Interview with Tina Bucuvalas

by Sydney Varajon

Tina Bucuvalas is Curator of Arts & Historical Resources for the City of Tarpon Springs, and previously served as Director/State Folklorist for the State of Florida’s Florida Folklife Program. She is the author, co-author, or editor of five books, the most recent of which is Greek Music in America (forthcoming 2018), and has curated and produced numerous exhibits and events.

Sydney Varajon holds an MA in Folk Studies from Western Kentucky University, and is currently a PhD student in Folklore and English at the Ohio State University. She has worked on various cultural resource documentation projects, and her research explores the intersections of material culture, place studies, and narrative.

I. Occupational and Cultural Backgrounds

SV: Could you describe your role as a folklorist working in Florida, and how you first became interested in cultural work?

TB: I was always interested in culture as a child—probably because my parents grew up in immigrant communities (Chicago and Lowell, Mass.) and my grandparents had emigrated from Greece. Although I grew up in mainstream American communities, I was always aware of negotiating or balancing the history and values of an ethnic family with general American sensibilities of the time. After my family moved to California, I attended schools that had a large Chicano student body, so I became quite familiar with Mexican culture.

In college I studied cultural anthropology, psychology, and religious studies, but didn’t find out about the field of folklore until after I received a B.A. Since I am from California, I received a master’s degree in Folklore and Mythology from UCLA, then went on for a Ph.D. from Indiana University, with minors in cultural anthropology and Latin American studies. My dissertation fieldwork was with Zapotec Indians in Juchitan, Oaxaca, Mexico. Again, being from California, I became aware that by the year 2000, California would be a majority Latino state, so I thought it wise to learn Spanish and specialize in that area. At IU I simultaneously specialized in Greek cultural studies, but I didn’t see the possibility of employment in that field.

I first came to Florida to do contract work for the Florida Folklife Program (part of the Florida Department of State) in 1995. Along with two other fieldworkers, I conducted a folklife survey of the Miami-Dade area, with special emphasis on Latino culture—which at the time was predominantly Cuban. Although I had been dubious about Florida (being from California), it was love at first sight in terms of Florida’s cultural environment. By the next year, the Historical Museum of Southern Florida had created a position for a folklorist and they asked me to return.

I started the folklife program at the Historical Museum, which is still operating today. For the program, I constantly conducted fieldwork in all communities in the region—varying from Cuban and other Latino populations, to Haitian and other West Indian groups, Jewish, Cracker, Greek, Lebanese, and Seminole and Miccosukee Indians, and so forth, as well as communities of those involved in maritime and agricultural occupations. Public folklorists generally have to be able to deal with all traditional cultural phenomena in their area and can rarely specialize in just one group since they are serving the needs of the local citizenry. The documentation was used to preserve and promote culture through museum exhibits, events such as festivals or concerts, workshops, lectures, and essays. At that time I also coauthored, South Florida Folklife, a good deal of which was based on the documentation I did while at the Historical Museum. In Miami I particularly worked with the Cuban community and aspects of Cuban culture, and I made a couple trips to Cuba (1995 and 2011) in order to pursue my own research.

In 1996 I went to work for the Florida Folklife Program (FFP) in Tallahassee, and after a few years became the State Folklorist and Director of the Program. Over the thirteen years that I worked for the FFP, I traveled extensively throughout the state, documenting a wide array of traditional culture. As in Miami, that documentation was put to work in a variety of public events, exhibits, and writing. In addition, we also produced several public radio shows highlighting Florida’s traditional culture, and I administered the Florida Folklife Apprenticeship Program and Florida Folk Heritage Awards. During that period I coauthored Just above the Water: Florida Folk Arts with Kristin Congdon, about visual folklife in Florida. I also received an award to conduct research into public folklife in Greece as a Fulbright scholar. That opportunity, combined with the knowledge and contacts that I acquired, furthered my interest in Greek folklife in Florida.

In 2009 I left the FFP and became the Curator of Arts and Historical Resources for the City of Tarpon Springs. One impetus for the move was that I had started doing serious research into the sponge industry in Florida—much of which was conducted by Greeks in Tarpon Springs. But I had first encountered the industry in Miami, where Cubans harvested and distributed sponges. As I spent more time in Tarpon Springs, I discovered that the City was actually doing little to promote or present Greek culture—though the tourist industry on which the City depended economically was centered around its Greek and maritime culture. Thus when I took the job one of my main goals was to enhance the documentation and presentation of Greek culture. However, the job also deals with other cultural groups in the area—so I also frequently work with Latinos and African Americans. In Tarpon Springs I am involved with historic preservation, such as the successful nomination of the Greektown district to the National Register of Historic Places—the state’s first designated Traditional Cultural Property (i.e., a property nominated on the basis of culture rather than historic building style or the history of famous people). Recently I also nominated Rose Cemetery, an historic African American Cemetery to the National Register. By next year I hope to nominate Cycadia Cemetery—part of which may be the most distinctively Greek cemetery in the United States. Since arriving in Tarpon Springs, I edited two books,The Florida Folklife Reader (2011) and Greek Music in America (forthcoming), and also authored the historic photo book Greeks in Tarpon Springs (2016).

