Into the Light: Making Blessings and Vows

by Katerina Zacharia

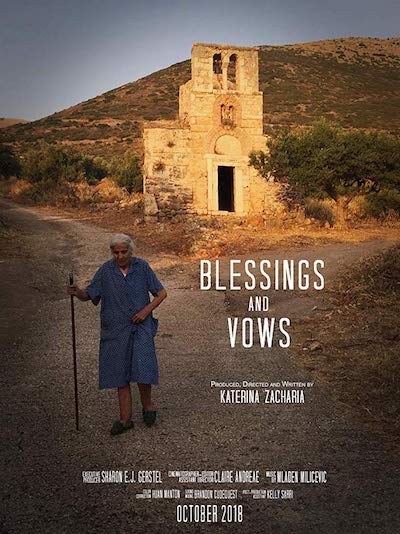

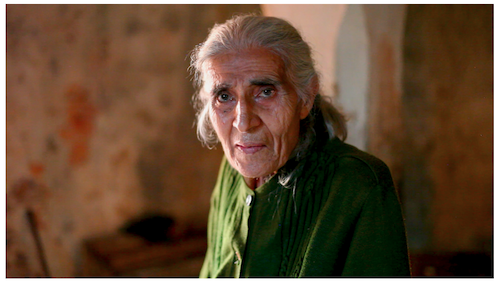

Metaxia Anaplioti is the luminous protagonist of the short documentary Blessings and Vows (2018), my first venturing into filmmaking.1 The octogenarian villager adhered to her vow, lighting a candle daily at the eleventh-century Byzantine church of Hagioi Theodoroi in Vamvaka, Mani in Southern Greece, for over 40 years.

I first encountered Metaxia, an elderly villager, leaning on her walking stick on a hot Saturday afternoon, on June 24th 2017, in Vamvaka, in the arid landscape of inner Mani, as she set out from her humble home. We recognized the slim figure of the shrine guardian and supplicant, shortly after we had identified the church from the photographs we had studied in preparation for our trip, as Claire Andreae and I were scouting the area for filming. Holding a cord with a small key in her hand, Metaxia slowly climbed the short hill, pulled one of the branches by the church door to lift herself to the door frame, unlocked the padlock on the church door, and entered the nave to perform her daily candle-lighting ritual at the Byzantine church of Hagioi Theodoroi. With her walking stick as a sturdy companion—«την μαγγουρίτσα μου», as she used to call it—beaming, she explained:

As long as I can walk, I go. I made a vow. Whatever I do, I do on my own. No one asks me. When I light the candle, I leave it lit and the flame goes out on its own.

Metaxia’s humility, warm-hearted presence and quiet spirituality, as she observed her decades-long vow, moved us deeply. We had set out from Los Angeles to film the documentary at the invitation of Professor Sharon Gerstel, a Byzantine Art Historian who had been conducting archaeological research in Mani over the last thirty years, and who sought our help in raising awareness about the state of the church building. We hoped that our film would make a strong case for archaeological intervention and renovation. The project would capitalize on my work on Greek ethnic identity and cultural politics, as it would concern itself with the function of the church as a container of village memory, and explore how the Byzantine past in Mani is featured in narratives of local village identity, through a series of interviews conducted with villagers, members of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lakonia, and members of the transnational Greek American community with strong ties to the village of Vamvaka.

Churches offer a place for venerating divinity and the saints who have long since died, and through the sacraments, they place the community under heavenly rule. For the faithful, churches constitute a concrete living human reality. The church of Hagioi Theodoroi stands at a crossroads, where the road that leads to the mountain meets another that leads to the cemetery. Its position at a boundary point for the village and its dedication to the military saints Hagioi Theodoroi signifies the builders’ intention for the church to provide protection to the village residents. The history of the church has recently been published separately (Gerstel 2020). The documentary Blessings and Vows was completed with grants from Loyola Marymount University (LMU) and UCLA, and my own personal funds, which I utilized to hire Claire Andreae (’16, LMU Film production, Scholar of the Year) as cinematographer, and a talented team of LMU alumni and faculty for post-production. The film has screened in 32 international film festivals, and has garnered six best short documentary awards.2

