“Greek Melbourne” Calling! New Cartographies of Diasporic Belonging

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

Publishing a talk, a note: Being attentive to issues of cultural representation means to also subject one’s own representation of a faraway diaspora to public reflection. It requires, I believe, an ethos of openness, which makes me share the talk “Greek Melbourne,” I gave in the New York area on two occasions in March 2024.1 The primary purpose of engaging audiences from one regional diaspora (Greek New York) about another (Greek Melbourne) was this: to bring attention to an increasingly visible diasporic imaginary and practice in Greek Australia, namely the discourse of a diaspora as a cultural center, in counter-distinction to the ideology of Greece as the “diaspora’s” metropolitan center. Two interrelated questions organized my paper: (a) how is this centering of a diaspora expressed? and (b) how is the claim to centeredness validated? The angle of my analysis therefore zooms largely on Greek-Melbournian self-representations.

I analyze a few of those in some depth (a photography and public history project, a sculpture, a mural, a play) while identifying and shortly commenting on others, in the interest of introducing a diasporic modality that would be of interest, I thought, to Greek New York and beyond. To reiterate, this is a consciously selective charting of Greek Melbourne to foreground questions about its claim of diasporic centeredness. This angle of focus, of course, places alternative self-representations outside its frame.

Abstract: Being diasporic animates multiple affiliations. It involves connections with immigrant history, the historical homeland, the new home, as well as other diasporas. Diasporas orient themselves in space and time in relation to the elsewhere and the here, the then and the now. Within this spatial and temporal terrain, they engage with their various pasts, (re)configure the present, and project visions for the future. In this talk I explore how Greek Melbourne places its cultural identifications in relation to the cultural and political fabric of its city as well as Greece and Australia. I draw examples from Greek Australian poetry, murals, photography, critical commentary as well as cultural and political activism. How does Greek Melbourne chart its diasporic belonging? What claims does it make about itself? And what issues does all this raise for Greek diasporic production in global cities such as New York City?

My talk, as the title indicates, connects an Australian city—Melbourne—with Greek identity. It claims that this Australian-Greek connection offers something new, a cultural geography which is worthy our attention. It invites us to think of diaspora in terms of cartography.

Cartography refers to the making of maps. In the humanities, this involves cultural mapping, the identification of people’s “tangible and intangible assets within local landscapes.” The tangible assets include statues, paintings, and archives, among others. The intangible assets involve narratives of identity, music, and literature.

I will begin my cultural mapping of Greek Melbourne from a broad perspective, that of a transoceanic crossing, namely the poetic evocation of a Greek emigration journey toward Australia.

Below is an extract from a poem entitled “The Place” (Ο Τόπος) by Antigone Kefala (1931–2022), a highly respected Australian poet whom we lost recently.

We travelled in old ships

with small decaying hearts

rode on the giant beast

uncertain

remembered other voyages

and the black depths

each day we feasted on the past

friends watching over

the furniture of generations

dolphins no longer followed us

we were in alien waters.

Migration, a trajectory of movement across space, is starkly charted here as a process of distancing oneself from a familiar place—a home. The migrant self is witnessing its gradual removal from the social networks in which it was embedded at home—experiencing a rupture. It is those who are left behind that will now be guarding ancestral continuities—it will be the “friends watching over the furniture of generations.”

Migration also involves reorientation in time. What was the migrants’ presence at home is no longer; it has become the past. Kefala’s poem underlines the all-consuming memory of home—“each day we feasted on the past”—as the migrant experiences the transition away from the familiar. The cartography of migration involves a physical relocation and emotional displacement from a familiar place to a foreign environment.

The poem sketches an initial affective and cognitive cartography of the migrant subject becoming a diasporic subject. The movement across space and along time is crisscrossed with feelings and relations between the here and there, the then and now. The product of movement across space—in its original meaning diaspora refers to the scattering of a population—diaspora conventionally underlines the condition of being at a distance from what was home, and all the social and inner processes which are activated to cultivate relations with the elsewhere of that home.

But as the migrants enter alien waters, yet another process of diasporic becoming is about to commence, as the incoming people are to encounter the power of the host society and its people, which they negotiate, a process which shapes their lives at the intersection of at least two languages and cultures.

The closing of the poem raises the question of what comes next: What futures lie ahead? What kinds of lives (and institutions) will the migrants build? And, to add another layer of complexity, how will the next generation place itself in connection to the spatial dynamic of here and elsewhere and the temporal tension between the past of the historical homeland, the past of the immigrant parents, and the diasporic present?

The poem “Equilibrium” (Ισορροπία) provides an answer. It is written by Irini Pappas, a native-Melbourne actress, poet, and prose writer. It voices a perspective by and about the second generation.

I am the yield of alien soil.

Born here, in Australia,

I’ve learnt all I know of Greece

from others’ lips.

