The Signatures of a Time and a Place in the World

George Kouvaros

Editor’s note: In late March 2023, after visiting the photography exhibition Gather Together: Chicago Street Photography by Diane Alexander White at the National Hellenic Museum in Chicago, I invited Dr. George Kouvaros, Professor of Film Studies in the School of the Arts and Media at the UNSW in Sydney, Australia, to share his thoughts about the images. The spur for extending the invitation was Professor Kouvaros’ discussion of the connections between photography and diasporic life in his 2018 book, The Old Greeks: Photography, Cinema, Migration. The essay below is the result of this transoceanic exchange, crafted in an epistolary form.

Dear Yiorgos

Thank you for drawing my attention to the exhibition Gather Together: Chicago Street Photography by Diane Alexander White. You had in mind an essay. This is something that I’m happy to provide, with the proviso that it retains the context of your invitation. The reasons for this may be a little unclear. They are to do with the fact that I’m writing these words a long way from the urban settings depicted in the photographs. The upside of resisting the temptation to place myself where I am not, is that it allows me to speak more directly about those aspects of the images that connect with the representation of community by photographers here in Australia. Indeed, much of what interests me about these images concerns a matter that spans different histories and cultures of migration: how one generation situates itself in relation to a previous generation and what this reveals about the nature of diasporic life.

The other reason is to signal that my thoughts on the exhibition are influenced by your own work—in particular, your discussion of community as the product of a series of inclusions and exclusions, adaptations and reworkings that belie the tendency to see it as fixed and monolithic. Our attachment to the community is, as you point out, always “partial” in its operations, dispersed across a range of activities and sites—“The church, meetings of organisations, the festival, the classroom, the social dance, the choir.” These ideas underpin a more recent essay of yours on Dimitri Mellos’ photographs of Greek Independence Day Parades. What follows, then, is an indirect dialogue with the ideas raised in this work that, I hope, fulfills the intention of your invitation and adds to a larger discussion about the vicissitudes of diasporic belonging.

