Conversations with Dan Georgakas

(An interview series with Alexander Kitroeff and

Yiorgos Anagnostou)

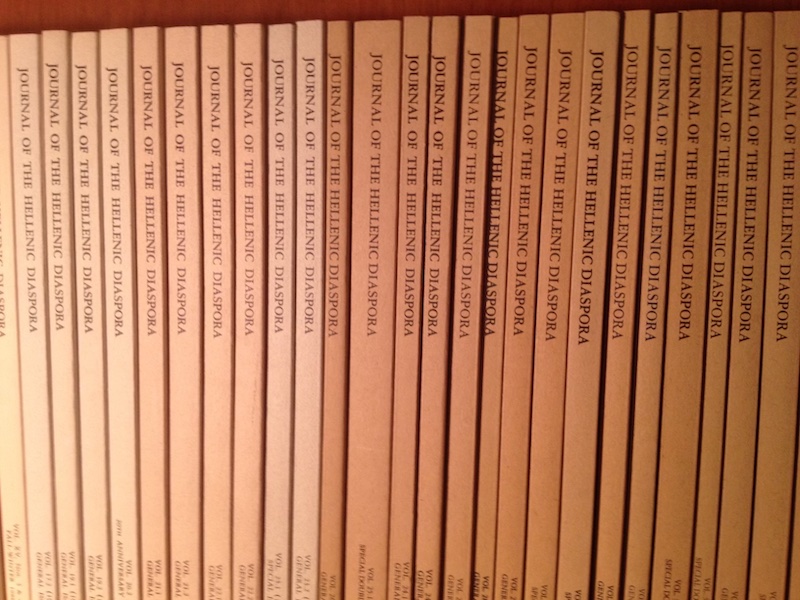

Topic: Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora

Interview questions by Yiorgos Anagnostou, March 2019.

Dan Georgakas (1938-2021) was a historian, film critic, author, educator, activist, editor, and columnist. His writing corpus includes an autobiography, My Detroit: Growing up Greek and American in Motor City and the much admired Detroit: I do Mind Dying: A Study in Urban Revolution (with Marvin Surkin). He coedited The Immigrant Left in the United States with Paul Buhle. Georgakas is noted for his editorial involvement with several journals, including Cineaste, The Journal of Modern Hellenism, and the American Journal of Contemporary Hellenic Issues. He served in the editorial team of the Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora over the span of almost forty years (1976-2013).

For the description of our joint interview project "Conversations with Dan Georgakas" see here.

Dan, you have been involved with many cultural magazines, including the Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora that closed shop recently. Would you give us a sense of the purpose of this journal? What was your own vision for the journal, some of the challenges, the contributions that you made and, also, the circumstances of its closing?

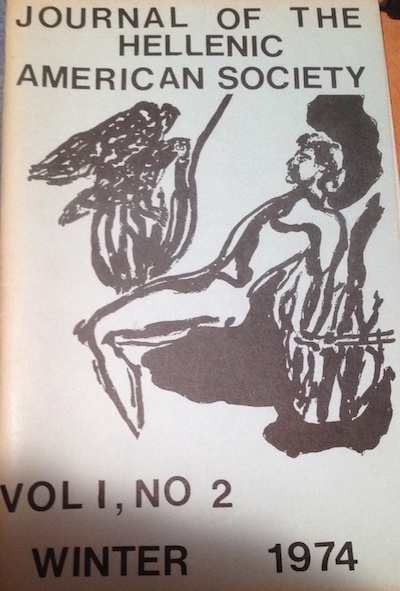

Well, the Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora (JHD) began in Terre Haute, Indiana. It didn’t have that name immediately, it was called the Journal of the Hellenic American Society (1973-1974), I believe, and Nick Petropoulos was the major mover of that magazine, and it was an antijunta group which wanted to figure out why was it Greek Americans were not responding the way we thought they might, and also [wanted] to respond, to be the response, which of course is what I always love from Detroit because of what I call the Detroit method. For instance, in Detroit the black poets—which there were quite a few—were just furious that the anthologies for the best poetry of the year never had blacks in, and they protested and this and that and Dudley Randall said, “the hell with it, let’s just publish it ourselves.” [And he created the pioneering publishing company] called Broadside Press (1965). And like City Lights in San Francisco, he made it small, cheap, and they sold tens of thousands of copies, and he eventually became the biggest publisher of Black poetry in the United States of America, because this librarian said, “stop with the protest and let’s do something.” So, [similarly], the journal in Terre Haute said we were going to do something, whatever it is, we’re going to do it. And so, they had articles protesting junta and thinking about it and all that kind of stuff. I wasn’t a founder, but I became [part of it], and I knew about [these issues] because I was in the antijunta movement, and I wrote for them and tried to help them and all that kind of stuff.