What do you want from me?

Why do you seek, insistently,

to classify me?

It’s time you understood

that I have not just one

but two allegiances.

Neither to one am I pledged totally

nor fully to the other.

My life is rich,

richer than yours twice over

because I’ve found my niche in both.

No-one can deny me

this gift, the ability to live

within the one society

and the other

comfortably.

We, who were born here

are quite another,

quite a separate race [tribe],

and we fit into no-one’s pattern

but our own.

“Equilibrium” asserts a bicultural identity. The poetic persona defiantly resists any demands that impose a single identity on her person. Her voice rejects the authority of national categories as too narrow to accommodate her diasporic subjectivity. In the verses, identity is for the next generation to negotiate on its own terms, engage with two cultures and carve a process of becoming not subjected to imposed categories. One can speak of a creative (and not always easy) process of making something new, that is engage with a poetics of identity.

The poem’s impatient, one might say exasperated dismissal of imposed categories anticipates this phrasing from the internationally renowned Greek Melbournian writer Christos Tsiolkas: “It’s not that I can’t decide [between being Greek or Australian]; I don’t like definitions.”

Diasporic identity in this poetic rendering recognizes the multiplicity and the contingency of identifications. In fact, their instability and fault lines. This is expressed in everyday language in Greek America, too—we routinely hear next-generation Greek Americans registering feelings of double otherness, “They call us Americans in Greece and Greeks in America.” Or “In Greece, I feel American, and in America, I feel Greek.” It is not always straightforward to inhabit a hyphenated identity. National categories cannot possibly accommodate its multifaceted textures.

But let us notice yet another layer in the poem: It extends the scope of diasporic identity beyond the level of the individual. Its last stanza clearly shifts the point of view from the personal “I” to the collective “We.” It speaks about the “tribe”—the descent group.

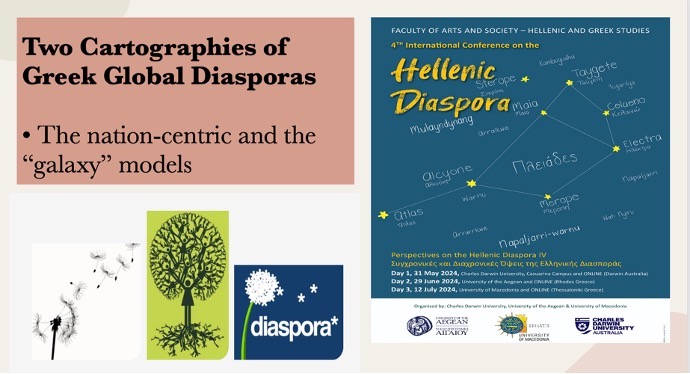

The poem centers attention on the diasporic group as a distinct cultural entity, and in doing so it interferes with conventional cartographies of diaspora. A diaspora is commonly thought, as I mentioned, solely in connection to a people’ scattering from a historical homeland and the links that individuals and institutions cultivate with that ancestral place.

Indeed, but this relation is only one facet of a broader constellation. Diasporas involve multiple affiliations—not only connections with the historical homeland but linkages with the immigrant past, ties with its local institutions as well as the cultures in the new home. Diaspora cartographies involve complex constellations of affiliations involving cross-cultural fertilizations and the ensuing transformations.

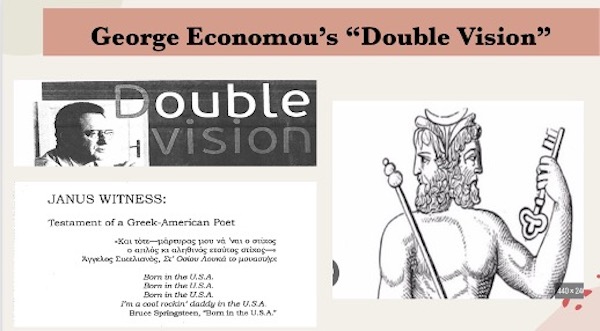

Greek American poet George Economou evokes the image of the two-faced Janus, the god of “beginnings and transitions,” to convey the diasporic position of simultaneously looking to the past and the future, the here and elsewhere. He calls this mode of looking “double vision.” But where does a diaspora person stand for this multiple looking? From what position does she speak? Is it from the vantage point of national belonging, or somewhere else? The poem Equilibrium situates the speaking persona as a bicultural subject resisting national taxonomies, placing its diasporic position at the center.

In this configuration, a diaspora stands neither as an extension of what is called the metropolitan center nor its periphery. It is one center of Hellenism, among others. In this view, the visual metaphor of Hellenism is not arboreal—the scattering of leaves from the national tree, but instead could be visualized as a galaxy of Hellenisms, animated via multiple interconnections. In proposing this decentering of Hellenism, the poem contributes to a new cartography of diasporic belonging.

