Romancing Greek History: Sophocles Papas and the Cosmopolitan Classicization of American Music

by Nicholas Ezra Field

Abstract: Following the First World War, shifting demographics within American society stimulated an exhilarating music culture and sparked intense nationalism as nativist ethnocentrism vied with a progressive vision of America as a cosmopolitan participant in a broadly international community. Immigrating from Greece to the United States at the outbreak of the Great War, Sophocles Papas (1893–1986) emerged in 1920s Washington D.C. as an American authority on the European classical guitar. Through a series of columns and articles featured in prominent national music journals, Papas dialogued with fellow guitarist and writer Vahdah Olcott Bickford to position American guitar culture as the domain of elite and scholarly musical artists. Classicizing the history of the guitar by linking it to a distant and idealized past, Papas outlined a view of musical history that placed ancient Greek civilization at the creative center of a cosmopolitan musical world and protagonized Greece as the cultural progenitor of the guitar and indeed of Western classical music. In identifying a Greek origin for modern musical ideas and technology, Papas claimed a Greek hegemony in the early history of Western classical music. Papas’s strategy of classicization constructed space for Greek and other marginalized Euro-diasporic nationalities within the evolving milieu of intra-war American national identity by imagining a broad cultural ancestry from which diverse American musicians could claim common diasporic descent.

Keywords: Guitar History, Cosmopolitanism, Classicization, Diaspora, Vahdah Olcott Bickford, Sophocles Papas

Introduction

With the end of the Great War, a generation of young American men who had entered military service in 1917 came back restless to the riotous excursion of modern society. Influenza killed nearly a million Americans between 1918 and 1920, while the eighteenth and nineteenth amendments of 1919 ushered unprecedented social change, empowering women and sparking an underground culture of alcohol, crime, music, and revelry (Ostrander 1968, 343–344). Rural Americans migrated from farms into cities rapidly growing in population, industry, and cosmopolitanism. Large numbers of African Americans moved from the South to the North, sparking a new chapter in American music (Garrett 2008, 83). Young people embraced an irreverent counterculture that advanced sexual liberation to the sound of jazz music exploding in a recording industry that danced freely across racial lines (Garrett 2008, 6; Miller 2003, 13–14). The newly accessible stock market seemed to proffer wealth and rapid class mobility to any who cared to invest. The surging trade in prohibited liquor and a roaring stock market similarly promised easy money and the dream of vast overnight fortunes, yet crime and poverty remained rampant among industrial urban workers (Miller 2003, 35).

At the same time, conservative Americans balked as waves of newcomers rearranged the form and character of urban communities (Miller 2003, 26). Immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe arrived in unprecedented numbers, rising to over a million annually. World War I momentarily curtailed immigration and all but anathematized foreigners: nonnatives were considered so dangerous to national security that many, even including the most celebrated European musicians, were investigated, arrested, or deported (Clague 2022, 107–108). Wartime fear of outsiders accentuated a distrust of foreigners that predated the war and long outlived the armistice. Immigration rates spiked again immediately after the war, however, sparking nativist outrage (Xie 2025, 28–29). The widespread sense that immigrants were not assimilating (or from the nativist point of view were not fit to assimilate) engendered fears that both the ethnic and cultural makeup of the country would soon shift beyond recognition (Ickstadt 1993, 4).

This climate of suspicion and hostility by Americans towards southeastern Europeans was rampant by 1920 when Greek-born Sophocles Papas (1893–1986) settled in Washington D.C. to build a career in music. Born in Greece and a veteran of the Balkan wars, Papas arrived in America just in time for the Great War. After serving in the United States Army, Papas entered the music trade with a vigorous entrepreneurial spirit. Opening a music studio and styling himself a teacher of any fretted instrument, Papas eagerly embraced the heterogeneity of the American music scene but gradually aligned himself with a determined subculture within the profession that promoted the guitar as a medium for serious scholars of classical European art music. He would become among the most influential and respected teachers of classical guitar in America: a champion and confederate of the world’s leading classical guitarist Andrés Segovia, devout emissary of the Segovian style and technique, an apostle of the classical guitar as a conservatory instrument, and a musical missionary who pioneered guitar curriculum within the major degree programs of American universities. In the 1920s, however, the main concern for Papas, as for many southeastern European immigrants, was to fit into American Society (Fleegler 2013, 18–34).

Papas arrived at a time when many Americans looked dubiously at Greeks, judging what were called “new immigrants” as social and cultural outsiders (Anagnostou 2009, 51–52; Saloutos 1964, 238). Americans primarily imagined themselves linked by culture and identity to Western Europe—descendants of British, French, or Dutch colonies in North America. The founding mythology of America portrayed early settlers as Western European pilgrims, missionaries, and explorers. Western European ancestry was central to the collective sense of American nationality, but the position of Southern and Eastern Europe within this imagined identity was tenuous and suspect (Anagnostou 2009, 2; Anderson 1983). Papas therefore had every reason to emphasize that he was no cultural outsider, that his Greek heritage was central to a classical patrimony bequeathed to a Western world that included Europe and America.

To accomplish this goal, Papas began a campaign of research and writing to spotlight the importance of classical Greek music and art in the formation of European culture that culminated in his influential 1930 historical treatise “The Romance of the Guitar” first published in the music journal The Etude (Danner 1998, 31). For Papas, a recent cosmopolitan immigrant from Europe’s eastern fringe, social inclusion depended on framing American nationalism as the cultural descendant of a civilizational patrimony encompassing America and the entire West. Papas idealized American music as part of a globally dispersed classical culture stemming from Greece and forming a diasporic family of sibling cultures (Stokes 2008, 3–26). Pragmatically, classicizing Western cultural ancestry negotiated space within American nationalism for a broader array of ethnic identities, including his own.

Papas’s strategy of shifting nationalist perspective through the promotion of cosmopolitan classicization demonstrates processes described by prominent social theorists: Thomas Turino postulates that nationalism needs cosmopolitanism regardless of the inherent threat that it presents to native culture, and that cosmopolitan societies like 1920s America necessarily internalize through socialization myriad cultural practices and identities from abroad (Turino 2000, 15–16; Stokes 2008, 9). Turino’s theory of cultural reform describes a balancing act of a national identity paradoxically eager for and threatened by outgroup cultures, which are both dangerously foreign and necessary for survival. American nationalists who feared massive immigration as an existential threat nonetheless needed the idea that Papas presented: America as a richly cosmopolitan beacon of Western civilization.

Ethnomusicologist Michael Largey identifies “classicization” as a cultural strategy to downplay political or ethnic divisions in the present by emphasizing shared cultural connections to an imagined ancestral, idealized, and ahistorical past (Largey 2006, 18; Chatterjee 1993, 95–98). Papas argued for a broadly inclusive American identity by promoting what Largey terms “diasporic cosmopolitanism,” merging disparate ethnic and cultural interests by deliberately “adopting productive intellectual or cultural freight” from associated groups or cultures (Largey 2006, 18; Stokes 2008, 16). Papas intervened to cosmopolitanize the American guitar by locating classical guitar music within the diasporic lineage of Greek cultural influence both to foster respect for the Greek contribution to classical music and amplify recognition of classical Greek hegemony within the diaspora of European art music, thus negotiating tension between large-scale Western cosmopolitanism and local American distinctiveness (Largey 2006, 5; Turino 2000, 15–16). In the face of 1920s American nationalism, Papas positioned Greek identity at the root of European classicism, establishing the guitar as an emblem of the classical Greek thread running through the European cultural diaspora that would be the foundation of an American musical identity.