SV: In what ways has your own cultural background influenced your work?

TB: Perhaps the primary way that my cultural background has influenced my work is that by negotiating both Greek America and mainstream America, I developed an early understanding that different cultures possess different social rules and values. In order to work effectively with other cultures, scholars must understand and respect their fundamental assumptions and worldviews—and concomitantly must not consider their own to be the only true way. Truth and beauty exist in every culture, as do institutions, ideas, or behaviors that you may not personally like. My Greek American cultural background also has created a personal preference for lively, Mediterranean-influenced cultures—which for me includes Latin American ones.

II. Greek American and Chicano Culture

SV: What first drew you to work with the Greek American community in Tarpon Springs? What are some of the projects you have worked on in this community?

TB: I have always been generally interested in the Greek American community of Tarpon Springs. Perhaps the first topic that drew me closer was Greek music. While working with the FFP, I worked on several projects that involved Tarpon Springs, during which I became aware of several outstanding musicians in the area. As I mentioned earlier, I also became interested in the sponge industry—which I began studying intensively when I realized that there was a need for more research and for connecting this with the industry in other regions and countries.

When I took the job in Tarpon Springs, my first project was a general survey with a special emphasis on identifying people and trends the music community. I also initiated and have continued workshops in Greek musical instruments. In this regard, my primary intention was to produce a new generation of musicians who could maintain Greek musical traditions. Other projects included Night in the Islands, a panigiri or village-type festival offered monthly from April through October. This is a more traditional format than the ubiquitous festivals developed by the churches. I have also offered concerts of Greek music on various topics in regional or historical music traditions, cooking classes, lectures, and a community photo collection project. Exhibits have included a permanent museum exhibit about the Greek community, Greek Music in America, and photographic exhibits of the Greek community by noted local photographers Eleni Christopoulos-Lekkas and Kostas Lekkas. We are now beginning the production of a short documentary video about the Greek community.

SV: How has your work with the Latino communities been different or similar to your experiences in working with the Greek American community?

TB: While I grew up with Latinos and generally find Latino communities to be kind, generous, and welcoming, I am of course not a Latina but a Greek American. Having outsider status in a community is often positive, since you don’t have to take sides in the inevitable political or social divides that plague every cultural group. The disadvantage of knowing less than an insider is often mitigated by insiders who want to share their culture with you. Sometimes they even confer honorary insider status on you (as have a couple Cuban friends)—possibly because you are more positive about the culture than many insiders who must deal with negative aspects. Folklorists, after all, celebrate culture rather than demean it.

There are both positive and negative aspects to working with your own ethnic group. Certainly an insider perspective is very helpful in terms of access to and interpretation of what takes place in the community. The emotional connection with the traditional culture is more profound, so any successes in preserving or promoting it are more deeply satisfying. The same is true in terms of relations with community members. Nevertheless, there are still degrees of insider and outsider status. For example, in Tarpon Springs there is a deep divide between the older settlers (largely from the islands of Kalymnos, Halki, and Symi) and those who came later and from other regions. So, for instance, just as was true in Miami with Cubans, I once found myself being given honorary Kalymnian status—since my family is from a different region!

Another problem is that, if you are considered Greek and thus an insider, you are often expected to behave or think in ways that align with local standards about what constitutes a “good Greek” –whereas, when working with other groups, you are not necessarily expected to maintain their standards. In many Greek American communities, values are often more conservative than in Greece. But like many Greek Americans, I live in accordance with my personal blend of Greek and American values, which often correlate more closely with those of colleagues in intellectual and artistic fields than general members of the Greek community. This has not been a major problem here because members have been very appreciative of the positive benefits that my work has had for their community.

III. Cultural Activism and the Community

SV: Does your choice regarding mode of presentation differ depending on whether your product is for the specific group documented or for a wider audience?

TB: As a public folklorist, I am usually employed by governmental or semi-governmental agencies. In that capacity, I cannot produce products that are solely intended for one group.

That being said, tensions between the needs of a particular group and the general public sometimes surface in regard to the mode of presentation. For example, the previously mentioned event, Night in the Islands, has been embraced by Greek communities in the Tampa Bay area in large part because of the traditional format that includes social dancing, a combination of old and new, traditional and popular Greek music, and the outside setting and dining common to panigiria. I have an ongoing disagreement with some local colleagues who want to market it more widely in order to bring more tourists. I refuse to do so because with a predominance of outsiders to insiders inhibiting dance circles, Greeks can no longer dance freely nor find a table at which to socialize with family and friends. Thus the event would degenerate from a relatively authentic community-oriented one to the simulation of an ethnic event that would only satisfy outside consumers. So non-Greeks are of course welcome, but I strive to maintain a majority of Greek visitors. Similarly, Greek music lessons are intended to strengthen musical knowledge within the community so that it will survive into the future. During my career as a public folklorist I have rarely encountered a musician who authentically works within an ethnic art form who does not participate socially within the culture—whether or not they were born into the group. Thus, I spend more time and energy recruiting students whom I perceive as likely to develop a serious commitment to the music and participate in the culture.

