist;

and whenever I turn back to that foreign land, I find sunshine and good roads.”

—Greek funeral lament, quoted in Loring M. Danforth,

The Death Rituals of Rural Greece

Some bare facts. I was born to Greek parents on April 20, 1958, both of whom had been born and raised in Liknon, a small village in the Thessaly region of Greece. My mother’s name: Angeliki Sakkas, age 23, at the time of my birth. My father’s: Efthimios Kooroubis, age 34. Shortly after giving birth to me in Athens, Angeliki gave me up for adoption—though not before I had been christened, Antonios. There’s uncertainty about what happened in the immediate months following my birth or why my mother chose to remain in Athens, rather than return to her home village. As to my father, I have no concrete information about what became of him. Apparently, he left his and my mother’s home village soon after she related to him that she was pregnant with his child. Did he ever return to seek information about Angeliki and the child to whom she gave birth? No one can say. I will likely never know.

When I was nearly a year and a half old, I was adopted by Iris Alford and Richard Mossin (my mother used her maiden name to the end of her life) and flown to the U.S. aboard an Olympic Airlines flight. We landed at Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International) on a Tuesday in October. According to my father’s account, told to me years later, there had been steady rain for several days, and when I was brought from the plane to Iris and Richard waiting on the tarmac below, the rain formed a light film on my face so that my father was convinced that I had come to them with fever. Iris apparently turned to my father and said, “He has your mouth and eyes.…” In my own reconstruction of events that day, I imagine my father would have turned away from her at that moment, both embarrassed and proud of his orphan son who had arrived in the early fall a little less than two year after he and my mother had first considered the idea of adoption.

*

Blood is distant…. Words can’t recover what was lost. A landscape back of those who carried me through my first days: that mother, that “she” who bore me. I only came to know my mother’s name, Angeliki Sakkas, in my mid-20’s when my father, preparing to leave on a trip to China in the coming week, presented me with my birth certificate and an index card on which Angeliki’s name and that of my father, Efthimios Kooroubis, were written. Initial knowledge of the circumstances of my birth parents came to me from Iris. I was perhaps five or six, had already come to realize that my place in our household was unsteady, foreign, when my mother told me the story of my birth—one story among several that shifted over the next several years, depending on my mother’s mood. In an early telling, my parents were peasants who lived in the countryside, not far from Athens. One day my father approached my mother in an olive grove near her home and took her into the field where he raped her. When she became pregnant, my father (who served in the military and lived in a nearby town) refused to help and abandoned her. My mother sought the assistance of the local court, but had no luck in forcing Efthimios to provide her assistance in the months prior to her giving birth. Having no other options, she traveled to Athens and gave birth to me in the children’s hospital, where several weeks later my mother left, never to set eyes on me again.

“You were a bastard child,” Iris, the mother I knew, would say at other times, emphasizing the word “bastard,” as if it were the break in a continuum that stretched back further than I could ever know or understand. “You were a bastard, unwanted by either of them, that’s why you were left in the hospital, and even there, no one really wanted a Greek baby so many months old already, no one.” I would alternately listen and turn away, try not to hear her at these times when the story’s violence shifted to the child that had been the product of that initial act of rape. “Your father was a peasant and your mother a peasant too, neither had any education. What can you expect? This was the act of ignorant people.”

It would often be late at night, long after my father had gone to bed, when these conversations would take place. Not that they were conversations, more like monologues, as my mother held in her hand her glass of scotch, sometimes gin, and recited to me the same shifting story, parts of it, again and again. And if I turned away, if I tried to walk out of the room, she would whisper after me, “bastard,” and the word was like a wound that wouldn’t stop opening, that kept bleeding from the same part of my flesh, and sometimes I’d hear the word in my dreams and see Angeliki advancing over a stony hill, in her arms a burlap sack filled with wood, and her eyes would be set on the hills ahead of her, and behind her, there would be men’s voices following, calling her names as she moved on without looking back, without offering them the chance to let her know she was listening.

*

What could I believe from what my mother told me? Nothing. Nothing at all. Everything. Sent to my room after these sessions of storytelling, I would envision the woman related to me on the ground, near a field dry and broken from the heat of summer, and would see her face as if turning toward me for help. And then there were all the other nights in our house that passed without incident, without my secret name coming forth, name from another lifetime that would never be inhabited by me. And just as suddenly his name and the figure he represented—Antonios—appeared again, late at night, in Iris’s voice cracked from tobacco and scotch, her eyes heavy and without feeling, as I stood before her again in the center of our living room and listened once more to these strange tales about a mother and father I would never know, my inception presented again and again as violent, traumatic, brutal, and something else—it could never be undone now that it had happened. What could I believe?

