The Castle Gate Mine Disaster Centenary:

A Tribute

If the “Castle Gate” could only speak

I wonder what it would say.

—Joanne Houghton Hyatt1

Photo from the collection of Bill and Albert Fossat.

Utah Historical Quarterly

70.1 (Winter 2002).

It was in the Masonic Cemetery in Trinidad, Colorado, in 2022 that I first encountered the presence of large-scale loss of migrant life. We were visiting with a colleague to pay respects to the grave of Louis Tikas (1886–1914), a labor organizer who was beaten and shot in the back during the infamous massacre in Ludlow—now a ghost town north of Trinidad—during the coal miners’ yearlong strike. Once we identified Tikas’ restored grave and while recovering from the absorbing experience of the proximity to his remains, my attention veered to the adjacent burial sites. We were stunned to face rows of graves, humble in comparison, of buried immigrant bodies whose tombstones revealed untimely deaths. They were of Greek and Japanese men, their surnames and language on the marker revealing their nationality, their deaths linked with industrial mishaps or disasters so common at the time. I had read about Tikas prior to this visit, which was felt as a pilgrimage, and I had seen the photograph of his badly bruised face taken at the morgue. Imprinted in my mind, the image followed me when coming face-to-face with his grave, turning memory into rage, haunting me still. But who were the other individuals buried near him? How did they die and how do we remember them?

A week later, in the ghost town of Castle Gate, we visited yet another harrowing death scape of enormous scale, connected with the massive loss of coal miners. A section in the Castle Gate Cemetery is lined up with hundreds of graves, each marked with a mere rebar cross, with no information other than the date the buried person was killed. The date is March 8, 1924, the day when a series of fiery explosions in the nearby and now-closed Mine No.2 killed all 171 coal miners underground. A plaque at the entrance lists the names of the deceased, the cemetery hosting many of the churned and broken bodies of those victims impossible to identify. The remains of others are buried in the Price Cemetery, which includes a section for the Greek Orthodox miners, Salt Lake City, and elsewhere.

The lives lost in Castle Gate in Eastern Utah are not disconnected from those buried in Trinidad, South Colorado. In fact, both cemeteries are components of a vast network of burial sites that span across New Mexico, Montana, Virginia, Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Oregon, and other landscapes where violent death among laborers was part of the gruesome reality during the nation’s early industrialization. Thousands of lives—a great percentage of migrants—were lost in the mines, railroads, smelters, lumber yards, hydroelectric plants, textile manufacturing facilities, and their burial grounds, a form of industrial deathscapes. This death toll presses for reflection.

On March 8 this year, we observe the centenary of the Castle Gate Mine No.2 disaster, Utah’s second worst in history. Early in the morning of that day, 171 miners were killed while extracting coal. A high proportion were married, 114 in total. The youngest among the victims was 15 years old—child labor was not uncommon at the time—the oldest was 73. One member of the rescue team died after inhaling carbon monoxide. The disaster devastated the families of the dead. One wife of a victim from the island of Crete bowed to despair and died in 1927.

A reflexive commemoration of the Castle Gate centenary calls for recognizing this calamity as a component of a broader historical phenomenon in the early twentieth century. The context is industrial capitalism connecting migrancy with the supreme economic importance of coal as an engine for development. It is about the inexpensive labor force needed to extract vast deposits of minerals, coal, and natural resources and its consequent transportation via rail to the smelters, factories, businesses, construction sites, hospitals, and homes across the nation. The subject is laborers whose toiling bodies, vital in driving economic growth, met violent deaths, a horrific end linked not with mere “accidents” in perilous occupations but the issue of safety in the workplace.

What do we owe to the Castle Gate deaths, but also to thousands of others who perished while laboring under grim conditions in the nation’s industry? If, indeed, memory mediates our relationship with the deceased, how do we remember the victims of industrial disasters? How do we remember dead people about whom there is only a sparse and fragmentary archive? The poem’s lines in the preface—“If the ‘Castle Gate’ could only speak”—recognize the enormity of the ordeal, pointing to the limits of capturing in representation its multifaceted realities in the past.

Industrial workers are individuals largely invisible in history, even though their labor has been a pivotal agent in the nation’s history. But ongoing public “memory work”—often resulting in monumental remembering—keeps the memory of workers killed alive. The question of how we emplace, in history, those untimely lost centers on these mnemonic initiatives. What is the significance of placing their past into our present?2

Castle Gate: Possibilities of Remembering

I began writing about the Castle Gate Mine disaster on January 1, 2024, for the specific purpose of contributing to its centenary commemoration. One motivation sprung from my encounter with their burials, which filled me with a sense of obligation to honor the deceased. Another was my professional responsibility as a researcher who is venturing into migrant labor scholarship and who practices Greek migration studies. My resolve and sense of urgency were enhanced by the knowledge that some ethnic institutions shy away from meaningfully exploring, even recognizing, this past. In this respect, my “act of remembering” intervenes against this marginalization.

In my interest to produce a tribute, I was soon confronted with the immensity of the issues involved. What is it that we do when we speak about the dead? What are the epistemological and ethical dimensions of this kind of work? How do we get to know that past, and why bring it into the present? There is an impressive corpus of deeply reflective scholarship about mourning, modes of memorialization, labor heritage, embodied trauma, emotions in history, and the ethics and politics of remembering. This humbles me, making me underline this memorializing work’s introductory and tentative scope.

The social memory of lives lost in mass destruction involves acts of remembering. In ritual commemorations, it is a moral imperative to remember the proper names of those killed in wars or disasters. The connection of the dead bodies with the name they fundamentally responded to while living offers “‘the most meager memory of a person’—‘meager’ in the sense that it is the minimum required labor of memory, the most basic means of representing the dead in the discourse of the living.”3 Indeed, it represents a moral gesture combating “the anonymity of mass death,” creating “a place [for the departed] in the world of the living.”

