In Focus: Diane Alexander White Photography

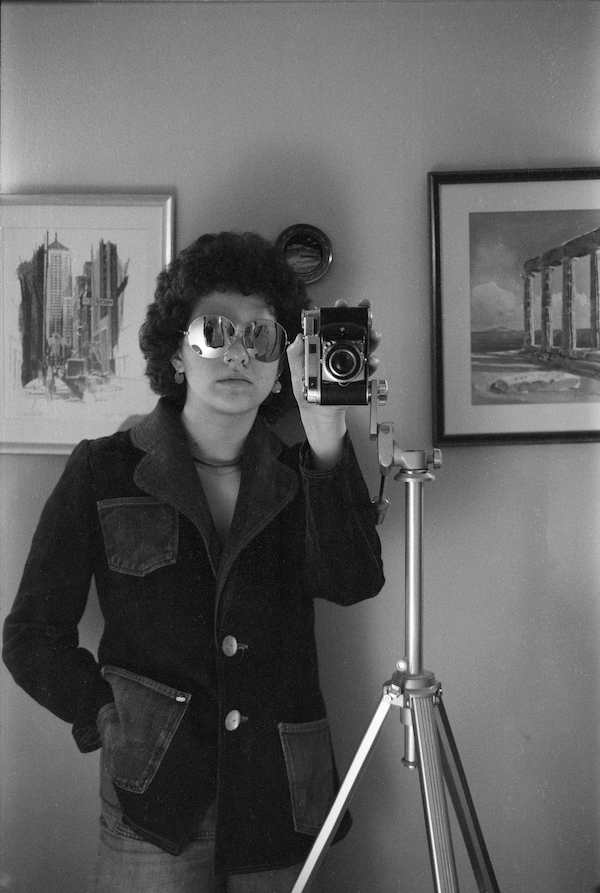

“Mylar Sunglasses, Cityscape” (1975)

Born and raised in Chicago, Greek American photographer Diane Alexander White has lived an urban existence that has refined her eye as a photographer. After receiving a Communications Design/Photography B.A. from The University of Illinois, Chicago, Diane served as a photographer at the Field Museum for40years. In addition to photographing natural history collections, Diane photographed a wide range of cultural life in Chicago (1970s-today), including parades and urban settings. The exhibit “Story Telling In Cloth and Light" (2023) collects photographs taken while backpacking through Greece in 1977.

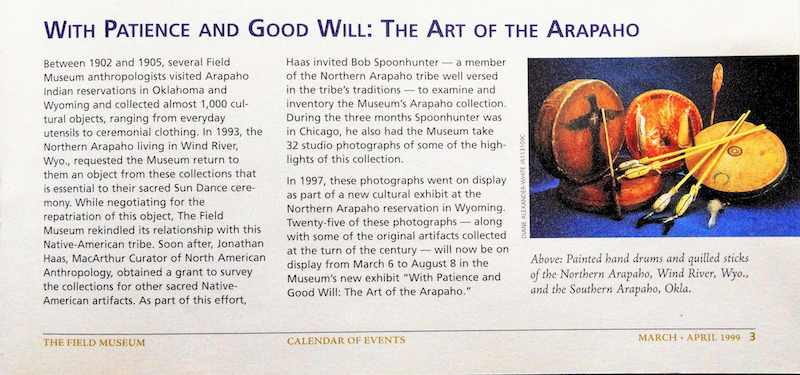

Diane created three photography exhibits showcasing the extensive Native American collection of artifacts. The exhibits called, “With Patience and Good Will: The Art of the Arapaho,” “Cheyenne Visions” and “Travels of the Crow: Journey of an Indian Nation," traveled to museums and tribal lands of the Plains Indians. Funding was granted by NAGPRA, The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

For over four decades, Diane has photographed Chicago’s community festivals and street parades. Her most recent exhibit, “Gather Together: Street Photography by Diane Alexander White” at the National Hellenic Museum, explores the role of community and connection in our lives through a selection of these photographs.

Interview (Questions by Yiorgos Anagnostou)

You are a Chicago-based artist and citizen. What does the city mean to you?

