Voice and Voicing in Blessings and Vows: “Finding” and Funding Heritage in the Greek Transnational Village1

by Yiorgos Anagnostou

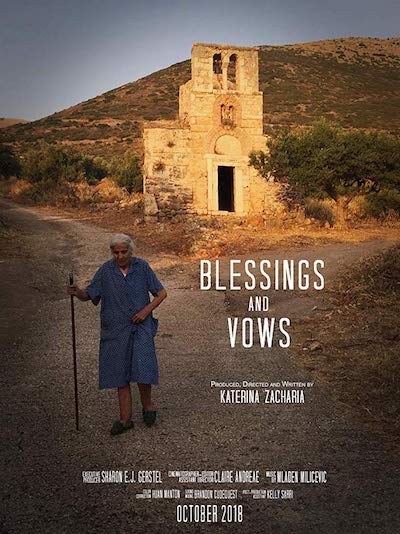

Blessings and Vows (2018) is a documentary about the current physical state and significance of a precious heritage monument, the eleventh-century Byzantine church of Hagioi Thedoroi in the village of Vamvaka on the Mani peninsula. This is a short yet multifaceted film, whose scope, focus, and narrative voice set to accomplish two purposes, namely to fundraise for the preservation of the monument and to document the monument’s relationship to its stakeholders. As Katerina Zacharia (2021), its writer, director, and producer puts it, the film is part of a broader project which sets out to raise “awareness about the state of the church building,” and consequently promote fundraising for its restoration. A parallel aspiration is to produce an ethnographic documentary—significantly via an artistic angle—which represents the “place [of Hagioi Theodoroi] in the memory and identity of the village.” This dual orientation makes this fifteen-minute documentary a fascinating project which faces an immense challenge: how to balance strategies for moving audiences to support the preservation initiative, and at the same time to envision narrative techniques for adhering to the ethnographic ethics and politics of inclusive documentation. My analysis zooms on this predicament. It makes its task to identify the documentary’s strategies of representing this heritage site and reflect on the ideological implications of its narrative choices.

To piece together its story, Blessings and Vows relies on ethnographic documentation via interviewing. It privileges, that is, the authority of voice, featuring the perspectives of local villagers, a Greek American who lives between the village and Haverford, Connecticut, and two archaeologists. These micronarratives take central stage in the telling. The documentary has no external narrator; the interviewer is off camera, and we do not hear her probing, so these narratives, given by a small sampling of subjects, come to exclusively define the story. The interviewees assign value to the historical church by foregrounding its emotional, historical, ideological, and social significance, and, in turn, offer reasons for the necessary restoration of this building now in immediate danger of physical dissolution.

Without the filmmaker’s mediating presence, the narratives acquire the effect of direct immediacy, as the voices speak for themselves without contextualization, reflection, or resistance. We hear the voices of the interviewees, both literally and figuratively. By figuratively, I mean in the broad use of voice as a trope to convey a position, make a claim, or assert value, as well as the willingness to act upon a voiced value toward materializing a purpose. Blessings and Vows documents and circulates local, metropolitan, and diaspora voices that, taken together, uniformly call for the preservation of an ethnoreligious heritage site.

I discuss Blessings and Vows from the perspective of voicing, which, as Amanda Weidman notes, “emphasizes the strategic and politically charged nature of the way voices are constructed” (2014, 42). In other words, voicing directs attention to the social construction of a cultural text within a set of power relations. It asks a host of interrelated questions: how does a cultural text—like a documentary film—deliver its interests? Who is offered space to speak, and from which position does one speak? What is legitimized, what is contested, and what remains unsaid? What is the role of cultural producers in meaning making?

I examine this visual narrative therefore in relation not only to the interests of the interviewees it features, but also to the voicing shaped by the filmmaker through the documentary’s representational perspective. Given this centering on voicing, I would be remiss not to explicitly voice my own voicing too. As an immigrant-academic whose biography connects with an embodied knowledge of how small-town norms such as patriarchy, nationalism, and anti-intellectualism tend to inflict symbolic and often material violence against alternative subjectivities, I embrace scholarship which foregrounds the plurality of voices within a locality and pays attention to those mechanisms which seek to silence them. It is from this position that I read Blessings and Vows. While I support the restoration of Hagioi Theodoroi, my task lies elsewhere: to critically engage with the manner in which the documentary brings local memory and identity into representation and subsequently reflect on the implications of its representational practices.