The labor of memorializing the names of those killed in Castle Gate has been performed by regional civic organizations, ethnic communities, and other institutions, an activism which has resulted in at least four commemorative monuments: The Plaque listing the names of the dead at the entrance of Castle Gate Cemetery (1987); the Mine Disaster Memorial in Helper, Carbon County (1987); the plaque at the Hellenic Historic Monument at the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Salt Lake City (1988); and the headstone for those Greek immigrants buried in unmarked graves in Price City Cemetery (2005).4 Although varying in design and the specifics of intent, linking these monuments together creates a memory space of official memorialization. By naming the deceased individuals, they restore a central aspect of their identity, a fundamental element of their humanity. In at least one instance, the Hellenic Historic Monument, the narrative of its purpose explicitly invites the descendants of the victims and citizens to undertake a pilgrimage, to pay respect, to lay flowers, to even kneel and cry.5 Acts of remembering call the bodies of the living to engage in honoring the bodies of the dead.

Photo credits: Angeliki Tsiotinou.

Memorialization opens a variety of possibilities regarding the purpose of remembering. This tribute opts to connect the migrant coal miners’ emotions—fear, fury, grievances, aspirations—with the realities shaping their experiences as coal miners at the time—their workplace conditions, the labor struggles in which they participated, and the nativism to which they were subjected. This intertwining of subjective feelings with the realness of the material and ideological conditions that laborers negotiated aims to historicize those individuals untimely lost in the disaster. The sources are published scholarship and online archival records such as historical photographs and newspapers.

Migrant labor history constitutes neither a uniform nor singular, ethnic-specific history. Rather, it involves sedimented histories, multiple histories operating “alongside one another,”6 involving cooperation and solidarities, divisions and conflicts, often along racialized and class fault lines, as well as culturally specific differences in migrant adaptations. This tribute recognizes this dynamic. When it comes to cultural particulars, I gravitate toward Greek immigrant examples due to my greater professional command of this subject.

Deathscapes in Industrial Workplaces

Industrialization connects with dehumanizing death. Writing about it is necessarily macabre, and it might still be troubling, a source of great sorrow, and even unwanted by families today. But I feel it is necessary to communicate the scale of lost lives and a measure of the horror experienced, both by those killed and their families in the aftermath. There can be no genuine commemoration of mine disasters neglecting its ghastly dimensions. The laborers’ encounter with death was horrific and profoundly distressed families and communities, affecting many lives irrevocably. It is an inextricable part of labor history.

Industrial deaths were often sudden and violent. Methane gas and coal dust, the two primary causes of mine explosions, resulted in only a small fraction of the total death toll among coal miners. “Of the 41,746 miners killed while working underground between 1870 and 1912,” journalist Nick Pappas writes, “only 7,502, fewer than one in five, died in accidents resulting from gas explosion, coal-dust blasts, or fires.”

Three times as many (26,480) were crushed by falling coal or rock, often one or two men at a time, while others met their deaths by being struck or run over by mine cars (5,676), electrocution (589), suffocation (216), animals (207), mining machines (85), or other causes (1,874). This would continue throughout the century.7

Laborers were charred, disfigured beyond recognition in mining explosions, buried under collapsed coal—killed or maimed—broken in pieces by a slab of rock, burned by molten ore, killed in accidents or shootings, smothered in pits of coal, drowned in dams, or struck by falling timber. “Women, banned by law from minework—until at least the early 1970s”8—lost lives in the textile industry, among other workplaces. The horrific Triangle Waist Company fire in New York City’s Garment District on March 25, 1911, “claimed the lives of 146 workers, mostly girls and young women.”9

The death count also links with those who languished prematurely because of work-related illnesses—consumption and black lung disease, complications following amputations, arthritis, or withering away due to incapacity. Young bodies were literally swallowed by the ground and the waters of the new land whose resources they were extracting and processing in the service of industrial growth and, in turn, the nation’s economic and military might. We will never know the precise number of those who perished due to the long-term consequences of haphazard work conditions.

But what we do know points to a stark macro pattern. “Starting in 1900, no fewer than one thousand men were killed each year until 1946, when fatalities crept downward to 968.”10 The exact count of bodies destroyed in disasters—defined by the Federal Government “as any incident that resulted in the death of five or more workers”11—illustrates the scale of loss. Two “of the most horrific mine disasters”12 in the United States happened in Utah’s Carbon County, one being the Castle Gate Disaster Mine No.2 in 1924 and the other the Winter Quarters Mine No. 4, on May 1, 1900, claiming the lives of over 200 men. In December 1907, the explosion of Mines No. 6 and 8 in Monongah, West Virginia, killed 362 workers. The two coal mine explosions in Dawson, New Mexico, one on October 22, 1913, and the other on February 8, 1923, took the lives of a total of 383 men. The mine explosion in Hastings, Colorado, on April 27, 1917, killed 121 miners. Mine disasters plagued the global community of miners. The “worst mining disaster ever in the United Kingdom” took place in South Wales on October 14, 1913, killing 439 miners. The “worst mining disaster in world history” occurred in the Liaoning province of China on April 26, 1942, taking the lives of 1,549 people.13

The Archive: Bodies in Motion, Bodies in Containment

Traumatic events wounding families and disturbing communities may resist transmission across generations. Historian James Walsh points to this interruption in connection to the sorrow felt among the Irish immigrants when co-national miners were buried on a mass scale in unmarked graves during the Silver Boom (1877–1890) in Leadville, Colorado. “It was so traumatic,” he notes, “that it was not passed on in oral tradition. Grandparents didn’t pass it down to parents to pass it down to children, because it was so traumatic. The message was always: get an education, move forward,” escape the perils via the route of alternative occupations promising mobility.14 The laborers sought to protect their children and grandchildren’s cognitive and physical health.

George Makris’s account about his father, Vasilios G. Makris, in connection to the 1913 Dawson Coal Mine explosion, illustrates this propensity to silence. Vasilios was a toddler when his father and uncle were killed—two migrants from the island of Karpathos—among the 286 miners lost in the disaster. George recalls “that his father never spoke much about Dawson. When he did, George said he could tell his father felt ‘great sorrow’ over never getting to know his own father. In his later years, he [Vasilios] expressed some regret over never making a trip to New Mexico to visit his father’s grave.”15 Memory held by generations with no direct experience of a disaster share the trauma as “post-memory.”16

On the other hand, Crete-born Charles George Skandale, one of the 26 survivors in the same disaster, “never spoke much about Dawson, though one time,” late in life, “he did share his story with [his granddaughter] that she recounted for a college paper in 1981.”17 One could carry the weight of an eye-witnessed horror in silence until resorting to words when circumstances feel right.

