“For you, Louis.” Zeese Papanikolas Writes Louis Tikas

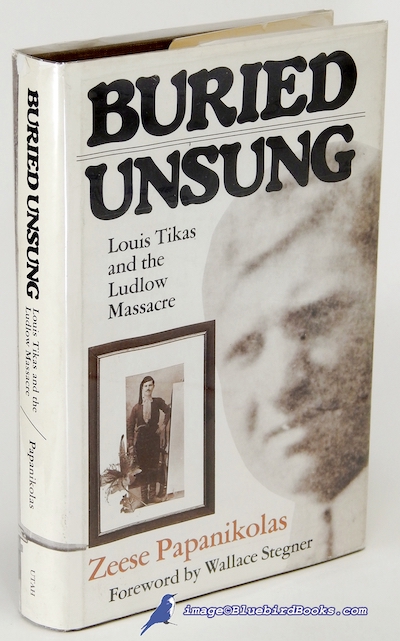

“For you, Louis,” reads the dedication in Zeese Papanikolas’s Buried Unsung: Louis Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre (1982), in recognition of labor organizer Louis Tikas (1886–1914), the subject of the book. An expression of giving, an offering of a gift, the informal acknowledgement conveys closeness between the author—a third-generation Greek American—and Tikas—an early twentieth-century Cretan immigrant: two individuals, strangers to each other, removed by generation and historical circumstance.

“For you, Louis.” One thing is clear, upon reading the book, Papanikolas earned the license for this expression of social intimacy. He achieved it via a pioneering undertaking in the 1970s, when he set out to reconstruct the life of an immigrant little known outside the U.S. labor movement. The name was certainly memorialized in 1918 in the granite monument erected by the United Mine Workers of America at Ludlow—the site where a coal miner’s strike was violently put to an end four years earlier and in which Tikas, along with two other union men, was murdered. “Louis Tikas” is inscribed on the top of the list naming the union men killed and the women and children who died in the clash. But beyond his affiliation with the Union, who was this figure, this newcomer to the country, as a thinking and feeling person? What were his pre-American beginnings—the place of his birth, his baptismal name behind its Americanized rendering? Outside his memorialization as a martyr, Tikas was an elusive shadow in the archive, as Papanikolas notes, a near ghost.

Coming across the name “Louis, the Greek” for the first time in a pamphlet at a library basement while researching a novel, Papanikolas was intrigued and embarked on a quest for historical reconstruction—a daunting task given the meager archive. It required the aspiring novelist to reinvent himself as an oral historian, researcher of immigrant history, and historian of the American Labor Movement. A product of painstaking research and imagination, an account interlacing fact and fiction, the book turned a shadow into a biography, partial and fragmentary, at times imaginative, yet nevertheless a recovery from the “dark hollow of his absence from history” (53).

One realizes the magnitude of the significance of this restoration when one visits his grave, now restored and amply photographed, in Trinidad, Colorado. This is what we did—my colleague Gregory Jusdanis and I—in the summer of 2022. Once we recovered from the absorbing experience of our proximity to his grave, our attention veered to our right only to face more graves, humble in comparison, of immigrant men whose grave markers revealed untimely deaths. They were men who, in their overwhelming majority, met their deaths at work in mine-related disasters so common in that era.

This haunting presence is a regular feature in the deathscapes connected with the history of the mining industry in Colorado, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Virginia, and elsewhere. Many were killed in gun battles during labor tensions, strikes, or altercations. The majority encountered death in mine explosions, many burned beyond recognition, buried in unmarked graves. What we viscerally witnessed that day was the extent of lives violently terminated, markers of individuals with no story attached to their names. Persons ultimately relegated outside history.

In contrast, thanks to Papanikolas, the well-maintained grave of Tikas was conjuring up a story. It was not staring back at us in silence. The research gave back Louis his Greek name: Elias Anastasios Spantidakis. It identified his ancestral village: Loutra. It brought focus to his declaration of intention for citizenship in 1910, imprinting his wish to move from a Greek immigrant to an American citizen, a major passage in identity. The story traces fragments of his American journey, from his coffeehouse in 1746 Market Street, in Denver, to the northern coal mines of Colorado, his involvement with the labor movement, and eventually his activism in Ludlow. The few available archival photographs featuring his figure were brought to the center of public attention, restoring a measure of his humanity.