The City of Chicago has made me everything that I am in life and work. My maternal grandparents, Emanuel and Lillian Cotsones immigrated from Laconia to Chicago in 1913 and my father, Angelo D. Alexander, immigrated from Arcadia to Chicago in 1920. Both families left their Greek homeland for opportunities in America and to work in the family restaurant business which was a common theme among newcomers. Both families recorded the Greek-American experience with photo albums that I enjoyed as a young child and have shared with the generations that followed.

My curiosity with cameras came early in my childhood where I would ask my father, “can I take a photo with your camera?” Upon graduating high school, I was gifted a film camera that has recorded many of the images that can be seen in an exhibit called, “Gather Together: Street Photography by Diane Alexander White,” at the National Hellenic Museum in Chicago. While a student of photography at the University of Illinois, Chicago (UIC), our instructors encouraged us to photograph the Maxwell Street Market, Fulton Market, Greektown, Little Italy and neighborhoods that were within walking distance of the UIC campus. Those neighborhoods underwent a massive transformation with the construction of the expressways and UIC campus that split the neighborhoods in half and dispersed the immigrant populations to surrounding areas of the city and to the suburbs in the 1960s. My photos of Greektown in the 1970s records the remnants of businesses on Halsted Street that remained after the construction projects. Because the Greektown neighborhood is within walking distance to downtown it has undergone gentrification with the construction of condominiums, big box stores, Whole Foods, Starbucks, and marijuana dispensaries. My final graduation project in 1976 was to photograph Chicago’s 7th Gay Pride Parade that would become an important document to mark the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in 2019. Little did I realize that photographing Chicago as I knew in the 1970s and forward would create a record of an ever-changing city that contrasts with the present day.

Upon graduating in 1976, I entered the workforce as a photographer where I continued my passion for documenting the diverse neighborhoods in Chicago and elsewhere. In 1983 I was hired as a staff photographer for the Field Museum of Natural History where I photographed artifacts from around the world that include three traveling exhibits for the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Crow Nations. Looking back, it is obvious that the city that has informed my every decision whether professional or personal and continues to be a driving force in all aspects of my life. Will future generations continue to see Chicago as their muse?

What has the significance of Greek Chicago been in your life?

What followed for the Cotsones and Alexander families was the Great Depression and WWII. In the 1930s many people were on the brink of losing their savings because of the stock market crash in 1929. The Cotsones family pawned the family jewelry to pay the bills, the candy store was closed, nine-year old Chysanthe died of a burst appendicitis and papou [grandfather] died of a stroke in 1936 leaving a young widow with four children without the means for support. All of the children worked to make ends meet. The Alexander Restaurant was in a better position because it served a more affluent neighborhood in Hyde Park that included the University of Chicago. Both families were devoted to the Sts. Constantine & Helen Greek Orthodox Church in Chicago that served as a gathering place for worship, fellowship, that included the Koraes Greek Elementary School and Sunday school which strengthened relationships through the sacraments of baptism, marriage, and burial. Growing up Greek in Chicago meant gathering together for the holidays with my extended family to enjoy the food, card games and Greek dancing which can be seen in the family photo albums. My yiayia [granfmother] Ligeri Vournazou-Cotsones lived with us while I was a youngster and only spoke Greek in the household resulting in my understanding of the Greek language while I was a student at Koraes. As our extended family has grown, we continue to gather together to celebrate Easter with the lamb on the spit, tsoureki, red eggs, pastichio, spanakopita, kourambiedes, koulourakia and galactoboureko recipes from the family cookbook. We can only hope that the next generation can keep the momentum going as we pass the torch of Greek life as we know it from the generations before us.

What motivated your interest in photography? How would you place it in connection to your family, ethnic community, and Chicago’s broader culture and institutions?