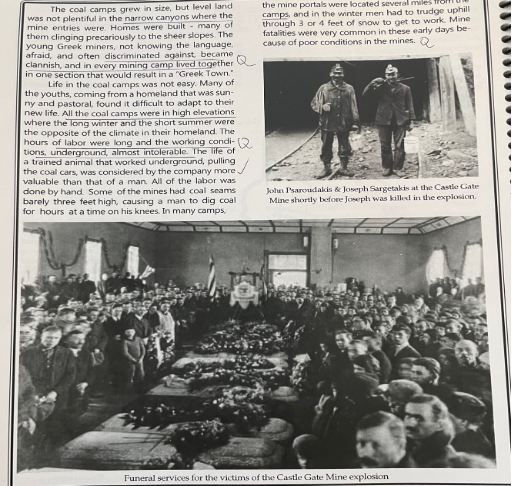

It is not accidental, in this respect, perhaps, that the Centennial Anniversary album of the Assumption Hellenic Orthodox Church (1916–2016) in Price, Utah, the seat of Carbon County to which the site of Castle Gate belongs, and where the great majority of the killed Greek miners are buried, offers minimal narrative about the tragedy. The only reference is two historic photographs.

One captures the “Funeral services for the victims of the Castle Gate Mine explosion,” and the other portrays two miners, “John Psaroudakis & Joseph Sargetakis at the [portal] of the Castle Gate Mine shortly before Joseph was killed in the explosion.”18 The fact that the records of the Parish were burned in 1932 due to intra-community conflict does not contribute to archival memory.19 Involving living descendants, historical memory in these regions could be contested, a subject of subtle navigation.

Migrancy, Coal Industry, Racialization

Unlike Carbon County, the archive about Greek migrants in Castle Gate, a coal mining camp established in 1883 and incorporated as a township in 1914, is sparse. Fragments of information are dispersed in Utah’s newspapers, state and academic archives, the work of regional historians, family lore, genealogy, and community documents. It is a story of dramatic geographic mobility—hopeful and dangerous as many soon discovered: farmers familiar with the demands of the Old World’s agricultural economy emigrating to join the alien (and alienating) challenges associated with U.S. industrial workplaces.

Local history indicates three male migrants entered the town in 1903, their numbers quickly proliferating in that locale and camps across the county due to the vast coal deposits in the region being opened to mining. Workers were also brought by the infamously exploitative labor agent Leonidas Skliris to break the 1903 Carbon County strike of Italian miners. By 1910, the numbers of Greek miners in the region were soaring, numbering 4,039 individuals making up “6.4 percent of the foreign population,” representing the majority workforce along with the Italians in Castle Gate.20 Transatlantic crosses were often illegal, as rural Greeks were entering the U.S. as contract laborers, an unlawful practice in the United States.21

High demand for labor and relatively high wages pulled immigrants toward coal towns and camps, the attraction offsetting the “extreme potential danger” —“coalmining remained the most dangerous jobs at the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”22 At the time of the Castle Gate explosion, the memory of the second Dawson disaster a year earlier, where 120 miners died, was fresh in the region.

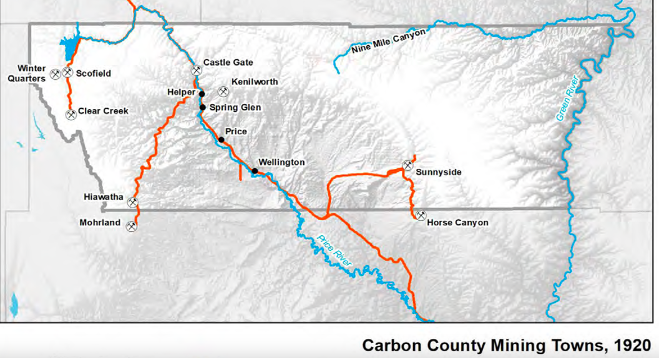

The three mines in Castle Gate were part of a wide network of camps opened by the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad and the railroad’s coal subsidiary, the Utah Fuel Company.

Cast as the Ellis Island of the West, Carbon County was turning into a multi-ethnic region, attracting laborers from as far as Australia, China, and Japan. The 1920 Census lists 1,215 workers from Italy, 83 from Finland, 6 from Australia, 115 from Scotland, and 869 from Greece (primarily from Crete) among more than twenty-three nationalities.23

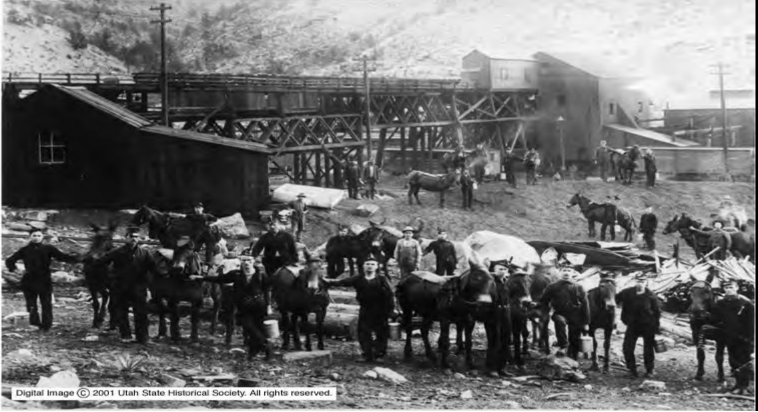

Source: “Castle Gate, Utah-Mining p.4,” Utah State Historical Society,

Classified Photograph Collection, 1920, 2010.

Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society

For the Greeks, entering the coal country of Carbon County involved chain migration—Cretans and Roumeliots sending letters about the abundance of work, inviting relatives and co-villagers. “The young at the turn of the century sat in village squares and in coffeehouses,” historian Helen Papanikolas writes, “listening to priests reading letters from Ameriki and gazing at photographs of former villagers dressed in American finery. Work was everywhere, the letters said, especially on the sidhero dhrames [sic] (‘rail lines’).” Upon arrival in Salt Lake City, information gathered in the coffeehouses—the migrants’ social centers—incentivized a great many to gravitate toward coal mining where wages “were twice as high as on the railroads,” in exchange for high risks. The “loss of a leg or an arm or blindness from mine blasting,” Helen Papanikolas writes, “meant return to Greece and destitute, help to parents and dowries for sisters a lost fantasy.”24 An intact young body meant lingering hope, a traumatized body the collapse of individual and family planning. Workers’ compensation laws were not introduced in Utah until 1917.