Since the first encounter with the church and its devout caretaker, I saw Metaxia Anaplioti’s persistent daily practice as an expression of her spirit, that whatever the hardships in life, she has a role to play that transcends the confines of her humble dwelling, and the limits of her own life. During filming and post-production, I had identified Metaxia’s story as a counterpoint to all the other voices in the film, and that is part of the reason I felt compelled to foreground her voice in the film. Withholding my prompts in the film interviews that I conducted, and opting out of a voice-over, I aimed to feature the multiple voices and alternate points of view, as they reflect on the value of the Byzantine church for the community of Vamvaka. The various constituencies represented in the film were: the local villagers (Metaxia Anaplioti, Stamatis Panteleakis, Kyriaki Barbayanni-Panteleaki), the local historian (Mihalis Georgiou Exarhakos) and his wife (Eirene Panteleaki-Exarhakou), the village priest (Fr. Nikolaos Lambrinakos), the Greek American real-estate attorney and diasporic villager (Demetrios Panteleakis), the local archaeologists (Danai Charalambous, Angeliki Mexia). And, though the authorial voice is not pronounced, ultimately all these voices in concert articulate the urgency of renovating the church.

Below: Metaxia places a wax church candle on the standing candelabrum next

to the iconostasis

During our first encounter, Metaxia allowed us to film her during her candle-lighting ritual inside the church. Unfazed by our intrusion, she performed this ritual in the nave of the church. First, she added a drop of water at the bottom of the tabletop vigil lamp, then added oil from a plastic oil container, and then lit the floating wick on the lamp. She, then, took a beeswax church candle and, without her walking stick, walked a few steps to the standing candelabrum by the iconostasis that divides the inner sanctuary from the nave. She made the sign of the cross, and kissed the faded icon of Virgin Mary, which was covered in plastic and affixed on the makeshift iconostasis. She later explained that “it used to be a sturdy church,” adding that “the church had icons, wooden icons, candles, a lot of things. And I would leave it open and they [the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lakonia] asked me to lock it up.”

At the completion of her daily church caretaking, she walked to a low stone fence and sat under the shade of a tree near her home. We conversed as if she were a member of my family. I told her how I came to hear about her quiet life of devotion, and about the state her beloved church was in, how we had plans to tell her story in a documentary aiming to elicit interest in the renovation of the church. I am not sure how much of this mattered to her. I told her of our recent visit at the monastery in nearby Mystras and how I had met the nun Akakia and had confided to her about the ailing heart of my brother-in-law, and how we had prayed for his recovery. In between the words, Metaxia knew the silences. She chose to comment on what I confided to her by tenderly reciting the demotic song “On the dead brother” (Πολίτης 1914, 138–40) with a faint grimaced smile, which I took as a deep acknowledgment of human suffering by someone who has experienced a fair share throughout her life. She prefaced the song as a moiroloi, adding that she knows how to “weep” in the mode of the ritual lamentation songs particular to the Mani region. I was struck by how eagerly she broke into the lamentation song and assumed the position of an actor in the collaborative making of local history. This performance appears through the lens of the young female American-German cinematographer, Claire Andreae, who intuitively captured it without comprehending the content of her utterances. Claire and I exchanged knowing glances, as we both shared the feeling of history in the making, our spirits lifted by the serendipitous performance.

Metaxia’s recitation of the moiroloi forms the preamble to Blessings and Vows, capturing a rare moment of emotional release from our beloved protagonist. The song is adapted from a demotic song, much abridged in Metaxia’s version, who focuses on the suffering of the daughter, Areti, rather than that of the mother who had lost a husband and all nine sons, before dying in the hands of her daughter. I translate below the variant Metaxia recited:

A widow, a noble widow, a proud housewife

that had nine sons and one daughter.

The eight brothers were reluctant to,

but Konstantinos was willing and eager:

“Mother, let’s marry Areti off to a foreigner in far-away lands.”

“And [the mother asked], in the happenstance of a joyous or unfortunate event,

who will bring her back to me?”

“If joy or sadness fall upon you, I will fetch her for you”, he says.