There was, I always thought, one who stood behind the one I was told of, and I would learn her name one day. I would learn her ways one day. There was one, I said, inside of me not a bastard, there was the not-bastard who hadn’t been born, as if a twin existed in the world, a twin who bore a different name and lived across the ocean from me, who kept house with a woman in her 50’s, lived on the first floor of an apartment house near the eastern part of the city, went with her each day to market, helped her as she rose up the stairs at night to return to her flat that was just above his.

Angeliki, the woman who had given birth to me and traveled from her village to Athens that spring to do so, she would come back to me years later through the poetry of Sappho, Constantine Cavafy, Angelos Sikelianos, Odysseus Elytis. I read to understand a world, yet the world repeatedly veered out of view, as if none of the poets I came across could be integrated into this heightened origin narrative that had been made one of my core stories. The image of Angeliki, helpless, dragged to the side of the road, then into the olive grove, remained with me, outlasting Iris’s words, outlasting my own efforts to recreate other versions in place of this primitive tale of sexual violence. It was as if I became Angeliki in my imaginings, followed her as she must have gone that day and when she fell on the stones of the road near the town center, I fell again with her. I stayed beyond in the fields and counted her cries. When she began to bleed from where he’d pulled at her clothes and scratched her with his fingers, I could smell and taste the blood flowing from her wounds. I wept as she did by the roadside and brought myself to my feet as she may have and wandered back down the road toward my native home, to be greeted by silence and later anger as she must have been treated in those days by her own family, unable to accept her pregnancy and forcing her leave her home and village and travel to Athens. There she would remain for the rest of her life, working first as a seamstress, then later as a custodian in an apartment building, always keeping a private history intact from those events that defined her adult life following my birth and adoption.

*

She draws near with her clouded eyes, that sculptured hand

the hand that held the tiller

the hand that held the pen

the hand that opened in the wind,

everything threatens her silence.

George Seferis

In 1994, then a graduate student in English at Temple University and living in a studio apartment in Center City Philadelphia, I began a correspondence with representatives of International Social Services (ISS) in New York, the organization that had helped arrange my adoption in 1959. What prompted this initial search? Partly the work I’d been doing in my own writing of poetry at the time—as I came to the same blockage time after time in the work. Having written a poem titled “Origins” early in my M.A. in Creative Writing (unpublished), I found myself afterward struggling to find ground, voice, narrative cohesion. Language seemed to be falling down around me each time I sat down to type, as if I were overcome by a kind of aphasia. The experience resembled my efforts to learn to read when I was five and six years old, my parents concerned that I might never learn to read proficiently, as the signs on the pages of the children’s book I was given floated before me, soundless, abstract, without reference to a world. In the midst of what was becoming a full-on recovery project for an identity, a subject, that was elusive, living elsewhere, perhaps nowhere, I turned my graduate student mind to genealogy, to my ancestry, as a way of grounding my being that had never felt more homeless, more astray.

In my first correspondence with ISS, I indicated that I was seeking any information their agency could provide me about the whereabouts, if still living, of Angeliki Sakkas. For reasons having everything to do with my complicated relationship to the violent Greek man narrated for me by Iris all those nights during my childhood, I didn’t even bother to inquire about the whereabouts of my biological father. I was later contacted by an agent from ISS and informed that my mother was indeed still alive and welcomed the news of my existence. In that same correspondence from the Athens branch of ISS, dated January 31, 1995, came a narrative of my mother’s life, including the following information.

Born in 1932 in a small village near Lamia, Angeliki had a brother who was 70 years old at the time and lived in Poland and a sister, 58 years old, who continued to live in the village where my mother grew up. Their own mother died when they were very young, with the result that Angeliki, the oldest of the three children, took on most of the responsibilities of the household. She wasn’t able to continue at school, completing only the fifth grade of elementary school, and soon after her mother died she went to work in the fields with her father. Some years later, she met the young man who would become my father and with whom she would become romantically involved. When Angeliki became pregnant, Efthimios refused to marry her and left the village. Because of the public scorn Angeliki would have faced in her village at that time as an unwed mother, she felt she had no choice but to leave Liknon and travel to Athens, where she gave birth to me at the Mitera Center for the Protection of the Child of Attica (established in 1955), where she stayed through her pregnancy and for three months after. She then started working as live-in domestic help, and in 1965 married through matchmaking. They remained together only five years and in 1970 were divorced. From 1965 on, Angeliki worked as a doorkeeper in an apartment building. For the next thirty years she lived in the basement of this block of apartments and, at the time of this caseworker’s writing to me, was seeking a better apartment in the same building.