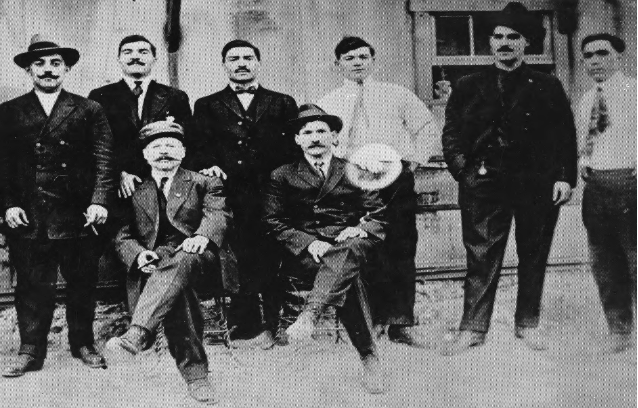

Source: “Greeks in Utah,” Utah State Historical Society, Peoples of Utah

Collection, 1907, 2008.

Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society

It was a highly fluid and mobile labor force consisting of transient workers—those fired after participating in a strike (a common occurrence), those searching for better wages or safer conditions, or those seeking to join a relative—moving across a vast network of coal production and railroad work spanning beyond Utah, across Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, and other states in the Intermountain West.

Some Greeks began settling in the region once picture brides arrived in the 1910s. Women offered companionship and fulfillment of the cultural ideal of marriage and expectations for reproduction. Weddings offered occasions for celebration, adding layers of enjoyment in the spectrum of migrant social life—music and song, the male sociability in the coffeehouse and saloons, a night out in the town, church attendance, family, providing pleasures, joys, and cultural connectivity with the world left behind.

Source: “Greeks in Utah,” Utah Historical Society, People of Utah Photograph

Collection, 1919, 2008.

Used by permission, Utah State Historical Society

There were intermarriages across various immigrant groups, too. Interracial marriage was banned in Utah until its repeal in 1963, and regional racism at the time violently opposed it. Seen as less than White but having “entered the American polity as free White persons,” southeastern European migrants qualified under law to marry American “White” women. According to one list, at least five Greeks were involved in this kind of union.

Coal mining camps and towns were racialized, crisscrossed with various gradations of racial differences and hierarchies. One distinct racial fault line was drawn between migrants from southeastern Europe and those from Japan. In Castle Gate and elsewhere, Japanese migrants were forced into residential segregation. Greeks and Italians were considered “White enough” in this instance to mingle with the town’s population in the community spaces of amusement halls, built by the Utah Fuel Company (UFC) as “a kind of a center for people in the camps.” Internal communication within UFC illustrates an aspect of racialized boundaries in the town. According to a 1917 letter by a UFC official, the rationale for installing ventilation systems in the amusement halls at Sunnyside and Castle Gate was to eliminate “the present practice of Americans moving to other seats in case Greeks or Italians take seats immediately adjoining them. The primary reason for moving usually being that bodily odor from the foreigners is offensive.” But as historian Philip Notarianni notes, “any apparent leniency directed toward the Greeks or Italians was not afforded the Japanese as the same official in various telegrams sought a separate Japanese Hall and “Jap” pool hall for Sunnyside.25

But racialization was shifting, context-specific, and contested. In 1923, the Greeks in Price were viewed as a sexual threat to the “American girls” they employed in their confectionaries and restaurants. Handbills were posted warning that “no foreigners would be allowed to employ American girls in any capacity and that foreigners should not speak to American girls on the street on penalty of severe treatment.” While natives “invaded the Greek restaurant kitchens and ordered the ‘American’ girls home,”26 the local News Advocate and The Sun protested this public policing, condemning the assaults against Greek businessmen—seen as worthy citizens—but also castigating the “undesirables” among the Greeks and lashing out against those resisting “Americanization.” It was at this time, in 1922, when the American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association (AHEPA) was founded to protect business proprietors from nativist intimidation.

The class fault line between the unionized immigrant working class and small-store owners was central in the social dramas of immigrant Whitening and contestations of what constitutes Americanization. While AHEPA—which as an institution embraced and performed the dictates of “pure” Americanism for the interests of the emerging immigrant class of businessmen—was praised for this assimilationism, Greek laborers who joined unions were seen as un-American by the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) though the migrants were embracing the “labor’s version of Americanism,” demanding the right to organize for mutual protection, and “an American standard of living, by which they meant higher wages, shorter working hours, and decent working conditions.”27

Migrant’s Laboring Bodies, Married and Single

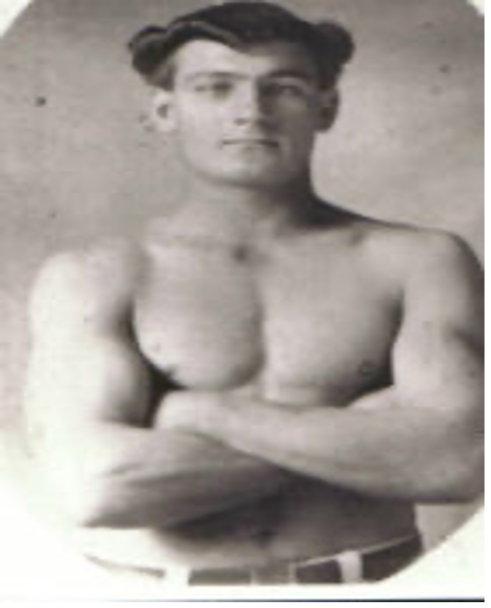

Marital status, as we will see, was a major factor in the coal operators’ labor force management. Physical strength was another determining variable in hiring, given the strenuous demands of the occupation. The story of Jim Dallas (s/b Jim Dellas, b. 1889), who was killed in the Castle Gate disaster, connects migration with a complex history of migrant name changes due to conscious choice, forced Americanization, or simply different versions of spellings. His bodily strength enters the story as a nickname. According to family lore, Dallas was listed as Demetrios Aggelakis-Dellas in his village register, as Delakis in the Price Cemetery, and as Jim Dellas in the Hellenic Historic Monument. Jim settled on the choice of Dellas. “Dellas” was the nickname of Demetrios’ father, which Jim adopted in the United States as his sole surname. Meaning “strong” or “brave,” according to the account, it aptly suited Demetrios, a visibly muscular man. A photograph conveys his physical strength, an attribute that must have been an asset in the demanding coal mining industry.28

