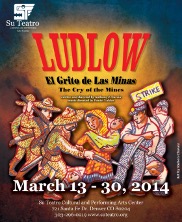

Tony Garcia and the Cry of the Mines

Although the distant peaks glisten with snow, we are sweltering as we make our way through Denver’s Santa Fe district, a Latino neighborhood with shops, restaurants, salons, and its own theater. We are looking for Su Teatro Cultural and Performing Arts Center to meet Tony Garcia, the director, playwright, and producer. Years earlier, Yiorgos Anagnostou heard of his play, “Ludlow: El Grito de las Minas” (Ludlow: The Cry of the Mines) and has been trying for years to get a copy of the script without success. Now through the help of contacts in Southern Colorado, we have finally located Tony and are eager to talk to him and possibly get access to the text.

Credit: Denver Post

Relieved to enter the building, we are startled to break into a group of students rehearsing for a play. One of them quickly leads us to Tony and Associate Director, Tanya Mote. As we move through the building, we can tell from the quality of the furnishing that this is a self-funded enterprise, brought together by those who love culture and specifically the promotion of Latino theater in Colorado.

We explain to Tony that we have just arrived from Ludlow, where we attended the annual commemoration of the Ludlow Massacre, and Pueblo where we saw the oldest Greek Orthodox church in the Intermountain West. His face lights up at the mention of Pueblo for his family stems from that area. A soft-spoken man in his late 60’s, Tony is driven by a sense of political and artistic purpose. As he explains, he has been involved in the arts and political activism all his life. A man on the move, he has written and produced over 35 plays.

Before getting to his work on Ludlow, we want a history of the Cultural Arts Complex itself. How did the Latino community get its own Center, one of the largest such institutions in the country? We learn that Su Teatro emerged out of the Chicano Civil Rights movement in the late 1960s. Specifically, in 1972 students from the University of Colorado (Denver) organized a nomadic theater troupe by doing performances in parks, rallies, demonstrations, and strikes. When Tony assumed the directorship in 1989, the troupe began to produce full-length plays at rented spaces.

With investment from the community Su Teatro finally purchased that year the Historic Ilyria School Building in Northeast Denver to become El Centro Su Teatro, a multidisciplinary cultural arts center. Since then Su Teatro has produced full theatrical seasons, making it one of the oldest ongoing theaters in Denver. In 2010 it moved to its current spot on Santa Fe Drive where we are meeting. Tony proudly says they will pay off their mortgage through small donations they have received from the community.

Having heard about Tony’s and Su Teatro’s involvement with labor issues, it becomes clearer to understand that Ludlow would feature so prominently in the group’s repertory. Tony recalls that the idea for “Ludlow: El Grito de las Minas” was sparked by two events: In 1979 workers in Golden, Colorado organized a strike against Coors which the company tried to break. By coincidence that very year Tony heard from his sister about the events in Ludlow and he tried to make a connection between the two strikes, in 1914 and 1979. Originally, he thought the strike only involved European workers like Greeks and Italians. But upon reading The Great Coalfield War (1972) by the democratic activist and presidential candidate, George McGovern, he discovered that the strike had been multiracial, involving Mexican as well as African American laborers. After much research, he decided to write a play to recognize this racial component that had not been sufficiently recognized until then. At the same time, he also wanted to bring attention to the central role played by women in the strike, another aspect that had not been treated successfully in the past.

The play is primarily in English though the chorus, composed of miners, sings in Spanish. It begins with a song that introduces the historical events, much like the Chorus in a Greek tragedy: “Esta canción triste/ viene de los niños.” (This sad song emerges from the children.) Set in two acts, it was first produced in 1991 and then in a slightly revised version in 2014, the 100th anniversary of Ludlow. Tony reports that members of the Greek community attended this performance, including the Metropolitan of Denver, Isaiah. The play was also performed on site in Ludlow.

Like any artist writing about real events, Tony faced the challenge of how to represent historical figures. Ultimately, he decided that he would be able to imagine these events more freely in his mind and do more justice to them if he created completely imaginary characters. So, instead of writing about Mother Jones or John D. Rockefeller Jr., he opted to tell the story of the fictitious Sara Martinez, whose husband, Enrique dies in a mine collapse in New Mexico and who subsequently loses her small ranch in Northern New Mexico, and moves with her two sons to Southern Colorado, where the boys find work in the mines of Ludlow and become involved in the strike. Through Sara and Martinez, the play puts the focus on the role of Chicanos in the struggle over Ludlow.

In another twist to the historical record, the play looks at the consequences of the strike for the Martinez family by introducing the character of Amelia Martinez-Thompson. Amelia returns to her maternal house in Trinidad to discover that her grandmother (Sara) had been romantically involved with an African American who was killed by Amelia’s father, Jesús, and Sara’s son. The play then switches between the past, set in Ludlow, and the present, set in Trinidad, both places being 15 miles apart but worlds away in the mind of Amelia. This is why, when Amelia arrives at the house in Trinidad, she quickly wants to settle her father’s estate and leave, indifferent to the horror of Ludlow and her own family’s role in the strike. But, as she reluctantly goes over some family papers, she confronts both, that is, the “cry of the mines” as well as the racism in her own family.

In writing the play Tony explains that he sought to highlight the place of women in the strike as most of those killed in the massacre were women and children. Although the lead character, Sara, is Latina (unconsciously based on his mother), he also wanted to bring attention to the internationalism of the strike and also the racism within the communities of Ludlow. The Martinez family can’t accept that Sara becomes involved with an African American. This racial dimension humanizes the strike and makes it relatable to audiences. Tony, after all, needed a personal story. He was writing a play rather than compiling history. As Aristotle says, while history tells us how things actually happened, poetry imagines how they might have happened. That is the difference between a real occurrence and its imaginative recasting as a play.

When I ask Tony about the connection between art and history, he responds that he has always been interested in the tension between drama and trauma and the way theater can enact historical trauma for contemporary audiences. Considering himself Brechtian, he wants to intervene in contemporary political discussions with his theatrical productions. One of the values of theater, he says, is that it involves the senses in the way that the historical narrative cannot. The opening scene and the song convey “a tribal feeling and an indigenous element.” The opening song has a “narrative voice of a Greek chorus.” The play ends with women stomping their feet on the stage, representing in his mind the women’s demonstration in Trinidad against the imprisonment of Mother Jones and the violence of the police and the militia. At the end of the second production, all the names of the individuals who died were projected on the screen. These multisensory aspects of the play, he says, can’t be duplicated in a written narrative. Nonetheless, performing the play outside on the actual site of the massacre, also produced a moment that could not be duplicated, “as the play ended, the final stomping of the women was augmented, by the acknowledging whistle of a passing coal train.”

Ultimately Tony sees himself as a teacher and believes in the “didactic potential of theater.” After all, when we entered Su Teatro, we had broken into a class rehearsal. From his student days, he has sought an alliance of art and labor, theater and justice. In Southern Colorado, he says, places have been named and recognized as tragedy. Ludlow remind us that “sorrow permeates the landscape.”

Gregory Jusdanis

November 2022

Gregory Jusdanis teaches Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at Ohio State. His biography of the Greek poet C. P. Cavafy, co-written with Peter Jeffreys, will be coming out with Farrar Straus and Giroux in 2023.

Editor’s Note: “Tony Garcia and the Cry of the Mines” is part of the series “Profiles of Ludlow.”