My father, Angelo was a self-taught photographer who recorded photos with a manual camera and a handheld light meter. As a child I would accompany him to the drug store where we would pick up film and prints that can be seen in the family albums today. The photos are embedded in my childhood memory where I remember how the sun felt, the color of the clothing that I was wearing (even though the photos are in black and white) the furniture in our house and more. Because we lived in Chicago my parents took us to world class museums and filled our house with art and furniture that continues to inspire me today. For Christmas, my parents gave me watercolor paints and brushes where I would lose myself in a world of swirling colors and dream of becoming an artist. When I was accepted at UIC it was to follow in the footsteps of my cousin, Dean Alexander who became a well-known graphic designer in New York City. While studying graphic design I pursued photography where I learned how to process film and prints in the darkroom. My ever-present camera documented the world around me, and the photos continue to inspire people when seen in exhibits and shared through social media.

What were some of the opportunities and challenges for a woman artist pursuing professional photography in the 1970s? Where there any particular issues for a Greek American woman professional photographer?

Being a Greek American woman in the male dominated world of professional photography was not an impediment for me. Women’s liberation, civil rights, Gay liberation, and protests were reoccurring themes in the 1960s and forward. Also being a child of Spartan villagers gave me the θάρρος (courage) to pursue my destiny without question. Most Greek parents encouraged their children to become lawyers, doctors, and educators whereas my parents encouraged me to pursuing the arts. The guidance that I received from my father was to take classes in studio photography and lighting that would enable me to be gainfully employed. My first job out of school was for a photography studio where I used large format film camera, lighting, and darkroom skills. It truly paid off especially when I was hired as a staff photographer at the Field Museum photographing artifacts for scientific journals and art publications.

Has your heritage played a role in the angle you practice your art, the ways you are seeing your subject matter?

The Greek heritage has played an enormous role as a photographer because of my ability to approach people with positivity and honesty. We were taught by our parents and Greek teachers to be proud of our heritage and to pursue the best in ourselves in whatever we sought to do. Failure is not an option for a Greek child and that propelled me forward as an artist and in also raising my children. As a result, my children have become successful musicians in a band called, “White Mystery” where they have toured the world and celebrated their 15th anniversary in 2023. When they asked me whether they should be part-time or full-time musicians part time I told them, “full-time and don’t come back until you are famous!” The values that my Greek forebears instilled in me are honesty, love, family, honor, hard work, a sense of humor, setting goals, education and living a life of a Greek Orthodox Christian. Those values are imbedded in my children and will carry on for their children also. Recently my husband and I became the proud grandparents of Georgia Lillian White who is named for my mother and yiayia!

The photographs collected in the exhibit Gather Together: Chicago Street Photography were primarily taken in the 1970s and 1980s. They capture an important historical moment in the United States, the emergent public visibility of various ethnic and racial groups in parades, festivals, and neighborhood events. What were the circumstances that directed your attention to these events?

While a photography student at UIC one of my most influential instructors was Robert Steigler who sent us on an assignment to photograph the 1975 Bud Billiken Day Parade in the Bronzeville neighborhood on Chicago’s Southside. Looking back at those photos still captivates my imagination when I see them on the walls of “Gather Together: Street Photography by Diane Alexander White” at the National Hellenic Museum in 2023. In 1981 I photographed eighteen City of Chicago sponsored ethnic parades, cultural events and neighborhood festivals that have become the cornerstone of the exhibit. The parades took place in downtown where Chicago architecture, at the Daley Center and festivals in diverse neighborhoods throughout the city which included the Greek, Puerto Rican, Mexican, Italian, Black, German, Jewish, Irish, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Hopi Indian. The goal of the exhibit is to bring people together from all corners of Chicago where by looking at the photos they would see similarities rather than differences.

What was it that you were aiming at in this project?

When I was approached by the National Hellenic Museum to select the photos for the exhibit, I realized that would be a difficult task because of the sheer number of photographs in my collection. Fortunately, the curatorial staff was up to the task and made the selection of photos to create a cohesive exhibit. As visitors move through the exhibit often-times they see themselves or can identify someone that they know. At the end of the exhibit that visitors can enter the names of people who they recognize in a book that will create a document for future generations of historians.

I am interested in the affective dimension of this experience. How did it feel to be capturing those historical events?