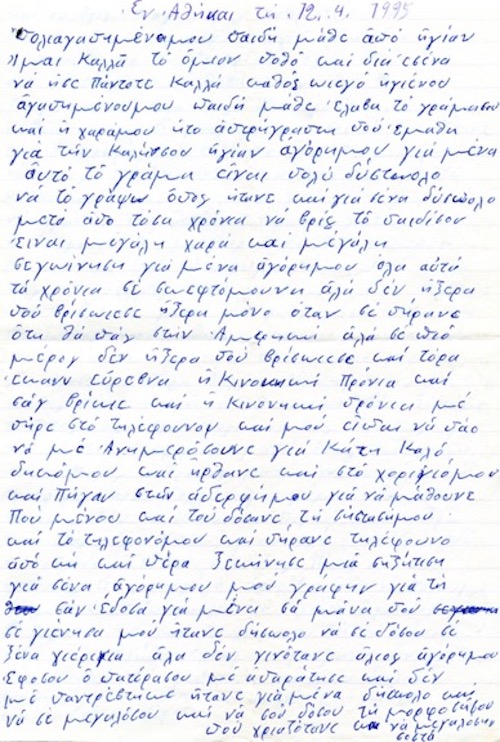

My mother’s first hand-written letter in demotic Greek followed later that year. Translated by the caseworker in Athens who had written the original communication, it arrived in late December:

Athens, 12.4.1995

My beloved child, I am in good health and I wish the same to you, to be always well.

My dear child, when I received your letter, I felt an indescribable happiness, mostly because I learned that you are well.

This letter is difficult for me to write, as it was for you.

I felt a great happiness and excitement that after so many years, I was able to find you. My boy, all these years I was thinking of you but I didn’t know your whereabouts. The only thing I knew, when they took you, was that you would go to USA, but I didn’t know the area.

Some time ago, the Social Service phoned me and told to go to their office in order to inform me about a personal matter. First, they went to the village where I come from, and communicated with my sister in order to learn where I live. Then my sister gave them my address and phone number and after they contacted me, we started a discussion for you, my son.

For me, the mother that gave birth to you, it was really difficult to give you to other hands, but unfortunately, there was no other way, my son. Since your father abandoned me and didn’t marry me, it was really difficult for me to raise you and to offer you the necessary education, in order for you to become a good man in society. I was poor and I could not offer you all that your adoptive parents offered you. I would really like to thank them because they were good persons, they raised you in the right way and gave you the necessary education in order for you to become a good man. And now, we are all proud of you.

My son, you should love your adoptive father, because he, as well as your adoptive mother, raised you from a very young age and they heard your crying and worries. Your adoptive parents themselves would have a lot of worries, because a child does not grow up without worries.

You wrote to me that your adoptive mother has died. I am sure that she offered you a lot and you should go and light a candle for her, who was such a good person.

Although I take a pension, my son, I continue to work, because pensions in Greece are very low and the cost of living is high. Here in Greece, we have great unemployment and young persons cannot find work easily. Others also, who have work are not able to face every day expenses.

My dear child, you wrote to me you had come to Greece in 1990, and were looking for me. But at that time, there were no telephones in my village, that is why you could not find me.

You wrote to me my son, that you are in love with a girl. If she is good, marry her, do not cheat and leave her. After you finish your studies, marry her and come with her to Greece. I will be very happy to see you, my child. And after so many years, I will see you as a young man, that you are now. When you come to Greece, we’ll say more.

I wish you my son to find the job you want, after you finish your studies. I wish with all my heart that God will help you to find everything you want in your life.

My son, Andreas, you have your birthday in April 20th, and I wish you to live like “the high mountains” and God to give you all the best.

Now, my son, I kiss you with great happiness and excitement. I, your mother Angeliki, send you many kisses and all my love. My son, Andreas, whenever you are able, I will be waiting for you to hold you in my arms. I would wish myself to be a bird, in order to fly and come to you my son and see you, and then come back again.

My son, I send you many kisses and the wish to see you soon.