My interest in Blessings and Vows springs partly from the challenges the film confronts to represent the village via the lens of its dual purpose, namely, as I have noted, support for heritage preservation and fundraising on the one hand, and the ethnographic documentation of local memory, identity, and heritage on the other hand. I ask how its filmmaker—who is also an academic with an expressed interest in cultural politics—works out to negotiate this predicament. What does the balancing act enable, what values are privileged, and what are the ideological implications of the chosen narrative solutions?

Evidently, Blessings and Vows delivers its voicing through selective inclusion. That is, those who unambiguously support the restoration of the monument are given a voice, and this voicing is delivered via narrative segments chosen by the filmmaker. As the interviewer has opted to place herself off-camera, we are left without a layer of reflective commentary from her part. In addition, the scope of the questions to the interviewees—or the filmic editing of their narratives—is attentively modulated. While the film expressly sets out to document local social memory, there is no probing into the crucial question regarding the various human, cultural, and political processes responsible for the church’s dilapidation (see Hart 2021). The voicing of the film shields the audience from the potentially controversial local politics and conflicts of interest associated with the history of heritage preservation in the locality.

There is of course a plurality of perspectives within the film, each asserting a different value for the church. In fact, as anthropologist Laurie Hart (2021) observes, the various stories are “somewhat at odds” with each other, even contradictory in the ways they mark the significance of the site. Within this internal plurality, however, the unity of purpose is undeniable. The interviewees cite multiple motivations—religious identification, historical importance, aesthetics, affect, and identity—to collectively claim value for the restoration project.

Take for instance the voice of Metaxia Anaplioti, an elderly villager who had assumed the responsibility of caring for the church until her recent death shortly after the filming. Her daily devotion to one of the patrons of the church—embedded in the practice of her vow—animates the crumbling monument, it literally and metaphorically gives life to a church whose bell is now silent, as a local put it (“η καμπάνα έχει σιγήσει”).

The voices of other locals express religious sentiment and affect too, but they also reference economic and social value, as for instance the importance of the place as a tourist destination; or, for this depopulated place, as a restorative act for the village’s social life. Other voices, such as those of the archaeologists assigned to the study of the monument, underline its historical and artistic significance as well its centrality for village social life—a statement palpably mistaken, as Hart notes (2021). What is more, the Greek American perspective emphasizes both aesthetics—the physical site as beautiful—and identity—tangible heritage as a source for national identification across diaspora generations.

The language of folk religious devotion, the language of affect, the language of beauty, the language of identity, the language of historical knowledge, the language of economy, the language of village revitalization—all these represent the language of the faithful, the locals, the diaspora, and professionals assigned with the stewardship of the past. They coexist, sometimes overlap with one another, and advocate from different positions. But although several different voices are presented in the film, each with their own personal and social interests, the film itself establishes one singular voice, a collective consensus about the value of restoration around normative values.

Blessings and Vows operates within a web of political and cultural power relations that implicates local, regional, religious, national, and diaspora interests—the Greek Orthodox public, for instance; the Greek state; agents of regional tourism and economic growth; scholars; and philanthropists everywhere who advocate for this heritage. Significantly, it was upon the request of the “local office of the Ministry of Culture” that the film’s Executive Producer, Sharon Gerstel, got involved “to help raise funds to restore the building” (2020a, 34). In this respect, the interest of Blessings and Vows in featuring a variety of motivations for preservation enhances its potential to resonate with multiple publics for the purpose of fundraising.

The inclusion of a Greek American voice is indicative of the film’s interest to recognize—and speak to—a public vested in a Greek Orthodox identity, the diaspora. It is the voice of Demetris Panteleakis, whose family’s transnational life involves regular returns to the village to which he affiliates through ancestral ties. Panteleakis’s voice and voicing represent more than affective ties with the church; it connects with his transnational preservation engagement. He directs The Byzantine Church Preservation Foundation, Inc., a Massachusetts nonprofit organization started in 2019, whose aim is fundraising for this restoration project (Gerstel 2020a, 39fn.28).