As they leave, Areti departs, along with all nine of her brothers.

And the mother was left all alone and bereft, like the last tree standing.

“The vow you made to me, when will you fulfill it?”, she asks.

So [Konstantinos] asked Hades for permission to go bring her back to his

mother.

[Areti] goes to her mother but the door was closed

and she called her mother:

“Come my dear mother, open up, come, my dear mother.”

And the mother responded:

“If you are a friend, come inside

and if you are an enemy, you should leave

and if you are Death, I do not have any more children to give to you.

I only have my little Areti, but she is far away, in foreign lands.”

And the mother opened up the door and they kissed.

And [then] the mother died.

And only Areti was left.

And she pleaded with God that she may become a bird

and be called Areti and fly around the remote churches.

Now she roams around and she says: “Coocoowow.”

Metaxia’s moiroloi recounts the story of Areti rather than that of Areti’s dead brother, the titular character of the demotic song, whose lines are much curtailed from the traditional longer version. This abridged version leaves out the enchanted narrative of how the birds sing, about how Areti is riding a dead man’s horse, and how the living sister dismounts, and leaves behind the dead brother when they reach the church. In our passage, the enchantment is broken, as Areti goes on her own to knock on her living mother’s door, regaining freedom of movement and exercising her free will, a connection that Metaxia weaves back into her own present—“Whatever I do, I do on my own. No one asks me”—compressing time and space, with a recollection of her own repeated loss, where folklore and family memory converge. Metaxia’s focus is on the story of the last living daughter, with whom she shares an affinity, as both are left behind alone in the village, bereft of a community, but also much like the mother who was “left like the last tree standing,” a connection that conflates mother and daughter through the trauma of loss.

Metaxia narrates the end of the song—“And the mother opened up the door and they kissed. And the mother died. And only Areti was left”—and rounds her story off with a variant that mirrors her own life, reclaiming the story in the mode of a moiroloi, a lamentation of her own suffering. She thus creates her own folkloric configuration of time and space, her own chronotope, making sense of events in her life by creating a story that leads up to them, by beginning from what she currently knows to be true, namely, her daily ritual of roaming around a remote church, having pled to God3 [my emphasis, adapted from the ending in Areti’s moiroloi]. She explains that the church of Hagioi Theodoroi is credited with miracles and provides her own account of the church building by “people who carried the stones on their backs, an old lady told me,” creating imagined continuities to the present, compressing time. Her recourse to a folkloric chronotope is an act of reclaiming power to determine what is real, taking authority over her own personal narrative, her own story. She concludes with: “That’s it. Do not think badly of me” [«μη με παρεξηγήσετε»].

Suffering is central to the lamentation songs of Mani, not only as an object of representation, but also as a means of establishing personal storytelling and history as both real and true. During the second day of our visit, we filmed an interview in Metaxia’s home, a single room with a narrow bed with faded cushions, a two-plate portable gas cook-top, a heater, some hooks to hang her clothes, and a shelf with family photos. She pointed to one of the photos and said: “That is my nephew who passed a year ago; he left a year ago, he was 62 years old; a dentist; he was like my brother; he was my sister’s son.” Metaxia helped raise her nephew, Stavros Bathrellos (1950-2016), who lived with his father in a neighboring village, when her sister was hospitalized in Athens for long periods in the 1950s. As a result, she was very close to Stavros, and was devastated by his untimely death. He is the nephew she spoke to me in private and pointed to his picture framed and placed on the shelf, near the makeshift icon-stand, once again using a grammar that conflates past and present. Her face assumed the same grimaced smile I had noticed when she recited the lamentation demotic song the previous day, during our emotionally charged moment of the first chance encounter.

Leaning forward, she began narrating her personal story performed for her attentive audience in the room, captured in our film:

Εδώ που με βλέπεις, έχω περάσει πολλά.—Here where you see me, I’ve been through a lot. Because we were poor. My mother left me when I was 5 years-old. So, I took care of my father. And, I took care of my sister; she was older and I stayed with the one who got sick and I took care of her and then she died. And then I took care of my father. And I had livestock and was working so we could earn a living. We had nothing before. We just received a small pension for farmers [αγροτικούλα], 300 Euros. I pay the electricity bill, the telephone bill, and I pay for everything with just this small pension, as you see me. I was making ends meet [οικονομολόγα] because I’ve lived the life of the poor.