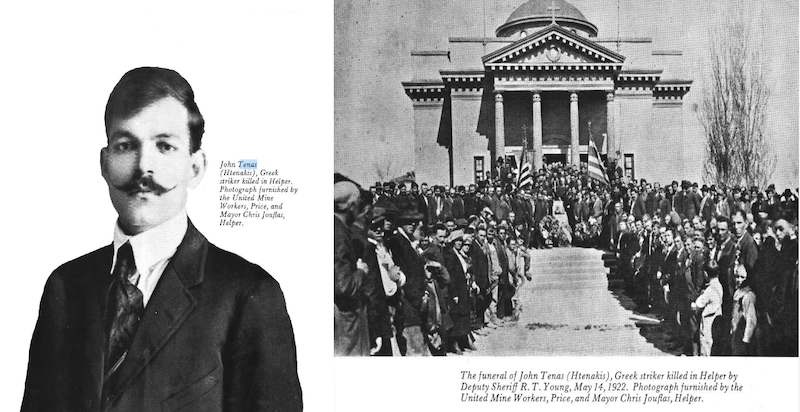

There was also migrants’ involvement in the Labor Movement. In Carbon County, “Italian, Finnish, South Slavic, and Greek miners figured prominently” in the strikes of 1903, 1922, and 1933. Some of those killed in Castle Gate might have participated in the nationwide coal mining strike in 1922, protesting drastic wage reduction and cheating in the coal-weighing machines, which turned violent in Carbon County. On May 14 of that year, a striker from Crete, John Tenas (Htenakis), was killed in a Helper orchard by the local Deputy Sheriff, who was exonerated unjustly from the perspective of the miners and Italian farmers who eye-witnessed the shooting.29 On June 14, in an exchange of fire between strikers and guards, a Deputy Sheriff was killed, resulting in the arrest of fourteen Greeks and one Italian. Some of the trials were still going in March 1924.

Laborers’ fury over the killings and abuses of strikers, exploitation, labor conditions, the operators’ use of strikebreakers, discrimination, and other injustices directed workers, their honor insulted, toward “unionism as a legitimate remedy,” connected with the emergence of class consciousness.30 It was not uncommon for their rage to turn into the use of firearms, to the consternation of labor leaders and miners conscious that such tactics fueled negative publicity and public condemnation.

Forced evictions of miners joining union-organized strikes and the virulent smearing of the striking “foreign element” as anti-American by media controlled by coal operators and sympathizers of the all-powerful KKK were rampant in the post-World War I 100% Americanization and nativist movements. In the case of Castle Gate, single men who participated in the 1922 strike may have been singled out for being fired—they were viewed as agitators—when two weeks before the disaster, the Utah Fuel Company “laid off many unmarried miners and those without dependents during a period of declining coal orders.” This explains the high percentage of the 114 married men being killed, leaving behind 415 widows and orphans.

R. Craig Johnson, a close observer of the mining industry, outlines the corporate calculus in this management of the laboring force:

The married men were given preference for the work as a courtesy to meeting the needs of their families … It was not simply altruistic on the part of the company, however, since the married men were usually both more experienced and had drawn greater advances and had more debts owed to the company store than the single men and generally paid rent to live in company housing.31

Utah’s official historiography incorporates these facts in the state’s educational curricula. A teaching resource for elementary and high school students and the broad public details the predicament of married coal miners. Unlike the single miners residing in privately-owned boarding houses, the married men rented company-owned houses, adding to corporate profits:

These Greek, Yugoslavian, Serbian, and Italian miners [killed in the explosion] left more than 400 widows and children without income, many saddled with debt to the company for rent and food.

Companies provided the housing for their workers and then deducted rent from each paycheck. The cost of goods that a miner or his family bought at the company store was deducted directly from his paycheck. Some miners received their pay as store credit [known as scrip] instead of a paycheck. Miners often went into debt to their employers, which made it impossible for them to quit their jobs.32

Holding a near monopoly of stores in the town, coal operators set up an exploitative economic system that maximized corporate profits while obstructing migrant laborers’ economic and geographical mobility.

Living in Darkness and the Specter of Death

Underground coal mining meant bodies engulfed in dampness and darkness. An investigative report by a rare outside visitor—an Athenian female journalist who obtained a permit to enter the Clear Creek Mine in Utah in the early 1910s—evokes the experience: “Thick darkness encircled us and the water froze my feet. Something was in the underground dampness and cold I had never experienced, something akin to death.”33

Darkness came in various shades in the lives of miners. Laborers exiting the mine exhausted at the end of the shift in the evening encountered a darkness different than the all-consuming one they left behind:

An underground mine is also the domain of the dark. Dark underground is not the same as dark above ground. Underground, the dark is tangible. It is something that the miner feels and breathes. Above ground, even on the darkest of night, there is some light and a feeling of space. Even going to the deepest part of your basement, wrapping yourself in a blanket at night with all lights turned off, the darkness is like day compared to the dark in a mine.34

The theme of darkness permeates miners’ popular culture. A Scottish lullaby evokes it to recognize the value of this labor to produce light, creating an emotionally laden contrast: “There’s darkness doon [down] the mine my darling / Darkness, dust and damp / But we must have oor [our] heat, oor [our] light, / Oor fire and our lamp.”

