Kostas Vakkas, director. 2015. Dan Georgakas: A Diaspora Rebel. New Star Art Cinema. 53 minutes.

by Peter Bratsis

Dan Georgakas: A Diaspora Rebel (2015) is in many ways a follow-up and partial repetition of director Kostas Vakkas’s previous documentary, Greek American Radicals: The Untold Story (2013). Georgakas featured heavily in the earlier film, which is to be expected, given his importance not only in the field of Greek American labor studies but also because of his contributions to the study of the immigrant Left in the United States. i

A Diaspora Rebel, which features Georgakas as sole commentator, does not so much depart from Vakkas’s previous film but rather takes a somewhat more personal route to make the same point: that there are indeed leftists within the ranks of Greek Americans. As such, the film is a lost opportunity to extend the insights provided by Vakkas’s earlier efforts and to delve much more deeply into not only the complexities of Georgakas’s own Left political engagements, but also the differences between radicalisms in the first and second waves of Greek immigration, as well as the record of participation of Greek Americans in radical movements and currents that are outside the labor movement.

The prevalent notion within Greece is that Greeks in the United State are inherently reflective of the perceived conservative political character of the United States. Of course this is not totally incorrect but belies the long and important history of radicalism among Greeks in the United States, especially within the labor movement. Much of the history of the Greek American left is focused on the first wave of Greek immigration to the United States, from the 1890s through the 1920s. The immigrant experience, the dire and dangerous working conditions that many Greeks faced, the racism that Greeks were subject to in their daily lives, and the strong currents of honor and pride that Greeks brought with them combined to make them among the most rebellious, cohesive, and pro-labor ethnic groups within the United States. Here, Georgakas elaborates on these questions by discussing his own family history and his upbringing in Detroit and by noting key moments in the history of Greek participation in the labor movement, such as Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre of 1914 and the Lawrence textile strike of 1912. Georgakas gives hints of his own political sensibilities when he mentions his fondness for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, an anarcho-socialist labor union), but these moments are easily lost within a more conventional narrative that explores Georgakas’s family origins, their path to Detroit, and their lines of work, as well as, of course, Georgakas’s own experiences growing up in Detroit. Here, for instance, we learn about his rebellious grandfather, the father who valued education and respected the intellectual tradition of the Greeks, and a kind and thoughtful mother who survived the 1922 evacuation of Smyrna. ii We also learn of the ethnic divisions within Detroit during its heyday and the role of Greeks as the ethnic group closest to the Black community, both in terms of urban geography as well as in the similarity of their move from rural traditional communities.

All of the key points and insights about this first wave of Greek immigrants and their radical political tendencies had already been made in Vakkas’s previous documentary. Georgakas, however, belongs to a different generation of diaspora rebels and is of a very different character. He was not a miner or factory worker, nor was he an active participant in the labor movement; he was college educated and placed great emphasis on art and creative works as weapons of rebellion and political struggle.

The second generation of Greek Americans, which includes the children of that first wave as well as the second big wave of Greek immigrants, who came under the provisions of the 1965 Immigration Act until the early 1980s, faced a very different climate and situation. Not only was it the case that Greeks with radical tendencies were largely barred from entering the United States, given the aftermath of the Civil War in Greece and the Cold War sentiments that still dominated here (those with involvement in Left organizations in Greece often went to Australia instead), but the racism and poor working conditions that radicalized Greeks, as well as other Southern and Eastern European immigrants, in the first half of the century had largely waned. As Georgakas explains in the film, the image of Greeks in particular changed dramatically following their heroic resistance to Italian and German invasion and occupation during the war. This combined with the positive impact of films such as Never on Sunday and Zorba the Greek suddenly made Greeks acceptable, sexy even, although certainly not up to WASP levels of respectability. The increased integration within dominant American culture and the increasing affluence and upward mobility of Greeks did, unsurprisingly, result in much more conservative political sensibilities. As Georgakas himself notes in the film, all the major Greek American organizations during the years of the Greek junta (from AHEPA to, of course, the Greek-Orthodox Church) actively supported the government in Greece. Though the anti-junta movement was an eclectic one (academics, artists, journalists, etc.), it certainly was not a mass movement. In this more recent climate, how do we explain Georgakas and his other fellow Greek American radicals? What can explain those strands of Greek American radicalism that were able to survive beyond and outside of the labor movement?

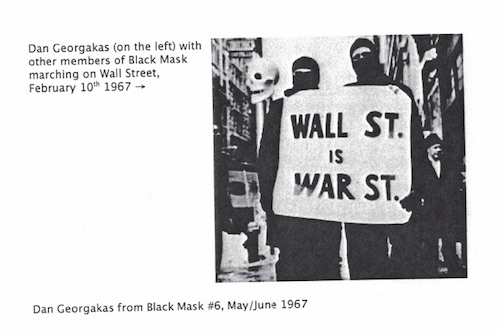

In fact, Georgakas’s own radical political engagements (with the exception of the anti-junta movement) remain untouched in the film. For instance, in 1966, Georgakas founded, together with painter Ben Morea, the New York–based anarchist group Black Mask. The first organization in the United States to refer to itself as an “affinity group,” Black Mask (which also included Osha Neumann, son of Frankfurt School theorist Franz Neumann and stepson of Herbert Marcuse) would eventually, in 1968, transform into the better-known group Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. iii Referring to itself as a “street gang with analysis” and as “armed love,” Black Mask took the world of artistic creation and spectacle as its terrain of struggle. Rather than organizing factories, members wrote poems and literary commentaries, produced visual artworks and musical concerts, and engaged in spectacles (such as one briefly shown in a photo, but not explained, in the film where Georgakas and a fellow member of Black Mask, dressed fully in black with balaclavas, carry a sign down Wall Street with the slogan “Wall Street is War Street”).

