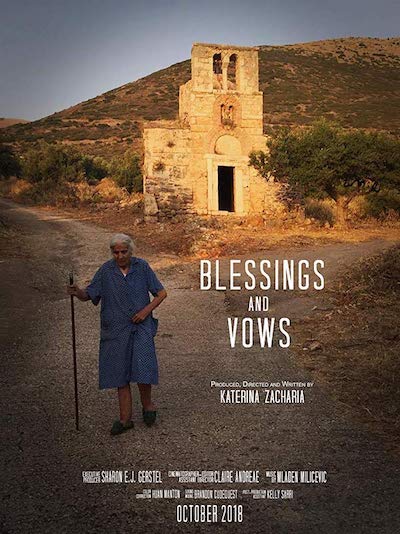

The Uses of Abandonment: Reflections on the Film Blessings and Vows1

by Laurie Kain Hart

This lyrical fifteen-minute film explores the potential reconstruction of an eleventh-century Byzantine church in a depopulated village in the Mani peninsula, in southern Greece.2 It raises a host of questions concerning the relations with history and built form that are sustained by local villagers and their diasporic kin, as well as by metropolitan archaeologists and filmmakers.

The possibility of the church reconstruction project, which requires a very large financial investment in the terms of national archaeological economies, and certainly all the more so relative to the state of local rural economies, raises the problem of identifying what value the building, and its resurrection from ruin, has, and to whom.

In what follows, I want to focus on some of the embedded structural relations—specifically of gender, nationality, and class—that undergird the ethical and aesthetic assumptions about reconstruction that are on view in the film, some of which we ourselves might reflexively hold. I should probably say at the outset that I am all for the repair and maintenance of this beautiful church. But I am also interested in understanding what the church as it is now does, and in exploring the inevitably perverse effects of interventions (knowing that, of course, any move that we make, as historical actors, has these kinds of effects.) For this, I explore the hopes for reconstruction and the values attached to it by the people we see in the film—including, of course, Metaxia herself.

Projects of reconstruction are complex interventions into processes of destruction. Whether we perceive the human agent or not—clearly recognizable in the case of war (think Dresden, Bosnia, Iraq, Yemen), less visible when we talk of abandonment or the “entropy” attributed to time—the decline of infrastructure is always a case to be investigated. Decline and decomposition are not the product of an agentless force, but, like death in a folktale, always the result of the actions of a culpable agent. The first question to be asked, then, is why this church is in such a state of dissolution that it should require radical reconstruction.

Beyond what I have seen in the film or learned incidentally from ethnographic monographs, I know very little about the village pictured here, or about any of the people in the film, or about eleventh-century Byzantine churches in Mani. I do draw on two specific comparative terrains in thinking about this question. The first is my 1980s field research on rural religious practice in the eastern Parnon peninsula of Laconia. (I am obliged to note that people in the Parnon tend to have a kind of insubordinate, deflationary view of Maniot self-identifications, but they also share a number of exceptional cultural and social features with these fellow Laconians.) The other domain I draw on in thinking about this ruined church is my research on buildings and ruins, both in urban Philadelphia (of all places) and in Greece, both in western Macedonia, and in Leros, in the eastern Aegean. These examples lead me to pose certain questions about material degeneration and the uses of infrastructure from the past. They have taught me that there is always an interesting reason buildings are left to “fall apart” and that a blighted or half-dead building tells a story of much more than simple neglect. In Philadelphia, for example, the active flight of population from the old factory neighborhoods and the—again agentively—concerted lack of public and private investment over the last forty to fifty years has left entire blocks or rowhomes crumbling. However, as Robert Fairbanks demonstrated in his brilliant neighborhood study How it Works (2009), it is precisely because they were physically degraded and reputationally stained that the houses came to occupy a central, productive place in making viable the lives of the poorest of the poor, the ex-incarcerated, the addicted, that is, in providing housing to the indigent. From Macedonia and Leros, I learned that abandoned or disused infrastructure also presents a national question, and that the exploitation of architecture or the persistence of disuse does not necessarily signify indifference or incapacity but rather constitutes a politically powerful act of communication and, often, policing.

Let me return to Vamvaka:

In the film, villagers in Vamvaka express their relationship to this semiruined building in terms of ideas commonly received in Greece about family, identity, time, and history as key sources of social and personal value in the twenty-first century. Perfectly articulated in Margaret Kenna’s work in the 1970s, it is an axiom of our ethnographic understanding of rural Greece that church buildings and graveyards, and the substances and property exchanged between houses, churches, fields, and graves are, as Kenna wrote, “the physical expression of rights and obligations [that villagers] consider to be the most important and profound aspect of the relationship between the generations”—and therefore constitutive of the self as the critical resources of social and spiritual identification (1976, 21).