****

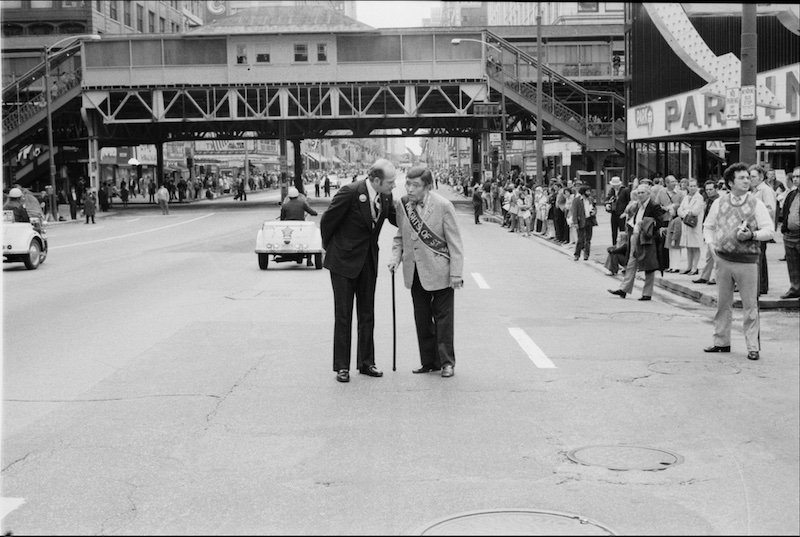

The first thing to note about the photographs is when they were taken: apart from a small handful that show an “Indo-Pak Parade” in 2009, all span the period from 1976 to 1981. To bring this into relief, the commencement of World War II was as proximate to the events depicted as our present day is to them. Noting this helps to situate the photographs while also drawing attention to those aspects of the celebrations that strike one as familiar. To be sure, there is a lot that is familiar here. As you note in the essay on Mellos’ images, the claims made by ethnic parades tend to be distinctly uniform: “They assert collective identity and re-enact the national narrative of cultural continuity, love for the nation, and civilizational success.” By placing the images of Greek Independence Day Parades alongside a smattering of images that show other forms of national commemoration—Festa Italiana, St Patrick’s Day, Puerto Rican Festival, Japanese Festival, Mexican Civic Society Parade, Von Steuben Day Parade—Gather Together locates the display of Greek collective identity as part of a broader push for ethnic visibility, that, in the United States, occurred in the context of the rise of minority rights, and, in Australia, was facilitated by the emergence of Multiculturalism as government policy. The photographs evidence how these developments translated into occasions in which, as you note, ethnic peoples partake in the pleasures of gazing at the members of their group “parading in front of their eyes.” And far from offering a rendition of ethnicity that is simply the re-enactment of the same, the photographs draw attention to those social and political markers that allow the observer to locate the parade at a particular point in the community’s history.

The questions that tend to follow these observations address the matter of who is part of the display of cultural identity and who is left out. What aspects of a community’s history and aspirations are made visible and what are withheld?

These questions affirm the status of the photographs as social documents. Now, as important as this approach is, I’m guessing, Yiorgos, that you did not extend the invitation on the basis of what I might contribute to its pursuit. More in line with the issues that dominate my writings is the matter of how the rendition of community life evident in the images intersects with and is informed by the history of visual culture. Making sense of this relationship requires that we treat the photographs not as illustrations of predetermined meanings—or even as reference points that particularize the abstractions that dominate discussions of community life. Rather, it requires that we treat these images as sites where diasporic existence as a lived event comes into view. Underpinning this approach is the dictum that I have long held to in my work, namely, that media do more than inform the movement and settlement of peoples. They determine how these activities are understood.

Evidencing this claim requires us to follow two interrelated lines of thought. The first involves the lead provided by the photographer, herself, and situating the images in Gather Together within the tradition of street photography. Far from being a uniquely American phenomenon, the view of metropolitan life associated with this style of photography was shaped by the work of European figures such as Eugène Atget, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Bill Brandt, André Kertész and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The work of home-grown exponents such as Alfred Stieglitz, Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Berenice Abbott and Helen Levitt occurred in conversation with the work of their European counterparts. But such was the cultural and economic pull exerted by the United States that, by the second half of the twentieth-century, street photography, as a way of engaging with the currents of urban life, was intimately linked to metropolitan centres such as Chicago, New York and Los Angeles. Importantly, this would not have been possible without migration. I’m thinking of those emigree photographers who arrived in the United States from Europe during the lead-up to World War II—for example, Lisette Model, Josef Breitenbach, Erwin Blumenfeld, Hermann Landshoff, John Gutmann and George Grosz—as well as those individuals whose parents or grandparents had been part of the wave of migration that spanned the final decades of the nineteenth-century and peaked in 1907, for example, William Klein, Saul Leiter and Eve Arnold.

Drawing attention to these migrations frames the history of photography as a transcultural history. For our purposes, it also introduces a crucial inflexion in how we determine the photographic allure of the street—as both a setting for the performance of public identity and as a dramatis personae, in its own right. On the one hand, the endless traffic of bodies generates an array of moments when the gestures and ways of being that define this performance are brought into relief. On the other, it provides a ready-made occasion for the photographer to locate herself within the city’s hustle and flow. A fine example are the images in Model’s photographic series Running Legs (1940-1941) that show in close-up the legs and shoes of the city’s commuters. Model’s images interlace feelings of displacement with a wry acknowledgement of the sense of anonymity that characterizes life in the metropolis. The same forces that drew photographers to explore the rhythms of street life also underpin the popularity of street parades and public rallies. The jamming together of bodies on the sidewalk or parading along the road provides perfect cover as well as a series of interrelated zones of activity on which to train the camera’s lens. With so much going on, the photographer can switch from photographing the spectacle of the parade to photographing the parade’s audience and use this switching of perspective to draw out the undercurrents that characterise such events.

