The Anarchist and the Saint

When Yiannis Gigas Thomas opened the door to his stone house in Epirus, I gave a cry of surprise. I had expected a monk since only an ascetic would devote himself to painting icons in self-imposed isolation. But rather than a holy man, he identified himself as “an anarchist, Orthodox Christian, and Greek patriot.” After this provocative introduction, I realized I was standing in front of someone original.

I had waited for years to meet Gigas, ever since Yiorgos Anagnostou and I began our research project on Louis Tikas (1884-1914), the Cretan immigrant, who led the great coal strike in Ludlow, Colorado. He and twenty strikers and members of their families were killed in 1914 by the Colorado National Guard and the militia of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company in what has become known as the Colorado Coalfield War. Learning that Gigas commemorated Tikas with religious icons, I asked him for an interview. He invited me to his remote village in Epirus.

I did not know how isolated this place was until I tried to find it in May of 2025, driving with my daughter, Clare, and her partner, Lincoln, who took the wheel. Thanks to Lincoln’s steady nerves, even when our GPS gave up, we managed the switch-back roads over the mountain passes and treacherous trails. After four hours of dizzying curves and turns, we arrived, and I spotted Gigas’ cottage by the white awning and the cow scull lodged on his stone fence. “Our house has an aesthetic quirkiness,” he had warned me.

Gigas greeted us all with a bear-hug and a kiss on each check and invited us to sit down in the coolness of his “quirky” courtyard. As soon as I took my seat in front of boxes of seedlings, I opened with the question I had been holding all these years: “How is it that you, living in this out-of-the-way place, came to create icons of revolutionary figures like Louis Tikas and Mother Jones?” His unexpected response wended through Greek art history, Orthodoxy, American labor relations, aesthetic theory, family trauma, and personal illness.

Born in Athens to a working-class family, Gigas went to the School of Fine Arts where he met his future wife, Peggy. After getting their degrees, they distanced themselves from western art and tried to form an artistic commune with like-minded artists in Gigas’s ancestral village. While this community never worked out, he and Peggy bought the village’s former general store and converted it into an artist workshop.

At first, they made a living as hagiographers. To show us examples of this early work, Gigas drove us to a small, 18th church, “Ayia Kyriaki” in the forest that he and Peggy had been commissioned to paint. When we stepped in, we were amazed by the results of their two-year labor of dedication and self-sacrifice. For they had covered all the surfaces, including the ceiling, with religious iconography.

Since this traditional work did not satisfy his restless spirit, Gigas began to look for alternative subject matter and methods of painting. This led him to Tikas. He had read an article on this Cretan immigrant in a provincial newspaper and then traveled to the United States with his sister, the journalist Lambrini Thoma, who was working on a documentary on Tikas. Because of artistic and ideological differences, though, Gigas withdrew from the project and the two siblings have not spoken since.

I asked what drove him to portray Tikas as an Orthodox saint since he was usually regarded as a secular labor leader. Indeed, organizations like the United Mine Workers of America honor him as a fighter and martyr. Some Greek Americans celebrate him as a national hero and have erected a statue of him in Trinidad, Colorado. Others dismiss him as a rabble-rouser. David Mason has composed a long, narrative poem about him. And he appears in Tony Garcia’s play, “Ludlow: El Grito de las Minas.” When the Bishop of Denver commissioned a series of panels on the ceiling of the Offices of the Metropolis telling the story of the Greeks in the West, he asked that one panel depict Tikas and the Ludlow Massacre. In all these portraits Tikas is a man fighting for workers’ right.

Gigas, on the other hand, shocks in his seemingly sacrilegious apotheosis of the strike organizer. He turns Tikas into a saint who held Christ as his “model” and who expressed the authentic spirit of Christianity. Gigas cites approvingly the words of the Eugene V. Debs, the American trade unionist, who wrote in 1915 that “Tikas made Ludlow holy as Jesus Christ made Calvary.”

In his most famous work, “Resurrectional Ethnogenesis at Ludlow,” which was first exhibited in Athens in 2014, Gigas sets Tikas in a complex narrative. Using the techniques he learned in the School of Fine Arts and during his long years as iconographer, he gives the story a social and political momentum.

Tikas, dressed in a dark blue suit, is suspended in the middle of the canvass holding a child in his left hand and reaching out benevolently to the workers in Ludlow. The text identifies him as the “Killer of Death,” a clear reference to Christ who “trampled upon death” in the Orthodox hymn of the Resurrection. Below him, the late British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher and enemy of workers, and John D. Rockefeller Jr., the owner of the mine company, are portrayed as Hades. Just above Tikas are the miners and to his right and left stand the great fighters for the oppressed: Mother Jones, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lawson (Tikas’s fellow union organizer), Spyros Kayalis (a revolutionary in the Cretan revolts of 1895-1898), Red Cloud (the Oglala Lakota chief who fought against the US army efforts in the 1860’s to build the Bozeman trail through Lakota territory), Big Bill Haywood (a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World) and Saint Basil the Great (who, in the words of Gigas, “gave revolutionary addresses against wealth”). Inscribed over all of them and framed by two angels are lines from Matthew 5 “Blessed are the poor.”