Drawing primarily on the work Turino and Largey, I argue that Papas’s writings engage contemporary American nationalism by tracing broad communal connections to an idealized past serving as the imagined cultural ancestor of twentieth-century America, thereby assuaging contemporary socio-political tensions and merging diverse ethnic interests and identities within American society (Largey 2006, 17–18). Papas’s strategy of locating traditions of classical guitar music within the lineage of classical Greek cultural influence amplifies recognition of classical Greek hegemony within the diaspora of European art music and illustrates Largey’s principle of diasporic cosmopolitanism through the deliberate adoption of distant intellectual traditions from related groups and the promotion the merged cultural interests among of disparate but related ethnic identities (Largey 2006, 18). Papas’s strategy of classicizing the culture of American guitar performance wove Greek identity into the fabric of European musical history by positioning Greeks as leaders and progenitors of a cosmopolitan Western classical music tradition and classical music itself as a cosmopolitan yet broadly Greek intellectual diaspora. Through his publications at the close of the 1920s, Papas created space for Greek identity in nationalized American culture by framing a classicized and cosmopolitan history of music within a diasporic narrative. By positioning Greece as the cultural progenitor of European music in general and of the guitar in particular, Papas helped construct a protagonistic role for Greeks in a long-unfolding European musical diaspora (Anagnostou 2004, 45–46).1 Papas’s classicization of the guitar proposed musical history itself as a part of the Greek diaspora, reflecting a strategy to integrate Greek identity within American cultural self-perception.

Life in the Cosmopolitan Diaspora

Sophocles Papas developed a cosmopolitan perspective as part of his upbringing. Born in Ioannina, a region of Greece then controlled by the Ottoman Empire, Papas inherited a lifelong passion for music, learning, and languages from his father, a college-educated schoolteacher (Miller 1936, 407; Smith 1998, 1). At age ten Papas went to live for five years with his uncle in Cairo, a multicultural cosmopolitan city where Papas would develop a deeply international worldview during his formative years (Smith 1998, 2). Ostensibly within the Ottoman Empire, Egypt was in fact controlled by the British and teemed with resident populations from all over the world, including a large and rapidly growing Greek community (Abu-Lughod 1965, 454–455; Karanasou 1999, 28–34). There Papas studied the mandolin, then the most popular instrument in Cairo, with a local music teacher who also taught Papas to speak Italian (Danner 1998, 29). Papas recognized language as a key to crossing cultural boundaries in the diverse neighborhoods of Cairo and soon became determined to learn as many languages as possible, gradually gaining competence in Italian, Arabic, English, and French (Smith 1998, 2; Danner 1998, 29).

In 1912 the nineteen-year-old Papas returned to Greece, where the outbreak of the Balkan Wars swept him into two years of fighting (Smith 1998, 3; Danner 1998, 29). Scarred physically and emotionally by the war, Papas was badly disillusioned when the Florence Protocol of 1913 placed his home in Northern Epirus within newly drawn boundaries of Albania (Heraclides & Kromidha 2023, 168; Smith 1998, 3). He left the country and sailed for America.

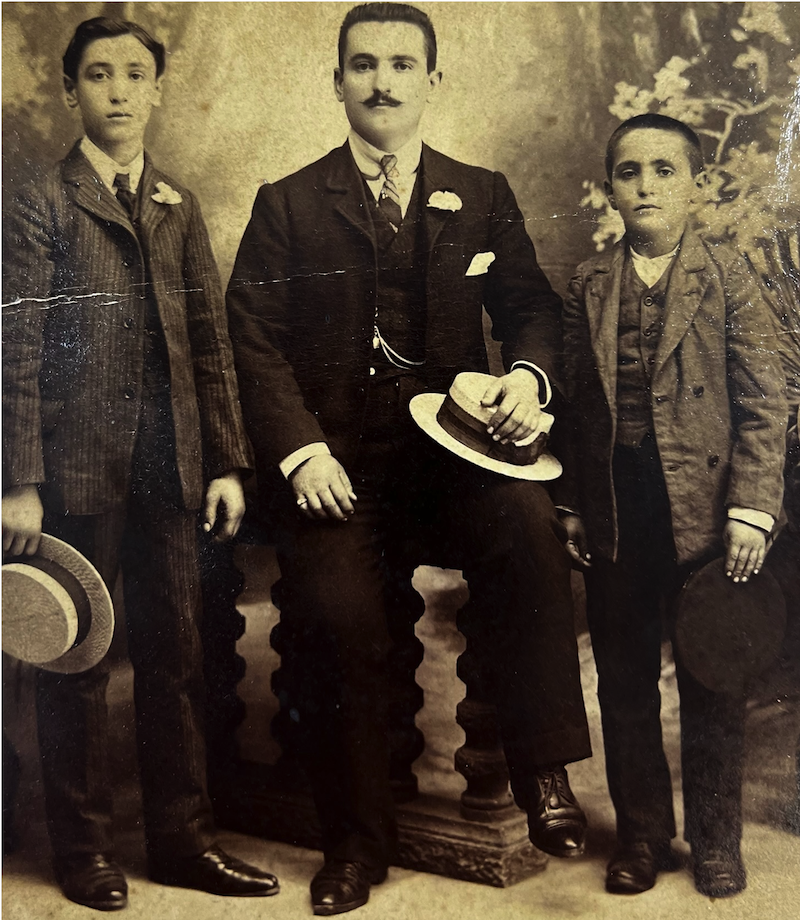

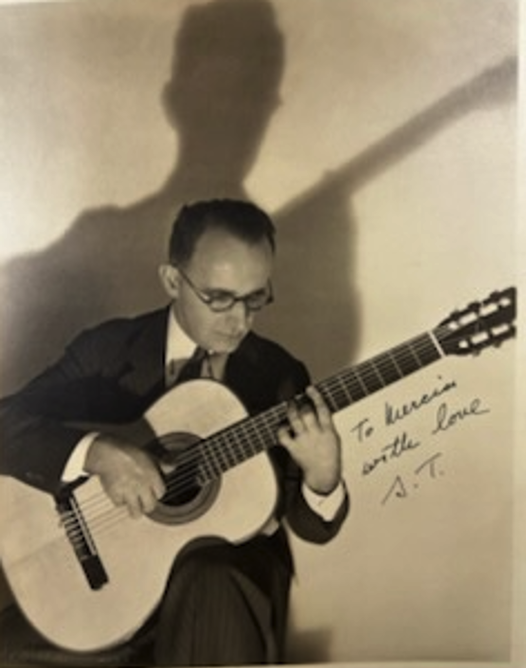

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Papas arrived in Massachusetts to stay temporarily with fellow expatriates who were living in Worcester, where he joined a hardworking and entrepreneurial Greek community (Kaloudis 2018, Kenny 2013, 13–16; Ramnarine 2007, 378–379; Smith 1998, 3). Although he departed Greece by himself, Papas was hardly alone in his decision to leave home. Violence and starvation that attended the breakup of the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century displaced thousands of Greeks from lands that their families had held for generations. Factory jobs in New England mill towns drew numerous diasporic Greeks of Papas’s generation, young men who formed small enclaves upon arrival but sought rapid integration within American society (Gage 1989, 42–46; Moskos 1980, 18). Encouraged by his new friends, it was not long before Papas decided to make America his permanent home.