As a street photographer I see the photo, aim the camera quickly and move on to the next subject which is possible in a public setting. Large scale events make it possible to photograph large groups of people or to focus on individuals as my eye catches them. People are gathering with their family and friends in a celebratory mood, and it is obvious in their expressions when you examine the photos in detail. The Kodak Retina Reflex 111c camera that captured the exhibit photos is on display at the museum because it was the catalyst that catapulted me into becoming a photographer. The photographic experience was a labor of love and not a project for publication purposes. There were very few women doing street photography in the 1970s and 1980s and in many ways I was able to approach people because of that.

Would you please share with us a couple of photographs from the exhibit and your reflections on what you see in them? Is there something that you would like us to notice?

Here are two photographs from the exhibit that I am excited to share with you. The first is a float from the Greek Independence Day Parade in 1980 that depicts the Caryatids who supported the Erechtheion at the Parthenon against the architecture of Marina Towers. On the float sponsored by the Achaia Claus wine company we see young men bearing the kylix and women with baskets of grapes while all are wearing togas. That is thousands of years of difference, right?

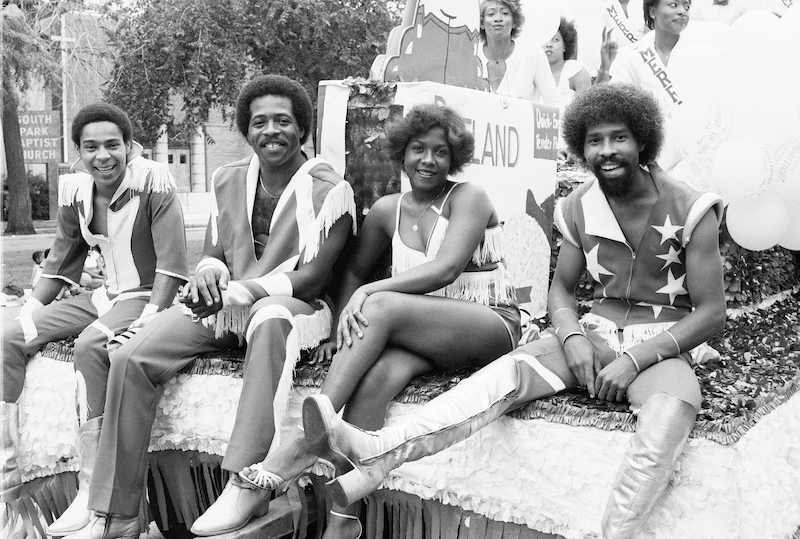

The next photo from the exhibit is from the Bud Billiken Day Parade in 1981 when disco, R&B, funk, and electronic music dominated the air waves and fashions worn by the people on the float that was sponsored by Riceland Rice. The men are wearing a natural Afro hairstyle while the women are copying the hair style of Farah Fawcett.

The first photo is a candid image whereas the second photo shows the subjects posing for the photo. The black and white images are not as distracting as a color photo. The viewer can pay closer attention to the details and composition of the photo.

In retrospect, do you ever wish you could have done something different as a photographer at the time?

There is nothing that I would have changed. The photos that have recorded are timeless and resonate with my audience today. In terms of a chosen career and pathway, photography has been a blessing. I learned a technical and esthetic skill that allowed me to make a living while raising three children with my husband of 40 years. Living in Chicago has allowed me to work for the Field Museum and other cultural institutions. Now that I am older, I can concentrate my efforts on scanning and sharing more photos on my website. (https://www.dawhitephotography.com/) The personal work has generated income because of licensing opportunities for films and books. The culmination has been the solo exhibit of my personal photography at the National Hellenic Museum.

You have a rich urban photography portfolio. You have been documenting the Gay Pride Parade Chicago for over thirty years (1976-2011) for example, and the Halsted CTA, Cabrini Greek & South Shore Streets (1974). You have also been documenting several Native American collections of artifacts. Would you please share with us a photograph from each of these three exhibits and reflect on their significance?