The poem is not alone in positing a diaspora as a center of Hellenism. It is part of a broader feeling often finding its way in public discourse, including the Greek media. See, for example in the screen below, a statement published in the Kathimerini:

Shared in sectors of Greek Melbourne, this statement and sentiment calls for the cultural mapping of this diaspora as metropolis. How is this centering expressed? How is this claim of centeredness validated?2

Greek Melbourne as a Center of Hellenism: A Cultural Mapping

In Autumn 2023, I spent 45 days in Melbourne, Australia, as a Fellow at the University of Melbourne.3 Soon, I was embraced by the city’s Greek community as a guest and offered plenty of opportunities for conversation and the presentation of ideas. The population of the παροικία is approximately 180,000 people and has the largest Greek-speaking population outside Greece. The post-1950s immigrant generation is aging and leaving us, but the second generation still nurtures living memories of the migrant experience.

The Greek Orthodox Community of Melbourne and Victoria (GOCMV) has its home at a skyscraper in downtown Melbourne, constructed on the site of its original immigrant building. It maintains a network of Greek language schools, including a private bilingual school and several afternoon schools. The Community recently supported research on its archives for the writing of its history. There is still a high percentage of bilingual speakers among the second generation—Greek was the primary language used during my meeting with the GOCMV. I was asked to use Greek language to deliver my talk and radio interviews.

There are hundreds of regional, philanthropic, and welfare social organizations, some going strong, others semi-active. Still in operation is the Democritus Workers League, founded in 1935. There is a literary society and at least two theater troupes. The poetry landscape is robust. There are several Greek radio programs, part of Australian’s multicultural media landscape. The community organizes the popular Antipodes Greek Festival downtown. All-in-all there has been considerable cultural labor toward self-understanding and self-representation (in public talks, university classrooms, bookstores, the media), though several facets of the παροικία remain under-researched or not explored at all.

Amidst this terrain, the idea of Greek Melbourne as a center of Hellenism (in a global universe of Hellenisms) carries considerable weight in sectors of the community’s public discourse, expressed in commentary, newspapers, talks, and social media. This centering of Greek Melbourne certainly relates with the distancing from and alienation with Greece’s approaches toward the diaspora. According to one educational leader, “Greece may not have a true understanding of the different diasporas,” its attitude is paternalistic: “Maybe Greece and the Greek governments perceive themselves as paternal figures to guide us, the children who have left.” The relationship is seen as far from being one between equals.4

This paternalistic lack of respect is a source of exasperation for some diaspora public figures. A few but vital and vocal voices, circulating both in the Greek Australian as well as Greek media, contribute to a critical public sphere. They may protest the authoritarian policies of the Council of Hellenes Abroad regarding the social organization of the diaspora (see the image below) or, more recently, critique Greece’s 2024 strategic plan for the diaspora.

While cultural exchanges with Greece are sought and appreciated, major energies are directed toward empowering local cultural practitioners and institutions.

