Arrangement in Black and Gray

After Whistler

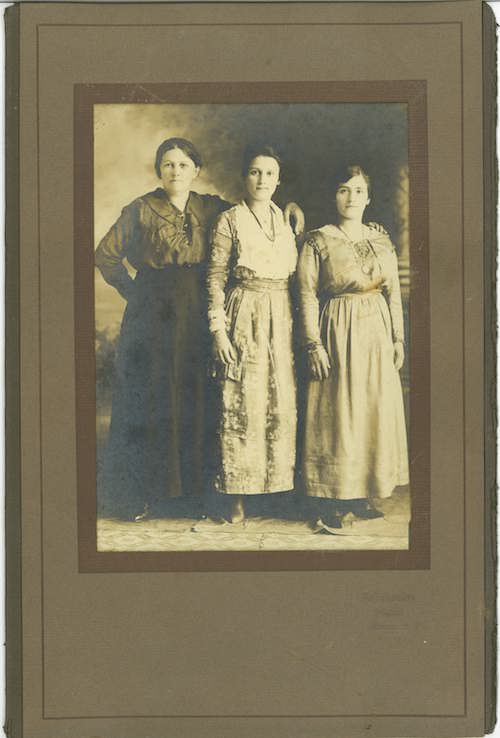

Manna Eleni, Mother, Midwife, Grandmother

Μάννα Ελένη, Μάννα, Μαμή, Μάμμη

A black-clad, somber midwife,

a faith healer with a mending touch,

my great grandmother, Manna Eleni,

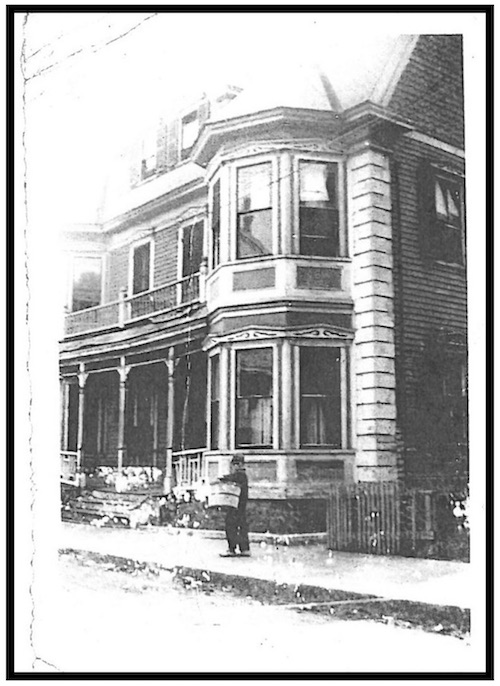

bought herself a house,

a thing unheard of at the time

for a woman émigré.

Cash down, no questions:

years of scrimping, toil and handiwork.

The house—ornate, imposing,

visibly Victorian

yet somehow gothic—

sprawled three stories high.

Built from fine New England wood,

somewhat pretentious

for a mill town—

High Victorian Italianate—

an architecture strange and new.

But Manna Eleni knew houses.

Born into a town of master builders—

Langhadia—nestled in Arcadia’s

myth-drenched mountains,

populated by itinerant stone masons,

men who built the towns and squares

of newly liberated Greece,

a motherland she’d never see again.

Back then, while master craftsmen made their rounds,

she started honing her own craft,

a self-apprenticeship in healing,

combing valleys, fields and hills

for herbs and flowers.

Ancient practices and tricks:

setting bones, applying salves,

tying mystic knots in handkerchiefs,

blood cupping with the flamed ventouza,

memorizing charms and murmuring prayers,

reciting scripture, uttering mild spells,

warding off the “evil eye”

—ο βάσκανος οφθαλμός, το μάτι.

ΙΙ

Excelling at her occult craft,

too good, in fact, at curing,

the dank, cramped immigrant slums of Lowell

knew her healing presence.

Lowell—city of mills and factories—

where cotton dreams could spin out of control,

weaving nightmares,

where industry and danger

vied for your very limbs

(her husband’s leg lost in a tanning mill).

Lowell—on the banks of the Merrimack

where Manna Eleni settled

after navigating Ellis Island.

“Venice of America,”

city of canals by whose granite flanks

so many sat and wept

remembering abandoned Zions.