Metaxia has resigned herself to “the life of the poor,” her narrative punctuated by stations of suffering. Her father was Petros Anapliotis. His second wife was Stamata Diasakou, Metaxia’s mother. Their first daughter was Eftychia (1926-2004). The second daughter was Miliá, who was born in 1931 and probably by around fifteen years old or younger began having the first symptoms of multiple sclerosis. During the last years of her life, she was paralyzed. After the wedding of the older daughter Eftychia in 1948/9, Metaxia became the caretaker for Miliá, who passed in the mid 1950s (circa 1954). The son, Nikos, was born probably in 1932 and died on May 15, 2020. The last daughter was Metaxia who was born probably in 1938. Metaxia’s mother probably died in 1942. Her father was born in 1869 and died in 1976, at the age of 107 years old. Metaxia took care of her father from the late 1940s (circa 1948), when her older sister married, until his death.

I asked her how many candles she had lit so far, and she replied with the rationale for her vow:

[For] many years… I lit a candle in the morning, winter and summer. I love the church, and I said I would light the candle… since I was hit by a car in Athens, I told him [i.e., to St. Theodore], since He healed me, “I’ll come and light your candle.” I crossed the road and was hit by a car. I was 30 years old. I went to the hospital and stayed in for a month. That nephew I was telling you put me there. When I became better, I made a vow. And I came here with my walking stick, slowly, slowly. And, then I became better and was picking up the olives, and took care of the livestock. As long as I walk, I go. I cover the cost. I made a vow. I buy the oil, because I cannot pick up the olives now.

After her father’s death in 1976, Metaxia visited first her brother in Thessaloniki for a short while, and then her sister in Athens, who was living with her son, Stavros Bathrellos, and his wife, on Marathonos Avenue, at Stavrós, in the suburb of Aghia Paraskevi. There, in the summer of 1977, while crossing Marathonos Avenue, Metaxia was hit by a car, when she was about 40 years old, not as she stated, in her 30s. She stayed away from the village for about two years. Her leg never fully recovered from the accident, but she was strong enough to live independently.4

Metaxia rekindled her vow daily, not only to express her gratitude for her miraculous survival from the car accident, but also because she saw the church as a living being in need of her own care. The magnificence of her simple life and graceful humility was reassuring and alluring to me. I felt the affinity I had towards my beloved maternal grandmother: “Now you are a grandmother to all of us. You take care of St. Theodore,” I interjected, and continued: “Why do you love the church so much?” She replied, as if stating the obvious: “If my sister was here, she’d tell you. I love [the church] because there is Christ and God. And I do not want anything else.” She continues with a story that is offered as evidence of the lengths of her commitment to her vow:

[One day] it was raining a lot and I did not manage to go to the church and light a candle. And, I lit one at home, and I said “St. Theodore, take from here [the candle-light], if you want to see… since I was not able to go [to the church].” What could I do? I slept and I had this all night in my mind. In the morning I went again.

The temporality of enchantment does not frighten Metaxia, who addresses St. Theodore directly on a rainy night when she could not venture to the church to light a candle. She invites him to share the light from her candle at home. Her vow to St. Theodore is not a simple promise; it constitutes a reciprocal relationship to the Saint she invokes in her prayers. Metaxia gains agency as she invokes the divine, as a way of resolving the predicament, by reaching outside of time and space, and thus, leveling the multi-spatiality of the church and the division between the human and the divine realm (see Lambek 1998).

Metaxia’s care for Hagioi Theodoroi focuses on the loss of communion and service for the faithful during the time of disrepair:

Now you see the church… it needs to be repaired. It needs its books. You can’t leave it like this. There was a tree that had branches come out of the roof. It would have caused the church to collapse. To rebuild this church, it would take a lot. It would be good for all. Now, on Sunday, we could bring a priest and have a liturgy; and at Easter, we could have liturgy. And, now, if someone dies, the priest comes and reads him [i.e., reads a prayer; conducts funeral ritual], and if there is a baptism, he baptizes. I remember we’d decorate the Epitaphios and we processed to the cemetery and brought it back to the church… it used to be sturdy church. It used to have columns… it was an ancient church, before Christ, ancient.