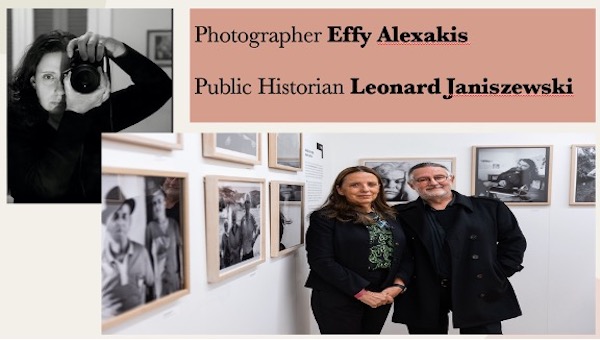

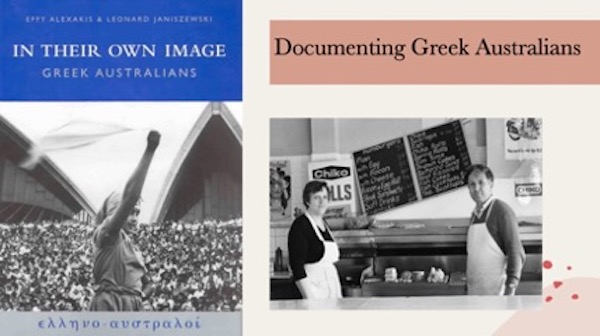

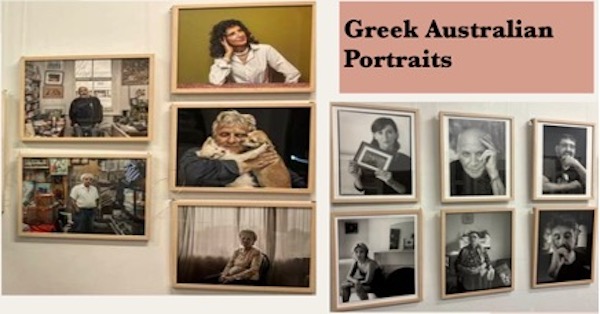

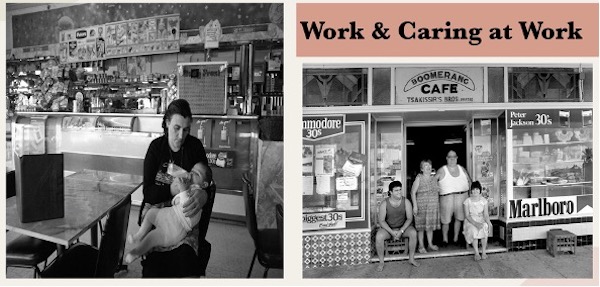

The fact that the cultural production of Greek Melbourne often connects with broader Greek Australian self-representation guides me to start my cultural mapping with a lasting nationwide project. It is about the work of Effy Alexakis, a Sydney-based Greek Australian photographer who has earned accolades in Australia and Greece, and Leonard Janiszewski, a public historian. For more than 40 years, Alexakis and Janiszewski have been traveling across the continent documenting the faces, bodies, words and worlds of migrants and their children, including Greek Melbournians, narrating their experiences.

Alexakis frames her subjects in the tradition of portraiture. Her camera zooms on her subjects at work or leisure. Its focus brings the viewer into a face-to-face observation of her subjects as human beings. This framing is not merely aesthetic; it does not just concern itself with perspective, angle, shades, and light. As art critics note, “portraiture stands apart from other genres of art as it marks the intersection between portrait, biography and history. They are more than artworks; when people look at portraits, they think they are encountering that person.”

In this respect, Alexakis and Janiszewski’s project performs political work. Greek Australia has fresh memories of being labeled as “wog,” a racial slur devaluing southern Europeans as lesser human beings. Thus, the act of humanizing the migrants in photography connects with the politics of representing Otherness in Australia in a manner which undermines ethnic and racial hierarchies pointing to the migrants’ shared humanness.

Opening an exhibit of Alexakis’s photography in Melbourne, historian Andonis Piperoglou adds another layer to the photographer’s choice of subjects. “She takes portraits with her subjects,” he notes, “she does not merely take pictures of them. … Engaging with a range of subjects … [she] manages to reorient common assumptions about migrant pasts … we see how Greek-Australianness is alive in difference. How Greek-Australianness is alive in diversity.”

Greek-Australianness alive in diversity … All of us—educators, poets, researchers, artists, community leaders, documentary makers—who engage in the business of bringing migrant and diasporic histories and cultures into representation confront this question: How do we do justice to the enormous complexities of a diaspora, how do we narrate it in an ethical and politically responsible manner?

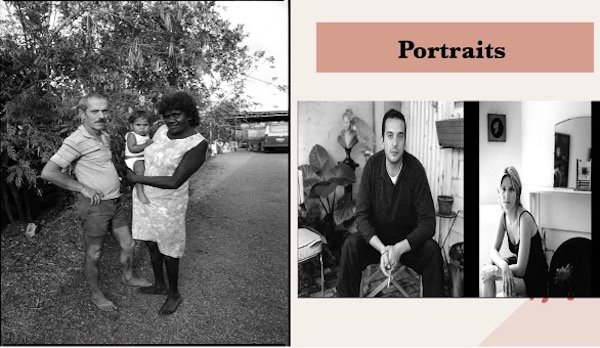

Alexakis’s corpus answers this question in a manner we could call an “ethic of inclusion.” For her, to document Greek Australia is to recognize its internal diversity. She practices a form of ethnographic realism that renders visible the worker, the cook, the store owner, those who marry across cultural and racial ethnicities, and public figures who are known for their non-normative sexualities. Instead of eliding heterogeneity her cartography foregrounds its images and textures. We are far away here from representations reducing diasporic identities to a single social type—something that Greek American narratives perform repeatedly. A diaspora, after all, is a cultural field crisscrossed with diversity.