As a liturgical building, the church of Hagioi Theodoroi (the Saint Theodores) is not strictly necessary to everyday village life in the present. The inhabitants of Vamvaka have a “modern” village church in which the requisite regular liturgies are celebrated. Indeed, Sharon Gerstel points out that a priest’s preference for this new church may have been a significant cause in the abandonment and degradation of Hagioi Theodoroi (2020, 24).3 Hagioi Theodoroi is remembered principally as a funeral church: it lies on the road to the cemetery, but not within it. Neither outside nor inside, not quite an exokklisia (a church beyond the village limits, visited occasionally) but no longer at the core, it stands above the village, at a breathable distance, surrounded by threshing floors and on the path to the winter pastures.4 In this sense, for the villagers its liturgical assignments and the special ecclesiastical significance of the Theodores for whom the church is named are no longer marked, and the church is freed up to adopt new significations. If at one time, the priest and his family might have had interests in and responsibilities for the material property itself—the structures, the grazing land, the cisterns—it seems now to be everyone’s—and no one’s—object, communally bequeathed and vaguely left to ruin, apart of course from the special claims of Metaxia Anaplioti, the elderly woman who lights a candle every afternoon at four or five o’clock to ensure that the saints have not been abandoned in the dark.

The value residents assign to the church is expressed as an “emotional”—synaesthematiki—value, and not only for Metaxia, but also for the others, the middle aged and aging who are left behind in the village by the great migrations to the cities and abroad. And, equally important, the church takes on a special emotional value for those kin who have moved on but throw an anchor back to the village to ensure that they too do not get entirely lost, out there in the world.

A few dates may help us also situate ourselves as viewers: according to the villagers, who, like the archaeologists, recognize and feel the folkoric and cosmopolitan force of the “early” date of a monument, the church was built sometime in the eleventh century (specifically, in 1075). Metaxia was born in 1938 or 1939, at the beginning of World War II. Her mother died when she was five, in 1944, at the beginning of the Civil War. We are told that the last epitaphios (funeral liturgy) was celebrated at Hagioi Theodoroi during this time, in the late 1940s. The last baptism was celebrated long before that, around the time of World War I. The dates remind us that the century and Metaxia’s life were saturated in war.

In fact, these poor Theodores, after whom the church is named, appear to be soldier-martyrs themselves, albeit with a world-renouncing mission. One, the Anatolian Theodore called “Stratelates,” the Commander, was cruelly tortured and killed by the awful fourth-century Emperor Licinius and then subsequently miraculously resurrected, only to insist on surrendering himself a second time to be definitively beheaded and martyred. His signature gesture was to smash the gold and silver idols given to him by the emperor and donate the fragments to the poor, thereby illustrating the soullessness—if also paradoxically the usefulness—of material things. The other, St. Theodore Tyron, the “Recruit” (a junior avatar of the Commander Stratelates although he appears to have predated the Commander), is also is a patron saint of soldiers. He slew a dragon, saved a princess, and then he too smashed a host of pagan objects to demonstrate, in the words of the traditional hagiography, “the absurdity of regarding as a deity a lifeless piece of wood that is reduced to ashes in a few moments.” When the Emperor Julian the Apostate threatened to pollute all the markets in Constantinople with the blood of sacrificial animals, this Theodore also invented kollyva (the mixture of grains that is conventionally distributed to mourners at Orthodox funerals) to keep Christians cleanly fed; he was certainly destined to head up a funeral church. The Saints Theodore remind us, in case we have forgotten the lessons of iconoclasm, that the artifacts of the church—and the church itself—maintain a precarious theological position vis à vis the distinction between veneration and worship, icon and idol, the double nature of Christ as man and god, and the symbolic and the real. The Theodores might be said to occupy a prelapsarian moment in Christianity when its history was thin, its representations few, and the paradoxes of holy images and objects signaling both too much attachment to the world and the immanence and beneficence of God were yet to come.