The inclusion of his voice in the film acknowledges a larger cultural phenomenon, the enduring attachment and investment of the diaspora to places of family origins, tapping into a long history of diaspora’s “communal investments in restoring old churches” (Kourelis 2020, 88). By incorporating the Greek American endorsement, spoken in English, whose ethnoreligious valuation is positioned to resonate with this diaspora’s sizable Greek Orthodox population as a cause worthy of support, the film recognizes this ethnohistoric reality.

Although Panteleakis’s micronarrative is somewhat elliptical, its basic position and assumptions are readily recognizable. Panteleakis’s story is one of roots and the valuing of tangible heritage, such as the church, as a means for making identity. What matters in his perspective is diaspora’s encounter with the material remains of the historical past. For diaspora generations, the encounter with ancestral local heritage invites historical inquiry, produces knowledge, and functions as a resource for identification. Hagioi Theodoroi, a Byzantine place of religious worship, stands today as material evidence of ethnoreligious endurance and survival in connection to grave historical threats. The narrative of heroic struggle for survival represents of course a technique for making or reinforcing identity. Indeed, “the church is viewed by the community as a part of an unbroken link to the past, a past that is seen as continuous” (Gerstel 2020a, 34).

In addition, the Greek American voice adds a patriarchal inflection to this narrative. Panteleakis speaks of a boy’s baptism, which takes place in front of the church, and is particularly celebrated for being the first in approximately one hundred years. We watch the ritual and hear the gunshots fired in celebration of the boy’s rite passage. “We are anarchists, and we are true Greeks … and our youngest males are called ‘guns’ when they are born,” he explains, linking the strong regional gun culture of the Mani with both traditional notions of “maleness” and the reproduction of what it codes as authentic Greekness. The narrative creates a center for identity by connecting an ethnoreligious monument with local self-perceptions of national identity and gendered performances of masculinity. The film documents the link between a patriarchal version of Greek identity and heritage restoration, though it does not comment on it; to do so, to probe the ideological implications of this linkage, would be beyond the promotional aspect of its voicing.

Heritage discourse expresses contemporary interest about the past, with a future inflection. Hagioi Theodoroi is seen as a material site attaching temporality to identity. The monument nurtures an individual’s and a community’s connection with the historical past, which in turn anchors diaspora identity in the present. The advocacy to restore and preserve to ultimately pass the past on to the next generation speaks about the future orientation of heritage. This affective and ideological claim centers the interest in the restoration.

Let us further reflect on the diaspora voice: preserving heritage, Panteleakis states, is a “a gift we need to give to every child we have” (emphasis mine). The framing of preservation as a gift is a particularly Greek American construct. That is, the notion of passing on heritage as a gift appears often in the Greek American conversation about preservation. In the diaspora, where the question of cultural reproduction is an ever-present problem, preservation requires continuous material and symbolic investment. The value attached to preservation and the material investment it generates is offered as a gift to the next generation, often connected with the purpose of reproducing family memory. It is not rare for that gift to bring about the moral obligation for further gifts across generations. A chain of generational gifts. A story of the diaspora could be told as a story of gifts and countergifts in connection to the ideologies informing the giving.

It might be said that Blessings and Vows becomes part of this story from a Greek Orthodox point of view. Because it assembles a range of selected voices toward a deliberate purpose—to raise funds for the deserved preservation of an ethnoreligious monument—it serves as a contemporary countergift to those who have worked in the past to preserve Greek Orthodox and Byzantine heritage. Its voicing seeks, of course, an audience. The film amplifies its public resonance when it features a variety of motivations for preservation around a dominant narrative of ethnoreligious endurance and the obligation to ensure its continuity.

Unlike classical heritage, which has no community of users to contest its monuments, Byzantine heritage belongs to a living faith tradition that is deeply interwoven with power, ideology, and politics. Occasionally, the voice of the church may intersect with the voice of the Enlightenment (through the science of art history and archaeology) or the voice of diasporic modernity (through a permanent nostalgia for, or attachment to rural origins). Through its uncontroversial telling, the film positions itself to tap into this power of various institutions—the church, the state—and the communities and subjectivities they inspire. It enhances its value by empowering normative and officially sanctioned heritage advocacy.