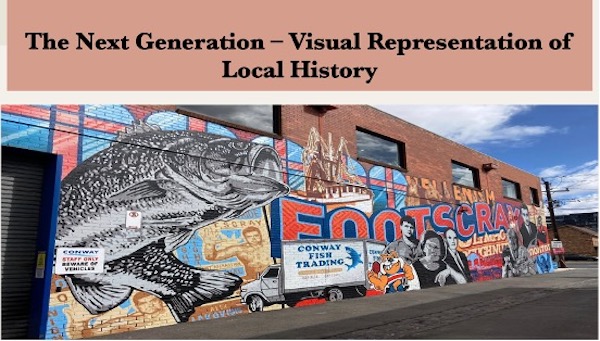

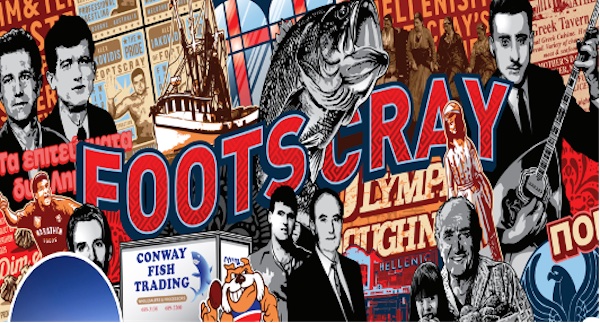

If Alexakis produces Greek Australia at a national scale, a mural in Melbourne produces memories at a local level. The mural is located in the suburb of Footscray, which had a high migrant concentration in the past. It was created by a Greek Australian youth collective that goes by the name of Yitonia. The mural is a bricolage of historical references to Footscray’s community, business trades, sports, and entertainment.

The rich iconography will most certainly puzzle an outside viewer given that one needs local knowledge to decode it. Images associated with fishing and the fish industry prevail, referring to a major economic activity of immigrants in the past. Visual references to the local football team and athletes are multiple. There is a father and his daughter, and several images of individuals connected with migration. They represent important immigrant figures, I was told. The image of the bouzouki player is an unmistakable reference to the presence of the Greek rembetiko in the neighborhood. The mural incorporates Greek immigrants and cultures in the local history of a suburb.

How does this unassuming visual representation contribute to a new diasporic cartography? The following commentary by poet and playwright Konstantinos Kalymnios, published in the Melbournian Neos Kosmos, provides an answer:

The mural can be interpreted as a profound symbol as a way of re-configuring the relevance of Hellenism to Melbourne by moving away from a narrow identification of Greeks via their place of origin within Greece, an increasingly obscure and futile endeavour considering how few of the latter generations identify in any meaningful way with their grandparents’ birthplace, to a local identity, which is rooted in the experiences and interactions of those who actually live in that area, making these relevant to all those who still remain in, or identify with that area, considering that many of those who do so, have moved out of the suburb, some photos and a lingering affection for the local football team the most enduring ties to the place of their own personal migrant foundation myth.

This is a paean to a Hellenism that no longer exists and its memory is fading. The few Greeks that remain in the area remember. Their children may not and their grandchildren are largely blissfully unaware of their existence. Some of the businesses commemorated in the mural are of broader importance and yet remain a lesson in futility. Jack Dardalis’ success in Marathon Foods enabled him to make possible the creation of the National Centre for Hellenic Studies and Research (EKEME), an endeavour which ultimately failed. Other businesses’ such as the Goulas’ family’s Conway’s Fish Trading is still known for its philanthropy. Kotsianis has therefore conjured up the ghosts of Hellenisms past to haunt us, to remind us who we once were, what we once did.

The mural is a non-monumental memorial to the migrant past. Although it is seen as a memorial to Hellenism, there is no monumental reference to it—there is no Acropolis, no ancient ruins, no whitewashed island villages. No Aegean blue. Instead, its “earth colours of red and white reference a Hellenism that is at one with the local landscape.” Here we witness an unambiguous articulation of a cartography that places the local as the diasporic center. The next generation pays homage to a lived-in reality that shaped their migrant parents and themselves as Greek Australian children.

