Bob Butero: Moved by the Movement

Bob Butero, the regional director of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), seems calm as he sits in front of me at a long table in the UMWA Southern Colorado Coal Miners Museum in Trinidad, Colorado. Behind him hangs a dark and grim painting by Lindsay Hand of the Ludlow Massacre, the deadliest anti-labor attack in American history that took place in 1914, just 16 miles north. To my left and right I see other paintings by Hand as well as exhibits documenting the miners’ life and struggle for greater justice. But Bob’s composure is deceptive. For he has been fighting all his life, driven by the mission to preserve the past and to struggle for workers’ rights.

In fact, this is what is striking about Bob—his thoughts and actions are less about himself personally than about the movement. Driven by duty rather than by personal happiness, he has been able to go on despite the setbacks labor has suffered since he began working as a coal miner in 1975. When you remain focused on goals greater than you, he believes, you can continue even if you are personally pessimistic.

Bob was twenty-two when he entered his first coal mine. To give a sense of what that felt like, he takes me to the basement of the museum where the curators have reconstructed a mine gallery—dark, claustrophobic, and threatening. It’s hard to imagine how men could enter such an abyss and remain there for eight hours now and sixteen before the labor reforms won by the miners.

Upstairs again Bob explains that he got involved in the Museum—which opened in 2013, adjacent to the Southern Colorado Coal Miners Memorial—exactly to honor and remember the struggles of these miners. Of course, he also has his personal reasons. Having come from a mining family where unionization was key in the betterment of workers, he wants to tell the story from the union’s point of view which, as he says, is often forgotten. The goal of the museum, therefore, is to preserve the history of the miners’ lives, chronicle their struggles, and bring to light the injustices committed against them.

He talks about the meaning of Ludlow, where 13,000 miners had gone on an eight month-long strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. Driven out of the mining compound where they lived with their families, they set up a tent colony by the train depot of Ludlow, a small settlement in a barren landscape about 15 miles north of Trinidad. In the ensuing struggle 75 men, women, and children were killed, including Louis Tikas, the Cretan who helped organize the strike and kept it going. In fact, a lieutenant Karl Linderfelt of the Colorado National Guard broke his rifle butt over Tikas’ head and ordered him killed. Tikas was later discovered shot in the back along with two other workers.

I knew Tikas had died young, a Homeric hero with a short but splendid life who eventually became a symbol of the labor movement. But there is little personal information about Tikas, most of it documented in the wonderful book by Zeese Papanikolas. So I wanted to know Bob’s own perception of Tikas. To fill in the gaps left by history, sometimes you need to rely on the imagination and on empathy. Surely, Bob’s own experience as a miner and as a person who has dedicated his life to preserving the memory of Ludlow could provide insights into Tikas’ mind and motivations.

As Bob begins his own verbal portrait, I study the painting of Tikas by Lindsay Hand. To my left are the few photographs of Tikas in Ludlow, a young man caught in the vicissitudes of history. Handsome with a full shock of hair parted to the left, he seems unaffected by the dangers lurking around him. And I recall that just outside on the square stands the life-size statue of Tikas, next to the monument devoted to miners, and adjacent to a huge metal cage with the sculpture of the miner’s canary.

“So, Bob, what type of person was Tikas?” Obviously, he was brave. Bob thinks he must have been a sharp communicator for he was dealing with men who spoke over 24 different languages. He must have had incredible powers of oratory and persuasion to keep all these men and their families focused on the prize ahead of them, despite the bitter winter, the privations, and the constant gunfire. He was only 28. “He was a unique person,” Bob adds, “an extraordinary man with self-control, who must have had the respect and admiration of those around him.” He was a caring individual and compassionate who obviously must have been “apprehensive” on what Bob refers to as that “infamous day.”

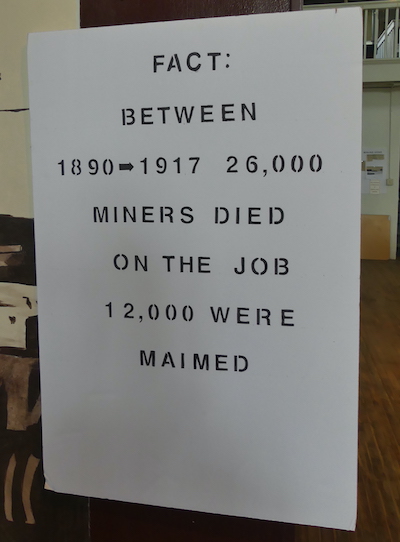

And to die so young. Does it have a meaning? Bob has quick answers because he has been thinking all his life about Tikas and all of the 27,000 miners who perished between 1890 and 1917. As Bob had stated during the unveiling of a statue of Tikas on June 23, 2018, “All workers should remember the sacrifices of martyrs such as Tikas. I used to be a coal miner and I stand on the shoulders of these people. They set the table for addressing health and safety issues in the mines, as well as other benefits such as wage increases that have trickled down to workers in other industries.”

Taking on as his duty to remember, Bob explains how miners have lost many rights since he began work at the age of 22. Back then miners could count on a good wage, a fully-funded pension, and health insurance. And now workers have difficulties in forming and joining unions. And their cause seems forgotten by both the Republican and Democratic parties. People generally don’t care about issues of class and the labor struggle. They are unaware of Ludlow and other tragedies and seem ignorant that what many of us enjoy today like the eight-hour workday was gained by workers’ struggles.

But Bob seems unfazed by the indifference around him. He has just organized the annual UMWA commemoration in Ludlow. And there is the work in the museum, his mission to remind people of what we all have gained through the battle waged by unions. He owes it to Tikas, the other women, men, and children who perished in Ludlow and to the thousands of souls whose life were snuffed out in the bowels of the mines or the harsh landscape around them. It’s not about yourself, we are reminded, but about the movement.

Gregory Jusdanis

teaches

Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at Ohio State. His biography of the

Greek poet C. P. Cavafy, co-written with Peter Jeffreys, will be coming out

with Farrar Straus and Giroux in 2023.

Editor’s Note: “Bob Butero: Moved by the Movement” is part of the series “Profiles of Ludlow.”