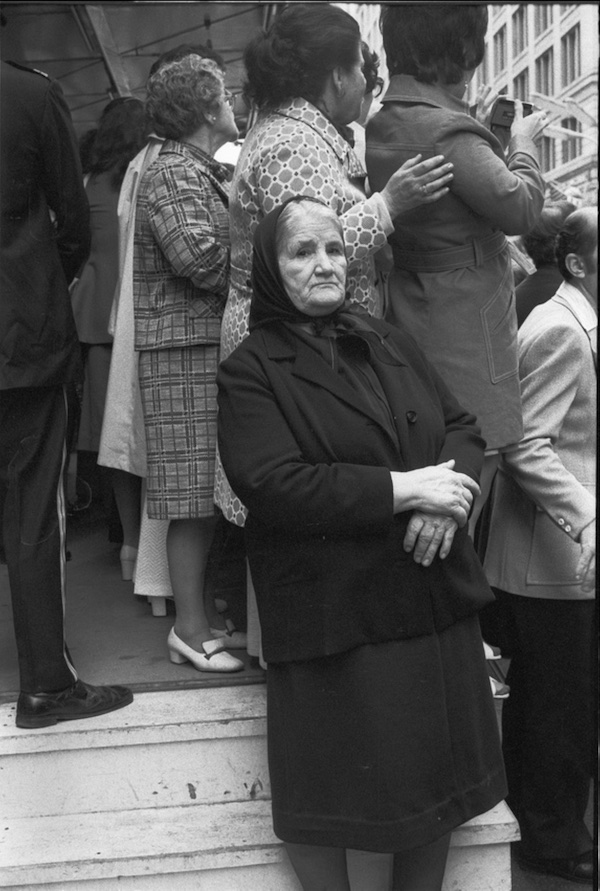

In the essay on Mellos’ photographs, you identify the photographer’s interest in activities taking place “to the side” or “backstage”: locations where the camera’s gaze encounters the humanity of the parade’s participants head on and where “an informal sociability” takes precedence over the pomp and ceremony of the main event. In Gather Together this realignment of perspective is more understated. Rather than searching out areas backstage or to the side of the event, the photographer focuses on faces in the crowd, either looking straight back at the camera or gazing past it, toward the spectacle occurring behind her back. Her approach is observational: less driven by an interest in the contrapuntal energies of moments “in-between” the hoopla, more willing to allow the external markers of a period—hairstyles, ways of dressing, facial expressions—to do their work in switching our attention away from the assertions of cultural identity broadcast by the parade to the time-bound nature of the gathering. Indeed, more than forty years after their taking, a major part of the impact of the photographs lies in the way in which these external markers convey an unsettling recognition of the transient nature of all social configurations.

This is the second line of thought required to understand the photographs on show at the National Hellenic Museum, one that considers how photography encodes a certain rendition of everyday life as time-bound. This line of thought can be pursued at various points in the twin histories that we have been pursuing: the history of mass migration and the history of photography’s evolution as a medium. For our purposes, it makes sense to focus on the period leading up to the years when the photographs in Gather Together were taken. Doing so draws into our discussion the work of a young Swiss photographer who arrived in New York in 1947: Robert Frank. The images in Frank’s 1958 photo-book Les Américains (The Americans) convey states of being that affirm the instability of everyday life. This is a matter of both what the images show—expressions of lassitude, blankness, fatigue—and the deceptively uncomposed and elliptical way in which these things are shown. In “Parade–Hoboken, New Jersey,” “Political Rally–Chicago,” “Convention Hall–Chicago” the outward display of collective life reveals itself as a tentative and ill-fitting arrangement of postures and assertions. The feelings of disquiet that mark the faces in these photographs have as their distinguishing feature Frank’s ability to immerse himself in the spectacle while also working in counterpoint to its carefully rehearsed timings.

One of the book’s most famous images—“Elevator–Miami Beach”—is taken from inside an elevator. In the foreground, a blurred figure in a while fur shawl is exiting; behind her, another shadowy figure is heading toward the doors. Sandwiched between these two bodies, the elevator operator waits and stares at nothing in particular. In a sense, this is exactly what the photographer is doing, except that Frank places these moments of nothing-in-particular at the centre of his approach. In the image of the elevator operator, both the photographer and subject are immersed in a flow of activity that defies the possibility of formal balance. The blurring of movement, general graininess and uneven exposure register time as a disruptive force that surrounds both the subject and photographer. Time affects a disturbance of gesture. But it also gives rise to new gestures: gestures of distraction and uncertainty that evoke the way time inhabits us. The outcome is both a challenge to post-war narratives of social harmony and a reenergizing of the vernacular that draws on the capacity of photographic images to show us everyday life from the ground up.