In the popular song, Dark Black Coal, coal is a vital source for survival and consumes the laborer who wishes to divert his boys away from it: “Dark black coal, take my soul / Owe it to you anyways / Just don’t let my children become the victims / Of the mountains evil ways.” Many men desperate to move out—“wanting to see the sky”—did so the moment they could afford it.35

How did sweethearts and wives feel when boyfriends and husbands set out to enter their dark worlds? How did the miners themselves experience it? The specter of death or potential injury was ever-present. A testimony of the adult daughter of a Greek miner in Utah conveys the pervasive fear blanketing the everydayness of her mother. The sound of the mine rescue whistle, often waking them before dawn, was a terrifying reminder of the nearness of death. She recalls a wife’s life in a never-ending stress:

I remember my father leaving for work in the morning and we would not see him until late in the night and I remember my mother sending us near the tracks, where they knew they would be coming home—and it would be dark and she wanted us to go up there and see if we could see the lights of lamps of men coming out of work, because they always feared that it may something have happened in the mines. So, it was frightening and very, very scary and [my mother] lived in constant fear always.”36

Another source offers a haunting evocation of the wives’ daily experience:

Every spouse, watching the miners headed down the road to the mines, knows and fears that may be the last glimpse seen of that miner. They silently pray that today they will not hear the screaming, pulsating emergency whistle from the mine that summons the rescue crews.37

One descendant of miners conveys the regional state of alert in the immediate aftermath of the Castle Gate explosions: “First whistle, then another, all of the mines around Helper. There were about 28 small and big ones. And the people were running toward the Castle Gate, which was 2 miles from Helper.”38 The thunderous series of explosions announced the scale of the loss. Once it was heard and felt, and while the rescue whistle “continued its scream,” wives, fathers, brothers, sons, daughters, and uncles rushing to the site knew, “the rescue teams would be conducting a recovery, not a rescue.”39 A mine explodes, and families and communities find themselves in shatters.

A “Good Death” in Coal Mining

Death in coal mining communities cannot be thought of apart from culturally specific practices of mourning, expectations regarding funerary rites, and concerns over the well-being of the families left behind. Horrific deaths in industrial zones violated the most earnest wishes shared among various migrant nationalities. If death in their high-risk occupations were to come, it should at least be a “good death.” For the Finns, a good death in these circumstances

meant not dying young, limited pain and suffering, a chance to be mourned and commemorated by family and community (public viewing, funeral), an officiated burial in a marked and preserved space, ensuring that family in Finland was informed of the death, and, if possible, not leaving a bereaved spouse and children in a dire financial position.”40

Greek migrants must have shared this perspective. The bodies of those killed might have been buried in the United States, but it was customary for images of the funeral to find their way to the families of the deceased in Greece. Mourning rituals invariably involved an open casket photograph for the viewing of the body by the family back home. Early in the twentieth century, it was common to have an open casket picture taken, which included the presence of a priest. An archival photograph from the collection of Ernest Benardis41 captures the priest presiding at the center, surrounded by more than 60 migrants, overwhelmingly male, solemnly circling the casket at the front of a church identified as Holy Trinity.

Another photograph features an open casket burial in what appears to be a coal mining camp in the presence of an itinerant priest.

Establishing a visual connection between the dead individuals in the new country and the living in the villages of origin, these photographs not only imprinted the last image of the deceased in the memory of kin at home but also communicated, crucially for the Greek Orthodox, that all the appropriate funerary rites were observed.

For unmarried men killed while employed in industrial jobs, the burials were known as “Death Weddings,” the body dressed “as for marriage”—“white-blossomed wedding crowns on their heads and gold wedding rings on their right hands.” This double rite of passage—marriage in death—symbolically fulfilled a person’s most important purpose in life, partaking in a wedding, a sacramental act in Greek Orthodoxy, and an appropriate ritual burial.42

Mining disasters disrupted traditional funerary rites. The severity of the explosions mutilated the bodies of the miners, making public viewing impossible. Identifying the dead individuals was a harrowing experience for the families, deepening their anguish. In Castle Gate, wives were “permitted in some instances to look at the faces of their loved ones” for the sake of recognition, many becoming “hysterical and have had to be led away from the caskets of husbands and sons.”43

Identifying corpses was often not possible. The “establishment of the identities of the bodies has been only too difficult,” Deseret News reported on March 10, two days after the disaster. “Most of them have been so blown to bits that it is only by dental work, or some thing familiar that only a relative would know that their identities have been fixed. All of the men carried brass identity checks in the pockers [pockets]. In many instances, these have been blown away.”44

Row after row, unmarked graves in the Castle Gate Cemetery host the remains of these individuals. The collective wailing of women lamenting in various tongues must have reverberated across the canyon, multiplying the last farewell, their sorrow directionless with no physical object or site to focus their grief. “It became necessary to send them home,” the Salt Lake Tribune noted, “their unrestrained sorrow was too contagious.”45

Wives’ embodied pain shaped a collective of working-class suffering, the wailing producing a soundscape of anguish released throughout the burial area. A piece in the Albuquerque Morning Journal captures women’s ritual mourning surrounding the 1913 Dawson mine disaster:

…all through the services, which were mercifully brief, could be heard the chant of the Austrian widows, the hysterical cry of Mexican women, the moans of Greek bereaved ones and the sorrowful sobbing of the little group of American women who so suddenly had been bereft of their loved ones.46

In the churchyard, where the bodies went, Greek women “would just beat their chests […] ‘they would beat their legs and they would be all bruised up … and they would pull their hair out.’”47 Inflicting self-pain, destroying parts of her body—hair—brought them closer to the bodies of the beloved, soon to have their humanity decayed in the grave. Lamenting communicated the bridging between the world of living and the world of dead.48

Papanikolas conveys the Castle Gate mourning in connection to the Greek population in the region:

Fifty Greeks were killed. The Greek church in Price was not large enough to hold services for the men and a public hall was used. The widows’ keening of the mirologia, eerie high-pitched dirges recounting extemporaneously the life and hopes of the dead, echoed through Greek Towns. Black-dressed widows, children, and friends followed the caskets to the graveyards. The priest in black robes of mourning chanted final prayers, and the caskets were lowered into rocky excavations.49

In this collective lamenting, we hear echoes of working-class eye-witnessing the violent end of lives consumed in labor for a living. We sense, at least to some degree, the scale of the ordeal.

