Lindsay Hand: Bringing Ludlow to Life

It was while working as a waitress in Colorado Springs, Colorado, when Lindsay Hand began engaging with labor issues in her art. A commission by a customer—a worker’s compensation lawyer—for an oil painting in memorial of the Ludlow Massacre marked a monumental moment for Lindsay, sparking a reorientation in the ways she practiced and attached meaning to her art. She began researching the history of the massacre, a subject she knew nothing about, delving into the archive and reading books about the event. A visit to the Ludlow Massacre Memorial further enhanced her political and affective connections with that past. The drive to tell the story grew, decisively directing her view of art as a socially engaged practice.

A worker in the service industry when she first “encountered” Ludlow, Lindsay recalls in disbelief how she, a Colorado native, living in a city only 115 miles north from the site of the massacre, was oblivious to an event of such importance for worker’s rights. A veil of silence blanketed the topic, both in her high school and the culture around her.

“Did you consider yourself politicized before you turned to Ludlow?” we asked her. “Yes and no,” she replied. “Raised in a very conservative family,” Lindsay “intuitively walked away on the other side,” entering the “more liberal” world of art, eventually “becoming pro-union.” Her life’s circumstances animated a political consciousness in her person, shaping her decision to portray that which has been marginalized, even forgotten.

Lindsay’s decision to embark on visual representations of the Ludlow Massacre was far from immediate. Operating within the gallery world at the time, she experienced signs of discouragement—“no one wants to buy paintings about a massacre,” she was told. But she insisted on taking a great financial risk in devoting herself to a topic others were ignorant of or ignored. A taboo topic turned into the centerpiece of her engaged—and engaging—art.

Opening Exhibit / April, 2014

The Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum

Photo Credit: Angel Bellardinelli

Moving outside the traditional gallery scene, Lindsay found hospitable spaces in museums and cultural entities committed to preserving and displaying the history of the labor movement. Her series of paintings Remembering the Ludlow Massacre was exhibited at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum in April 2014. It was part of a collaborative installation with historical artifacts and writings by Curator of History Leah Davis Withrow and gallery designer Kelly Murphy. The City of Trinidad purchased the series, eventually finding its permanent home at Trinidad’s Southern Colorado Coal Miners Museum. Her various portrayals of the legendary labor activist Mother Jones are on display at the Irish American Heritage Center in Chicago (We Shall Fight Until We Win), Embassy of Ireland, Washington, D.C., and the Mother Jones Museum in Saint Louis, Missouri (We Want Freedom). Her visual interpretation of murdered labor activist Fannie Mooney Sellins—a portrait bringing the spirit of this martyr to life—is currently displayed at the St. Louis Public Library.

Exhibited during a state-wide commemoration of the Ludlow Centenary in Colorado, Lindsay’s Ludlow Massacre series pays tribute to the strikers and their families who fought corporate exploitation and died defending their rights. Lindsay relates that she consciously refrains from sensationalizing the bodies of murdered laborers and labor leaders. Although she labors to portray their often misconfigured and savagely beaten bodies, this corpus remains private. She wishes these images to remain outside the public gaze out of respect, preferring, instead, that the public remembers these individuals in their dignified humanity.

Oil / 40” x 72”

During her initial exploration of the Ludlow Massacre, the tragic death of nine children and two women—burned due to the soldiers setting the tent colony on fire—was particularly shocking to Lindsay. As a person and a mother, she relates profoundly to the pain associated with the loss of a child. And although the churned bodies are absent in the portraits, the figures of the dead are still present in the exhibit symbolically. Her project consists of a life-size series of eleven oil paintings, one for each of the women and children who found their grisly death in the scorched tent colony.

In interviews, Lindsay has spoken about the perspective directing her visual renderings and the relationship she cultivated with the subjects she brought into representation: “The individual participant’s purpose and fortitude became the perspective from which I decided to approach the paintings,” she says. “I sought to feature the strength and resilience of the women and men, the spark and innocence of the children, and the unity of the miners in Southern Colorado. … They became very real to me: the people of Ludlow.” Ludlow is not about an abstract loss of human life; it involves real people whose realness Lindsay felt and seeks to communicate through her art.