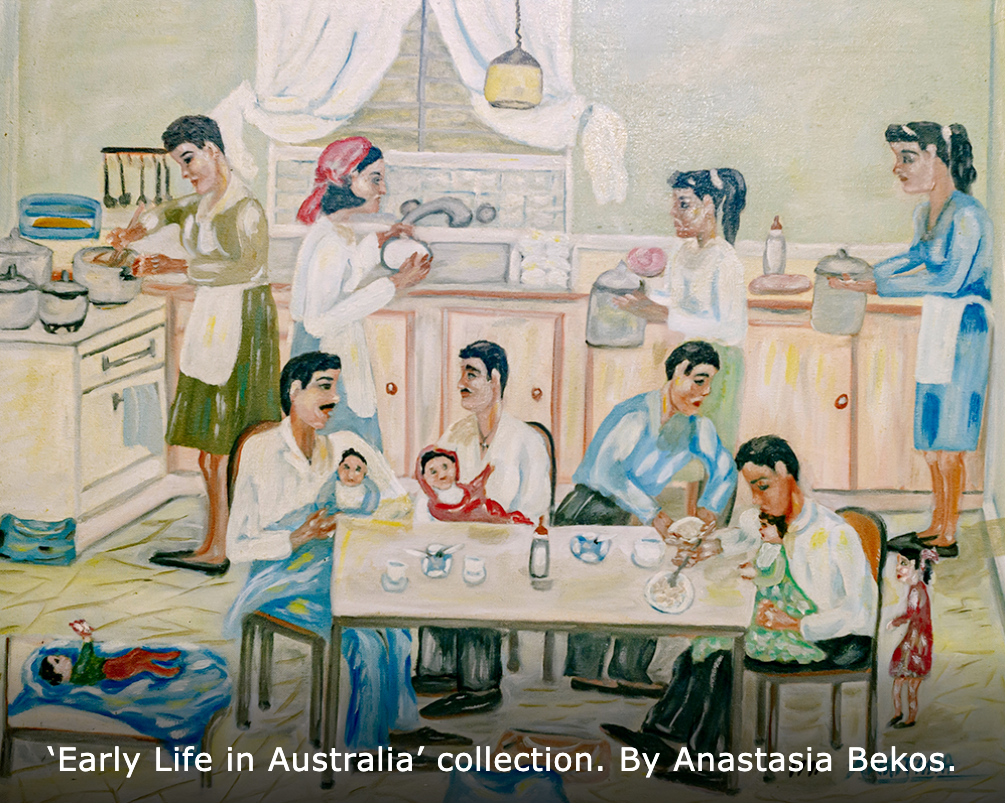

So, how do we memorialize our cultural past and present? When we think of migrant material culture, we often conjure images of embroideries, musical instruments, folk costumes, photographs, flags, or religious icons. But another element, inextricably connected with the migrant experience, is often neglected. I refer to objects utilized for daily meal preparations—pots, frying pans, kettles. In Greek immigrant culture, where homemade food carries high value, these objects not only sustain the family but contribute to culinary cultural continuity. The cooking ware demands continuous labor: washing, scraping, and maintaining to maximize their life span in conditions of poverty. Cooking utensils are a part of a necessary domestic ritual, primarily associated with women’s work.

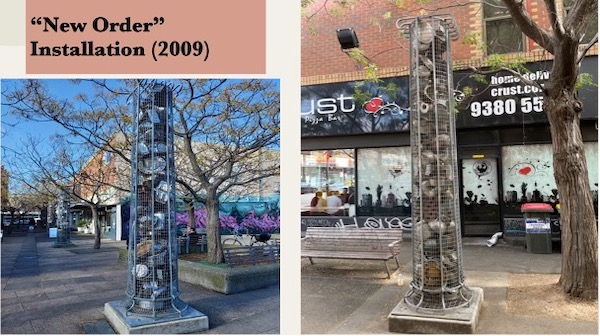

This mundane reality is memorialized in an artwork entitled the “New Order.” It is installed in the suburb of Brunswick, in a square called “The Sparta Place,” a transnational space that accentuates the relationship between this locale and the city of Sparta. The bust of Spartan leader Leonidas offers an iconic representation of this relationship.

The “New Order” does reference the ancient past. The installation consists of five freestanding columns that evoke “ruined remains” from ancient Greece. But it injects a new element to this conventional theme. “The form of each Greek-style column is delineated by a cage of galvanized steel uprights and mesh. The cages are filled with recycled ‘kitchenalia’ toasters, kettles, saucepans, mixing bowls, teapots, etc., made from various materials, including stainless steel, chrome, and aluminum. …; a portion of the kitchenalia was donated by members of the local community.”

Placed next to the statue of Leonidas, this diasporic public space juxtaposes two kinds of pasts: the monumental presence of ancient Greece—a staple of national and ethnic identity; and the display of humble yet vital material culture that connects with the immigrants. The columns monumentalize domestic migrant labor. The classical and the mundane, high culture and low culture—the prestigious and the humble past blur in a manner that some in this audience might call a postmodern cultural expression.

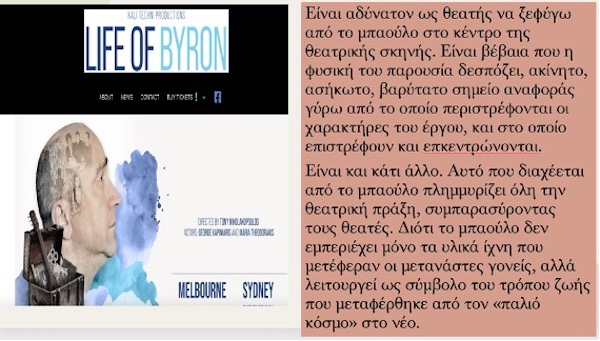

But the immigrant past is not idealized. In Melbourne, I attended the theatrical play Byron’s Life, an example of the “growing-up Greek” genre. Moved by its viewing, I shared the following on my facebook page: The play dramatizes the dilemmas, ambivalences, and anxieties of a Greek Australian male who negotiates the expectations of the surrounding migrant culture; his struggle to find a measure of balance between the Australian culture pulling him toward one direction and his “Old World” surroundings toward another. In the poster, we see the centrality of the immigrant trunk in the family’s living room, symbolic of the overwhelming domestic presence of immigrant culture that the next generation must come to terms with.