America, America…

bricks, cogs, smoke stacks,

the warp and weft of dreams

and disillusion.

Applying there her healing,

Eleni’s cupped ventouzas

would soon became vendettas.

The local doctors—

hypocrites who forswore their

Hippocratic oaths—

waited, pounced and locked her up.

Though she lacked a medical license,

genes linked her hands back to Baubo

—the goddess Demeter’s handy nurse

(that vulvic clown whose gestures brought back spring).

Ancient DNA:

Agamide, Agnodike,

Hygheia, Panacea,

Helen of Troy, Medea, Circe,

the Virgin Mary Panaghia.

ΙΙΙ

Manna Eleni –née Ploumbides—

her maiden-name summoning plumed wings

sprung somewhere back in Asia Minor,

a midwife in stark uniform:

black crinoline,

a pocket watch,

a modest cross of gold.

Always dressed in black,

what was she mourning?

Lost valleys, lakes, mountains?

Captured in old photos, she

looms large above her brood,

(even while seated)

unsmiling,

like that other mother who once sat

blocks away, in what was now

Lowell’s Greek Acre,

a city crammed with thousands of Greeks:

the famous Anna Whistler—also in mourning weeds—

immortalized in her crafty son’s

iconic painting

“Arrangement in Gray and Black.”

James Whistler, Lowell-hater.

His Worthen Street abode

proved unworthy

of a dandy born in Lowell,

not by choice, but only “to be near my mother.”

In elementary Greek school,

during recess we’d unleash our spleen

by throwing rocks against the side

of an abutting dark gray house

(Whistler’s own, now art museum)

sometimes aiming at the homeless woman

cringing on the stoop: Depot Annie,

a black-clad crone who posed for no one.

Manna Eleni’s house of dreams:

a shelter for nine grandkids,

countless cousins, relatives, compatriots,

bishops, piano teachers,

an occasional swindler.

It saw six grandsons leave for war,

Purple Hearts replacing broken hearts.

It aged, it creaked,

it pitched and leaned,

it held four generations in its

cracking wooden beams.

IV

Some months before the house went on the market

by chance I found an old lamp

among the cellar’s vast debris,

a properly Victorian affair

crowned with a stenciled, tasseled silken shade,

covered hopelessly in filth.

The painted base—a Chinese vase—

once cleaned,

revealed a pair of sporting peacocks

highlighted in gold,

quite beautiful and highly Whistleresque,

as if in tribute to the city’s painter

and his famous Peacock Room.

Who chose this opulent lamp, and how it came

to grace the home of Manna Eleni

is anybody’s guess.

A liking for Chinoiserie?

A bargain in a downtown shop?

A hankering after plumes

in a city beauty-starved?

Plumage, bird tails, golden tracery,

Whistler’s infamous designs—

feathers that were all the rage.

Proximities artistic and maternal . . .

Manna Eleni’s house no longer stands.

New owners, careless,

proved most catastrophic.

Embers, burnt beams,

bones that no one could reset,

bannisters down which we slid as kids,

all now black as coal and broken.

Sloping porches wrecked,

a house combustible beyond itself.

We watched it burn in disbelief.

But was it merely wood that fed

that raging stubborn fire?

Speaking through tongues of flame

Eleni took repossession of her house.

With nothing now left standing,

no chance for further waste or loss,

your house, dear Manna Eleni, is gone.

Still, it beckons to us,

immortalized in photographic

shades of black and gray,

like your defiant gaze.

Peter Jeffreys ©2017

Peter Jeffreys is an associate professor of English at Suffolk University in Boston. He holds a PhD from the University of Toronto, an MA from Boston College, and a BA from Hellenic College. His books includeReframing Decadence: C.P. Cavafy's Imaginary Portraits (Cornell University Press, 2015); E.M. Forster-Κ.Π. Καβάφης Αλληλογραφία:Φίλοι σε Eλαφρήν Aπόκλιση (Ikaros Press, 2013); C.P. Cavafy: Selected Prose Works (University of Michigan Press, 2010); The Forster-Cavafy Letters: Friends at a Slight Angle (American University in Cairo Press, 2009); Eastern Questions: Hellenism and Orientalism in the Writings of E.M. Forster and C. P. Cavafy (ELT Press, 2005).