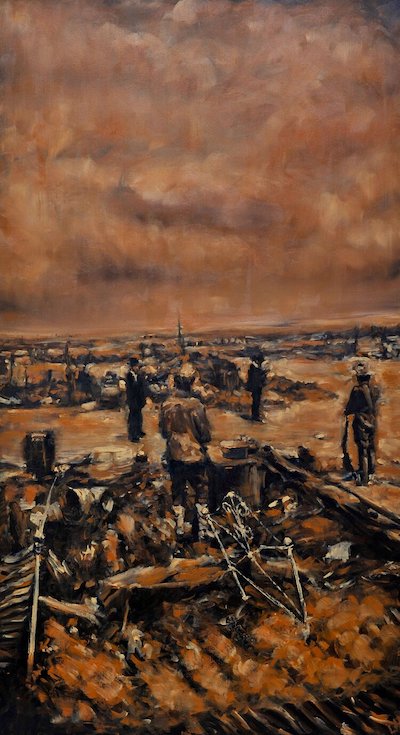

Oil / 96” x 72”

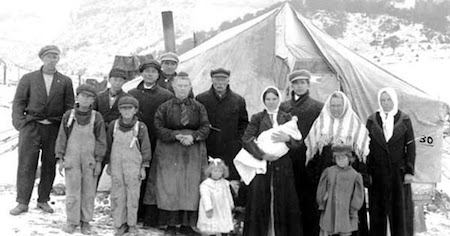

Lindsay’s visual tribute to Ludlow reinterprets in color a graphic archival source, the black-and-white photographs taken throughout the strike and its aftermath. Furnishing documentary evidence, these images were of paramount political importance for the Union. Leaders of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) started the systematic collection of photographs as early as 1914. Adding their captions and commentaries onto these visual documents, they utilized the images in the subsequent battle of symbols and words over the meaning of the violent clash. Ultimately, the Union succeeded in establishing the event as a Massacre against those denying this characterization, casting it, instead, the “so-called” Massacre.

Lindsay’s renderings then add yet another layer to the history of Ludlow’s representations from a working-class perspective. Her aim, indeed, to foreground “the unity of the miners in Southern Colorado” dovetails with the Union’s major preoccupation at the time to instill working-class togetherness across the plethora of nationalities among the strikers. Her centenary exhibit foregrounds the strikers’ communal unity, sociability across ethnic lives, the importance of immigrant labor leaders such as Louis Tikas, defiance, the “Death Special” armored car firing bullets randomly on the colony, killing and maiming bodies, the ghastly image of the burned tent colony. Her work contributes in color to the palimpsest of the Union’s memory narrative.

Oil / 84” x 72”

How did Lindsay feel about the people she portrayed? How does she envision her work speaking to audiences? In our conversation, she speaks about her emotional involvement with the project, connecting her own feelings with the work’s relatability with the audience.

“I dove in to express my feelings,” she tells us, “I had to dig deeper into photos that were more subtle. [I sought to] personalize it, bring the element of energetic interaction that a viewer may not have from a photograph.”

Indeed, the expressionist brushstrokes convey a sense of movement across the static, black and white figures captured still in the photographs. The colors animate the characters from the past, bringing their figures closer to the present and nearer to us. The impact of the realness of the strikers, Lindsay envisions, will generate concern among viewers about what they see and how they see it. Concrete lives lost for a just cause.

Lindsay’s colors contribute to keeping the memory of the Ludlow Massacre alive. They animate this past, bringing at the center of our attention today human beings who fought for justice and dignity and paid a great price for it. They wave at us through Lindsay’s brushstrokes, calling on us, “Look at me and see there’s a story to be told. Remember what happened here; it’s part of your history.”

Yiorgos Anagnostou teaches in the Modern Greek Program at the Ohio State University.