But in placing Tikas in his historical context, Papanikolas makes available a meaningful angle to see those buried next to him differently. Buried Unsung excavated the story of the immigrant working class, including the Greeks, in their grappling with the exploitative greed of laissez-faire industrial capitalism. The loss of their lives in the workplace was not contingent but the inevitable outcome of a socioeconomic structure which exploited and even dehumanized them. In this respect, the importance of his work extends beyond restoring an individual to history. Naming the forces Tikas fought and the conditions he sought to change, the book recognizes the causes responsible for the untimely death of “men without biographies” (7) whose graves we were shockingly contemplating. If we were in no position to know their individual stories, at least we could recognize their collective plight and the circumstances leading to their killing. We could place them, to some extent, in history too.

The question of what we owe to these dead, unjustly perished, has preoccupied me since that encounter. This kind of loss presses for reflection. Buried Unsung helps me begin formulating an answer. Knowing the circumstances of their demise rescues these individuals from those who sanitize national history. It produces historical memory to keep disrupting the defining of the immigrant experience as one of struggle and success. The victims of capitalist excess—disregarding workplace safety—toiled but were unfairly crushed. Isn’t it our obligation to keep their memory alive in labor politics?

In fact, Buried Unsung proposes an alternative vision of ethnic success, one countering the exhausted yet much-celebrated template of socioeconomic mobility as the apex of fulfillment. Besides its historical and broad cultural value, the book also served the author personally. In an autobiographical thread, Papanikolas is explicit about the personal stakes connected with the project: “How do you write about a ghost?” he asks. “No doubt the thing I was searching for was really a fragment of myself” (3).

In the politicized radicalism and the emerging call for reclaiming ethnic roots in the 1970s, Papanikolas immersed himself in a project of restoring a “dead radical” to life but also his immigrant past. This dual search directed him toward investigating labor history, his quest offering an antidote to Americanization and its middle-class comforts. Far from furnishing self-fulfillment, success led to lame complacency, he laments. Reclaiming the past thus opened a route to reinventing ethnic identity for this third-generation Greek American. Pursuing a fragment of his past, he ended up crafting an authorial self who collected fragments to assemble a collective history, to produce social memory. The Americanized “ethnic” self is realized in actively pursuing historical learning. To recall poet George Economou’s “All-American,” “The Unexamined Ethnic Life / Is Not Worth Living.”

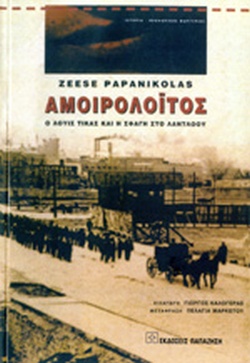

Books acquire a new life via their reception. Buried Unsung does not merely serve as an essential reference point for scholars, journalists, and documentary makers. It keeps inspiring poets, novelists, songwriters, and playwrights adding new layers of meaning to Ludlow and its significance. Restoring one protagonist to life in the drama of Ludlow, it animates renderings of the story across cultural and linguistic boundaries in the arts, turning Tikas into the subject of song, play, opera, and poetry in several languages, including English, Greek, and Spanish.

This is to say that Buried Unsung is a generative book. Zeese Papanikolas brought us closer to how we know Tikas. The result of understanding this archival shadow is inevitably the product of hard historical labor and the work of imagination. The impossibility of a definitive closure and the inability to authoritatively resolve his past spark the creative imagination to keep reinventing Tikas as a source of inspiration and action against class exploitation.

Buried Unsung has elevated Tikas’s cultural presence by motivating us to rethink this figure and bring him closer to different publics. By doing this, we, too, earn the right to honor Tikas with the succinct, full starkness of “For you, Louis.”

Yiorgos Anagnostou

March 5, 2023

Yiorgos Anagnostou teaches in the Modern Greek Program at the Ohio State University.