“With Patience and Good Will: The Art of the Arapaho,” at the Field Museum (1996), Photography by Diane Alexander White

When we passed in the hallway of the Field Museum in 1996, Bob Spoonhunter and I did not realize that we would begin a collaboration between the museum and the Arapaho called, “With Patience and Good Will: The Art of the Arapaho,” funded by The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Bob was the cultural advisor, and the photography studio became a place of creativity and respect for the living objects of the Arapaho. The exhibit photographed with a 4x5 film view camera and with dramatic lighting to highlight the colors and designs of the objects. The exhibit had a five-year run at the Field Museum with plans to travel to the reservation. On the day that he passed away of a heart attack in 1997, I received a large envelope in the mail with photos of a newly completed St. Stephen Church on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming with Bob’s stained glass and murals designs. Bob will continue to be missed by all for how he taught the way of the Arapaho.

“Cheyenne Visions,” at the Field Museum (2001), Photography by Diane Alexander White

The second collaboration between Native cultures and the Field Museum is called “Cheyenne Visions.” When Cheyenne Chief, Gordon Yellowman and his family visited the Field Museum to review the collection of Cheyenne artifacts in 2000 the idea was to give the artifacts life and breath for the next photography exhibit. Using a large format 4x5 view camera has its challenges because loading and unloading film takes place in the darkroom. The image has to be seen under a black cloth where it appears upside-down and backwards. Once the film has been removed from the film holder, Gamma Photo would pick up the box in the museum loading dock and delivered later in the day for reviewing purposes. The other challenge was dealing with the Cheyenne Elders who would decide what sacred objects not suitable for viewing. When completed, the exhibit opened in August 2000 with many of the artifacts that were photographed and seen by many of the visitors for the very first time. Looking back, it was as cataclysmic as Covid because 911 took place one month later. Life changed forever. The exhibit traveled to the El Reno Redlands Community College, Sam Noble Museum of Natural History in Oklahoma, and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Wyoming. My family traveled to opening on tribal lands where I received a Medicine Woman medallion that continues to inspire me to this day.

“Travels of the Crow, Journey of an Indian Nation Exhibit,” at the Field Museum (2007), Photography by Diane Alexander White

In 2007 I was approached by Helen Robbins who is the NAGPRA Specialist at the Field Museum to photograph artifacts for the last of the three exhibits. We worked with George and Edith Reed who were cultural advisors from the Crow Agency which is located at the headquarters of the Crow Indian Reservation the Bighorn Recreation Area and Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. We traveled to the sacred mountains and Yellowstone National Park where I photographed the landscapes that were added to the exhibit. We also visited the Reed Family and photographed them in regalia and interviewed George for the video screen in Travels of the Crow exhibit. The Crow are among the Plains Indian tribes in the Montana and Wyoming area where the hunted the bison (one chased me at Yellowstone while I running with video and camera equipment on tripods). The exhibit also and showed objects used for everyday living as well as religious and sacred items.

Currently you are “scanning film images from the 1970’s through 1990’s of neighborhood festivals and parades for future exhibits illustrating Chicago's rich cultures.” What is the significance of this project for you and the city?

This project would have had little, or no exposure had it not been for the internet. We live in an age of sharing our life stories through social media. In my case it is sharing a cache of photos that lived in a filing cabinet until film scanners and the internet made it possible to share on Facebook, Instagram, on www.dawhitephotography and other digital platforms. In each photo the moment in time has been frozen for time of day, weather, fashion, architecture, politics, skin color, and interactions during a street celebration. As the photos have gained traction online and in the exhibit people are discovering themselves which is a story in itself. The book at the end of the exhibit asks the viewer to enter the names of who they recognize. That is the ultimate take away!

July 18, 2023

Editor’s Note I: For an essay reflecting on “Gather Together: Street Photography by Diane Alexander White” see George Kouvaros’s “The Signatures of a Time and a Place in the World.”

Editor’s Note II: For archival purposes I share this question which was part of the initial questionnaire: You have stated your interest in mostly capturing similarities across various groups, not differences. Indeed, one of my vivid impressions after visiting “Gather Together: Street Photography” was the seeming similarity in the expression of heritage pride among various groups. Yet, from my perspective, these groups have had different histories and scales of stigmatization, exclusion, and poverty. I am interested in your thoughts regarding this tension between what we see as similarity in heritage celebration and the underlying differences in the placement of these groups within the socioeconomic order of the city.