When I asked Gigas what he meant by “ethnogenesis,” he said he had in mind a nation built on the principles of “justice and freedom” which the multi-ethnic workers of Ludlow had fought for in 1914, a nation illuminated by the spirit of Orthodoxy.

Fascinated all my life by how art functions in different historical eras and geographical locations, I noted how Gigas’s icon, rather than inviting disinterested contemplation from its viewers, assaults them with its mixture of the sacred and the profane. This melding of religious imagery and references to class struggle keeps Gigas from sanctifying Tikas, from turning him into an apolitical hero. For Gigas, Tikas expresses Christ’s struggle for the poor and the disadvantaged. In a sense, Tikas helps Gigas politicize Christianity and Christianity aids him in sanctifying Tikas.

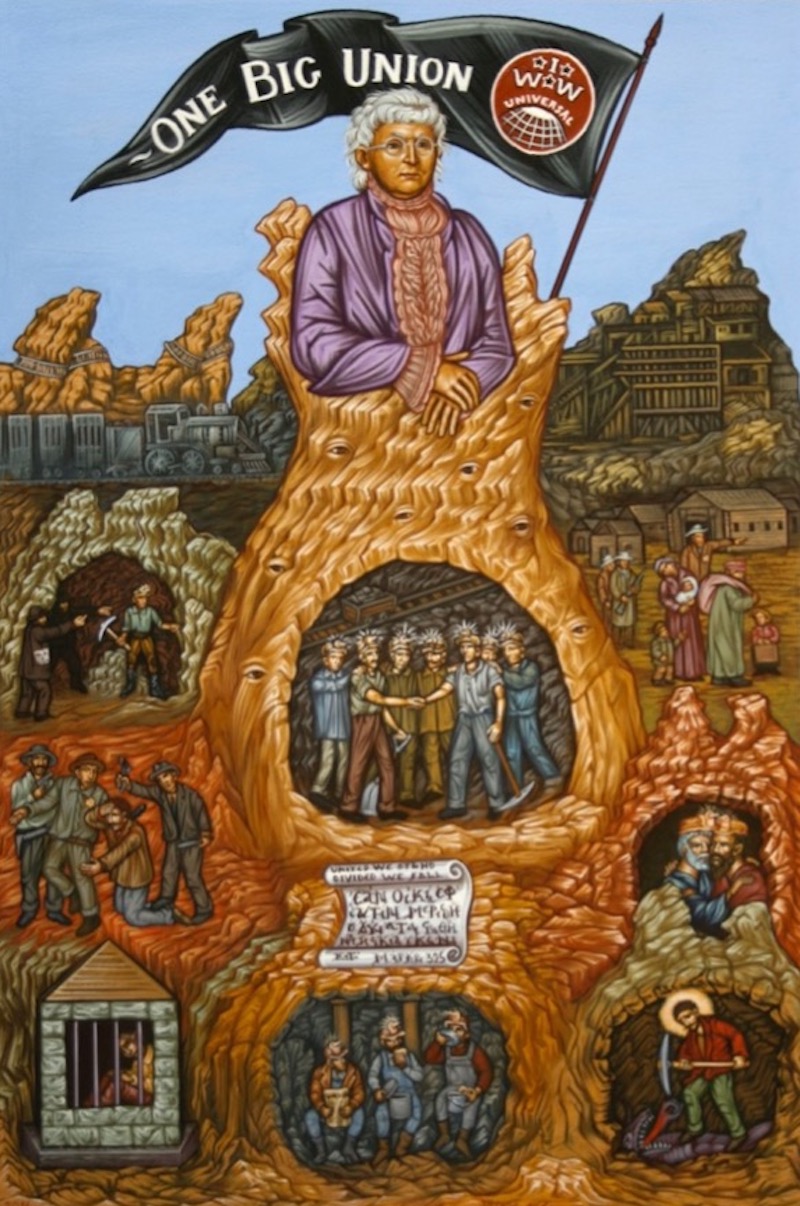

Gigas emphasizes the exploitation of workers and the fight for justice in related paintings such as the one showing the frightened migrants huddling in the hold of the ocean liner “Patris.” Another portrays the mangled bodies of workers killed in a mining accident, and one called “One Big Union,” depicts Mother Jones superimposed over scenes of miners and their families. Hard to place and define, these works draw from Gigas’s technical training and complex blend of aesthetic and political ideologies.