Although the film gives value to various voices, the presence of a singular dominant voice, that of Metaxia’s, is unmistakable. For her, folk culture—as indicated in her performance of the folktale opening the film—and devotional practices—as embodied in her personal relation with “her Theodore” (Hart 2021) in her practice of vow—commands a central place in her life. She represents a “folk subject” for whom the abandoned church served in fact as a sanctuary outside dominant practices (social relations in the village), institutions (family), and narratives (patriarchal associations with guns and male national identity). For this woman whose dire poverty is intertwined with a life of suffering, Hagioi Theodoroi offers a place attached with a different mode of existence: a “certain kind of spatial, moral, and imaginative freedom outside of village territory (literal or metaphoric) and family” (Hart 2021). But also, her immersion in a folk devotional commitment comes about as the result of her consent—some might say “subjection”—to a powerful religious narrative in Greece with a particular appeal to the poor, to women, and to the marginalized (Dubisch 1995). The image of Metaxia’s slim figure animating the church’s interior dramatically contrasts with images of the near-abandoned monument, attaching an affective narrative component to the film’s voicing. Her performative expression of suffering deeply moves the filmmaker, generating empathy across socioeconomic difference. The figure of Metaxia serves a redemptive function in Blessings and Vows, offering a morality lesson: the enduring commitment of her religious devotion provides an antidote to modernity “when all relationships seem so trivial and fleeting” (Zacharia 2021).

In the semiruined church of Hagioi Theodoroi, Metaxia finds a home among the ruins of her life, inserting and asserting herself within a place now extolled as heritage monument. Can the tensions between the folk and the official that surround this intersection help us expand our reading of Blessings and Vows, or even move beyond its voicing? For, the interest in producing heritage around normative values for the purpose of fundraising outweighs the ethnographic aim of understanding the local politics of heritage as well as anthropology’s commitment to critical reflection (see Marcus and Fischer 1986).

To unravel this line of inquiry, let us not forget that the voices and voicing of scholars participate in shaping the meaning of a cultural text. The critical reception of Blessings and Vows is not an exception. In her analysis of the film, Hart (2021) offers incisive insights about the place of Metaxia’s folk practices in a heritage site that is now officially sanctioned as worth restoring. Metaxia’s possession of the church via vernacular practices will no longer be possible to sustain in the planning of turning the church into monumental heritage. In her departing words—both in the context of the film and, as it turned out, her ultimate farewell, given her death a short while after—she is conscious of the turning point to come. Hart notes:

But her Theodore is not embodied in these things [liturgical objects that the church, as she emphasizes, needs], and as she says at the end of the film, what you—who are adopting it for some reason now and who will put back the columns and books or some version of them—what you do with this church is “your decision,” and not really her business.

The hypervisibility of the desired monument is bound to eclipse some or radically alter other personalized possessions of the place via vernacular practices. The poignant question that Metaxia poses is about the responsibilities of those who designate themselves as future stewards of this heritage site. But her statement also raises the question about her life’s connection—her life’s story—with it, aspects of which Blessings and Vows documents. Those involved in the voicing of heritage preservation—scholars, cultural producers, the public, locals—may wish to ask, along this line of thinking, what to do with the host of unofficial practices that monumentalization disrupts, even relegates to the margins or oblivion.

With Metaxia’s death “she closed one door, and another opens,” Hart writes. Here I wish to direct attention to available openings carved by scholars and nonacademics in the interest of empowering a broader project of reclaiming those voices which are involved in creating heritage against normative narratives. For my purposes I will outline a particular transnational facet, albeit briefly and partially, of locating and excavating heritage, which focuses attention to the personal and familial—embodied as memory—and private or barely traceable—expressed as material culture.

This opening is taking place within the renewed academic interest in the Greek village,2 which builds on seminal ethnographic and archaeological scholarship in the 1960s, 1970s and beyond (see Sutton 2000; Forbes 2007) to reinforce the idea that the various heritages intermeshing with social life of a village cannot possibly be narrated outside human mobilities, cultural change, exchanges, and geographically far-reaching networks of connections across economic systems. It is impossible to narrate the Greek village outside the constitutive effect of transnational relations (Tourgeli 2020).