There are some other tensions implicit in presenting in certain products. For example, when presenting music to Greek audiences, I learned both through observation and advice from musicians that they will not passively listen to Greek music for long periods without dancing—so I always structure musical presentations with opportunities to dance. And as a folklorist I try to present as authentic a product as possible—for example, songs in the original language.

SV: As a folklorist, what are some of the challenges of collaborating with the community in processes of documentation, presentation, and preservation? To what extent are the communities involved, or interested in being involved, in preservation efforts?

TB: It all depends on the community with which you are working and the intensity or duration of your efforts. If you have the luxury, as I do in Tarpon Springs, with living within and as part of the community for an unlimited period of time, your connections expand and deepen so that many will be involved in your efforts over time. Here that has ranged from a community focus group about the history and range of the Greektown district as part of the National Register nomination process; to hundreds of individuals providing personal photographs for a community collection project; to the church helping to host music events or the priests serving as speakers about Orthodoxy at various events; to thousands attending events; and many other ways. On the other hand, on some projects I do most of the work, since I may be the best writer or organizer or because previous experiences with other communities have led me to develop locally innovative ways to present/preserve culture. But in all instances, the community has expressed appreciation of efforts to promote their culture.

However, in the past, especially while a graduate student, I conducted many community surveys for which I had four or five weeks to enter a previously unknown community, acquire knowledge about their culture, and locate individuals or institutions that would cooperate in presentation and promotion of their culture. In those or similar types of projects, efforts simply cannot encompass a very wide range of community participation.

SV: What are the some of the challenges, professional or academic, that a folklorist of Greek America experiences? What are some of the opportunities?

TB: [About the challenges]: Very few academic or public sector jobs have an emphasis on Greek culture because Greeks are such a relatively tiny part of the population (0.4 percent in 2010). In terms of academia, classical Greek culture is given far more attention than more recent culture. While much of this derives from the historical attention paid to ancient Greek in academia, there are other issues. One problem is that wealthy Greek Americans often donate money to universities, museums, and other institutions that provide programs dealing with ancient Greece—undoubtedly with the intent of group glorification through identification with and invocation of the glory that was Greece. Unfortunately, most institutions ignore the history and culture of modern or more recent Greece.

[About the opportunities]: Since there has been relatively little attention to the field of modern Greek studies and Greek American in particular—there’s still a lot to do! There’s just not a lot of monetary support. Greek Americans love to share their culture, so they are happy to cooperate with research and events.

IV. Culture, Identity, and Mobility

SV: Thinking about the immigrant experience, are there examples (from either the Latino or Greek American community) that illustrate how traditions allow people to maintain connection to their home cultures while in a new place?

TB: I think that maintaining a traditional culture generally allows people to maintain the connection with the homeland—even in subsequent generations that have never been there! But the types of culture maintained may vary depending on when the individual or family immigrated. For instance, for one Greek man who has been in Tarpon Springs for only ten years, his most important connection with his home culture are the weekly soccer games that he plays with other relatively recent Greek immigrant men. Whereas, for second, third, and fourth generation Greek Americans whose families came from conservative and remote villages, Greek Orthodoxy or certain food traditions may be the tie that continues to bind them to their ancestral land. Those may not be as important to the recent immigrant, who is generally less religious and more Europeanized. Overall, though, I see it as a natural human reaction to want to maintain a sense of connection with their culture and compatriots because it feels like home.

Editor’s note: For photographs of Tina Bucuvalas in fieldwork settings see "Tina Bucuvalas in Fieldwork Settings" gallery

Credit

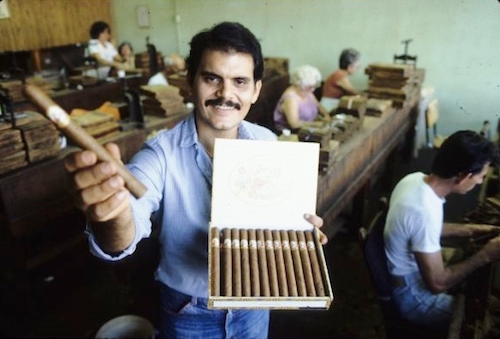

Cuban cigar maker Ernesto Perez-Carrillo. Photo by Michele Edelson.

Haitian vodun paket congo maker Carole Demesmin, Miami, ca. 2000. Photo by Bud Lee. Courtesy of the University of Central Florida.

In all cases where there are no photo credits, either Tina Bucuvalas took the images or the photographer was unknown.