Metaxia wishes for the church to be rebuilt, so that there will again be a communion between the divine and the personal within the “ancient” sacred space, shared between the people of the local community. She reminisces about a time the church was “sturdy,” in a distant past, with its columns, “before Christ, ancient.” The temporalities are again conjoined here, later generations do not displace the earlier ones. The religious and folkloric chronotopes coincide as Metaxia creates her personal identity through the subjective continuities of memory, regional historiographies, and legends. Her church is a communal space, and without its people and the liturgies, it stands alone on a Sunday and during Easter. Joanna Eleftheriou’s childhood memory captures the feeling of a church without its community: “I think about the black-wicked candles by the icon of the Virgin Mary, who is alone this Sunday. The black-wicked candles by the icon of Virgin Mary are without flame, and our Lady will be gazing out at no one” (2020, 30).

I tell Metaxia that when I went to Mystras and saw the nun, Sister Akakia, I explained to her that we would be going to Vamvaka to film the church and raise awareness and funds to restore it, to which Sister Akakia responded that the road will open up, so this project will come to fruition. To this, Metaxia replied: “I don’t know if the path will open… if people are interested, then maybe the path will open… the church needs care… and then the road will open.” Our feeling of intrusion, on the first day of filming Metaxia while she performed her most intimate act of devotion—the candle-lighting and prayer—was transferring a separation between public and private that was foreign to her. Metaxia wished the world to bear witness to the state of the church, care in communion with her, so that the path towards the renovation of the church and the restitution of the communal sacred space would come to fruition.

After an hour-long interview, Metaxia returns to the repertory of her natal land and recites a local demotic song about regional pride.5 And then she elaborates on the pride Maniotes take in their long history of resisting foreign invasion:

Many Maniates are proud. They say my fatherland is Mani. And it is true. Mani used to have so many people. Towers. But now, it’s desolate. Because women were working, they were doing what they wanted. They were manly women. I was young. But Mani is Mani. I love Mani.

She was that woman who worked the land, cared for her family, and for her church. Her purpose was clear—Mani is her place of belonging, and she intends to remain steadfast, a towering presence in a desolate landscape.

I asked her how she felt that so many of us have come from the American Universities and care about the church? “I like it. I’d like to see the church repaired. I love the church. And I said that I will light the candle. What you do, for example, is your decision. If you’d like to bring a bottle of olive oil, bring it, I will not stand in your way. What you’ll do is your own story. You have my blessing and god’s blessing. We celebrate the Virgin Mary… My child, I don’t know. What can I say. Tell you lies? Thank you. And forgive me that I am not proper.”

Remaining in her natal land, in the house where she was born, and caring for her sick sister and centenarian father, she reclaims the agency to choose the place where she will die and the land where she will be buried. She asserted to me privately on the last day I visited her that though the winter is cold, and she feels alone and isolated, she would never leave her Mani. Before leaving, she took me to her vegetable garden, and offered me flowers, herbs and vegetables to take the taste of Mani with me, a part of her land to hold me together in the far away land that Areti was taken away. I promised to visit her again when I return to Greece. I did not make it on time. On February 13, 2018, Metaxia’s humble home burst into flames and consumed her body with all her favorite belongings, a sepulcher of her own making. Leaving this world so imperceptibly, exhaling into the light, her ethereal being vanishing into the bright air.