In yet another example, Konstantinos Kalymnios’ play “Opou Gis kai Patris,” exemplifies the phenomenon of diaspora exporting its cultural production to Greece.

The play offers a textbook case of multidirectional transnational flows: A comedy about the Greek Australian immigrant experience written in Greek by a Melbourne-based author, making its debut on stage in Athens by Greek actors and actresses, and then “returning” to Australia with performances by the Athenian troupe in Sydney and Melbourne, in Greek with English subtitles. Reviews were published in both Greece and Greek Australia. The diaspora is exporting its narratives and reimporting them––certainly a subject for an article…

A thriving center of Hellenism produces notable literature. Melbourne-born novelist Christos Tsiolkas has earned international acclaim. His fiction explores intergenerational and intradiasporic tensions and conflicts.

The poet π.O., barely known in Greece, is “a legendary figure in the Australian poetry scene” and a chronicler of Melbourne and its culture and migrations.” His poetry performs diasporic bilingualism as a play between languages, a coexistence where languages in juxtaposition interact creatively with each other.

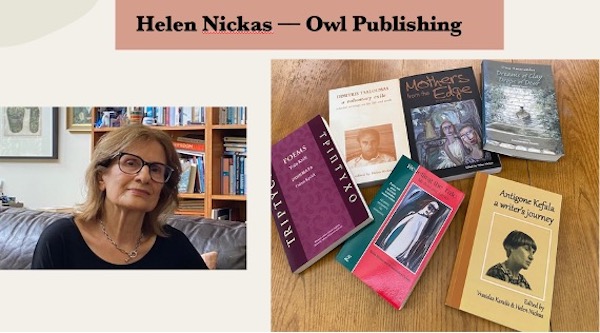

In 1992, author and educator Helen Nickas founded Owl Publishing in Melbourne, a venue aiming “to nurture, study, translate and disseminate Greek-Australian literature.”

The online magazine Kalliope X contributes Greek poetry and supports multicultural writing. The literary journal Antipodes, launched in 1974, is “the longest published, bilingual periodical circulating in Australia.”

A community cannot claim itself as a center without an understanding of itself. The official Community operates a forum—Greek History and Culture Seminars—for the purpose of sharing scholarly research with the public. Building bridges between academics and the community, the forum features scholars from Greece, the United States, and Australia. Greek Australian topics are numerous. It creates a public forum for discussion and debate, contributing to a self-reflexive public sphere—though the in-person attendance, I was told, has decreased significantly after Covid.

An indicator of the Community’s support of academic work is its contributing to the establishment of a Senior Hellenic Lecturer in Global Diasporas at the University of Melbourne, the first of its kind in the world.

Melbourne’s diasporic identity raises the question of its relations with Australia and Greece. In the interest of time, I will only identify one thread, civic engagement, by which I broadly mean historically knowledgeable citizens displaying an interest in the issues of the polis.

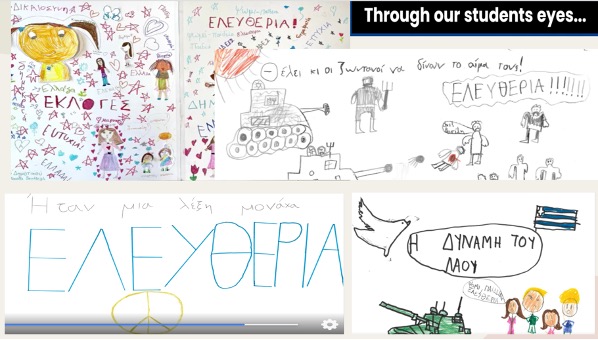

In relation to Greece, this civic component was performed in the community’s language schools to honor the 50th year of the student uprising in the Athens Polytechnic against the dictatorship. The commemoration involved songs, plays, and visual representations around the theme of “commitment to freedom.” The events cultivate historical memory and convey the civic message of active opposition to authoritarianism.

In relation to Australia, Greek diasporic citizenship was expressed in connection to a 2023 national referendum where citizens were asked to consider the creation “of a consultative body to the federal parliament and the federal government … which is to give advice on issues affecting the lives of Indigenous Australians.”

The community participated in the national debate via at least two platforms. The first was a talk sponsored by the Greek Community of Melbourne, entitled “Greek Lives on Indigenous Lands: Community Responsibility and the Ethnic Experience of Coloniality.” The second was the participation of Greek Australians in a rally supporting the referendum under the banner of their diasporic identity.

Here, we witness an expansion of what it means to be diasporic. Sectors of Greek Australia do not see themselves as merely an ethnic or ethnoreligious group. They engage politically as diasporic citizens who are involved in understanding and shaping their home society.5 Their centeredness involves political agency at their home.