[Editor’s Note: In July 1974, the Journal of the Hellenic American Society was renamed Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora: Critical Thought on Modern Greece, and a year later Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora: Critical Thought on Greece and World Issues. It took its name Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora in Winter 1978. Dan Georgakas is listed as a member of the team of coordinating editors in April 1976.]

I remember also they were calling for solidarity between Greek Americans and people of color.

Oh yes. Oh yeah. It was very progressive, politically on the left. I mean [inaudible] they just had those positions called social democracy, fine, but [inaudible] they were for the black revolution. Yeah, that’s me. And then when junta fell, Nick decided he’d go back to Greece. And so, he wrote to me, he said, “I’d like you to continue the journal in New York.” I was astounded, I said, “why me?” I mean I wasn’t that intimate with them, and what good qualities do I have? He liked my point of view, so that’s why I said they were on the left and he knew I was involved with Cineaste, so I knew about publishing, and he also knew that I had relations with Peter Pappas and Alex Kitroeff and some other people, and he thought we were the kind of people that could continue the journal. So, I’d already met Leandros [Papathanasiou] from Pella [Publishers], and I approached him, and I said you know they want us to do this magazine and so forth. Leandros was a printer [and he agreed], and we put together an editorial team. First question which came up interestingly enough was changing the name because Journal of Hellenic Diaspora [did not sound] scholarly enough. And me of all people said, “I think this is what makes it,” [“we are the diaspora, and we are not just going to write about Greek America”*], but will [also] talk about Greek Canadians, Greek Australians, etc. And so, some of the more academic people said okay, they went along with it, and the idea was the journal would publish only scholarly, valid articles, but there would be to the left as much as possible, [though] some topics weren’t; but [“the idea was that this journal would be open to all political points of view, as long as it was presented in a scholarly fashion”*]. But [leaning to the left] as much as possible and would also explore unexplored territory in Greek America. And I liked that. [inaudible] A peer review journal has its virtues, but one of the things that makes peer review journals less interesting is that they haven’t got a personality necessarily. So, this journal (JHD) is going to have personality—not to say individual personality but a group personality—and it would wax and wane in terms of where it went. I mean cantankerous. Really wanted to go in new directions whenever possible, cover stuff we hadn’t covered. And some of the academic articles that came into the lab, ok., but they’d been published in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies. But that’s ok, as long as I could do what I wanted to do within this context, that’s where that anarchic mentality helps, not everybody had to agree with it. So, if we came across a document that had not circulated [previously], that was important, [we would] print the damn document, the whole document; it’s not a scholarly article, we don’t have popular audience here anyhow. But that article could be drawn upon by many people, so if it’s the OSS report of Greek Americans or if it’s a dispatch from Athens to Washington in 1948, well let’s print it. Somebody may really find it very useful, and more or less we agreed and went along with it. We published a Works Progress Administration (WPA) material which had never been published before; and we were not interested, for the most part, in academic titles so if you were a graduate student or not a student, and you wrote something of value, we publish it, we didn’t care. [The author] didn’t have to have an academic background. Most did, you know. [“Sometimes it was hard to get scholars, reputable scholars because […], they couldn’t use it for their tenure track. But we published a lot of stuff, in retrospect. Wow. Nobody else published this stuff. And it’s going to be useful, and a lot of these documents we published will be, I think, perennially useful. For instance, if we publish the letter from the State Department in 1947 or 1948, regarding the Greek Civil War, it may not in and of itself a smoking gun or anything like that—but there it is. That’s what they (the State Department]) were saying. Well 50 years, 100 years or so, someone wants to know what the State Department said, well there it is.”*]

So, through those 40 years I was practically handling every job on the magazine, at some point that book review editor, circulation, etc. And sometimes […] [when] I couldn’t do it for a while, I would drop out for six months or a year or just send letters and talk to people, but I stayed with the project. We also [collaborated?] with Leandros [to create?] Pella Publishing. We published books and he asked me and others, “should I publish this one?” […] Sometimes we said no don’t publish that one, and I’ll do this anthology, but leave out both essays, so it was an ongoing enterprise. Very poor reception.

By the community?