But the bellicose associations are resurrected in the film by the expatriate from Hartford, who so proudly embodies a specific, familiar ancestral male villager: the legendary patriarchal, gun-toting, baby-boy-celebrating Maniot rebel. “We are anarchists, and true Greeks . . . At the birth of a child, at a wedding, at a baptism, the guns come out, because our youngest males are called guns when they're born.” For this U.S.-born son of Vamvaka, the project of reconstruction bolsters the patriotic, national, and genealogical Greekness with which he is deeply identified. His support and affection for the church concerns “knowing who you are and where you come from,” that is, knowing yourself as a “true Greek,” and always, abroad or at home, a native with native claims. A certain distance, he reflects, allows an outsider to see and resurrect the beauty and significance of the church for those villagers who have grown blind to it as a familiar feature of their landscape. This tangible and intangible heritage—paternal house, church, village, myth—is his bequest to his children.

For their part, the monimoi, the full-time residents of Vamvaka, recognize diverse values connected to the church. They recognize that value is conferred by the church’s antiquity and craftsmanship, as well as by its so-called authenticity, its localism or terroir (to borrow a gastronomic term), and that they have an agentive part to play in this creation of authenticity. Perhaps a little guiltily, they acknowledge Metaxia’s special “emotional” relationship to the church; they seem to edge closer to her as they embrace her as their representative whose ritual labor proves the church's authentic significance to the village. Yet they seem pressed to find other proofs of a special intimacy: one man remembers that as a boy he used to scramble up the belfry and ring the bell to annoy his elders. Otherwise, villagers have mostly their worry to offer. They have been watching with concern as tree branches invade the walls and earthquakes break the stones.

But they are exhausted. The church defeats them. Apologetically, they say they take care of the church oso mporei (to the extent that we can). The church at this juncture becomes a metonym for the village. To revive the church is to revive the life of the village. The reconstruction would be an “investment in the soul” and a pragmatic investment—for “touristic reasons.” It is also beyond their powers. The archaeologists, for their part, recite a somewhat anachronistic and contrary-to-fact mantra about how the church—and here they invoke the ethnographic present, which freezes time in a generic, ideal-typical, descriptive frame—is the center of village life, which palpably this one is not. And yet, powerfully, one woman reflects, wringing her hands, that the potential reconstruction of the church will show that “something can still happen.” She expresses not only the beleaguered hopes left by the recent and enduring economic “crisis” but of a lifetime of waiting. If “the experience of submission to domination is one of endless waiting” (Auyero and Swistun 2009; Bourdieu 2000), we have a hint, in this posture of tired anticipation, of marginalization by and subordination to “global hierarchies of power” (Herzfeld 2004) that lies beneath this collective pride and bravado.

We could borrow the anthropologist Fred Myer’s observations on contemporary Australian aboriginal acrylic painting to summarize the layered emotional and pragmatic dimensions of what the villagers tell us in the film about the church. There too, the significance of valued artifacts is found in a relationship to a territory, and the presence of the past, and much more. Myers writes:

[Aboriginal painters] include [as reasons for painting]: painting as a source of income, painting as a source of cultural respect, painting as a meaningful activity, defined by its relationship to indigenous values (in the context of “self-determination”), and also painting as an assertion of personal and sociopolitical identity expressed in rights to place (1991, 66).

Like Aboriginal acrylic painting on the global market described by Myers, the architectural reconstruction of Hagioi Theodoroi is a globally synthetic act that reveals the conflicted, persistent, and vulnerable nature of forms of local/transnational value among the array of rights, profits, and futures afforded by the idea of reconstruction. In his richly comparative approach to art as a “technology of enchantment,” anthropologist Alfred Gell (1998) argues that every human-made artifact—from a net to a painting to a building model made of matchsticks—is buzzing with a complex network of what he calls “agents” and “patients,” patrons and subjects, makers and viewers. Objects of “art” hum with action. The church “resists,” in Gell’s terms, our capacity to fully grasp the weight of its stones, its symbolic complexity, the mystery of its composition, and its life-chances, and turns into a “sticky” thing that is a magnet for the drama of social relations.

There is, of course, another story in this film, the story of Metaxia, around whom the narrative revolves. What does she tell us about this church and its reconstruction, and why? Metaxia’s telling of the legend of Areti, her own autobiography, and her commentary on her ritual actions give us a different, and personal, story of this church, idiosyncratic but bound within a frame of gender-scripted possibilities.

Applying a probably too-weighty triple lens from feminist theory, psychoanalysis, and existentialism, I argue that although her fellow villagers attach to the church and to Metaxia’s devotion a narrative of communal identity and convention, her commentary is somewhat at odds with theirs. Not only this, but it would have been impossible for Metaxia’s own nearly fifty year project to survive the planned reconstruction. As it happens, Metaxia died shortly after the film was shot. With her death she closed one door, and another opens.