Other well-known efforts of Black Mask included dumping garbage from the Lower East Side onto Lincoln Center and shooting bourgeois poet Kenneth Koch with blanks in a mock assassination. Black Mask also collaborated with well-known multimedia artist Aldo Tambellini and other experimental filmmakers. It is on the heels of Georgakas’s activity in Black Mask that he joined the editorial collective of Cineaste Magazine, a key dimension to Georgakas’s work that otherwise appears as disjointed and separate from his other efforts (Georgakas has remained an active member of the Cineaste collective from 1969 until the present).

Although noted in the film, the full importance of Georgakas’s most well-known work, the book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, is underemphasized. It is certainly true that most people who are familiar with Georgakas know him through this work but why should it be that the most complete and well-regarded work on the militant Marxist Black-nationalist organizations Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) and The League of Revolutionary Black Workers would be written by a Greek American? As Georgakas notes, he knew many of the core members of DRUM well from his days as a student at Wayne State and his involvement in radical political circles in Detroit. He was trusted and allowed access to do research for the book but he also understood the sensibilities and goals that DRUM expounded. Here the legacies of growing up in a Greek American family, urban and working class, made possible the important common ground with DRUM. Georgakas makes the key observation in the film that the nonviolent mantra of the more rural and southern Civil Rights movement of Martin Luther King, Jr. did not fit with the urban experience and mindset. In this sense, being from the big cities was as central, if not more, than other variables in understanding Georgakas’s rebelliousness. Indeed, it is certainly true that from Black Mask to DRUM political sensibilities were much more urban and ethnic than anything else.

These entire dimensions of Georgakas’s radicalism—his relation to the labor movement as an ally and scholar rather than as an internal participant; his work as a poet and as an author, editor, and publisher of subversive ideas; and his focus on Detroit and the urban centers of capitalism—all remain ignored or underemphasized by Vakkas. It would appear that from Vakkas’s perspective the only kind of radicalism that Greek Americans may have exhibited fits the narrow stereotype of Greek Americans as workers, courageous members of labor unions, and agents of struggle against capitalist exploitation. The kinds of radical activities in which Georgakas has engaged are altogether different, and it is exactly this radicalism of second-generation Greek Americans that remains opaque. What of the radicalism of Greek American intellectuals and artists, journalists and film directors? It is these kinds of questions that a documentary on Georgakas could and should have addressed.

Notes

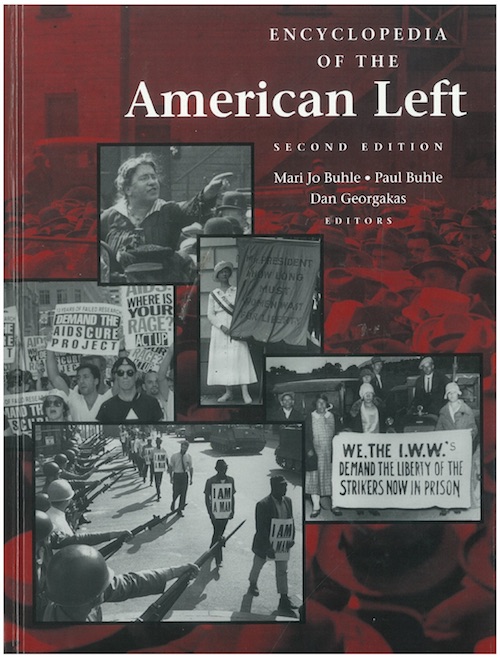

i Key works in this regard include:New Directions in Greek American Studies and The Immigrant Left in the United States.

ii Georgakas emphasizes the point that most Western ships refused to take on the Greek refugees and that his mother was saved by a Japanese freighter. It is interesting to note that the Greek miners in Ludlow were looked down upon by most of the miners who had emigrated from Europe and relegated to one corner of the tent colony, which they shared with the Japanese, who were similarly shunned by the others.

iii Georgakas left the group around this time.

Editor’s Note: Dan Georgakas was active in the anti-junta resistance in New York City. He has shared with Ergon several photographs associated with these activities, mostly protest demonstrations, from his own personal archive (Image gallery).

Georgakas notes: "I founded the Ritsos-Z-Theodorakis Committee in 1967 as a radical adjunct to the regular anti-junta committee. The Committee was later closed to create Demokratia, which remained active until the fall of the junta" (personal communication).

Works Cited

Buhle, Paul, and Dan Georgakas, eds. The Immigrant Left in the United States. SUNY Press, 1996.

Georgakas, Dan, and Charles Moskos, eds. New Directions in Greek American Studies. Pella Publishing Company, 1991.

Georgakas, Dan, and Marvin Surkin. Detroit: I Do Mind Dying: A Study in Urban Revolutio, South End Press, 1975.

Vakkas, Kostas, director, Greek American Radicals: The Untold Story. New Star Art Cinema, 2013.

Peter Bratsis is associate professor of political science at Borough of Manhattan Community College, City University of New York. His publications include the books Everyday Life and the State (Routledge) and Paradigm Lost: State Theory Reconsidered (Minnesota), as well as essays in numerous journals including Social Text,Historical Materialism, Journal of Modern Greek Studies,Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora, andThe Journal of Modern Hellenism. He currently edits the journal Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination and is working on a book, Twenty Years of Boredom: Veganism and the Cultural Logic of Late Liberalism , which examines the rise of veganism and the giving of human names to dogs as symptoms of capitalism.