The most influential account of the implications of this view of things is found in the work of another emigre to the United States, Siegfried Kracauer. In his book Theory of Film, published in 1960, Kracauer locates the value of both photography and film in their capacity to shift our relationship to what he terms “physical reality”: “Film renders visible what we did not, or perhaps even could not, see before its advent. It effectively assists us in discovering the material world with its psychophysical correspondences.” For Kracauer, the camera’s view of the world enables an engagement with the rhythms and energies of everyday life that affect the spectator at the level of not just sight, but also at a broader physiological level. The matter of whether or not this potential is realized hinges on the harnessing of certain types of content. “Since any medium is partial to the things it is uniquely equipped to render, the cinema is conceivably animated by a desire to picture transient material life, life at its most ephemeral. Street crowds, involuntary gestures, and other fleeting impressions are its very meat.” The pay-off for exploiting this potential is a much richer engagement with those discontinuous forces and fleeting encounters that highlight the provisional nature of human existence.

Near the end of the book, Kracauer returns to the social value of photographic media. To put it too baldly, film and photography provide an antidote to a twin problem that characterizes modern society: a tendency of the sciences to sideline ordinary experience for the sake of mathematical exactitude and a widespread disbelief in the validity of guiding norms. They do so by providing the viewer with an “experience of things in their concreteness.”

In recording and exploring physical reality, film exposes to view a world never seen before, a world as elusive as [Edgar Allan] Poe’s purloined letter, which cannot be found because it is within everybody’s reach. What is meant here is of course not any of those extensions of the everyday world which are being annexed by science but our ordinary physical environment itself. Strange as it may seem, although streets, faces, railway stations, etc., lie before our eyes, they have remained largely invisible so far.

He concludes by aligning two states whose affiliation will become prominent in his final unfinished writings on history: the reengagement with material reality enabled by film and photography and the feelings of territorial displacement that characterize the situation faced by the new arrival. The pull into the realm of material life exercised by film and photography is simultaneously a push out into the world. “So they help us not only to appreciate our given material environment but to extend it in all directions. They virtually make the world our home.”

In Kracauer’s writings, the affective capacities of photographic media and the displacements that characterize migration are not simply concurrent. They are the twin elements of the one compound. His injunctions prioritize those styles and subject matter where this affiliation comes to the fore. Hence, his constant evocation of the figure of the street, as both an actual space that is open to the flow of life and as a means for the subject to take stock. “The street in the extended sense of the word is not only the arena of fleeting impressions and chance encounters but a place where the flow of life is bound to assert itself.” Immediately following this statement, he specifies that within this movement of elements the observer is able to draw out a story, but one in which “an incessant flow of possibilities and near-intangible meanings appears.” The capacity of film and photography to extend our material environment is, thus, also, an opportunity to locate ourselves in the world in a manner that does not deny the feelings of contingency and displacement that have as their exemplar the situation of migration, but takes them as a starting point.

****

I hope it’s clear, Yiorgos, that, in a roundabout manner, we have returned to a matter that is central to the images in Gather Together as well as your own writings: the inherently unstable nature of community formation. The rendition of the ethnic community in the exhibition is affecting not because it shows us something that is timeless. Rather, it is because it frames the desire for connection as time-bound, one that is formed in the context of an encounter—on the part of the photographer and the viewer—with the provisionality of the events rendered by the camera. The photographs allow us to situate the politically crucial action of claiming visibility and asserting community identity in the context of forces that render all such claims contingent. In so doing, they work against those aspects of the community’s operations that tip toward the proprietorial and exclusionary while at the same time grounding our experience of everyday life in what the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy calls “the interruption of singularities.”