To start moving toward a conclusion: Greek Melbourne offers an example of a diaspora-centered identity project. A critical mass of artists, authors, academics, journalists, and educators engage with the community’s history and contemporary culture. It is a form of labor—we could call it cultural activism—that creates a multifaceted cartography. It consists of staging plays, designing murals and installations with Greek Melbournian themes, exhibiting photography, organizing film festivals, creating venues for literature and poetry, and coordinating community-sponsored seminars hosting academics. This work explores and expresses the migrant and diasporic experience and makes efforts to sustain a rigorous public sphere to reflect on the issues it confronts. It is a practice directed toward αυτογνωσία and critical self-reflection. It is guided by the ethic of inclusion, the production of historical memory, and broadly the cultivation of cultural education.

Diasporas require vast cultural and material labor for their production. In fact, we could think of diaspora as labor. This is because diasporic institutions and identities cannot be taken for granted. Diasporas continuously negotiate new conditions, respond to new challenges, and, in turn, need to reinvent themselves anew. They require the involvement of the next generation. It is this condition that feeds a feeling that is an inextricable component of a diaspora: the concern, even anxiety, about its future.

A recurrent topic of conversation among Greek Melbournians I spoke with was precisely this concern. Will there be a new generation of journalists, artists, scholars, and educators to keep documenting, reflecting, and interpreting the ever-changing diaspora? Who will be creating and curating the archives? Will there be a museum and a center of diaspora studies? Will there be rigorous public deliberation and debate on these questions in the media, cultural commentary, and identity narratives? Will the ethic of inclusion persist, or will it be eclipsed by one-dimensional representation? Will there be a public invested in this kind of self-reflection? We are preoccupied with cultural reproduction, but do we really understand the next generation?

Two weeks after returning to Columbus, my home base, I received several packages of books mailed by Helen Nickas, a literary critic and editor I mentioned earlier. They contained the corpus of her lifetime’s work as an editor.

Moved by this gift, I created a special section in my library to host it. The books represent tangible, material evidence of a life devoted to expanding the diaspora’s literary cartography.

I often touch the spine of each book she gifted me to make a tactile connection with a tiny sample of a diaspora’s vast but underexplored archive. I ask myself: What do we owe to this archive?

And more broadly, what is our obligation to the Greek diasporic presence and future in any global city? What is our responsibility as diasporic citizens, educators, and institutions? What kinds of cultural projects do we deem worthy of Greek New York City?

There are no easy answers. Greek Melbourne offers a vision of inclusion, and the importance of diasporic labor in arts and learning to assert a robust cultural presence in a city’s fabric. Cultural activism is paramount in this project, Greek Melbourne reminds us, but it cannot be done without institutional support. One thing is for sure, as the conversation is moving toward “global Hellenism,” Greek Melbourne beckons us to pluralize Hellenisms and focus on their regional historical and cultural specificities. How we go about it requires another conversation, yet another layer of cultural labor.

Thank you for your attention, I look forward to the conversation.

September 3, 2024

Yiorgos Anagnostou lives and works in Columbus, Ohio.

Notes

1. The "Themis Brown Memorial Lecture," The Center for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies of Queens College (March 7, 2024) and the Center for Hellenic Studies, Stony Brook University (March 8, 2024). The talk in the latter was adjusted for a student audience. I thank Gerasimus Katsan (Queens College) and Stella Tsirka (Stony Brook U) for the invitations. I express my appreciation to Maria Athanasopoulou for her help in promoting and organizing both events.

2. For an introduction of this cultural mapping in the Greek media see, Γιώργος Αναγνώστου, 2023. «Η Νέα Χαρτογράφηση της Διασποράς στη Μελβούρνη». ΒΗΜAgazino, 22 Οκτώβρη.

3. I thank the CASS Foundation for making my visit possible via The Walter Mangold Fellowship (October and November 2023), and Dr. Andonis Piperoglou, Senior Hellenic Lecturer in Global Diasporas at the University of Melbourne, for hosting me and the intellectual engagement. I am indebted to Dr. Nick Dallas for the memorable hospitality. Memories of conversations with numerous individuals generous in the sharing of their ideas still guide my thinking about diaspora. I extend my appreciation to all.

4. On the Greek state’s paternalism regarding “the diaspora” see Lina Venturas, 2009. “‘Deterritorialising’ the Nation: the Greek State and ‘Ecumenical Hellenism.’” In Greek Migration and Migration since 1700, edited by Dimitris Tziovas, 125–40. Ashgate.

5. See Yiorgos Anagnostou, 2023. “Recontextualizing the Bicentenary in Greek America and Beyond: Greek Civic Identities in the Diaspora.” In The Greek Revolution and the Greek Diaspora in the United States, edited by Maria Kaliambou, 86–102. New York: Routledge.