Very little community. And then Leandros, a wonderful, wonderful man, he’s a very good printer, fabulous—his typesetter was a copy editor, “Hey, you got that word, you got that spelled wrong, that’s the wrong Greek word,” you know is the typesetter when they were doing it—hard type, but he [Leandros] was not good at maintaining the subscriptions, outreach. I tried many times to work with him on this, and I guess I admire him so much but I’m just being candid because people say, “what happened?’ For instance, early on we had an offer from, I forget who it was from, to join a major […], one of the first online services to bring the journal online and have people subscribe, and I had it all set up and [he] didn’t follow through on it—didn’t even follow through on it. Sometimes we get somebody [wanting to] sell their books [to Pella Publishing], and [he would not take the offer, he would object saying] “I don’t like their politics, or I don’t like that, so don’t let them sell me more books.” I said, “when people buy the book, they’re not buying the distributor’s reputation, they’re buying the book,”—so he wasn’t good at those things, but he did not interfere with the magazine or interfered only in the correct way into naming suggestions—“could we do that, or I don’t like that” and so forth and didn't insist—wonderful, wonderful. Kept doing the magazine, and basically it broke even for a long time. Then slowly costs went up etc. I suppose in a long, long, long run it broke even. I say that [inaudible] because like how do you keep a journal going you know without paying anybody. The journal itself; so he was producing a journal at cost, plus postage; and [the postal rate just skyrocketed], sending some overseas became very, very expensive so we lost a lot of subscribers, they couldn’t afford the postage because postage cost more than the magazine [inaudible]. At any rate, we went on for 40 years and then Leandros decided he was going to retire, and his son who inherited the business [and] liked the journal, said, “but I can’t afford it, and I don’t have the passion my father has for this thing,” and so that’s why it folded. (see here.) And I was one of the founding editors now. [inaudible] and the magazine was in demise. I think we did some outstanding stuff through the years, something I’m impressed. Oh my God, oh yeah! We publish that and we did some innovative things for instance: we do have one issue which is on Greek film written entirely by Greek critics, so nobody else did that, nobody else did that. We did a lot of stuff on Greek America, and we didn’t shy away from political stuff. So, I think it was a pretty successful venture, and there’s not too many independent publications they went for 40 years, and people respected us when we went out; they respected us a little bit when we went in, they respected us more when we went out. Pretty good. What’s a scholar to do? That’s one of the things scholars do and it’s there, it’s there, it’s there. And of course, I wrote this long piece on the Greek American left which is the only piece in English which covers that time period, basically from the 1900s to about 1960.

I have a couple of questions. One is whether you tried to do some fund raising. The other is about two words you mentioned, two key political words. One was public scholarship from a leftist perspective, the other word was anarchic. Could you elaborate, people sometimes are not clear of what these terms mean.

Saying you’re an anarchist it’s very odd because people don’t know what that means. Does that mean you want to throw bombs? Does that mean you have a black mask on your face? What does it mean? Well, it means many things. So, this is what it means to me. There is socialism which means that the community will control the means of production for [the] community, universal community development for individual development. Ok. So, I’m a socialist in that sense, but one of the great problems of socialism is that many people who are socialists are very authoritarian. They believe the vanguard party should tell people what to do etc. The anarchist tradition is to be ultrademocratic to maximize individual freedom within the socialist system, and in that sense Peter Kropotkin did the most work in imagining a society like that, and so that’s my vision of the future. I’ll give a good example. Right now, we have automation. And people say, “gee that gets people lose their jobs.” As an anarchist I can say good, I don’t want to work, I don’t live to work. Can we take the profits and instead of getting the three, four people become billionaires, let’s distribute those profits; cut the workday to four hours a week, four hours a day, maybe less. One anarchist […] said, “a full day’s pay for a full day’s play.” Well, that’s poetic, but with that idea we’re not here to work, and we’re bound together as a collective to help each other because that’s actually smarter than competing with one another.

Based on this context would you please elaborate how did your perspective of anarchism play out in your role as an editor? So, how does a person who subscribes to this ideology, how does this inform his decisions and vision as an editor of a journal?

One, this person opens the journal up in terms of like no one is excluded because of their thoughts. When people are being excluded because of the quality of their thought, or the argumentation they make of the documentation, but not because their orientation. And I have many conservative friends and [they say] “you’re my favorite leftist,” and so on. Okay, because I say, well, if this person is an honest person and they’re following logical lines and accept facts maybe I could be wrong about something. Or maybe I can learn from them. Or maybe they’ll see that I’m right because of my logic so why should I disparage them as a hopeless right winger. Aris Karatzas—I call him my favorite monarchist and we used to go back and forth all the time—but actually, as time went on, we found many things that we actually agreed on. So, I’d bring that perspective as an editor [inaudible]. It’s almost like, “I don’t want to know who wrote it and I don’t want know what school they went to and then let’s see what they have to say.” So, that’s one thing. Second thing is, why not publish a dissenting view to your view if it’s substantive in some way? And I guess that maybe that simplifies it, but it makes a difference because most editors are very subjective anyhow and can be very authoritarian. I would say the main thing about anarchism, or the anarchist thing, is we’re antiauthoritarian, whatever the authority, whether it’s a political party, a church, anybody with a dogma that tells me I got to accept a dogma on faith. Well, that’s not scholarship, that’s something else.