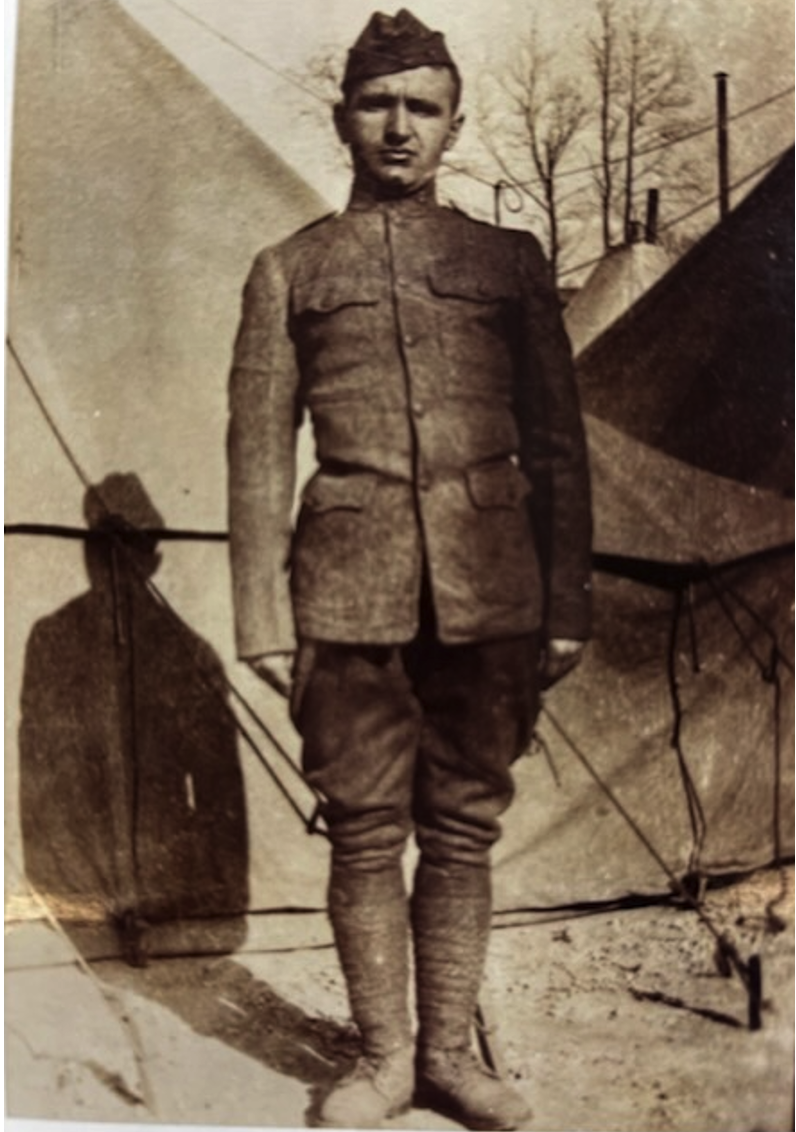

In the spring of 1917 America entered the First World War and the federal government incentivized military enlistment among immigrant men by facilitating naturalization in exchange for service in the armed forces. Papas, already a veteran of the Balkan Wars, took the opportunity to become both a soldier and citizen of his adopted country (Saloutos 1964, 234; Smith 1998, 3–5). Training with a mobile repair unit in the United States Army, Papas was invited to give mandolin performances for the entertainment and morale of his fellow soldiers (Dallman 1978, 12). Papas enjoyed the camaraderie of the informal concerts and discovered a natural confidence using music to connect with audiences. He decided that after the war he would seek a musical profession.

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Discharged honorably from the army in 1918 at age 26 and now a U.S. citizen, Papas soon settled in Washington D.C., working as a cashier in several Greek restaurants while building the foundations for a career in music (Smith 1998, 5). Papas slowly emerged from the closely knit family of Greek expatriates that had so far formed most of his friends in America (Dallman 1978, 33–34). Having gained fluent English from his time in the American army, he began to seek his fortune in a mainstream American society largely uncongenial to Greek immigrants.

Immigration and Identity

American nationalism in the early 1920s focused on race, and fears that a flood of foreigners from the South and East would calamitously transform their nation were rampant. As labor violence exploded, many Americans believed that foreign agitators intended another Bolshevik Revolution on American soil (Goldberg 1999, 66–88; MacDonald 1988, 236; Miller 1936, 34–50; Grant 1936, xxxiii). Widespread xenophobia found voice in popular contemporary books such as naturalist Madison Grant’s 1916 The Passing of the Great Race, Henry Ford’s anti-immigrant treatise serialized during the early 1920s as The International Jew, and Harvard Ph.D. Lothrop Stoddard’s 1920 The Rising Tide of Color. Stoddard’s theory of racially superior “Nordic” western Europeans besieged in American by encroaching sub-ethnicities was widely read and became immortalized through paraphrase by the character Tom Buchanan’s monologue in the opening chapter of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby:

“Civilization’s going to pieces,” broke out Tom violently. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard? . . . Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved” (Fitzgerald 1925, 18).

Nativist Americans imagined immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe as both as potential carriers of dangerous foreign ideology and threatening racial outsiders (Jacobson 1998, 68–83). Stoddard articulated the trepidation many Americans felt about mass immigration by eastern and southern European peoples:

Our country, originally settled almost exclusively by Nordics, was toward the close of the nineteenth century invaded by hordes of immigrant Alpines and Mediterraneans, not to mention Asiatic elements like Levantines and Jews . . . The immigrant tide must at all costs be stopped and America given a chance to stabilize her ethnic being (Stoddard 1920, 165; 265–266).

True to Stoddard’s vision, nationalist apprehension over immigration in the early 1920s spurred passage of The Congressional Emergency Quotas Act in 1921 and the 1924 Immigration Act, strictly curtailing the total number of immigrants and ensuring that most came from western Europe (Jacobson 1998, 88; Xie 2025, 28; Miller 2003, 147). Immigrants from Europe’s Eastern fringe, including Greeks, were much less welcome (Fleegler 2013, 34).

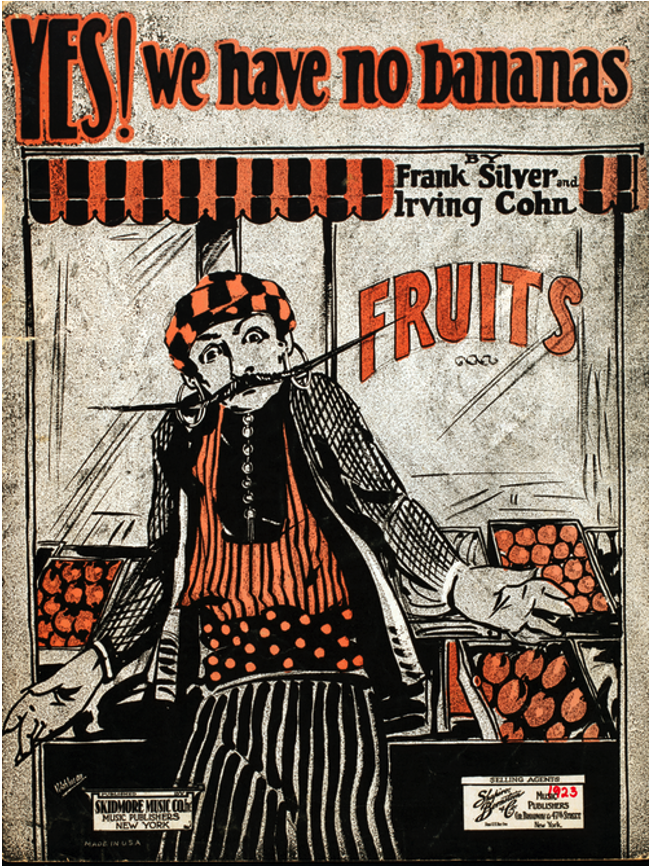

Greek Americans in the 1920s having only recently begun to arrive in large numbers, were particularly visible as exotic immigrants and tended to emblematize the suspicions and fears that Americans felt towards the new immigrants (Moskos 1999, 104–105). The song “Yes we have no bananas,” published by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn in 1923 quickly became one of the most popular songs in American history, in large part because of the strong social resonance of its mocking the foreignness of recent Greek immigrants:

There's a fruit store on our street

It's run by a Greek

And he keeps good things to eat

But you should hear him speak!

When you ask him anything, he never answers "no"

He just "yes"es you to death, and as he takes your dough

He tells you

"Yes, we have no bananas

We have-a no bananas today!”2

Interviewed by Time Magazinein 1923, Lyricist Frank Silver explained what he saw as the amusing genesis of his hit song: “About a year ago my little orchestra was playing at a Long Island hotel. To and from the hotel I was wont to stop at a fruit stand owned by a Greek, who began every sentence with 'Yess.'”3 The humor that Silver found in this ethnic stereotype evidently resonated with the cultural mainstream, for his lyrics playing on the hackneyed foreignness of Greek immigrants propelled the song to spectacular success—it remains among the most popular American tunes of all time.

A Music Entrepreneur

Far from dismayed by whatever xenophobia he may have encountered in Washington D.C., Papas wasted little time pursuing his dream of professional musicianship. Using money earned in local Greek restaurants, he bought a gut-stringed guitar and soon befriended two Italian mandolin players, Tony Delvecchio and Pasquale Romano, and together they arranged popular songs for their trio and hired out for weddings, dances, and other social gatherings (Dallman 1978; Danner 1998, 30). The gut strings and finger technique that Papas used on his guitar produced an unusual timbre—American guitars were usually strung with wire—and the group attracted audiences through the appeal of European exoticism (Huber 1994, 6–8; Smith 1998, 6–7).

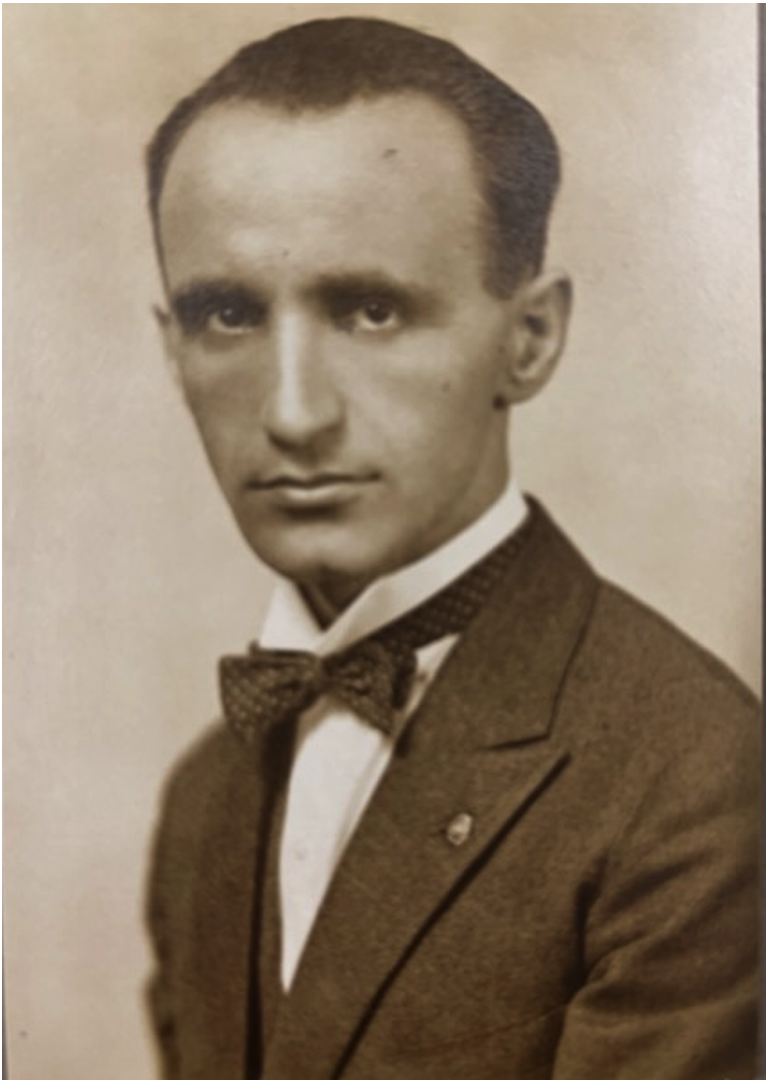

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

So far largely self-taught, Papas sought training in technique and the classical tradition to develop himself as an artist. He travelled to New York City for several lessons with William Foden, then the leading classical guitar teacher in America (Dallman 1978, 43). While in New York he befriended George Krick, a German guitarist and student of Foden. Papas and Krick conversed extensively about the availability of published guitar music, and Krick provided Papas access to his large personal collection of musical literature and a keen appreciation for the available printed repertoire. It was here that Papas encountered the extensive classical European guitar tradition in repertoire by such composers as Bach, Sor, Carcassi, and Carulli that would become his lifelong artistic obsession (Dallman 1978, 32–43).

Returning to Washington D.C., Papas began to offer short solo guitar performances at Droop’s Music Store at 13th and G St. NW—then a hub of musical activity and among the oldest and best-known music stores and performance spaces in the capital area (Christian 2016, 61; DeFerrari 2022). An intrigued audience member soon invited him to perform on the local radio station WJSV radio. Radio was then an exciting new technology, and Papas’s music resonated strongly with local audiences and led to more invitations and bookings of live performances around the D.C. area (Bathgate 2020, 82–89; Stewart 2005, 251). He soon had students clamoring for him to teach them to play the guitar in his gut-string finger picking style (Smith 1998, 7–8; Danner 1998, 30). Papas’s playing featured a sound that most Americans at that time had never heard: a guitar strung with gut and played with classical European finger technique. Intrigued audiences soon provided students to fill his studio, where Papas taught a wide variety of stringed instruments but preferred to guide his pupils towards what he saw as the higher musical path of classical guitar technique and repertoire (Noonan 2008, 166). Papas later recalled: “They came with a guitar with wire strings and a pick. So, I would start them to play some chords with a pick and wire strings. Then I would get my gut-string guitar and play for them and tell them, ‘There’s another way to play the guitar.’ Most of them were surprised and pleased” (Dallman 1978, 17).

(https://www.shorpy.com/node/15958)

In the 1920s Papas established his musical career by founding a teaching studio and vigorously promoting it through advertisement, radio, and local performances. He also engaged in networking with the diplomatic corps at the Greek and Spanish embassies to connect with prospective students (Smith 1998, 7–8). During the early 1920s Papas taught many stringed instruments, including the banjo, mandolin, and Hawaiian guitar, hoping to grow his business by satisfying popular demand as much as he could.

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Papas also took a position teaching at the nearby Robinson’s Music Store, where the company heavily advertised their private lesson services. This helped Papas became more widely known as a brilliant musician, teacher, arranger, and director (Smith 1998, 9). Papas was able to reach across cultural lines to attract students, working closely with immigrant communities, because he was multilingual and could easily teach students who spoke languages other than English (Smith 1998, 9). Many of his early students were from the Greek community and were referred to Papas by employees at Droop’s Music Store or by personnel at the Greek or Spanish embassies (Smith 1998, 8). Since the classical European repertoire that Papas taught in his studio was hard to find in America, Papas resorted to borrowing copies and arranging editions obtained from George Krick in New York. Papas promoted the classical tradition as far superior and considered the popular dance music abundantly published in America to be “terrible stuff . . . awful music” (Dallman 1978, 45). Although willing to help students learn whatever style of music they preferred, Papas insisted on the ideal of classical music in his studio.

Papas’s ideological commitment to the artistic supremacy of European classical music only deepened in 1926 when he married his first wife, Eveline Monico Hurcum, a British concert pianist (Dallman 1978, 15). She was a music teacher at National Park Seminary, and he met her through his performances at that school. With his marriage Papas largely emerged from the shelter of the Greek diasporic community that had been his closest friends in America. Papas and his wife, both Europeans and classical musicians, moved in the circles of the educated gentry of Washington. Papas found even this erudite society largely unaware of the European classical guitar tradition; his promotion within the community of the classicized guitar as an emblem of elite European musical culture was well received (Dallman 1978, 22–24).

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

By the middle of the 1920s Papas managed a large teaching studio and was a leading advocate for classical art music in the Washington D.C. area, giving frequent live performances (Smith 1998, 22). These gatherings brought together people from many nations and diverse cultures, often including distinguished citizens and international diplomats. Papas doggedly gave performances throughout the community and especially in public, private, and parochial schools throughout the area, including the prestigious National Park Seminary and the Hendley-Kaspar School of Musical Art (Smith 1998, 11). By 1926 Papas was in high demand as a popular radio performer having given more than fifty live concerts on air. He was famous throughout the Washington D.C. area as a lone advocate of classical European finger technique on gut guitar strings that struck American audiences as exotically European (Sharpe 1963, 3–24; Smith 1998, 13–14). Wireless performances helped Papas deliver his classical message to a wide audience as he became a well-known star of the nascent Washington D.C. radio scene. In February 1928 the music journal Crescendo took notice of Papas’s burgeoning career:

One of the popular young men in Washington today and prominent in the Capitol’s music circles is Sophocles T. Papas, teacher, and artist of fretted instruments. He has established a large studio in the exclusive section of the city and numbers many dignitaries among his pupils. He is instructor for fretted instruments at the National Park Seminary, an exclusive school for girls, which is one of the few schools to include the study of banjo, mandolin, and guitar in their regular course. Mr. Papas is also a faculty member of the Hendly-Kaspar School of Musical Art; he has also a wide reputation as a broadcasting soloist (Danner 1998, 32).

Papas viewed such publicity not only as an opportunity to build and develop an audience but as a chance to proselytize his view of classical music as an ineffable art form and the proper domain of serious artist-scholar musicians.

By 1928, Papas had a large and growing collection of published guitar music in his studio library that would provide the core repertory for his school of guitar (Danner 1998, 30). This was the canon of mostly classical music that he used for his own practice and for teaching his students (Smith 1998, 8). Papas mastered this material through frequent use and soon began to consider it insufficient for his school of classical guitar. Frustrated at being unable to find enough printed music to expand his studio library, Papas began to make his own arrangements of classical music for the guitar. He had these arrangements printed and bound for the use of himself and his students, and for sale in his music studio to any musicians looking for new guitar repertoire. This was the beginning of one of his most successful business enterprises and one that would have a great impact on the musical world around him: a publishing firm that he called the Columbia Music Company. Through this venture Papas would reach a broad musical public and heavily influence the practice and teaching of classical guitar throughout the United States (Stevens 2017, 13; Noonan 2008, 169; Smith 1998, 8–20).

In 1928, Papas’s passion for European classicism was electrified by an encounter with the great Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia, whose debut performance in New York inspired Papas to the technique of plucking the strings with long fingernails expressly grown for that purpose, rather than using the flesh of his fingertips as he had always done before (Turnbull 1974, 111). Papas and Segovia quickly became fast friends and Papas became an outspoken proponent of Segovia’s approach. He readily adopted aspects of Segovia’s finger technique and wholly adopted what he saw as Segovia’s masterful style and interpretation of classical music (Danner 1998, 31).

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Papas admired Segovia’s technique and broad pallet of tone colors. He was immediately converted and would subsequently present himself and his students as practitioners of the Segovian style (Smith 1998, 33). Segovia’s manner of playing the guitar would become globally influential, thanks in part to Papas early adoption and subsequent lifelong promotion of the Segovia’s technique and musical philosophy (Stevens 2017, 13; Noonan 2008, 169; Wade 2001, 131; Duarte 1998, 82).

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Classicizing the Classical Guitar

Papas took up writing to advocate classical music to American culture as a crucial element of the civilizational legacy bequeathed by ancient Greece to the Western world. He launched his career as a musical writer in March 1929 with a monthly column in The Crescendo, and a series of articles on guitar history in other journals published over the following year. Crescendo introduced Papas in the February issue with an article establishing his credentials as an elite musical artist. The piece described Papas as “a very prominent guitarist of the finest type” and highlighted his recent performance at the Newcomer Club in Washington D.C. in front of celebrities and international diplomats, including His Excellency Charalambous Simopoulos, Minister of Greece. The program was of “classical compositions, including Variations on a Theme by Mozartby Sor arranged by that renowned guitarist, now touring the country, Andrés Segovia; a Prelude by Chopin, and Caprice by Ernest Shand” (Crescendo, Feb. 1929, 24). This introductory review not only served to present Papas to the reading public but positioned him as scholarly musical classicist with credentials among the social elite, framing his close contact with high European culture as both an asset and a qualification.

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Papas used his monthly column to decry popular decadence in American music and idealize an elite tradition of European art music governed by rigorously high standards. In assuming his role as guitar writer at Crescendo, Papas replaced long-time columnist Vahdah Olcott Bickford—an erudite musician and passionate proponent of the classical guitar. Papas deeply admired Bickford and took her writings very seriously. He esteemed her as a colleague and fellow artist, recommending to his readers several of Bickford’s publications, and praising her as the only classical guitarist at the time besides Andrés Segovia to have made recordings of pieces for solo guitar and with piano accompaniment (Crescendo, April 1929, 24; May 1929, 17). In the August 1929 edition of Crescendo, Papas excoriated a reader for comparing the recordings of a popular guitarist to those of Segovia and Bickford, retorting that Segovia and Bickford were true and scholarly artists of the guitar, and as emissaries of classical artistry were markedly distinct from popular musicians. He wrote of Bickford: “from her writing I can judge her standard; and if we may only have one Segovia, there are many who have the same high artistic standard, regardless of whether they are able to attain it or not” (Crescendo, August 1929, 15). For Papas, the classical culture of guitar performance was a domain available to any who choose to devote themselves to high art. Musicians electing any lesser path were excluded. Papas considered Bickford a rare and serious artist, equal to Segovia in vision and integrity, and among the true and great artists. Papas’s willingness to defend, promote and even compare her favorably to Segovia speaks to the level of his admiration. Papas studied and admired Bickford’s widely influential 1921 Method for Classic Guitar, an exemplary musical textbook introducing progressive technical studies to students through classical selections and compositions by Bickford herself (Dallman 1978, 38,90; Bickford, 1921).4

Bickford’s Method began with “A Brief History of the Guitar” that must have struck Papas as incomplete as it contained almost no reference to Greece. Conflating zither- and lute-type chordophones, Bickford discussed the antiquity of the guitar, tracing its history to the Fourth Egyptian Dynasty and declaring it “the best-known of all” stringed instruments. She identified the guitar as a direct descendent of the Arabic Oud, considering it a conglomeration of Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, and Hebrew archetypes.5 Bickford primarily saw the roots of the guitar spreading from the middle East, omitting any significant Greek cultural influence on the instrument’s development.

Papas’s first major prose publication, the 1929 article “Trailblazers of the Guitar” published in the journal Mastertone,seems obliquely to engage Bickford’s “Brief History” by reframing the origins, development, and socio-historical context of the guitar and its ancestors as Greek. “Trail Blazers of the Guitar” heralds Papas’s career as a writer on musical history, appearing in monthly installments during March, April, and May 1929, and coinciding with Papas’s March debut as the guitar columnist for Crescendo. The editor of the journal introduced Papas as a “widely known teacher, composer, and publisher,” praising the article itself as a “splendid and authoritative history of the guitar” and “among the finest and most interesting articles we have ever published,” urging readers to give the article their fullest attention (Smith 1998, 195).

“Trailblazers of the Guitar” located the history of Western music within the provenance of Ancient Greek culture. The article began with a blunt assertion that Socrates, the great philosopher of the Athenian Golden Age, played the guitar. Papas declared that even in Socrates’s time the guitar was ancient, and dated the original guitar to 4,000 B.C. in Egypt, tracing its introduction to Greece after the Trojan War, or about 1,000 B.C. where it found its modern etymology, pointing out that the modern name of the instrument is itself a Greek word (cithara). Papas associated the guitar with the rhapsodic poets and specifically with Homer, Terpander, Themistocles, and Episcles of Hermione, as practitioners and virtuosi, declaring the playing of the instrument “much sought after by the Athenians.”6 This strategy of selective tradition, a form of cultural memory based on the recombination of carefully chosen historical anecdotes, served Papas as a frame to construct historical narrative emphasizing the context of Greek cultural hegemony (Williams 1977, 115–122).

Musical journalism gave Papas a crucial opportunity to classicize the guitar for wide American readership. In March 1929, the same month that “Trailblazers of the Guitar” was published in Mastertone, Papas used his guitar column at Crescendo as a salvo for the classicization of American music. Papas declared from the outset a new age of American culture, demanding “the better class of music,” meaning the canonic repertoire of European classical art music, particularly as interpreted, arranged, and performed by Andrés Segovia (Noonan, 166–167). Papas asserted that Segovia’s American performances have “made the public better able to understand and appreciate” classical music and hoped that his column might further engage readers in studying “the construction and character” of the music of great classical composers in and help guitarists “interpret their works correctly and with proper effect” in order to “establish a greater understanding and appreciation” of the great classical masters.

By positioning Segovia withing a pantheon of great European masters, Papas aimed to apotheosize European classicism itself as the ultimate artistic goal for culturally aware American musicians. The April 1929 issue of Crescendo celebrated Segovia’s induction into the American Guild of Banjoists, Mandolinists, and Guitarists in Boston on March 15, 1929 (5, 7). An editorial titled “Andrés Segovia Presented with First Honorary Membership to the Guild: Encourages Movement for Finer Music,” both conveyed Papas’s adulation for Segovia and implemented his classicization strategy by modeling European art music as the proper domain of self-respecting American musicians. The editorial extolled Segovia as a global superstar, “this celebrated guitarist has for the past seven or more years been exciting the various European capitals by his guitar performance . . . here is an artist who, without a doubt, stands in relation to the instrument of his choice as Casals does to the cello, and Heifetz to the violin” (Crescendo, April, 1929, 5). For Papas, Andrés Segovia represented the epitome of the classical artistry to which all others should aspire.

Papas cast Segovia’s ongoing American concert tour as part of a proselytization campaign to spread musical enlightenment across America ( Crescendo, April 1929, 17). He noted that Segovia’s frequent performances of classical music in American cities have “raised the guitar to its proper place in the musical world (Crescendo, April 1929, 17). Arguing that Segovia’s influence “upholds the prestige of this instrument,” for the “establishment of the guitar as an instrument fully worthy to interpret the works of the great masters,” Papas encouraged guitarists to embrace, like Segovia, classical art through “assiduous study and ever keeping before us the highest ideals” (Crescendo, April 1929, 17). Invoking the Greek cultural foundations of Western classicism, Papas cited the philosophy of Socrates: “all I know is that I know nothing” to admonish guitarists selflessly and tirelessly to devote themselves to the goal of mastering European classical guitar repertoire. Papas designated Segovia “one of the greatest living artists on any instrument,” and “unique in his art therefore beyond comparison,” and proposed that American musicians draw artistic energy from his exemplary performances and recordings (Crescendo, May 1929, 20).

For Papas, no higher purpose existed than situating the musical culture of the American guitar within the civilizational context of European classicism. His August 1929 column simmered with ire stoked by a reader’s careless comparison of Andrés Segovia to popular steel string and plectrum guitarist Nick Lucas. Papas responded by slinging scornful contempt on “mushy” popular music performed by mawkish entertainers:

Segovia could not take Nick Lucas’ place and make people mushy, any more than Kreisler or Rachmaninoff could. It is amusing to me […] to class Segovia with Nick Lucas […] Segovia’s technique is transcendent, and this means beyond criticism […] There are several great guitarists giving concerts in Europe today, but even there, according to the critics of England Germany, Spain, France, Italy and Austria, Segovia is something unique, not only among guitarists, but the great artists of all instruments (Crescendo, Aug. 1929, 15; Noonan 2008, 168).

Papas saw Segovia as a model of classical excellence, his image as a devoted and uncompromising artist became a bludgeon for Papas to wield in the service of his agenda to classicize the American guitar, advancing elite European classical guitar tradition over and above popular American forms, superseding and belittling them in terms of cultural meaning.

Papas invited American guitarists to collective membership in an elite international diaspora of European classical music through the cosmopolitan classicization of guitar practice. His inaugural column focused on analyzing Fernando Sor’s Variations of a Theme of Mozart, which Papas had performed to critical recognition only the previous month at the Newcomers Club in Washington D.C. The detailed advice that Papas offered regarding the approach to practicing and performing each variation of this piece revealed him to be a very serious and thoughtful artist. Papas prioritized musical classicism by declaring: “Silk and gut are the only strings which should be used for solo work. Although wire strings are capable of producing considerable noise, with gut strings a truly musical tone and volume can be obtained with a little effort and practise [sic]. . . we strongly advise all guitarists to use silk and gut strings if they wish to impress the public with the fact that they are playing an instrument capable of great beauty of tone and nuance (Crescendo, March 1929, 26). His European spelling of the word “practice” tantalized American guitarists with the prospect of induction into a high society of pan-European classicism.

Papas considered American musical culture to be legitimate to the extent that it descended, however distantly, from what he imagined as a broadly inclusive classical European past. In June 1929, Papas gave a critical review of the musical performances at the recent convention of the American Guild of Banjoists, Mandolinists, and Guitarists. Papas endorsed the artistic diversity of the program, including arrangements of both classical and popular compositions for such ensembles as the Baltimore Mandolin Orchestra, Gebelein’s Hawaiian Guitar Troupe, and the Nordica String Quartet. Papas was impressed by virtuoso solo recitals by guitarist William D. Moyer, and banjoist Frank Bradbury, but criticized the inclusion by some performers of what he considered insubstantial or frivolous musical choices. He admonished the convention managers to be “a little more discriminating in their arrangement of programs” in order appropriately to “elevate” the musical tone of the event (Crescendo, June 1929, inside back cover). Clearly disappointed by the paucity of classical guitar repertoire, he sharply lamented the cancellation of George C. Krick’s classical guitar lecture recital—calling it “one of the greatest disappointments of the convention” (Crescendo, June 1929, inside back cover). Papas found it maddening that the conference business session ran over the time that Krick had been scheduled to perform. For Papas, this unforgivable misplacement of priorities assaulted the convention’s very purpose—to promote European classical music as the defining ideal that contextualized the entire program. Papas objected that Mr. Krick’s recital would have displayed “the most difficult and beautiful solos of the great masters which are rarely heard, and this would have been not only a great source of enjoyment but education as well” (Crescendo, June 1929, inside back cover). He had been counting on Krick’s performance to classicize the program, thereby linking all participants to an idealized musical tradition.

Papas advocated the pursuit of absolute classical music, recommending it to every guitarist as a means of self-improving study of musical classicism. In his October 1929 column he urged every American guitarist to study classical repertoire with particular focus on absolute music of the sonata genre:

There must be many guitarists who are not familiar with the sonata and are under the impression that this type of composition is high-brow and dull, and, due to this misapprehension, they are missing a great deal of musical joy. The sonata is the highest form of composition and a little study would enable them to understand its character and construction and open up a new realm of musical beauty […] ambitious students have plenty of opportunity to familiarize themselves with the sonata by obtaining the works of this type of any of the great masters, especially those of Beethoven, many of whose sonatas are recorded for the Ampico [i.e. piano roll] or the phonograph. They can also attend symphony concerts, for the symphony is a sonata written for orchestra (Crescendo, October 1929, 13).

Papas found virtue in knowledge of classical literature, rather than the technical mastery of performance, believing that every listener gains artistic understanding, every audience joins a timeless community of musical scholars by assisting in the ritual performance of classical music.

Papas’s most influential work on musical history, an extended article titled, “The Romance of the Guitar” published as a series in April, May, June, and July in 1930 in the musical journal The Etude, foregrounded the ancient Greek roots of classical music. This publication effectively crowned Papas’s writing career, as Crescendo abruptly suspended individual instrument columns in favor of a conglomerated mailbag format immediately after the stock market crash in November 1929 (Danner 1998, 31–32). “The Romance of the Guitar” required considerable research and a substantial investment of time and Papas considered it the best writing on guitar history yet published in America (Dallman, 1978, 57–58). The lengthy multi-partite article pioneered the extensive and serious treatment of the guitar in a widely read national music magazine (Dallman, 118 n.15). It would be repeatedly reprinted over the course of decades in a variety of musical journals (e.g. Music Studio News 1956, and Frets 1959), becoming a widely available historical reference for generations of readers, guitarists, and music students. The Special Collections Library at George Mason University retains historical term papers written by college students pursuing degrees in guitar with Papas or Shapiro at American University during the 1960s that rely heavily on “The Romance of the Guitar” as a historical source.7

Like Papas’s earlier musical history “Trailblazers of the Guitar,” “The Romance of the Guitar” obliquely dialogued with Vahdah Olcott Bickford’s “Brief History of the Guitar,” confirming some elements of her assessment while arguing that the development and history of the guitar are substantially original to ancient Greek culture. The body of “The Romance of the Guitar” identified the instrument’s Greek roots, beginning with a section called “Remote Ancestors of the Guitar” (Etude, April 1930, 252).8 Papas explained that the name of the instrument itself is Greek—“kithara” in Greek, “chitarra” in Italian. The ancient Greek “cithara” was, according to Papas, an archaic guitar and the organological predecessor of the modern instrument. He wrote, “in the Hymn to Mercury, ascribed to Homer, Mercury and Apollo are said ‘to play with the cithara under their arms,’” proving that the instrument was in fact a guitar and not a harp. Papas located the origins of the guitar in antediluvian antiquity, speculating that the guitar arrived in Greece “shortly after the Trojan war, about 1,000 BN.C., and was used ty the rhapsodists” (Etude, April 1930, 300). Papas claimed that Homer sang his Iliad and Odessey to the accompaniment of the kithara, and that classical Greek literature is full of references to this instrument—making it central to Greek culture in its Golden antiquity. Papas cited the legend of Thamyris, so accomplished a guitarist that he sought to rival the muses themselves, and recalled a poem by Pherecrates that describes a four-stringed guitar played with complex technique and expressive in twelve musical modes. He interpreted the poem as humorous evidence that this complex guitar music must have been originally received as controversially modernist, indicating the innovative nature of classical Greek musicians.

Papas argued that the most crucial developments in guitar history took place in ancient Athens. He identified specific figures of classical Athenian history as students of the guitar, crediting the virtuoso Terpander with improving and advancing the technology and technique of the ancient Athenian instrument (Etude, April 1930, 300). In the chapter titled “Socrates Takes Lessons,” Papas observed that during the fifth-century B.C., known as the Golden Age of Athens, “the guitar was held in high esteem by all classes of Athenians,” including the leading statesman Pericles, the celebrated philosopher Socrates, and the great general Themistocles. Papas identified prominent virtuoso teachers honored by Athenians, including Damon and Episcles of Hermione.

Papas emphasized that Roman music was essentially Greek music transplanted, that many enslaved Greek musicians were forced to move to Rome, and that Rome essentially pillaged musical culture from Greece (Etude, May 1930, 517). In the section titled “Nero’s Prizes,” Papas argued that culturally ambitious Romans, including the Emperor Nero (A.D. 66) went to Greece explicitly to expropriate art and music, returning to Italy with eminent musicians. These became celebrated performers and teachers of music in Rome, transferring the musical science, art, and technology of classical Greece into the Roman world, where it became the model of art music in Western Europe and the Mediterranean world. Papas spotlighted Diodorus, the great guitarist, as an example of a Greek musician taken to Rome who subsequently taught the science of music to the Romans.

Papas argued that Greek music moved through Rome to became central to Christian culture. He postulated that traditions of classical music travelled throughout the Western world with Christian liturgical practice, led by Greek ecclesiastical musicians such as Clemens Alexandrinus (ca. 150–ca. 215) and Eusebius (ca. 260–ca. 239) who designed Christian hymns for congregational voices accompanied by kithara. Thus, the guitar and the musical knowledge of ancient Greece became the foundations of classical music of throughout Christendom through the dissemination of musical liturgy. For Papas, Western music arose in Greece and then migrated to Rome, moving throughout the Western world with Christianity (Etude, May 1930, 517).

(George Mason University Special Collections, Papas Papers, Box 40,

reproduced with permission).

Conclusion

While American nationalism in the 1920s engendered mistrust of cultural influence from the fringes of Europe, it also sought self-legitimacy through cosmopolitan connections to a broader and older foundation of culture and civilization. Immigrants perceived as non-Western posed a threat to nationalist imaginings of America as a cultural outpost of Western Europe. Papas’s writings constructed a system of inclusion for Greeks and other marginal ethnicities by strategically classicizing musical culture through a broadly diasporic and cosmopolitan lens, proposing mutual respect through common cultural ancestry rather than an ethnic one.

Papas positioned Greek culture as the founding contributor to the cosmopolitan history of the classical guitar. His experience reflects strategies of diasporic Greeks to integrate and influence American cultural self-perception at a time of American emerging internationalism, centralizing Greek musical contributions and to present musical history itself as a form of Greek diaspora. Papas employed a strategy of musical classicization, weaving Greek culture into the diasporic fabric of European musical history and positioning Greeks as leaders and progenitors of a cosmopolitan classical music tradition, while simultaneously reassuring the Western identity of an adolescent American musical culture.