I could not have anticipated that the paradox of the simple but purposeful life of Metaxia Anaplioti, and the flickering of some fifteen thousand candles that she lit while upholding her 40-year vow, would lift me up and light my path in the intervening years since her passing, as she became a posthumous spiritual guide for me, strengthening my resolve to continue working with an open heart, discovering my voice, as I, in turn, uncovered the stories of others whose voice was muffled or stifled by larger agendas.6

This first film of mine bears the traces of serendipitous, or even magical, encounters. First, I received the blessings of sister Akakia, an Orthodox Christian nun at the monastery of Pantanassa in the medieval ruins of Byzantine Mystras. Then, the Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia granted permission to film inside the church. When we arrived at the village we were greeted with the warm hospitality of the locals at every step of our journey. The village commissioner, Stamatis Panteleakis, and his wife, Kyriaki Barbayanni-Panteleaki, opened their restaurant for us. The priest of the village, Fr. Nikolaos Lambrinakos, offered the first memorial service in over 70 years in the church. While officiating, he acknowledged a thousand-year lineage to the first priest and his wife, the builders of Hagioi Theodoroi. A Greek American lawyer from Massachusetts who is a proud descendant of Mani, Mr. Demetrios Panteleakis and his wife Erin, opened his home for us. When we asked his aunt, Koula Panagiotopoulou, to compose a moiroloi to remember Metaxia’s devotion, we began drafting it together during film production in her home, it was further developed by Panayiotis Katsafados, and it is now featured in the end titles of the film. And another serendipity to lift our hearts—Metaxia’s great nephew, young Kyriakos, son of Theodoros Anapliotis, and the last descendant of the Anapliotis’s family that hails from Vamvaka, was baptized outside of the church of Hagioi Theodoroi on our last day of filming, on July 1, 2017. We learned from Kyriakos’ godfather, Demetrios Anapliotis, that, “Kyriakos is named after the earliest recorded descendant of the family (1668), and his grandfather’s brother missing in action during WWI, was also Kyriakos.” Our journey began with the vow Metaxia Anaplioti took to light a candle daily at the church of Hagioi Theodoroi since her car accident 1977, and ended with the vow her nephew, Theodoros Anapliotis, took to baptize his third son at the of the same church for its proximity to his father’s tomb at the nearby cemetery. The church had been used 70 years ago for burial services, and circa 100 years ago since the last baptism was performed there. Metaxia did not live to witness the next service inside a renovated church of Hagioi Theodoroi, but perhaps the young Kyriakos Anapliotis will live to celebrate his wedding there.

At the end of the interview, Metaxia, curious about the capturing of her image and voice in the camera: “Now, [this microphone] has it taken my voice? What did it do?”

When Demetrios Anapliotis, Kyriakos’ godfather, saw the film, he called it “magical,” for recording the beauty of such a soul: “When Christmas Eve comes, how we wish for a miracle! And miracles really do happen. And such a miracle for my family was your film for our beloved Metaxia. We saw her again during Christmas Holy night… God bless you!”

Both the villagers of Vamvaka and I have also experienced losses, the untimely passing of my brother-in-law, Dimitris Tsalkitzis (1964-2018), on January 9, 2018, five weeks before Metaxia’s sudden passing on February 13, 2018. And, Stamatis Panteleakis, the village commissioner, who was so generous with his hospitality at his restaurant during the film production, and had shared how he used to ring the church bell as a child, and had reached out to the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lakonia to petition the state to renovate the church of Hagioi Theodoroi, and was so “truly moved” with our efforts to publicize the state of the church—“this small church is our life here”—is no longer with us. He passed, after a short illness, on January 30, 2021. May the renovation project for the church come to fruition and may his memory be eternal.

I am grateful for our encounter, dear Metaxia, for your life of purpose, true to your vow, at a time when all relationships seem so trivial and fleeting.

In the closing frame of the film, following her daily ritual of candle-lighting, the edges of Metaxia’s body begin to dissolve as she steps out of the church, suffused in the brilliant light of the sun. We witness her transient image, as she holds on to the frame of the door, to get support to climb down the step and lock the church door behind her, before she vanishes into the light. The luminosity is powerful, a vivid reminder of Matthew 5:16 “You are the light of the world. So let your light shine before you, brothers and sisters, in this world that they may see your good works and give glory to the heavenly Father.”

The film is dedicated to Metaxia Anaplioti’s strength of conviction and to her eternal memory.