In a short account of Walker Evans’ photographs of the faces of New York subway commuters captured by a 35 mm camera hidden in his coat pocket, the writer James Agee puts this more directly. He identifies in Evans’ portraits both a vast gallery of social types and the imprints of a unique life: “Each carries in the postures of his body, in his hands, in his face, in the eyes, the signatures of a time and place in the world.” This is what I see in the photographs at the National Hellenic Museum: time and place as contingent. Community as something that is formed and re-formed on-the-spot and in response to the energies and rhythms that are part of the flow of life. To claim otherwise is to deny these images their status as photographs and strip the community of the social, cultural and material forces that are essential to our being with others.

****

The matter that I have yet to address is the one signalled right at the start: the distinctly generational rendition of community on show in the photographs. To frame this matter as simply as possible, the photographs in Gather Together were produced by a young college-educated woman who identifies as part of the community, seeks to celebrate its vitality and success in achieving a level of public recognition, but, in the act of picking up the camera and using it to record the people, places and events that constitute its life, distances herself from its operations. To be clear: distancing is not rejecting. Rather, it’s how we create the space necessary to reassess our relationship to the community—to make a choice as to what to keep and what to let go. How else is one to survive as a second-generation Greek-American woman amid the tumult of the 1970s and early 1980s? How else to navigate between the traditions and beliefs of one’s forebears and the social worlds enabled by their labour?

This is another way we can understand the strategy discussed earlier whereby the photographer positions herself in the middle. But this time the activity of mediation is inherent to the larger context of the photographs, their circulation within a network of events—cultural, personal, familial—that connect the moment of their taking to the on-going moment of their viewing. In the remarks that follow, Yiorgos, I want to illustrate what is at stake in this circulation by referring to the work of a Greek-Australian photographer that brings these generational reverberations into the space of the image, itself: Elizabeth Gertsakis.

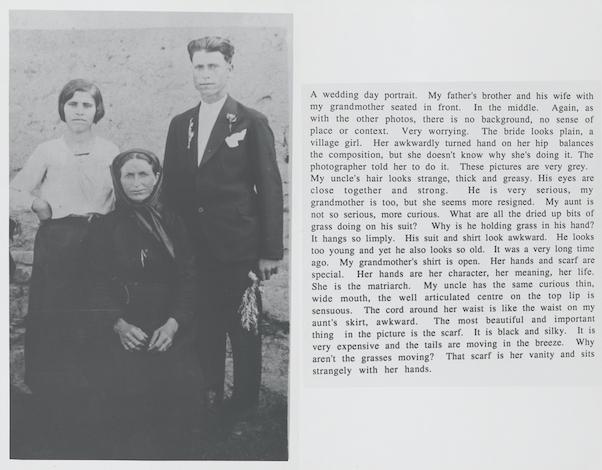

In Innocent Reading for Origin Gertsakis photographs a series of black and white snapshots that span the period prior to and just after her parents’ emigration from Florina to Melbourne. Alongside these photographs, she transcribes basic contextual information as well as her thoughts and responses to the images. “A wedding day portrait,” she writes about one of the photographs. “My father’s brother and his wife with my grandmother seated in front.” Yet the more she looks at the image the more that certain details expose the gaps in her knowledge. These gaps take the form of questions. “What are all the dried up bits of grass doing on his suit?” she asks about her uncle. “Why is he holding grass in his hand?”

These questions dramatize the distance between then and now, between the moment captured in the photographs of the family members looking back at the camera and the present moment of viewing. The photographs collapse this distance or, at least, provoke the sensation that it might be overcome. They do this at the same time as they draw attention to those elements of the past that remain unknowable. The written text transforms these elements into objects of a strange curiosity. “My mother looks very young,” she writes about a photograph showing her mother and aunt standing together outside a house. “She has big slippers on. Would they get dirty on the road? My aunt has special shoes and very slippery stockings. Their dresses have too many buttons. The buildings look dirty and old. This is a special picture. They stand in a special way.”