My letter in response to this first letter from Angeliki, along with all the other letters I wrote to her, has not survived. This first letter from her would have arrived in the midst of my having met the woman who would in the next few years become my wife and the mother of my daughters, Mia and Isabel, born in 1998 and 2000 respectively. It’s impossible for me to recall my exact reaction to this first letter, though the disconnect between the accompanying translation of my mother’s Greek into halting English and the unreadable (by me) Greek in my mother’s hand must have seemed incoherent, irreconcilable. Sitting with the letter that winter in the apartment Madeline and I had begun to share in late 1994, I must have recognized the enormity of this discovery. And at the same time, it would seem I also had little way of connecting my daily life to that discovery, to the voice that rose from the pages of a translated letter from a woman from whom I’d been parted for almost 40 years.

A few months later, another letter from my mother arrived in response to mine, again with a translation by a caseworker from ISS Athens. This one would be undated, typed on plain bond, folded into fours:

My beloved and unforgettable child Andrew,

I am fine, as far as my health is concerned, and I wish the same for you.

Be always well my son Andrew, and I’m fine too.

I received your letter and my happiness was indescribable. I wish you to be always well like the “high mountains.”

I’m still working. What can I do my son? Life is very expensive. How can we manage? We should work until 100 years of age. Here in Greece, there is great unemployment and if someone has a big family, then at least 4 persons should work in order to be able face everyday expenses. The rents are very high. A two-room apartment costs 60,000 drachmas per month and if you add electricity, water, etc., then you need over 100,000 drachmas per month. If you count also the expenses for food, you can understand why I’m still working. I’ll work until I will be able, then I’ll stop. I already feel tired as I’ve worked since I was 8 years old.

In our village, we didn’t have much land and therefore my family couldn’t manage.

I was working like a man in order to help my family. My mother died when she was 40 years old. At that time my sister was 4 years old and I was responsible for her, also.

My father died when he was 65 years old.

My brother went with the guerillas at the mountains in order to fight Germans who invaded our country. Then the civil war was started and the one “brother” killed the other. The one “brother” was with the guerillas and the other was at the army and they killed each other.

The civil war ended in 1948 and at that time others got away in Poland, others in Soviet Union, others in Czechoslovakia and others in Hungary. Many Greeks had been dispersed in all East countries, as that time was very difficult for the communists.

There was much hate among people and due to fascism many people were killed, especially the guerillas who were fighting for freedom and independence.

The guerillas were imprisoned and exiled. Many of them were taken during the night and executed. Do you understand now, my child, why your uncle is living in Poland? He was forced to leave his wife and child and go to another country. In Poland, he married for the second time and made a new family.

The circumstances were such that my brother couldn’t return to Greece and therefore, I was the one who faced all the difficulties, my child. I have passed so many difficulties in my life, that if I were a writer I would write a book. I had enough of work, both to my village and Athens. I worked as a cleaning woman in houses, where my employers didn’t let me go out, not even to the movies.

My dear child, Andreas, it is very hot, here. But what can we do? It’s summer and we’ll suffer, somehow.

Well, my dear child, I do not have anything else to write you. I kiss you with many kisses.

Andreas, my child, I’m looking forward to receive your letter, the soonest possible.

I kiss you again with many kisses and I’m waiting for you and your wife, during autumn.

I send many kisses to your wife and your dear father and I wish you from my heart to finish your studies at the university, soon.

I wish you farewell till we meet in Greece.

I kiss you all,

Your mother

I let the silence go for weeks, then months. Resistance to opening a dialogue with this woman who had given birth to me persisted. I tended to my life as a struggling graduate student, to my new marriage, to the promise of some sort of new life. A year passed. My mother’s letters and cards arrived as if we had followed the course of our lives together, as if I could impart some language that would redress her wound that had opened again. “Let the speech that knows no lie,” the poet Odysseus Elytis has written, “recite my mind out loud.” I wanted to recite out loud the letters from my Greek mother, to put them next to those that remained from Iris, to ask of one, then the other, How can this be, how did this happen? that one claimed me, but didn’t want me; the other wanted but couldn’t keep me. Birth mother and adoptive mother, fused, not fused, echoing each other in their son’s life, so that what I could ask, what I couldn’t ask of either, of each of them, lay inside the words they spoke and wrote me. And the violence of one was tended by the gentleness of the other, and if I looked back to one I must have looked ahead to the other, awaiting me, as if she were the one I had sought all my life, without reason or understanding except that which blood gave me.

The last letter I received from Angeliki is dated May 31, 2004:

My dearest son Andreas,

I’m fine and wish the same also for you, to be always well.

Andreas, please forgive me that I didn’t write to you earlier.