Significantly, Blessings and Vows is also located within this

terrain. Its making takes place within a web of transnational relations

involving U.S. academic institutions, cultural producers, and diaspora

networks, as well as the Greek government, regional interests in Mani, and

the locals of Vamvaka. A product of Los Angeles–based scholars with

professional ties to Greece, the documentary strengthens connections and

affiliations already in operation between U.S. West Coast institutions and

southern Greece. The Mani peninsula is an object of academic interest for

the film’s Executive Producer, Sharon Gerstel, a distinguished scholar who

works “on the intersection of ritual and art in Byzantium and the Latin

East.” Transnational

linkages are also at work at the level of institutional heritage activism.

Demetris Panteleakis, as I mentioned, directs the nonprofit organization

established in the United States for the restoration of the church. In

addition, the availability of the bilingual film in the internet adds yet

another facet in its operation across Greek and Greek/American worlds.

The Greek village represents a par excellence transnational topos when it comes to the question of heritage. Vernacular architecture, traditional occupations, and crafts (such as stonemasonry), the material folk culture of houses (decorations, trousseaus, signs of identity), and the experiences and memories of its inhabitants are intimately—often physically—intertwined with migrant remittances as well as values, ideas, and material transported across continents and regions. It is a habitat produced at the intersection of the local, the national, and foreign modernities, an environment whose immense complexity includes both tangible material objects—often in ruins or with the faintest of material traces—and intangible stories—often forgotten, suppressed, or not even told. In this network, another affective dimension is at work: the ancestral home in the village as a past that possesses value for individuals in the diaspora who are moved to recover, reclaim, and preserve family heritage.

Of course, attention to transnational processes is not in itself a panacea for locating nonhegemonic vernacular heritages. In fact, Blessings and Vows as well as other filmic examples demonstrate that transnational transactions increasingly incorporate—even propose, as in the case of the film My Life in Ruins—banal nationalism as a mode of Greek belonging and diaspora identity via heritage (see Anagnostou 2015). But because transnational mobilities often take place in the context of symbolic and material violence inflicted by institutions—poverty, loss of property, ideological persecution, and the much-discussed recently networks of illegal adoptions (Van Steen 2021)—as well as cultural normativity—intolerance to difference and alternative subjectivities—they shape an ethnohistorical terrain dotted with dislocations, silences, ambivalences, tenuous connections, and partial identifications with heritage. Contemporary voices and voicing seeking to connect with that past are confronted by voicelessness in the material and discursive archive. The doors that Metaxia’s death open have often been shut close by the iron gates and the gatekeeping of nationalist and ethnoreligious appropriations of the folk.

The construction of the village as the repository of national identity provides a historical framework to explain this marginalization. It is well established that with the foundation of the discipline of Greek folklore in the 1870s, the Greek village and rural life served the necessary link for a modern Greek identity built on the triumvirate of classical antiquity, Christian Byzantium, and rural folklore. The field of folklore, or laografia, gave the scientific underpinning for the ideology of three great ages canonized in Constantine Paparrigopoulos’s history. This discourse disciplined the complex social and cultural realities of village culture, its official renderings reducing the folk into the embodiment of a single national voicing. The ideology of the village has armed Greek patriarchal nationalism in various projects of violence: racial and sexual intolerance, the persecution of alternative political and cultural voices, the oppression of women, and the exclusion of marginal communities. Because of the harm it has inflicted—and to some extent continues to exact today—on a wide range of nonnormative subjects, it confronts scholars with an ethical and political imperative to keep disrupting its power.

How to reclaim multivocality in the making of vernacular heritage? How to locate voicing that disrupts official ideologies of national and cultural normativity? Turning to an ethnohistoric exploration of transnational mobilities, for the reasons I have explained, presents a potential site for expanding the ideological scope of “finding” and preserving vernacular heritage. Several practitioners in the proliferating academic interest in the Greek village recognize the importance of excavating overlooked transnational networks that have contributed to its making throughout history. The excavations, both literal—archaeological digging—and discursive—recollection of the past—value the forgotten and silenced family story as well as the documentation of abandoned, decaying, destroyed, and lost homes. This voicing privileges the personal, the discontinuous, the fragmented, and the unofficial; the nonmonumental. In this interest, the involved scholars take cues of diaspora voices and voicing that produces poetry, memoir, and oral history to excavate frail “threads of meaning” about family journeys across borders, traumas, dislocations, cultural mixing, and loss (Kourelis 2020, 99). Those who research the transnational village from this lens derive inspiration and find valuable building blocks of knowledge in these diaspora voices and voicing that for the most part are deprived broad public visibility. In this interfacing between diaspora interests in family heritage and academic voicing of alternative heritages the space opens for public scholarship that could direct its funding efforts to institutions such as universities, heritage societies, foundations, research centers and those individual donors who are open to polyvocality in heritage.