October 23, 2025

Nicholas Ezra Field is Assistant Professor of Musicology at Michigan State University. His research focuses on the history of European music of the Early Modern period and American music of the twentieth century. He writes and teaches on the cultural intersections of music and patronage, nationality, traditionalism, cosmopolitanism, religion, and modernity.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Michael Largey, Mark Clague, Larry Field, and Sean Field for their comments on early drafts of this article. Thanks for the kind assistance of Mieko Palazzo at the Special Collections department of Fenwick Library at George Mason University, and Andrea McMillan at the Special Collections department of the Michigan State University Library. Travel to the Sophocles Papas archives at George Mason University was made possible by a grant from the Michigan State University College of Music.

Works Cited

Abu-Lughod, Janet. (1965). “A Tale of Two Cities: The Origins of Modern Cairo.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 7/4: 429–57.

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. (2009). Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

________. (2004). “Forget the Past, Remember the Ancestors! Modernity, ‘Whiteness,’ American Hellenism, and the Politics of Memory in Early Greek America.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 22 (May): 25–71.

Anderson, Benedict. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

Bathgate, Gordon. (2020). Radio Broadcasting: A History of the Airwaves. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Bickford, Vahdah Olcott. (1921. Reprinted 1964). Method for Classic Guitar. New York: Peer International Corporation.

Chatterjee, Partha. (1993). The Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Christian, Rachel. (2016). “William Metzerott and the D.C. Music Trade.” Washington History 28/2 (Fall): 54–63.

Clague, Mark. (2022). O Say Can You Hear: A Cultural Biography of the Star-Spangled Banner. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Dallman, Jerry. (1978). Guitar Teaching in the United States: The Life and Work of Sophocles Papas. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Guitar Society.

Danner, Peter, ed. (1998). “Papas on Papas with Reflections on Segovia.” Soundboard 25/1: 29–32.

DeFerrari, John. (2025). “Pianos and the Golden Age of D.C. Music Stores.” (Accessed Sept. 28, 2025). http://www.streetsofwashington.com/2020/01/arthur-jordan-and-homer-kitt-washington.html

Duarte, John W. (1998). Andrés Segovia, As I Knew Him. Fenton, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications.

Heraclides Alexis, and Ylli Kromidha. (2023). Greek-Albanian Entanglements Since the Nineteenth Century: A History. London: Routledge.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. (1925). The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Fleegler, Robert L. (2013). Ellis Island Nation: Immigration Policy and American Identity in the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ford, Henry. (1920-1922). The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem. Dearborn, MI: Dearborn Publishing Company.

Gage, Nicholas. (1989). A Place for Us. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Garrett, Charles Hiroshi. (2008). Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grant, Madison. (1916. Reprinted 1936). The Passing of the Great Race or The Racial Basis of European History. Fourth Edition. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Huber, John (1994). The Development of the Modern Guitar. Westport: The Bold Strummer Ltd.

Ickstadt, Heinz (1993). “Trans-national Democracy and Anglo-Saxondom: Fears and Visions of a Dominant Minority in the 1920s.” In Ethnic Cultures in the 1920s in North America, edited by Wolfgang Bindor, 1–16. New York: Peter Lang.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye (1998). Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kaloudis, George. (2018). Modern Greece and the Diaspora Greeks in the United States. New York: Lexington Books.

Karanasou, Floresca. (1999). “The Greeks in Egypt: from Mohammed Ali to Nasser, 1805–1961.” In The Greek Diaspora in the Twentieth Century, edited by Richard Clogg, 103–19. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Kenny, Kevin. (2013) Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Largey, Michael. (2006). Vodou Nation: Haitian Art Music and Cultural Nationalism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

MacDonald Stephen C. (1988). “Crisis, War, and Revolution in Europe, 1917–23.” In Neutral Europe between War and Revolution 1917–23, edited by Hans A. Schmitt, 235–51. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Miller, Nathan. (2003). New World Coming: The 1920s and the Making of Modern America. New York: Scribner.

Miller, William. (1936). The Ottoman Empire and its Successors, 1801–1927. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moskos, Charles C. (1980). Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

________. (1999). “The Greeks in the United States.” In The Greek Diaspora in the Twentieth Century, edited by Richard Clogg, 103–19. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Noonan, Jeffrey J. (2008). The Guitar in America: Victorian Era to Jazz Age. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

Ostrander, Gilman M. (1968). “The Revolution in Morals.” In Change and Continuity in Twentieth-Century America: The 1920s, edited by John Braeman, Robert H. Bremner, and David Brody, 323–50. Athens, Ohio: Ohio State University Press.

Plutarch. (1889). Lives of Illustrious Men. Translated by John Dryden. Troy, NY: Nims & Knight.

Ramnarine, Tina K. (2007). “Musical Performance in the Diaspora: Introduction.” Ethnomusicology Forum 16/1: 1–17.

Saloutos, Theodore. (1964). The Greeks in the United States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sharpe, A. P. (1963). The Story of the Spanish Guitar, 3rd ed. London: Clifford Essex Music Co. Ltd.

Smith, Elisabeth Papas. (1998). Sophocles Papas: The Guitar, His Life. Chapel Hill: Columbia Music Company.

Sophocles Papas Collection, Fenwick Library Special Collections Research Center SCA C0052, George Mason University, Fairfax VA.

Stevens, Andreas. (2017). “Andrés Segovia’s Unfinished Guitar Method: Placing His ‘Scales’ in Historical Context.” Soundboard Scholar 3: 13–23.

Stoddard, Lothrop. (1920. Reprinted 1922). The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Stokes, Martin. (2008). “On Musical Cosmopolitanism” Macalester International 21: 3–26.

Turino, Thomas. (2000). Nationalists, Cosmopolitans, and Popular Music in Zimbabwe. Chicago. The University of Chicago Press.

Turnbull, Harvey. (1974). The Guitar from the Renaissance to the Present Day. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.

Wade, Graham. (2001). A Concise History of the Classic Guitar. Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications.

Williams, Raymond. (1977). Marxism and Literature. New York: Oxford University Press.

Xie, Bin. (2025). “The Aggregate and Distributional Effects of Immigration Restrictions: The 1920s Quota Acts and the Great Black Migration.” Journal of Comparative Economics 53: 25–55.

Notes

1 Papas’s strategy closely aligns with contemporary tactics employed by the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association. See Anagnostou (2004, 38–50).

2 https://genius.com/Louis-prima-yes-we-have-no-bananas-lyrics. Accessed July 30, 2025.

3 Frank Silver, interviewed in Time Magazine, 2 July 1923.

https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,715996,00.html

4 These items are stored in Box No. 11 and another box labeled “Papas U.S., England, Argentina,” Papas Collection at George Mason University.

5 Bickford related the guitar to a Greek instrument called the kisapa, as well as the Hebrew nebhel—the instrument she believed originally to have accompanied the biblical psalms.

6 The first-century Greek historian Plutarch names Episcles of Hermione as a prominent Athenian guitarist and a teacher of Themistocles. See Plutarch, Lives of Illustrious Men (Troy, NY: Nims & Knight, 1889, 197).

7 Box 17 of the Papas Collection in the GMU Special Collections Library.

8 The introductory paragraphs of “The Romance of the Guitar” proclaim the extraordinary expressiveness of the guitar as a self-accompanying polyphonic instrument, spotlighting Andrés Segovia as the greatest living proponent of the instrument.