First, Metaxia tells us that she lights the candle in fulfillment of a vow she made when she was forty, after being hit by a car in Athens. Although the church is dedicated to and called after the plural Saints Theodore, Metaxia’s promise is to one singular Theodore, whose icon we glimpse when she kisses him in the church. She is the only one to speak about the singular Theodore. This is her Theodore, and it is not identical to the Theodores who belong to the others. The church, as I wrote above, is not an everyday church. It is a church for the celebration of funeral liturgies and the epitaphios. It is where people were mourned before burial. The walk to the church with her walking stick was clearly arduous during Metaxia’s recovery and remains so in the time of the film. Her vow is a classic religious sacrifice, a deal for the deferment of death, an intimate exchange of pain and nourishment between a human being and her personal, sacred ally. Hades is the main subject all through her story. Her small walk is reminiscent of longer, more spectacular pilgrimages devoted to this complex, mediated, reciprocity with death (cf. Kristensen 2011).

Metaxia selected this particular church for her purpose precisely because it had come to be marginal and she could take possession of it. She takes intimate pride in its power to work miracles and in the mystery of its construction: she tells us that it was built (like the giant bridges attributed to Herculean ancestors in Greek fables) by oi palaioi, the “ancient ones,” creatures of superhuman strength who carried the river rocks uphill on their backs. It is not too much of a stretch to hear, in this description of their laboring bodies, echoes or projections of her own arduous struggle: a five-year-old girl orphaned by her mother in times of war and civil war and extreme poverty, hauling water and lighting fires, building a household out of nothing, tethered by a father and a sick sibling. When, in 1978, after her father died, she went to Athens to live with her sister, did she imagine, before she was hit by a car and seriously injured, that she might leave Vamvaka? If so the accident would have rendered wage-labor or domestic service impossible, and her consecration to St. Theodore was a decision that, as Sartre might say, gave her fate, her moira, in the absence of the intervention of tyche (chance), and in the now stark presence of mis-fortune, the character of an act of will. This existentialist reading makes sense to me as the only possible act of recuperation open to her, a poor rural unmarried woman in her time and place. Let me clarify what I mean via a short passage from Laing and Cooper’s Reason and Violence, concerning the writer and thief Jean Genet who so fascinated Jean-Paul Sartre. In his account of his own life Genet wrote, “I have decided to be that which crime has made of me” [my italics]:

Laing and Cooper (1999) write:

Since he could not escape fatality he became his own fatality. Since his life was rendered unlivable by the others, he would live this impossibility of living as if he had created this destiny exclusively for himself. This is the destiny he willed–he would even try to love this destiny… Sartre is at pains to stress that Genet’s “original crisis” can be understood only when seen against the setting of the French village community, with its narrow and rigid system of prohibitions, its high degree of cohesiveness, and the absolute value given to private property. . . (75)

Churches such as this one—by-passed, or neglected, or remote—are in Greece often staked out as sites of personal recuperation for women. I have argued before that they are sites of a certain kind of spatial, moral, and imaginative freedom outside of village territory (literal or metaphoric) and family (Hart 1992). Despite the dominant patriarchal narrative of the guns and familial identity, the church had this function for Metaxia.

This was not all. She tells us a story: a widow has nine sons, and one daughter named Areti. One of the sons wants to marry Areti to “a foreigner.” Areti’s mother demands that he promise to bring Areti back to her “in case of joy or sorrow.” The sons vanish. She is left all alone “like a solitary tree.” Presumably asked at some point to fetch Areti, the culpable son asks Hades for permission to bring her back—it seems the son himself is dead—and he does so. Areti arrives at her mother’s door and embraces her mother; her mother drops dead, as though her brother’s deadness (or her own) were contagious. Left all alone, Areti begs God to transform her into a bird.

This slightly modified version of the well-known folktale is an inversion of Metaxia’s own life. Let’s say that Metaxia’s mother is the one “married off to a foreigner,” Hades himself (marriage is a common paradigm, after all, for the estrangement of death, in a patriarchal society), and Metaxia the child is left at home all alone. She asks for her mother back, but her demand is unrequited. Later, leaving the village herself, Metaxia meets death in the form of the car accident. She makes a vow to Saint Theodore, survives, and the saint returns her to the village, transformed by the mandate, as Metaxia says of Areti, “to fly,” in perpetuity, “around the remote churches.”