In Lieu of Conclusion

The Castle Gate Mine Disaster requires a long pause to reflect on the magnitude of its significance to render how to place it in our narrations of the past. Industrial disasters punctuate ethnic idealizations of migrants’ struggle and success as well as national mythologies of equal opportunity and fairness. Not only did thousands of workers laboring to reach the promised American Dream never make it, but they departed with bodies battered by injustices. The disasters call for an investigation of the conditions that failed immigrants and citizens in specific locales and how this knowledge—often suppressed in some circles—matters today. They beckon institutions and communities to move away from grand narratives and toward historiography finely tuned to the social dramas of individual and family lives interrupted and disrupted.

Could the ultimate violence to which migrants were subjected—death in disasters—have been avoided? Was the Castle Gate Mine No.2 explosion preventable if stricter safety practices had been in place? And what would this answer illuminate? The question of culpability demands an answer in tributes commemorating the Castle Gate catastrophe and other industrial tragedies.

In a follow-up tribute to Castle Gate, a work-in-progress, I plan to discuss this all-important question and connect it further with the popular memory and academic historiography of labor relations in early 20th-century Utah. In exploring these linkages, I wish to reflect on the potential of regional historiographies to challenge normative renderings of ethnic historiography. Given the forgetting or marginalization of migrant working-class abuses in ethnic institutions, I will be placing the working-class experience at the center to rethink migrant histories and how this reframing matters in conceptualizing ethnic identity today.

Yiorgos Anagnostou, The Ohio State University

March 1, 2024

Notes

1. Joanne Houghton Hyatt, “The Castle Gate,” March 1982.

2. There has been, of course, a wealth of scholarship on the labor movement and efforts to restore in historical memory labor-related figures and ordinary laborers eluding attention. See the pioneering work of Philip Notarianni, Helen Z. Papanikolas, Zeese Papanikolas, and, more recently, Nick Pappas’ work on the two mine disasters (1913 and 1923) in Dawson, New Mexico, among many others.

3. See Emily Brennan-Moran, Naming the Dead: An Ethics of Memory and Metonymy PhD Dissertation (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2020), 8. Brennan-Moran cites Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory, Harvard University Press, 2002.

4. Mike Correll, “Greek Miners Get their Due 81 Years after their Deaths.” The Salt Lake Tribune, March 6 (2005).

5. See, for example, the narrative about the Hellenic Historic Monument in Salt Lake City. Γιώργος Αγγελίδης [Yiorgos Aggelidis]. 1987. «Επιτέλους! Ένα μνημείο για τα ξεχασμένα θύματα του Καστλ Γκέιτ». Εθνικός Κήρυξ 2 Νοεμβρίου (1987), 6.

6. Alexandra Dellios, Heritage Making and Migrant Subjects in the Deindustrialising Region of the Latrobe Valley (UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 16. Dellios cites Sarah Lloyd and Julie Moore, “Sedimented Histories: Connections, Collaborations and Co-production in Regional History,” History Workshop Journal 80:1 (2015), 242.

7. Nick Pappas, Crosses of Iron: The Tragic Story of Dawson, New Mexico, and Its Twin Mining Disasters. Foreword by Richard Melzer (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2023), 38.

8. Ibid., 69.

9. Ibid., 71.

10. Ibid., 42.

11. Ibid., 37.

12. Craig Johnson R., Afterdamp: The Winter Quarters and Castle Gate Mine Disasters. (Park City, Utah: Free Spirit Publishing, 2022), 8.

13. Nick Pappas, Crosses of Iron, 69.

14. Claire Cleveland, “A Hundred Years After Irish Miners Lived and Died in Leadville, A Colorado Historian Is Bringing Their Stories to Life,” CPR News. June 4 (2021).

15. Nick Pappas, Crosses of Iron, 66. The six Carpathians killed are remembered in the Greek language documentary, The Dawson Mines—100 Years, memorializing the centenary of the disaster (produced by the Pan-Karpathian Foundation, 2014).

16. Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust(New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

17. Nick Pappas, Crosses of Iron,103–104, 199.

18. Assumption Hellenic Orthodox Church, Price, Utah. 1916-2016 Centennial Anniversary.

19. Helen Zeese Papanikolas “The Greeks of Carbon County.” Utah Historical Quarterly XXII (1954), 149fn12, 163.

20. Helen Zeese Papanikolas. “The Exiled Greeks.” In The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, 409–35 (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976), 410fn3.

21. Helen Papanikolas, “Greek Workers in the Intermountain West: The Early Twentieth Century.” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 5 (1979), 195.

22. Richard Melzer, “Foreword” in Nick Pappas Crosses of Iron, xi.

23. Philip Notarianni, “Utah’s Ellis Island: The Difficult ‘Americanization’ of Carbon County.” Utah Historical Quarterly 47.2 (Spring 1979), 181.

24. Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “The Exiled Greeks,” 410, 416.

25. Philip Notarianni, “Utah’s Ellis Island,” 184.

26. Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 38.2 (Spring 1970), 178, 179.

27. James R. Barrett, “Americanization from the Bottom Up: Immigration and the Remaking of the Working Class in the United States, 1880-1930.” The Journal of American History (December 1992), 1009.

28. “Miners Killed in the Castle Gate Mine Explosion.” March 8 (1924) (accessed January 15, 2024. Not available when I checked on February 16, 2024).

29. The following account of the event illustrates how truth was contested in the context of power relations. Miners complained that mine company doctors’ reporting on the causes of miners’ injuries or killings consistently favored the companies and the authorities: “The news burst that John Tenas (Htenakis), a young Greek striker, had been killed in a Helper orchard. Deputy Sheriff R. T. Young, who fired the fatal shot, was treated for a flesh wound. He had narrowly escaped assault by a group of strikers earlier and had been escorted out of town by Sheriff T. F. Kelter. Tenas’s companion had run from the orchard crying out that Tenas was unarmed and had been shot in the back. Italian farmers who had witnessed the shooting testified that Tenas was running away from Young when he was fired upon and that the sheriff then turned the gun on himself and inflicted the flesh wound in his leg. A mine company doctor reported, after examining the body, that Tenas had been shot in the front of his body; a Helper doctor said his examination revealed that Tenas was shot in the back. The Greeks of the county rose up at the killing.” Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “Toil and Rage in a New Land,” 169.

30. Philip Notarianni, “Utah’s Ellis Island,” 184. On the topic of class consciousness among Greek immigrants, see Kostis Karpozilos’ documentary “Greek Radicals: The Untold Story” (2013).