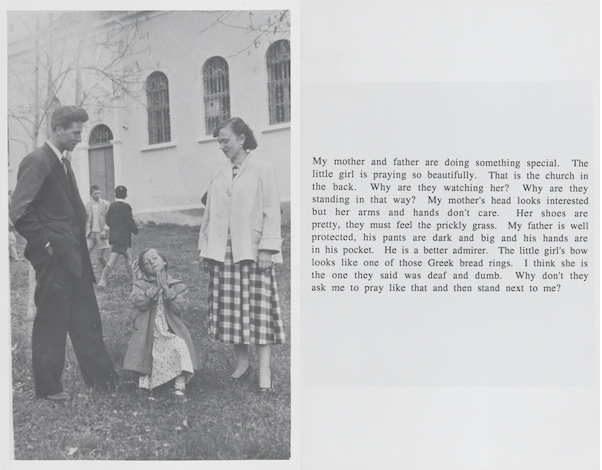

In a deceptively simple manner, Gertsakis’ work establishes a series of affinities between photography, a vision of history as unknowable, and an experience of migration marked by the failure of things to carry over and survive the uprooting. In one of the images, the photographer’s mother and father are standing either side of a small girl whose hands are clasped in prayer. “The little girl is praying so beautifully,” Gertsakis writes. “That is the church in the back. Why are they watching her? Why are they standing in that way?” After analyzing the postures and clothing of the two adults, her attention turns back to the little girl: “I think she is the one they said was deaf and dumb. Why don’t they ask me to pray like that and then stand next to me?” The threat of being rendered deaf and dumb is what haunts the photographer’s own struggle to speak well of the past. Positioned between the two adults, the little girl kneeling in supplication functions as a link between past and present, between one generation and the next. As someone who experienced the dislocations of migration first-hand yet because of her age was sheltered from many of its consequences, the photographer shares this disposition. Working in tandem with the written text, the photographs are like meeting points in which the lives of those in the picture and those looking on are brought together in a story of recognition and misrecognition.

Looking at Gertsakis’ images in light of your invitation, Yiorgos, it strikes me that these feelings of displacement are part of a generational drama that operates not just at the level of the individual family unit, but also the collective grouping that we refer to as community. The challenges that inform the life of the ethnic community, the photographs suggest, go beyond achieving visibility or determining whose histories and experiences are included in its narratives and whose are left out. They are also to do with the gaps and lacuna that determine how one generation understands its place in relationship to a previous generation. This is another way to view our connection to community as “partial.” The community is where we encounter an otherness that has made its home within us. Taking this on board means shifting the basis of a community from a common ethnicity or race to a shared experience of limits. This is how Nancy understands the pull of community: as a space where the encounter with the other’s alterity both affirms and delimits our singularity. “I experience alterity in the other together with the alteration that ‘in me’ sets my singularity outside me and infinitely delimits it.” Community, he goes on to propose, is where the same and the other partake “in the sharing of identity.”

This is why my final words, Yiorgos, take the form of a series of questions, to you as well as others who have wrestled with these matters. Is it possible to imagine forms of communal engagement that place this experience of limits at the centre of their operations? How might we narrate the emotions and affects generated as a consequence? What media are best suited to such an effort? These are complex questions. But looking at the photographs in Gather Together and Innocent Reading for Origin, I would venture that the outlines of an answer might be right there, in front of our eyes.

Yours truly

George

May 26, 2023.

George Kouvaros is Professor of Film Studies in the School of the Arts and Media, UNSW. His most recent book is The Old Greeks: Photography, Cinema, Migration (University of Western Australia Press, 2018). In 2020, along with Professor Nicholas Doumanis, he was awarded an Australian Research Council Linkage Grant for the project “Remembering Sydney’s Post-war Greek Neighbourhoods, 1949-1972.” In partnership with the State Library of New South Wales, UNSW and the Greek Orthodox Community of New South Wales, this grant is being used to fund the creation of the Greek-Australian Archive.

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009).

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. “The Greek Independence Day Parade: Ways of Seeing and Imagining.” Ergon: Greek/American and Diaspora Arts and Letters, May 1, 2018. https://ergon.scienzine.com/article/essays/ways-of-seeing-and-imagining

Evans, Walker. Many Are Called. Introduction by James Agee. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004).

Kracauer, Siegfried. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960).

Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Inoperative Community (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1991).

Editor’s Note: For an Ergon interview with Diane Alexander White see here.