The beauty, the aesthetic value of the church, is not irrelevant to Metaxia’s acts of devotion (Hart 1992, 155–56), but of greater relevance in her account of the church’s history is the labor entailed in hauling the large stones required to build it. Martyrdom is what Metaxia, and Metaxia’s Theodore, do well. Like her fellow villagers, Metaxia points out the insuperable problems with the physical infrastructure of the church. The columns and pavers have been stolen—presumably by people (villagers, foreigners?) who have taken them to make new dwellings or profit from them. She complains that the church needs repair and investment, that it wants its books and liturgical objects, and that this neglect is not “the way things are done” when they are done right. But her Theodore is not embodied in these things, and as she says at the end of the film, what you—who are adopting it for some reason now and who will put back the columns and books or some version of them—what you do with this church is “your decision,” and not really her business.

The archaeologist in the film tells us that we need to understand that “everything revolves around the church.” Metaxia tells us that this important place has, to the contrary, been plundered and ignored by everyone except a poor and suffering woman who has made it the core of her life, or rather remade it as the core of her life. As the church is reappropriated and restored in the hands of a national and communal project of development, for futurity and the paradoxical dreams of local prosperity and the reproduction of tradition, this feminine face, this territorial anarchism that is made possible by the ruinousness of ruins, is lost to the landscape.

Laurie Kain Hart

(M. Arch., University of California, Berkeley; Ph.D., Anthropology, Harvard

University) is Professor of Anthropology and Global Studies and Director of

the Center for European and Russian Studies at the University of California

at Los Angeles. Her research focuses on violence, civil war, ethnicity and

borders; space, architecture, art, material and visual culture; medical and

psychoanalytic anthropology and the public health risk environment; kinship

and gender. Her regional specializations include Greece, the broader

Mediterranean area, and the urban United States, about which she has

published widely.

She is currently working on a co-authored book, provisionally called

“Cornered,” analyzing the carceral and psychiatric mismanagement of U.S.

urban poverty and segregation in Philadelphia.

Editor’s note:

This essay is part of a triptych of essays about Blessings and Vows.

For Katerina Zacharia’s “Into the Light: Making Blessings and Vows” see here.

For Yiorgos Anagnostou’s “Voice and Voicing in Blessings and Vows: 'Finding' and Funding Heritage in the Greek

Transnational Village” see here.

Notes

1. Blessings and Vows (2018). 15 mins. Producer/Director/Writer Katerina Zacharia, Executive Producer Sharon Gerstel, Assistant Director/Cinematographer/Editor Claire M. Andreae, Music Composer Mladen Milicevic, Color Correction Editor Huan Manton, Sound-Mixing Brandon Cudequest, and Post-Production Assistant Kelly Sarri.

2. This paper was presented at the 26th Symposium of the Modern Greek Studies, November 7-10, 2019, in Sacramento. I would like to thank Katerina Zacharia for the invitation to comment on the film and for her edits on this article, my fellow panelist Yiorgos Anagnostou for his excellent presentation, and Sharon Gerstel and the MGSA audience for their questions and comments at the presentation.

3. Gerstel’s excellent 2020 article on the history and social significance of the church was published after the presentation and completion of this essay; I have added this helpful detail from her study.

4. Ibid.

Works Cited

Auyero, Javier, and Debra Swistun. 2009. Flammable: Environmental Suffering in an Argentine Shantytown. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2000. Pascalian Meditations. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fairbanks, Robert P. 2009. How It Works: Recovering Citizens in Post-Welfare Philadelphia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gerstel, Sharon E. J. 2020. “Recording Village History: The Church of Hagioi Theodoroi, Vamvaka, Mani.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 38 (1): 21–41.

Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Clarendon Press.

Hart, Laurie. 1992. Time, Religion, and Social Experience in Rural Greece. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Herzfeld, Michael. 2004. The Body Impolitic: Artisans and Artifice in the Global Hierarchy of Value . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kenna, Margaret E. 1976. Houses, Fields, and Graves: Property and Ritual Obligation on a Greek Island. Ethnology 15 (1): 21–34.

Kristensen, Regnar A. 2011. Postponing Death Saints and Security in Mexico City. Ph.D. diss. Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University.

Laing, R. D., and D. H. Cooper. 1999. Reason and Violence: A Decade of Sartre's Philosophy 1950–1960. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Myers, Fred. 1991. “Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings.” Cultural Anthropology 6 (1): 26–62