31. Craig Johnson R., Afterdamp, 310, 311.

32. Lisa Barr and Wendy Rex-Atzet, Our Past, Their Present: Teaching Utah with Primary Sources—Diversity in Utah’s Mining Country. (Utah Division of State History 2020), 4, 12.

33. Maria Sarantopoulou Economidou “The Greeks in America as I Saw Them.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 20.1 (1994), 39.

34. Craig Johnson R., Afterdamp, 13.

35. Helen Papanikolas, An Amulet of Greek Earth: Generations of Immigrant Folk Culture. (Athens, OH: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press, 2002), 113.

36. V. Poulos, in the documentary “Utah’s Greek-Americans,” KUED-TV series Many Faces, Many Voices (circa 2000). Overbearing psychological pressure led some women to entrepreneurial initiatives. Deciding “she could not take the stress anymore,” the wife of a Greek coal miner saved the money to buy a Buick as a taxi for her husband. “Utah’s Greek-Americans.”

37. Craig Johnson R., Afterdamp, 13.

38. “Utah’s Greek-Americans,” see note 35.

39. Craig Johnson R., Afterdamp, 6.

40. Samira Saramo, “Capitalism as Death: Loss of Life and the Finnish Migrant Left in the Early Twentieth Century.” Journal of Social History 55.3 (2022), 671.

41. Helen Papanikolas, An Amulet of Greek Earth,”170.

42. Helen Zeese Papanikolas. “The Exiled Greeks,” 416.

43. Salt Lake Tribune, March 11, 1924. Cited in Philip Notarianni F., “Hecatomb at Castle Gate, Utah, March 8, 1924.” Photos from the collection of Bill and Albert Fossat. Utah Historical Quarterly 70.1 (Winter 2002), 71.

44. Deseret News, March 10, 1924. Cited in Philip Notarianni F., “Hecatomb at Castle Gate, Utah, March 8, 1924.” Photos from the collection of Bill and Albert Fossat. Utah Historical Quarterly 70.1 (Winter 2002), 71.

45. Salt Lake Tribune, March 11, 1924. Cited in Philip Notarianni F., “Hecatomb at Castle Gate, Utah, March 8, 1924.” Photos from the collection of Bill and Albert Fossat. Utah Historical Quarterly 70.1 (Winter 2002), 68.

46. Nick Pappas, Crosses of Iron, 56.

47. Ibid., 65.

48. Anna Caraveli-Chaves, “Bridge Between Worlds: The Greek Women’s Lament as Communicative Event.” The Journal of American Folklore 93.368 (April–June 1980), 129.

49. Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “Toil and Rage in a New Land,” 177.

Bibliography

Αγγελίδης, Γιώργος [Yiorgos Aggelidis]. 1987. «Επιτέλους! Ένα μνημείο για τα ξεχασμένα θύματα του Καστλ Γκέιτ». Εθνικός Κήρυξ 2 Νοεμβρίου (1987): 6. [“At Last! A Monument for the Forgotten Victims of Castle Gate,” National Herald, November 2 (1987)].

Assumption Hellenic Orthodox Church, Price, Utah. 1916-2016 Centennial Anniversary.

Barrett, James R. “Americanization from the Bottom Up: Immigration and the Remaking of the Working Class in the United States, 1880-1930.” The Journal of American History (December 1992): 996–1020.

Brennan-Moran, Emily. Naming the Dead: An Ethics of Memory and Metonymy. PhD Dissertation. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2020.

Caraveli-Chaves, Anna. “Bridge Between Worlds: The Greek Women’s Lament as Communicative Event” The Journal of American Folklore 93.368 (April–June 1980): 129–57.

Cleveland, Claire. “A Hundred Years After Irish Miners Lived and Died in Leadville, A Colorado Historian Is Bringing Their Stories to Life,” CPR News. June 4 (2021).

Dellios, Alexandra. Heritage Making and Migrant Subjects in the Deindustrialising Region of the Latrobe Valley. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Gorrell, Mike. “Greek Miners Get their Due 81 Years after their Deaths.” The Salt Lake Tribune, March 6 (2005).

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust.New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Johnson, Craig R. Afterdamp: The Winter Quarters and Castle Gate Mine Disasters. Park City, Utah: Free Spirit Publishing, 2022.

Lisa Barr and Wendy Rex-Atzet. Our Past, Their Present: Teaching Utah with Primary Sources—Diversity in Utah’s Mining Country. Utah Division of State History, 2020, 1–36.

Melzer, Richard. “Foreword” in Crosses of Iron: The Tragic Story of Dawson, New Mexico, and Its Twin Mining Disasters by Nick Pappas, xi–xii. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2023.

Notarianni, Philip. “Utah’s Ellis Island: The Difficult ‘Americanization’ of Carbon County.” Utah Historical Quarterly47.2 (Spring 1979): 178–93.

Notarianni, Philip F. “Hecatomb at Castle Gate, Utah, March 8, 1924.” Photos from the collection of Bill and Albert Fossat. Utah Historical Quarterly 70.1 (Winter 2002): 63–74.

Papanikolas, Helen Zeese. “The Greeks of Carbon County.” Utah Historical Quarterly XXII (1954): 143–64.

Papanikolas Helen Zeese. “Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah.” Utah Historical Quarterly 38.2 (Spring 1970).

–––––––––. “The Exiled Greeks.” In The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, 409–35. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976.

Papanikolas, Helen. “Greek Workers in the Intermountain West: The Early Twentieth Century.” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 5 (1979): 187–215.

–––––––––. An Amulet of Greek Earth: Generations of Immigrant Folk Culture. Athens OH: Swallow Press / Ohio University Press, 2002.

Pappas, Nick. Crosses of Iron: The Tragic Story of Dawson, New Mexico, and Its Twin Mining Disasters . Foreword by Richard Melzer. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2023.

Saramo, Samira. “Capitalism as Death: Loss of Life and the Finnish Migrant Left in the Early Twentieth Century.” Journal of Social History 55.3 (2022): 668–94.

Sarantopoulou Economidou, Maria. “The Greeks in America as I Saw Them.” Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 20.1 (1994): 35–42.

“Utah’s Greek-Americans” (documentary). KUED-TV series Many Faces, Many Voices (circa 2000).