Blessings and Vows reminds us—if we needed a reminder—of the power of visual narration as a tool for public humanities. Two questions present themselves as a frontier in the domain of academic preservation activism and its popular narration: the question of giving voice to the unofficial archive in popular narratives, and the question of voicing values that might go against the grain of prevailing ideologies. Related, of course, is the question of securing funding, which inevitably follows us as a steady companion. Our commitment to bring to the public the voice of the nonmonumental and nonnormative should be matched, it seems, with the resolve and ingenuity to keep generating resources for this all-important voicing.

Yiorgos Anagnostou

The Ohio State University

Yiorgos Anagnostou

teaches Modern Greek diaspora and transnational studies at The Ohio State

University. He writes about Greek America in academic journals, community

publications, and the media in Greece and Greek America.

Editor’s note:

This essay is part of a triptych of writings about Blessing and Vows. For Katerina Zacharia’s “Into

the Light: Making Blessings and Vows” see here. For Laurie Kain Hart’s “The Uses of

Abandonment: Reflections on the Film Blessings and Vows” see here.

Notes

1. A version of this work was presented in the panel “Cultural Heritage Discourses in a Greek Rural Village”—organized by the filmmaker, Katerina Zacharia—at the 26th Modern Greek Studies Symposium, November 7-10, 2019, in Sacramento. I found much inspiration in the presentation of my copanelist Laurie Hart. The insightful reading of early versions of this work by Kostis Kourelis and Artemis Leontis opened paths of inquiry.

2. See for example “The Greek Village,” a Symposium at the UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, February 22-23, 2019. The symposium papers were published in a special section in the Journal of Modern Greek Studies, with Sharon E. J. Gerstel (2020b) as Guest Editor.

Works Cited

Anagnostou, Yiorgos. 2015. “Within the Nation and Beyond: Mediating Diaspora Belonging in My Life in Ruins.” FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies 3 (October). https://filmiconjournal.com/journal/article/pdf/2015/3/1

Blessings and Vows. (2018). Written, directed, and produced by Katerina Zacharia. Athenoe Productions.

Dubisch, Jill. 1995. In a Different Place: Pilgrimage, Gender, and Politics at a Greek Island Shrine. Princeton University Press.

Forbes, Hamish. 2007. Meaning and Identity in a Greek Landscape: An Archaeological Ethnography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gerstel, Sharon E. J. 2020a. “Recording Village History: The Church of Hagioi Theodoroi, Vamvaka, Mani.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 38 (1): 21–41.

———. 2020b. “Introduction.” Special Section: Perspectives on the Greek Village. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 38 (1): vii–x.

Hart, Laurie Kain. 2021. “The Uses of Abandonment: Reflections on the Film Blessings and Vows.” Erγon: Greek/American Arts and Letters, December 31.

Kourelis, Kostis. 2020. “Three Elenis: Archaeologies of the Greek American Village Home.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 38 (1): 85–108.

Marcus, George E., and Michael M. J. Fischer. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sutton, Susan B., Ed. 2000. “Introduction: Past and Present in Rural Greece.” In Contingent Countryside: Settlement, Economy, and Land Use in the Southern Argolid Since 1700, 1–24. Stanford University Press.

Tourgeli, Giota (Τουργέλη, Γιώτα). 2020. Οι Μπρούκληδες: Έλληνες μετανάστες στην Αμερική και μετασχηματισμοί στις κοινότητες καταγωγής, 1890–1940 [The returnees: Greek immigrants in the United States and the transformation of origin communities, 1890-1940]. Athens: National Centre for Social Research.

Van Steen, Gonda. 2019. Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece. Kid pro quo? University of Michigan Press.

Weidman, Amanda. 2014. “Anthropology and Voice.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43: 37–51.

Zacharia, Katerina. 2021. “Into the Light: Making Blessings and Vows.” Erγon: Greek/American Arts and Letters, December 31.