What can I say, my boy? I’m running to the doctors and make medical examinations because I have to make an operation to my leg. If I leave it, in the course of time, I will not be able to walk. So, I must have this operation although I don’t have the money needed.

Only the doctor asks for one million drachmas for each leg. Besides the medical expenses for the hospital. I only receive a very small pension and I have difficulties even to cope with my every day life. As soon as I pay for the bills of electricity, telephone, shared maintenance expenses for my apartment, my pension is over and then again the same.

My Andreas, I would like to inform you that my brother is coming to Greece for good, after 60 years. As he has nowhere to stay, he will stay with me. He will bring with him also his grandson in order to find somewhere to work. He has studied something and knows also German and English. He wants to find a work at a hotel in order to earn some money before returning again to Poland, because life is difficult there.

Well, my Andreas, I told you my news. Write to me about your life, your children and your work at the university.

I kiss you and the children with many kisses.

I’m waiting for your letter.

Your mother

I don’t remember what I’d written back to my mother at the time. By that point, my marriage had ended in divorce, I was living in Carlisle, PA, teaching at Shippensburg University, and I saw my daughters every other weekend as part of an informal custody arrangement my ex-wife had agreed to. I recall contacting ISS to ask if I could send my mother the medicine she needed or money to buy such, and after a few weeks got the response that my mother didn’t want such help from me but was grateful for my having asked.

*

When my mother’s letters stopped arriving in 2005, I wrote to ISS again, requesting information about my mother’s condition. As I’d learned from the caseworker in Athens and as my mother herself had made clear in her letters to me, Angeliki hadn’t been well, suffering from phlebitis and other ailments. In December 2006, I learned from the caseworker that Angeliki had died sometime the previous year in Athens. No other details were provided to me and the caseworker indicated that Angeliki’s immediate family in Greece had requested that I have no further contact with their family. Surprisingly, this included Agatha, the daughter of my mother’s sister, who maintained a close relationship with Angeliki until the end of my mother’s life. I have pictures my mother sent me of Agatha, of them together, of my mother dancing at what must be a holiday celebration, surrounded by family.

Now the father of two children of my own, I was, for the first time in my life, without parents.

*

In the artifice of provisional memory, Angeliki is standing before me again on the black surface of a road in the bright noon day sun. Her body is clothed in black and she is wearing a gold necklace with a crucifix. In her hand is a book of poems she has brought out to read to me. The pages are marked with signs, leafy drawings she made when she was a child. I walk in the middle of the road, no traffic, a hot day, one of the hottest in years they had reported in the local paper. In the distance the fields, yellow, darkening, and beyond them a row of mountains I can imagine as they must have appeared to my mother when I was a child. “Angeliki,” I say. She doesn’t, at first, acknowledge me. Then a smile, slow, deliberate, and her eyes open wide in greeting. “My young son from the mountains,” she says to me, “you have come to find me. You have come back to your old mother and found her.” The sun is close to the treetops and level with my eyes as I take her in, as she takes my body into hers. There is lightness in her touch and the scent of olive wood and jasmine.

“Angeliki,” I say, “Your son from the mountains has come home to find you.”

In a small cemetery outside Liknon, a flat stone marks the site of my mother’s grave and bears the inscription: Αγγελική Σακκά 1932-2005. I am told that in the spring the fields nearby are awash in color from the poppies and wild roses that return each year and the olive groves fill the air with the lush fragrance of ash and cinnamon.

Note: This is an excerpt from a book-length memoir, portions of which have been published in Conjunctions and /nor.

Andrew Mossin is a writer of Greek descent whose work directly relates to issues of cross-culturalism, ancestry and national identity that arise from conditions of the Greek diaspora. His poetry, creative non-fiction, and critical essays have appeared in numerous journals and magazines, including Conjunctions, Talisman, Jacket, /nor, Golden Handcuffs Review, Callaloo, Contemporary Literature and many others. He is the author of five books of poetry, including Exile’s Recital (Spuyten Duyvil 2016) and Stanzas for the Preparation of Perception (Sputyen Duyvil 2019), and a book of critical essays, Male Subjectivity and Poetic Form in “New American” Poetry (Palgrave). He is an Associate Professor at Temple University, where he teaches in the Intellectual Heritage Program.

Sources

Elytis, Odysseus. 2004. The Collected Poems. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Loring, M. Danforth. 1982. The Death Rituals of Rural Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Seferis, George. 1995. Collected Poems. Revised Edition. Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Editor's note: For work in Ergon on the topic of U.S. adoptions of Greek children see here