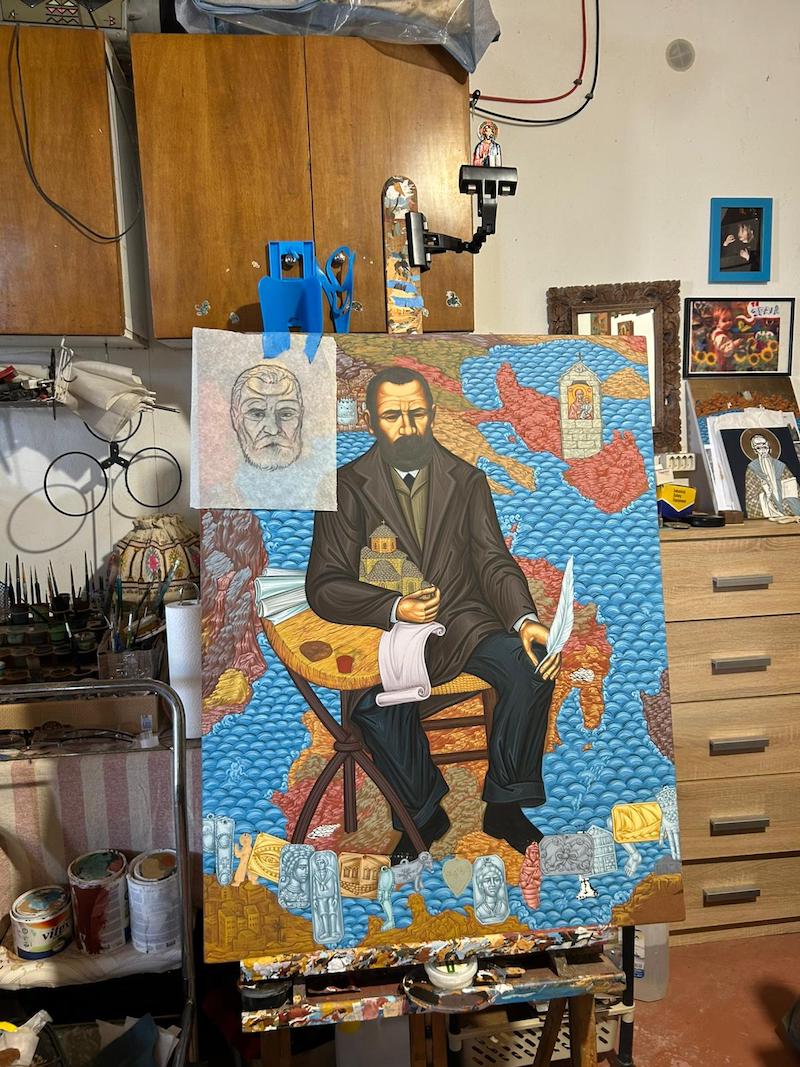

When I asked Gigas what he was working on currently, he led us to his work-in-progress, a commissioned work on Alexandros Papadiamandis (1851-1911), the author of the disturbing novella, The Murderess, which in a way stems from Euripides’ “Medea” and which anticipates Toni Morrison’s Beloved. The painting portrays Papadiamandis as a towering presence in Greek history; like a Church-Father, he sits over a map of Greece with a chapel in his lap, surrounded by historical personages and important geographical landmarks. Gigas said that Papadiamantis tried to “express the struggle of Greece” for national dignity, universal justice, and respect for the down-trodden and forgotten. He said that he strived to portray similar ideas in his paintings.

Not trapped in the past, Gigas is ready to evolve his art forms. He plans to use comics to convey his message of hope and justice to young people and to bring attention to the lives of the less fortunate. He spoke glowingly of manga, the Japanese genre of comic books and graphic novels. Refusing to enter the institution of teaching, he and Peggy are looking for alternative ways of addressing current audiences.

As he explained his theories and techniques, I thought how he and Peggy could have had brilliant careers in Athens, had they chosen to work within established institutions and protocols. Instead, they have stayed true to their ideals and make a living by their commissions and from the land.

It’s a challenging balance to pull off. The Orthodox Christian creates a painting called “ethnogenesis,” the birth of a nation on American soil and the construction of a just social order. The anarchist aligns himself with a labor organizer and systems builder. And the patriot sanctifies a hero of the Hellenic diaspora. Gigas’s work becomes more powerful because of his refusal to conciliate between these struggles within himself and his work.

When we returned to the courtyard, we found the feast Peggy had prepared for us: home-made bread, pita with wild greens, sauteed meat, peppers stuffed with local cheese, fried potatoes, salad, and other specialties. Clare and Lincoln seemed overwhelmed by the unexpected offerings.

Gigas invited us to spend the night. But I declined politely, not wishing to impose upon them any further. As we left, Peggy gave us a parting gift of tahini cake. Gigas wanted one last picture with his right arm raised in defiance.

As we were pulling away, I began to think about the purpose of my trip to this distant village. I had arrived with the intention of interviewing Gigas about his depictions of Tikas. But my research journey was ending with questions about how I understood this revolutionary Greek American. Each person, it seems, created his own Tikas. On the drive to the main road, the figures of Tikas and Gigas seemed to get smaller in our rear-view mirror. The immigrant who was killed in Colorado was acquiring a halo next to the anarchist. In the honey light of the afternoon, Gigas showed that Tikas still lived.

Gregory Jusdanis

July 20, 2025

Gregory Jusdanis teaches Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at Ohio State. His biography of the Greek poet C. P. Cavafy, co-written with Peter Jeffreys, will be coming out this August with Farrar Straus and Giroux.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to Yiannis Gigas Thomas for giving us permission to use photographs of his work.