Katerina Zacharia

(M.A. and Ph.D., University College London) is a Professor of Classics at

Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research explores Greek

ethnic identity formation, Greek tourism, and cultural politics. She is an

experienced dramaturge, narrative design consultant, with an expertise on

creative adaptations of classical antiquity in visual culture. A long-term

collaborator and producing-partner with the Stanford Repertory Theatre, she

serves as Artistic Associate for the Michael Cacoyannis Foundation in

Athens, and Director of University Connections for the Los Angeles Greek

film festival. She has collaborated on the writing of documentaries,

fiction, and VR games, and is currently working on an interactive media

game drawing on classical drama.

*A Triptych of Essays about Blessings and Vows:

After the completion of the film, I invited two scholars—UCLA

anthropologist Professor Laurie Hart, and Ohio State University

transnational studies Professor Yiorgos Anagnostou—to reflect on the

folkloric, cultural, and diasporic discourses at play in Blessings and Vows. The purpose was to explore ideas of

temporality, religiosity, representation, personal and village identity, as

well as issues pertaining to cultural heritage preservation in contemporary

Greece from an anthropological and cultural studies perspective. The two

papers were presented at the 26th Modern Greek Studies Symposium in

Sacramento, on November 7-10, 2019, in the panel “Cultural Heritage

Discourses in a Greek Rural Village.” My essay complements the film and the

two essays in the triptych published in Erγon on

the same day as the official release of Blessings and Vows.

For Laurie Kain Hart’s essay “The Uses of Abandonment: Reflections on the

Film Blessings and Vows” see here. For Yiorgos

Anagnostou’s essay “Voice and Voicing in Blessings and Vows:

'Finding' and Funding Heritage in the Greek Transnational Village” see here.

Notes

1. Blessings and Vows 2018, Athenoe productions. Short documentary (15 mins). Producer, Writer, Director: Katerina Zacharia. Executive Producer: Sharon Gerstel. Assistant Director, Cinematographer, Editor: Claire M. Andreae. Music Composer: Mladen Milicevic. Color Correction: Huan Manton. Sound Mixing: Brandon Cudequest. Post-Production Assistant: Kelly Sarri. The documentary was filmed during the week of June 24-July 1, 2017. The copyright of the depicted antiquities belongs to the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports. N. 3028/2002.

2. For updates on awards and film festival screenings, go to: https://www.athenoe.com/blessingsandvows.

3. Bakhtin (1981). For a useful analysis of the “The Chronotope of Enchantment,” see Camilla Asplund Ingemark (2006).

4. My thanks to Eftychia Bathrellou for confirming the biographical details for her aunt, Metaxia Anaplioti, and for her hospitality and friendship.

5. Metaxia recited a demotic song, popular in the region of Mani: «Η πατρίς μου είναι η Μάνη, που κανόνι δεν την πιάνει. Που’χει πύργους υψηλούς, και λεβέντες διαλεχτούς. Πως γυναίκες λεοντάρια, πολεμούν με τα δρεπάνια. Τούρκοι, Τούρκοι δεν ντρεπώστε, Με γυναίκες να μαλώστε».

6. Eternal gratitude to Edward McGlynn Gaffney for stirring my spirit into the light, and representing my interests, fairly and firmly, when adversity rocked my world after the production of the film.

Works Cited

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson & Michael Holquist, University of Texas Press.

Blessings and Vows. 2018. Written, directed, and produced by Katerina Zacharia. Athenoe Productions.

Gerstel 2020. “Recording Village History: The Church of Hagioi Theodoroi, Vamvaka, Mani.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 38 (1): 21–41.

Eleftheriou, Joanna. 2020. This Way Back. West Virginia University Press.

Ingemark, Camilla Asplund. 2006. “The Chronotope of Enchantment.” Journal of Folklore Research 43 (1): 1–30.

Lambek, Michael. 1998. “The Sakalava Poiesis of History.” American Ethnologist 25: 106–27.

Πολίτης, Νικόλαος Γ., Εκλογαί από τα τραγούδια του ελληνικού λαού. Λαογραφική Βιβλιοθήκη του Κέντρου Ερεύνης της Ελληνικής Λαογραφίας. 1914. Available online by the Academy of Athens .