Were there any debates with the editorial team about publishing heavily theoretical work? I know this is an issue in Greek American studies in general. Some researchers are suspicious perhaps, or reluctant, or impatient with theoretical work. How did this play out in the journal?

It really didn’t play out that much because we always were looking for enough good articles to make a decent issue, so if it was theoretical, it was theoretical; and if it wasn’t theoretical, it wasn’t theoretical. Now personally I try to look for and stimulate and find people who write like I do. [inaudible]. It’s just I’m not necessarily interested in that, or I’m mildly interested in that sort of thing [theoretical work]. I don’t remember any articles being rejected because it was theory.

Was that an issue in choosing the books that the journal would review? Because, in all due respect, just to mention an example, Ioanna Laliotou’s book Transatlantic Subjects. I mean, here we have a serious book written in a theoretical way and it doesn’t appear [reviewed] in the journal …

[Editor’s note: Dan reviewed this book for The Journal of American History, 92.2 (September 2025): 637–38.]

First-of-all, it was not deliberate. [It was] like, “oh God we missed that one” or we didn’t see anybody volunteering to do it, and therefore we didn’t think of it ourselves for whatever reason, and so you have that problem, and that’s one of the good examples of the other kind of journal, or the peer reviewed journals not gonna let that happen. Whereas in ours, because of our style, that could happen. But it was never deliberate. I can’t think of any piece that we didn’t want to review because we didn’t like its point of view.

Sure. Is there any advice you would like to give to a person who’d like to start a journal on Greek American issues?

Get a big bottle of aspirin [laughs]. Be prepared for people say, “great,” and not give you any money. You must have the personal passion and [also] have a practical part in your thinking. My feeling is if you publish something and can’t get enough people to support you, you’re doing something wrong. So, you should have enough money or thoughts how you’re going to survive the first year or two because after a year or two, then if you haven’t attracted some kind of response, then what are you doing? What are you doing? When we published Cineaste we subsidized it to begin with, but the idea was always that if “I can’t get a couple of thousand New Yorkers to subscribe or buy this magazine I’m not saying anything.” Well, that one is now in its 15th year and has its subscribers, has its advertisers, it gets its grants, etc.

If a prospective editor of this generation needs a huge bottle of aspirin what should his or her motivation be to undertake this kind of project?

That’s a good question. It’s almost an irrational passion. And it could be, you know, you see these more literary magazines where someone is a poet and they like a certain kind of poetry, so they’re going to have a magazine advancing this line of poetry or their own line of poetry, and I think the same is true [and it becomes] more and more complicated in putting out a journal of any kind. I think you have to have passion, and you have to say to yourself who do I want to read this journal. And that does not mean writing down, or altering, it just means thinking about who this audience that you want to reach is, and that’s tough. That’s very tough.

So, you mentioned that as an editor you need to think about your audience and let’s say if your intended audience is the cultural leaders of Greek America, what are some of the issues that we should be paying attention in trying to reach out to this audience?

I think the major issue of the day, of the future, is how do multiethnic children of Greek Americans decide to be a Hellene. Now, all the major organizations should be concerned with that issue. So, you have articles about that, you might have theoretical articles, or might have factual articles, you might even have poetry, and then you’ve got to bring it to their attention. You really do. And you never know who’s going to respond. You never know. You say, “they’ll never respond” and the people will respond; and you say, “for sure they will” and they don’t.

And if you would like to reach out to the broader Greek American public?

Well, I think that’s very difficult because there are no secular organizations other than the fraternal organizations, I put quotation marks around “fraternal.” So, unless you get them backing you—in other words, AHEPA has a lot of money. AHEPA has fulfilled its destiny. It really has. It wanted to have a Greek America that was very acceptable and popular [inedible] and it wanted to project, correctly or incorrectly, that the Greek Americans are connected to the classics. I think they are correct in the broad sense, not the genetic direct line sense, and they’ve done that, and they’ve got lots of money. So, if they support a magazine, they can bring somebody in and give him a thousand dollars to give a speech, you know, and give some real support to these [cultural] organizations. They go golfing, they spend lots of money on golf trips and they have big banquets and so forth. And I’m not criticizing AHEPA per se, I’m just using them as an example, and there are other smaller organizations who could say “let’s help this journal,” but they seem to think that somebody else will take care of this.

Published on March 03, 2025

Editor’s note: Citations marked by an asterisk are taken from other segments of the interview referring to the Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora.